Moco, Barcelona

On permanent exhibition from 16 October 2021

by ANA BEATRIZ DUARTE

Visitors to the Modern Contemporary (Moco) Museum in Barcelona will probably not view NFT: The New FuTure as an exhibition in itself, but as just another permanent section of the newly opened branch of the private museum inaugurated in Amsterdam in 2016. The small room in which it takes place hosts six non-fungible tokens (NFTs, also known as nifties), unique digital pieces of art traded using blockchain technology, which gain physical existence by means of TV screens. All the pieces belong to the same collector, identified as “33”.

NFTs are tokens that link a digital object or artwork using blockchain technology, a decentralised way of making payments with cryptocurrency, in order to make them unique and thus guarantee ownership. They were first used in 2017, when the so-called CryptoKitties debuted as tradable collectibles via the Ethereum GitHub.

In contrast with the artists displayed on Moco’s first floor, assembled under the title Moco’s Masters and including names such as Salvador Dalí, Andy Warhol and Banksy, the names on the tags here – although they are some of the most sought-after artists producing NFTs – are not likely to be recognised by most visitors. An exception is Paris Hilton, a celebrity who partnered with the American digital artist Blake Kathryn to enter the new digital art world.

Hilton, who defines herself as an “OG Crypto Queen” (OG standing for “original gangster”), is an enthusiast of the NFT world, having ranked seventh on Fortune’s 2021 list of top NFT influencers. “Imagine buying an NFT for a dress you can wear in Fortnite or on your Roblox character,” she says on her website.

[image2]

Bedroom Bliss (2021), delivered as an open edition, is a part of a collection named Planet Paris, created in partnership with Kathryn, whose dreamy and colourful landscapes are meant to work as a therapeutic strategy to escape from the stresses of the real world. Hilton, describes Bedroom Bliss as an “ethereal escape … a heavenly sanctuary for the life I would build”. The piece displays her bedroom in the metaverse, with a sparkling bed, a chandelier and dog statues over an altar of sorts, reachable by a swimming pool staircase through a garden, all in a misty atmosphere that makes it feel as if it is floating. Everything is pink, even the sky spinning around the “sanctuary”.

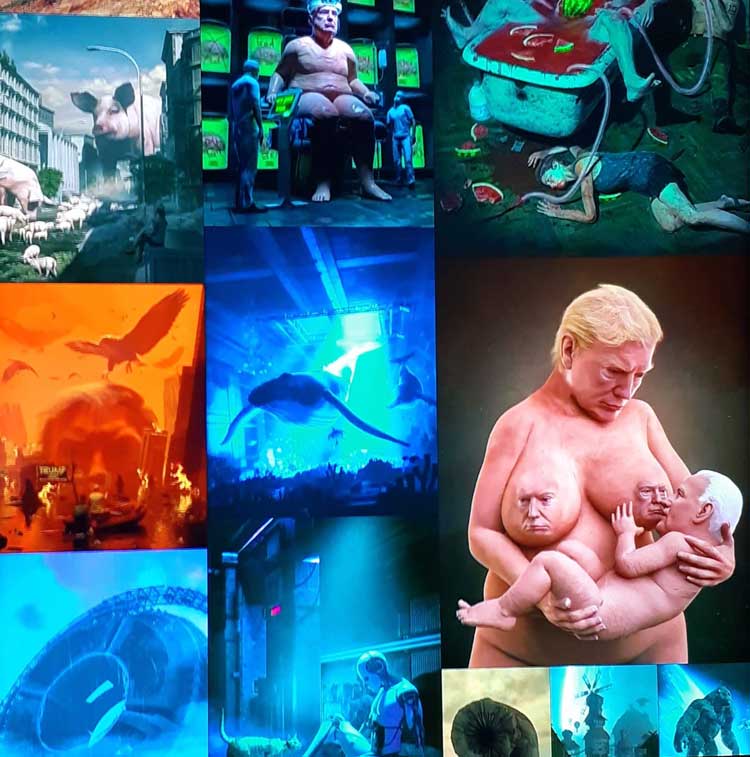

The other names in Moco’s exhibition are also superstars within this new universe. Beeple (real name Mike Winkelmann), for example, is No 1 on Fortune’s list. The young American artist shot to world fame in 2021 when Christie’s sold one of his digital works, Everydays – The First 5,000 Days, for more than $69m, making it the most valuable NFT ever. It was also the third-highest auction price achieved for a living artist, after Jeff Koons and David Hockney.

