Łaźnia Centre for Contemporary Art, Gdańsk

13 December 2018 — 17 February 2019

by JOE LLOYD

On the surface of it, the British art historian Nick Wadley – who died in November 2017, aged 82 – was a paradigm of the successful, respected academic. Born in Elstree, Hertfordshire in 1935, Wadley studied fine art at Croydon and Kingston Schools of Art and history of art at the Courtauld Institute in London. In 1962, he took up a teaching post at Chelsea College of Art, where eight years later he was appointed head of art history. At Chelsea, he established himself as a leading specialist on post-impressionist and modern art in France, publishing books on Van Gogh, cubism and Cézanne. After early retirement in 1985, he produced Noa Noa: Gaugin’s Tahiti (1985), a definitive critical edition of Gauguin’s travelogue, and what is still the standard study in the English language, Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Drawing (1991). He also curated exhibitions – on Kurt Schwitters, Lyonel Feininger, Franciszka Themerson, Roman Cieślewicz, among others – gave lectures and contributed to journals, catalogues and the Times Literary Supplement. It was, to put it mildly, a prolific output.

[image10]

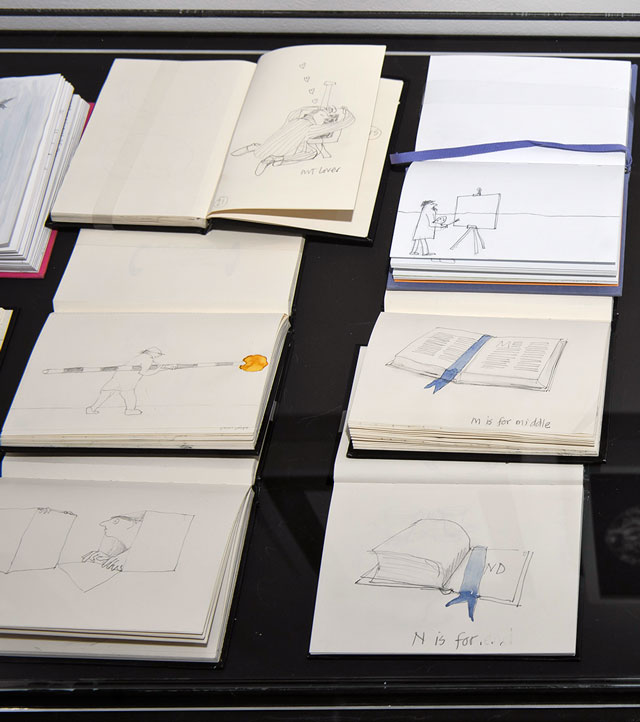

Yet Wadley’s scholarly career was only one side of his work, for he was also an artist and illustrator. His chosen medium was drawing, and, especially in his last three decades, he drew incessantly. There were cartoons, with his friend Sylvia Libedinsky, for the Daily Telegraph, and illustrations for books by Robert Walser, Lisa Jardine and others. Most recently, he produced a series of volumes, many for the avant garde publisher Dalkey Archive; the latest, Man + Table, appeared in 2016, with several more completed before he died. “There was always paper,” says Wadley’s widow, the curator Jasia Reichardt. “In his pocket, always a small drawing book, pen, pencil and a rubber. Under his pillow, a drawing pad and a pen.”

[image9]

It is thus fitting that visitors to the opening of Nick Wadley in Gdańsk – a survey of, and a tribute to, Wadley, held at the Nowy Port branch of Gdańsk’s Łaźnia Centre for Contemporary Arts – were gifted with a sketch pad. Curated by Reichardt, the exhibition amply demonstrates the joy Wadley found in drawing. It is also unrelentingly hilarious, letting fly gag after gag like a fleet of well-aimed paper planes.

