10 November–20 December 2009

A Foundation, Rochelle School, London

by JAMES WILKES

This year’s selectors were Ellen Gallagher, Saskia Olde Wolbers, John Stezaker, and Wolfgang Tillmans, and an extract of their conversations during the selection process, published as a transcript in the exhibition catalogue, shows the thought they have put in to the process of choosing each piece, as well as highlighting their role in shaping its presentation in the gallery. This is particularly evident in their debates over photography and video works, the dimensions of which can be re-determined each time they are shown. As Sacha Craddock, the Chair of New Contemporaries, writes, their job is to “best convey what the selectors understand an artist wants to say”.1 It is this aspect of the selection process that makes New Contemporaries feel a bit less like a machine for gathering new talent to feed the market, and more like an extension of the supporting and shaping hand of the art school.

The biographies of a number of these artists reveal that they have featured in previous New Contemporaries shows, and as in previous years, the selected work is by and large very accomplished. A wide range of practices are in evidence, from printmaking and collage to video art and sculpture, although live art and conceptual works are thin on the ground. Whether this is due to the preferences of the selectors or a lack of submissions is hard to tell. It may also simply reflect the deliberately oblique relationship such disciplines have with gallery spaces and the selection process.

There are a number of artists’ films in the show, ranging from the hyper-saturated tartan surrealism of Rachel Maclean’s Tae Think Again (2008), to the quietly powerful political engagement of Alexandra Handal’s From the Bed and Breakfast Notebooks (2007–8). Dean Kissick meanwhile, drawing on an MA in Curating Contemporary Art, cuts together art historical images into a dizzying collage, the images presented at such speed that they flicker on the border of recognition.

Other artists continue to mine a documentary vein, including Amanda Wasielewski, whose Supervision: Wamina, MN (2008) records the final messages of phone hackers and analogue aficionados over the last analogue telephone system in the US, just prior to its decommissioning. Their farewells form the soundtrack to a film of the landscape of rural Maine, appropriately shot on another classic medium of the pre-digital age, a Super 8 camera.

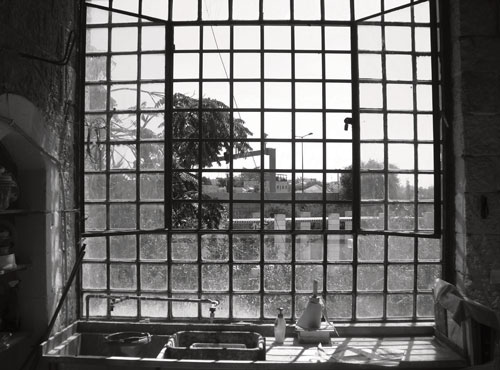

Meanwhile, certain works appear to partake of the documentary tradition, whilst complicating some of its assumptions. Teresa Eng’s series of photographs Conditions for Living (2008) are sombre, dignified portraits of refugees living in temporary camps in Northern France, and according to the catalogue transcript, provoked debate amongst the selectors. Their discussion, in which John Stezaker argues for the photographs precisely because they go beyond the “condescension of the documentary”,2 also reveals that the artist intended to show her portraits alongside photographs of her subjects’ living conditions. The selectors have evidently decided that the portraits are stronger if they stand alone, and they are probably correct, but the discussion shows the editorial and curatorial influence that has been brought to bear on this exhibition.

It is interesting to consider the political and ethical implications of this series besides another group of ambiguously documentary photographs, Simone Koch’s But We Must Cultivate Our Garden (2007–8). In this exploration of communal living, the questions which must drive an appraisal of Eng’s work, which are not formal but discursive, and which set the possibility of exoticisation and exploitation against the power of her works to engender respect, dissolve into a delicate play between the camera and the world it represents. These images propose a world in which a young woman practicing archery takes on the aspect of Diana the Huntress, whilst a couple sit like Adam and Eve in an edenic wilderness, at the edge of which lies a building site. Koch’s camera neither frames the world as it is, nor creates its own reality, but breaks free from this dichotomy into a place which is halfway between document and fantasy.

Una Knox’s film When What Becomes Who (2009) would at first glance seem to bear no relation to the Arcadian fantasy of Koch’s series: it features the conversations of two museum art handlers as they shift vitrines from one floor to another, filmed from a fixed camera in the freight lift they are using. However, it soon becomes clear that this is an orchestrated and highly artificial situation: the technicians are engaged in philosophical debate, and the intervals when they leave the lift to do their work are cut from the film. In fact, this piece shares many of the features of the traditional pastoral: as these handlers lead their flock of containers around, the lift becomes the ‘locus amoenus’ of rest and pleasure, and the labour involved is elided. As William Empson’s study of Some Versions of Pastoral made clear, with its readings of The Beggar’s Opera and Alice in Wonderland, pastoral is more a matter of ‘putting the complex into the simple’ than of dealing with shepherds and cowherds.3 That said, to compare Knox’s film to a pastoral is not to attempt to reduce it to a simple instance of a genre or mode, but rather to articulate some of the pressures that might shape its reading, pushing against her actors’ speeches, whose abstracted and convoluted dialogue strays far from pastoral territory.

A number of works in this show make a virtue of economy, sketching poetic gestures with little effort. Jack Vickridge’s Untitled (Sand on White Slope) (2008) is a small painted piece of corrugated cardboard set at an angle, down which a few grains of sand have been trickled. This minimalist principle can apply across media: Susanne Ludwig’s Feasibility Fantasies (2007–8) features three short video loops, showing a church being transported on a motorised bed, a hot air balloon in the likeness of a church crossing a forest, and an inflatable church being deflated. Meanwhile, Chinmoyi Patel’s sound piece, a simple monologue which mixes childhood memory with fantastic tale-telling, suspends the listener in its unpredictably shifting narrative.

Whilst the preponderance of students from art schools in the capital does raise questions about the London-centric nature of the show – only seven of the exhibitors were trained outside the M25 – this year’s New Contemporaries provides another engaging snapshot of emerging practitioners.

References

1. ‘Selection Video Transcript: May 2009’, in Bloomberg New Contemporaries 2009, ed. Bev Bytheway, Megan Watkins, and Eileen Daly (London: New Contemporaries (1988) Ltd, 2009), no page numbers.

2. Ibid.

3. William Empson, Some Versions of Pastoral (London: Chatto & Windus, 1935), p.23.

-tersea-eng-2008_b.jpg)