[image3]

Everydays – Raw (2020), his piece at Moco, is a reduced and earlier version of the record-value piece, in a limited edition of 100 (just like engravings), displayed as a four-minute video in which a composition of Everydays’ drawings in different sizes scroll down. The name derives from the fact that Beeple, whose pseudonym comes from the name of an interactive stuffed toy from the 1980s, has been creating one image a day for about 14 years. The piece is a parade of robots, monsters and other weird creatures mixed up with pop culture figures such as Pikachu and world leaders, such as the former US president Donald Trump and the North Korea leader Kim Jong-un. While some may find the 3D apocalyptic scenes created with stock images as a humorous political commentary on contemporary issues, some critics have called them exhausting and even puerile. Oddly, the artist seems to agree, as he states on his website that “a lot of it kind of blows ass” and that “he’s working on making it suck less everyday”.

[image5]

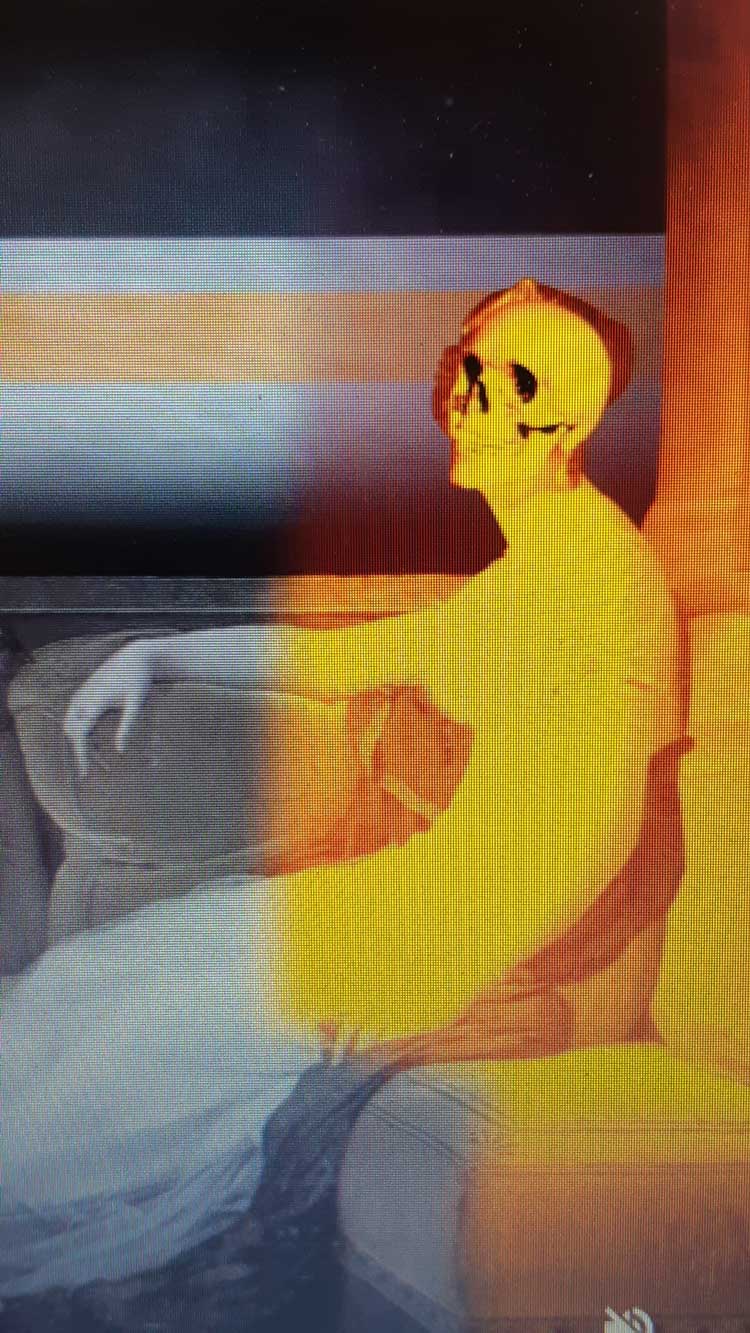

Another American, Daniel Arsham, is less controversial, perhaps because he comes from the traditional art world. Traditional, though, is not the best word to describe his work, which dissolves – erodes, even – art’s internal limits, merging sculpture, architecture, drawing and video art. His style is no easier to define. In Eroding and Reforming Bust of Rome (One Year) (2021), the piece at NFT: the New Future, one can find traces of surrealism, hyperrealism and classicism (as he revisits the art from the Roman Empire) all mixed up with archaeological research that he says is fictional.

The work is his first NFT, but it is also a suite of previous creations exploring classic sculptures in ruins, where time was already a central topic. It displays a replica of a Roman bust from the Louvre Museum, which was part of his latest exhibition in New York, in 2021, at the centre of a courtyard surrounded by a garden. As time passes, symbolised by characteristic signs of the change of the seasons, such as flowers in spring and leaf fall in autumn), the sculpture erupts and, after a complete cycle of one year in real-time, falls from the pedestal. The decay is observable as the “camera” moves around the piece, showing eroded plaster where coloured crystals arise. After the course of a year, the cycle restarts, continuing over and over, for a thousand years. Or, as the artist has said, “for as long as the internet exists”. The video on display at Moco Barcelona is, of course, an extract from the year-long one.

[image4]

For an artist pretty much devoted to materiality, the piece could seem a fresh start. But the impression dissolves when we notice the continuity of the confrontation between far past and far future, as well as between time and space, as in his previous work – apart from his characteristic almost-monochromes. Moreover, the piece provides the same push of boundaries, this time inside the new medium of an NFT: an artwork that modifies over time. Arsham enlisted the help of studio Six N. Five and the Nifty Gateway platform to bring the idea to reality.

[image6]