[image3]

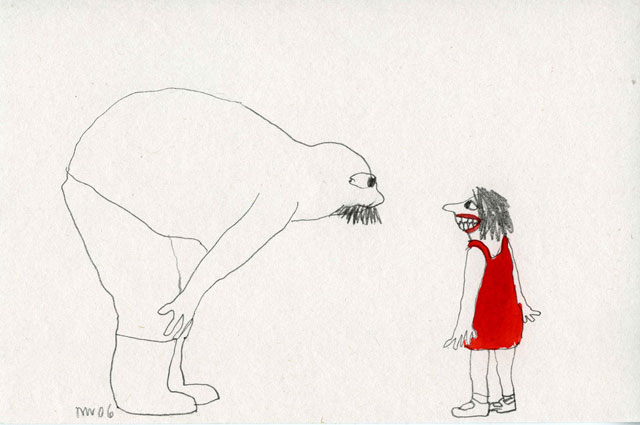

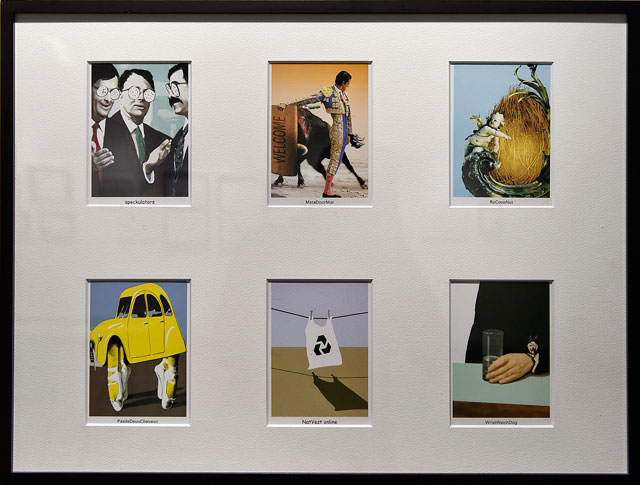

Wadley was fixated by wordplay, and many of his drawings stem from puns, the elisions between morphologically proximate words and outré interpretations of well-known or idiomatic phrases. In A Life in the Day, for instance, a fly drops dead after convolutedly crisscrossing a window. Private View has a waggish man holding up a frame to glance at the titular event’s prosecco-swigging attendees, while The Artist as a Young Man shows a caveman painting on his wall. There are some welcome moments of puerility. Le Chien and the Loo, a play on the title of Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dali’s unforgettable surrealist short Un Chien Andalou, depicts exactly what it sounds as if it should. A particular punning set of six of his Daily Telegraph cartoons includes such pleasing compounds as RoCocoNut and MataDoorMat. “How,” says Reichardt, “do we look at the world? We can look from above, or we can look from below. Nick used to look at it from the side.”

[image4]

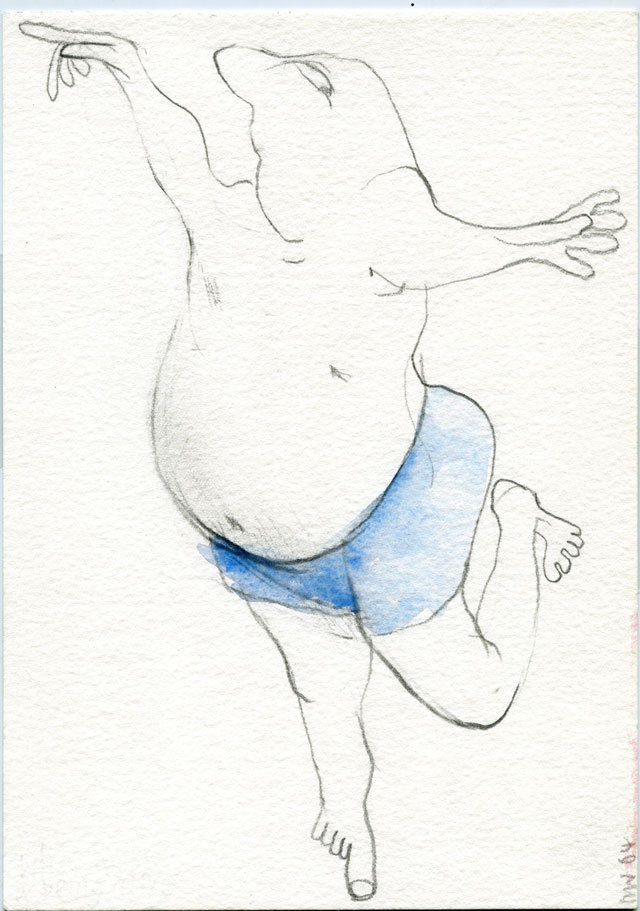

If one contemporary artist comes to mind when surveilling Wadley’s drawings, it would inevitably be David Shrigley, especially given that both happily embrace the postcard as a vehicle for illustration. But Wadley is wrier, with a tauter interest in movement and the human form: Big Man Dancing glories in the contortions of an obese man’s unexpectedly light-footed dance, while Footballet has a footballer pirouette, twirl and flip.

