Tate Modern, London

23 November 2017 – 2 April 2018

by HATTY NESTOR

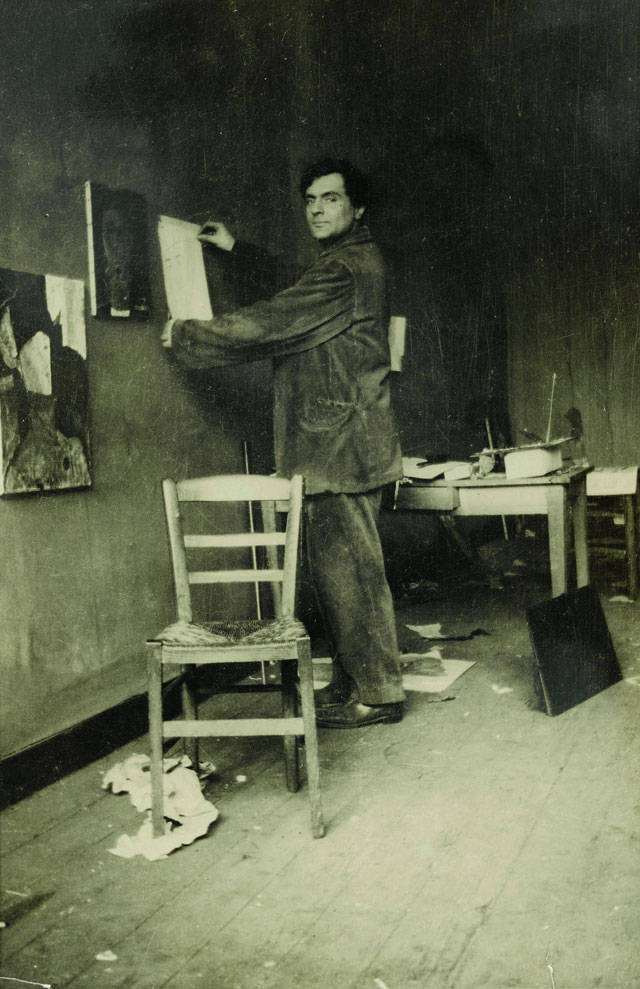

Amedeo Modigliani’s alluring, visceral figures are some of the most celebrated portraits of the 20th century, and this major retrospective at Tate Modern, curated by Nancy Ireson, includes the largest collection of his nude paintings ever shown together in the UK. The exhibition attempts to illustrate the breadth of his practice, with his less famous sculptures and drawings shown alongside the nudes. And, in a first for Tate Modern, it is using virtual reality to enable visitors to imagine themselves in the painter’s final studio at 8 Rue de la Grande-Chaumière in Montparnasse. It seeks to give viewers an intimate window into Modigliani’s environment in early 20th-century Paris.

[image8]

The exhibition is an elegant archive of Modigliani’s short career (he died in 1920 at the age of 35, from tubercular meningitis), displaying 100 works, nearly 40 of which have never been shown before in the UK, and most of which were done during his 14 years in Paris. The breadth of Modigliani’s practice – his eminent portraits, intricate drawings and cubist-inspired sculptures – shown here across 10 rooms, provides not just an aesthetic experience, but a biographical archive of the artist’s life.