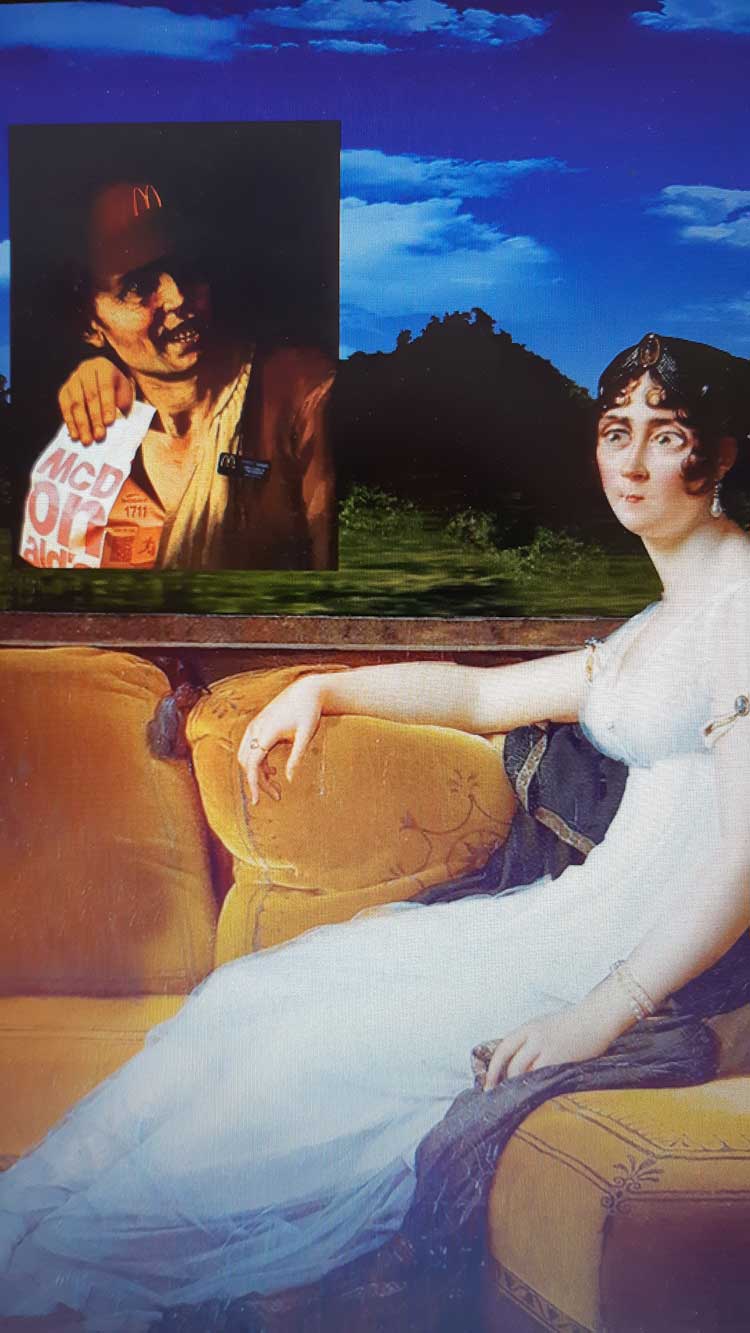

Alotta Money, whose official webpage shows it raining money, is a French crypto artist who describes himself as a “Photoshop Priest”, an “NFT Machine” and “Most Humble Visual Orgasm Provider in the Space”. The pseudonym reveals his humorous approach – often with political messaging. “I’m on a mission to take you to silly places, drop some silly seeds in your pockets and hope you’ll water them,” he says in an interview published on the website Artynft. His Time Fries (2020), at Moco Barcelona, is an after-effects animation after the painting Madame Bonaparte at Malmaison by François Gérard. The couch on which the noble lady sits in the original piece has become the seat of a means of transportation she conducts. Moving her arms as if shifting gears, she makes the carriage move. At a stop, a boy, another