[image2]

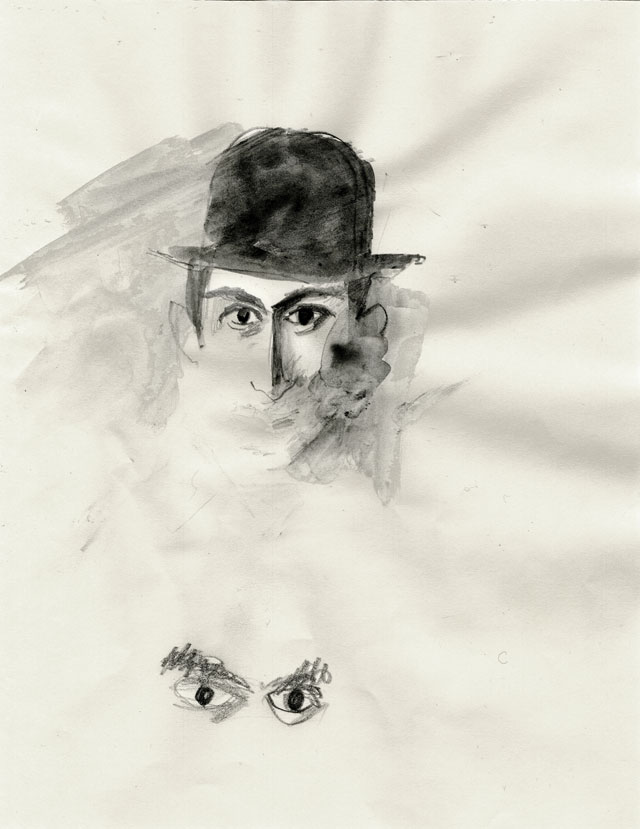

Wadley was also, as one might expect given his academic career, steeped in artistic and literary history, and Nick in Gdańsk demonstrates a fascination with modernist’s more absurd manifestations. A bookcase of curiosities includes such items as a giant screw inside a box labelled Tower of Babel, an eyeball in a sherry glass and a set of snail shells bursting out of a sardine tin. One of the first pieces in the exhibition, Beckett Play, reduces Waiting for Godot and Endgame into a three-panel cartoon; another section focuses on drawings inspired by Kafka, including an unnamed image of three large-membered anthropomorphic hounds, howling like dogs. And there is a watercolour sequence depicting characters from Alfred Jarry’s wilfully vulgar symbolist play Ubu Roi (1896); such was Wadley’s engagement with Jarry that, in 2001, he was elected to the Collège de ’Pataphysique, the society founded in Jarry’s memory, whose members have included numerous surrealists and wordplay-obsessed Oulipo writers.

[image5]

In spite of these literary affinities, however, some of Wadley’s most affecting work was taken more directly from experience. He would draw, according to Reichardt, “on trains, at lectures, in the street and often in waiting rooms”, and even from television programmes, which he would use to practise the rapid catching of movement. A series of drawings inspired by Wadley’s stays in hospital, which were collected in the book Man + Doctor, are at once clownish and moving. One, dubbed Through a Glass Darkly after the Biblical phrase (and the 1961 Ingmar Bergman film), shows a bedbound figure recoil in horror at a bottle of water; whether it is because of the bottle itself, something glimpsed through it, or the figure’s own reflection remains ambiguous. Another in the same set shows a man in a waiting room, cheerlessly decorated with a sign reading “WAIT”, while two staff peer, possibly mockingly, from behind a door, while a third shows a patient lying anxiously as a triad of doctors appear to connive sinisterly. Fleeting instances are expanded into stories.

[image6]

There is something in these again of Kafka, with his sinister institutions full of elusive codes. They also present parallels with the bleakly comic oeuvre of the Swedish filmmaker Roy Andersson. Working in advertising for several decades after the failure of his second film, Andersson honed an ability to compress all life’s absurdities into sequences of spare, ironic vignettes. Wadley’s best drawings, themselves often minuscule and confined to a single moment, achieve something similar. “The paper he worked on was small,” says Reichardt, “but the themes he worked on were enormous.”