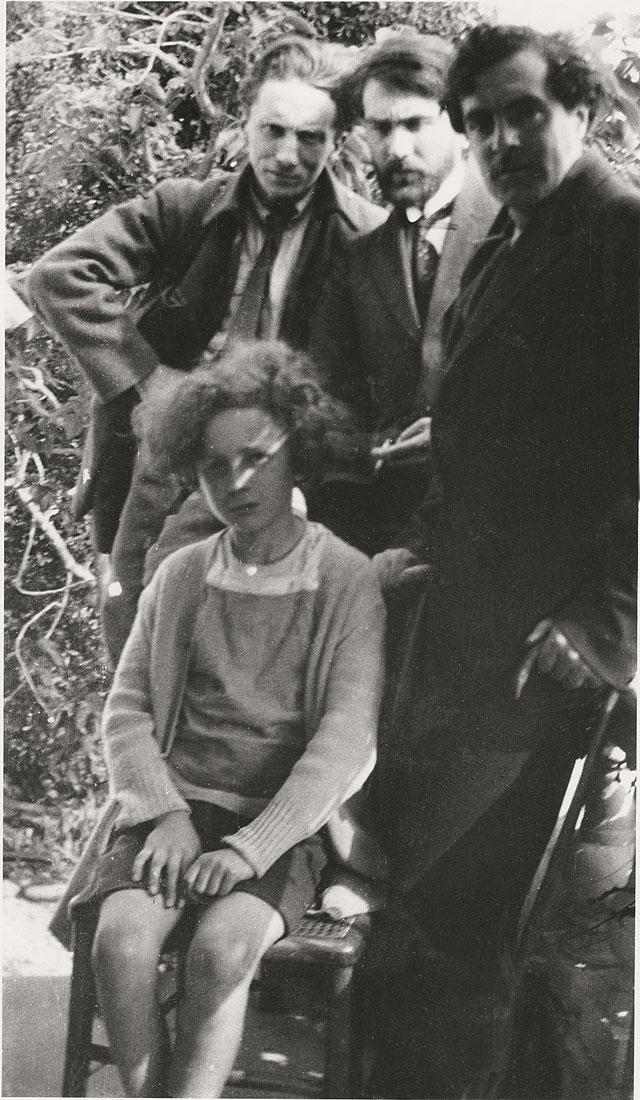

Modigliani was born in Livorno, Italy, in 1884, of Italian Jewish descent. In 1906, he arrived in Paris to pursue his artistic career. It was here that he became acquainted with the avant-garde, living among bohemian writers, poets and artists in the French capital, and becoming renowned as an alcoholic, an opioid user and a womaniser.

[image15]