modified painting, drops in a McDonald’s bag, while the lady makes a funny face raising her eyes. Then, as if she is passing through a tunnel, an X-ray-like illumination reveals her skull. Finally, when she shifts gears again, a basketball rolls in next to her. And the cycle restarts.

[image7]

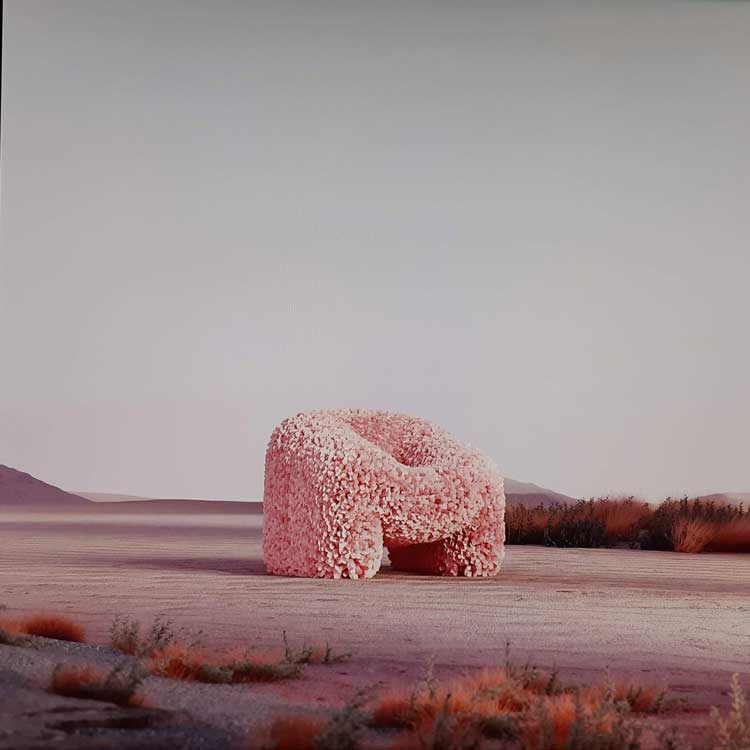

The final artist on display, the Argentinian Andrés Reisinger, has two artworks at the exhibition. One is Hortensia Chair (2021) (hortensia is Spanish for hydrangea), a pink fluffy armchair made of fluttering petals located in the middle of a deserted landscape, which Paris Hilton would probably love in her bedroom in the metaverse. Created in 2018, it soon went viral on Instagram, and was then turned into an object with a physical existence. Last year, the original computer-generated image was also minted as an NFT.

[image8]

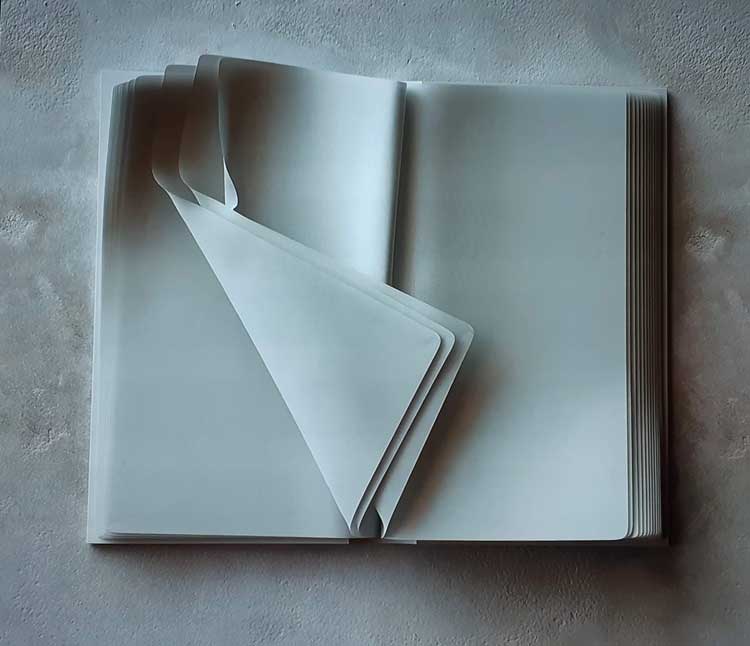

Reisinger once said that he tries to “evoke sensations that … connect one to their memories of the physical experience”. An Essay Before Meeting My Daughter (2021), on the other hand, is not sensorial, but oneiric. According to the artist, it expresses his feelings while expecting the birth of his daughter. It is a two-minute sequence, with music by Daniel Alvarez, in which apples pop up from mountains, a translucent giant cornet flies over a snowy land and the pages of blank books are turned over, still to be written. “If it’s too weird, it’s instantly dismissed; if it’s not strange enough, it is absorbed into everyday reality,” Reisinger said of his work during an interview with the design studio Octaevo.

[image9]

While gathering some interesting works that have traded as NFTs, the exhibition at Moco fails to account for the new field. NFTs are not really a style, nor are they an innovation in art creation, but they are new in terms of the art market. Besides, The New Future also fails to accomplish Moco’s owners’ stated goal of “enlightening” its audience. No information – apart from a poor, unclear introductory paragraph – is provided, something also true for the rest of the museum, with confusing tags and a lack of institutional materials.

[image10]

Unfortunately, it fails to grasp the opportunity to raise many interesting aspects of NFTs, such as the controversies around the blockchain carbon footprint, recent cases of fraud, or the paradox between unique ownership and infinite reproducibility. Neither does it consider the positive that NFTs make it possible for artists to monetise digital artworks and be entitled to royalties each time the work is resold. There is nothing to arrest viewers, to stop them going without pause from one Instagrammable room to the next: they can simply stop for a moment in front of one of those funny meme-like images, before moving swiftly on to the next, leaving the exhibition with no further knowledge, thrill, or “inspiration” about NFTs than they had when they entered.

Finally, the exhibition, whose curators are not named, dramatically fails to represent NFT creation. Or it doesn’t even try. The small number of representatives and the fact that all six pieces belong to the same collector may be one reason. Most of the artists are young white men from the US or Europe. Even Reisinger is based in Europe. What is more, the artist has declared that “the human body is the foundation for the colour palettes of my work”, clearly ignoring that not all human bodies are pink, like his aseptic landscapes and pieces of furniture.

Moco’s slogan is “In art we trust”. It seems that it is doing just that and failing to act as an intermediary or educative institution.