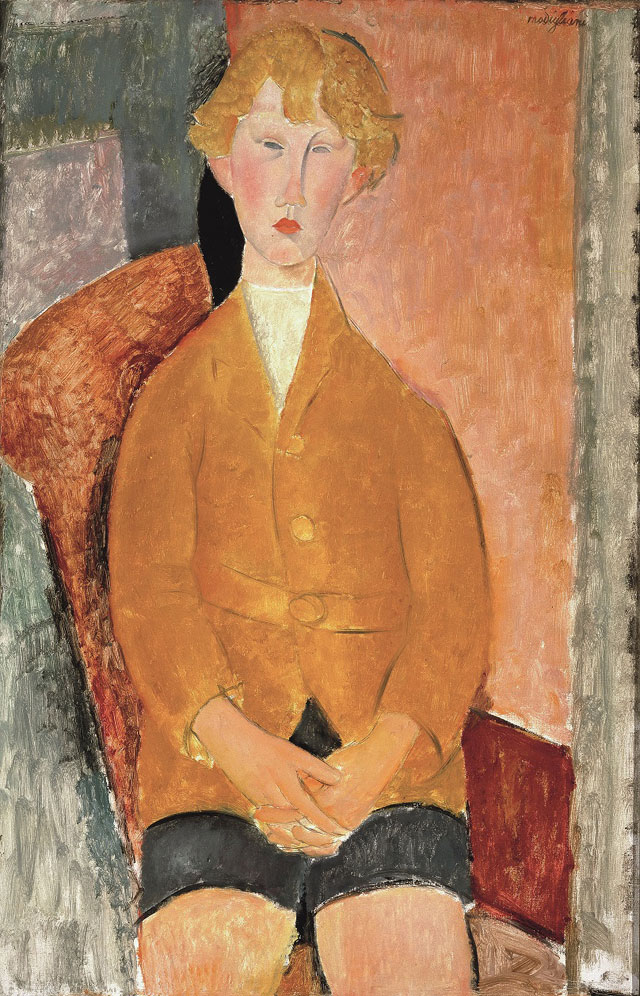

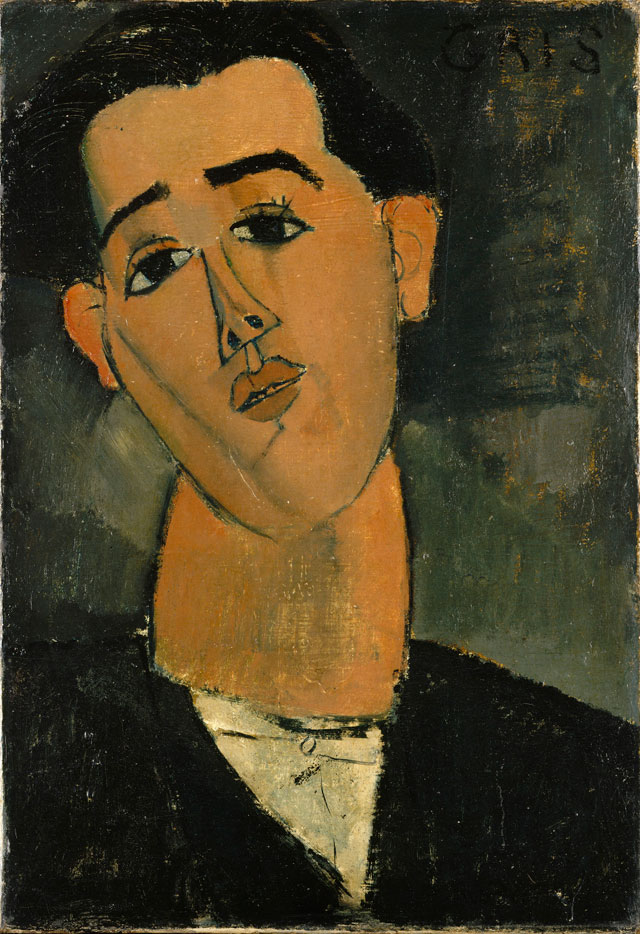

On entering the first gallery, the viewer is confronted with Modigliani’s portrait of Juan Gris (1915) which situates the artists style in a formalist canon, the colours darker than some of his later paintings. A few of the paintings are placed in glass cases, while others are housed in formal wooden frames. The paintings from this earlier period demonstrate Modigliani’s initial experimentation with form and colour – the complexity of his palate – and subtle application of paint. There is, too, Self-Portrait as Pierrot (1915), in which Modigliani is painted as a clown, his expression is desolate, a common characteristic in his portraits. His use of easel, palette and brush is most apparent here, the strokes bold and confident; he appears at ease with a self-depiction.

[image7]

Modigliani’s work is predominantly figurative, his practice characterised by documenting the human body through sculpture and painting. The nudes – for which he is most celebrated – were controversial at the time, often exposing pubic hair, and the subjects’ expressions were calculated and playful. The Tate’s exhibition focuses on the boundaries and intricacies of his life, the work that derived from living among the artistic and intellectual of Paris, and the intimacies of his life, dreams and realities that his work communicates. It is through the faces of those he depicts – often close friends or lovers – that the observer enters into his undeniably brief, but endearing, view of the human form.

[image9]

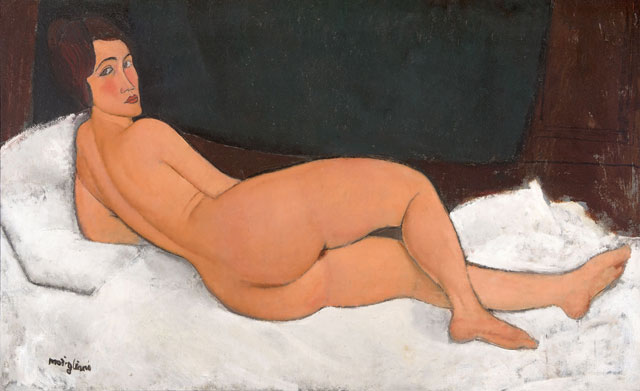

The faces, oval shaped and elongated, are often in almond creams and set against a rich maroon background of bourgeoise rooms, bodies draped across chaises longues.The nude paintings demonstrate how agency is reversed – often the women appear comfortable and relaxed, stark-naked, positioned on their backs or front. The nudes subvert the visual language of the period while, at the same time, resonating in the present as a meditation on the female form as empowering and endearing. This subversion is most apparent in Nude (1917) where the woman, her back to the viewer, peers over her shoulder, her expression calculated and persuasive. The female form here is portrayed as curvaceous and, indeed, desirable.

[image16]

It is conceivable that the mannerisms found in Modigliani’s early-20th-century paintings – the elegant and often wistful figures – still hold great weight a century later. The fifth central room of the exhibition houses 12 of his famous nudes – women who were often sex workers, at times half-dressed, draped across armchairs and sofas. Seated Nude (1917) and Reclining Nude (1919), in particular, demonstrate the figures Modigliani is most famous for – the first voluminous in form and exquisite in expression, the latter relaxed and depicted as landscape, revealing the entirety of the woman’s body. Nevertheless, both seem to suggest a longing, or misplacement of feeling, where the viewer peers into a subtle intimacy of their lives, an inner story created by Modigliani’s hand.

[image17]

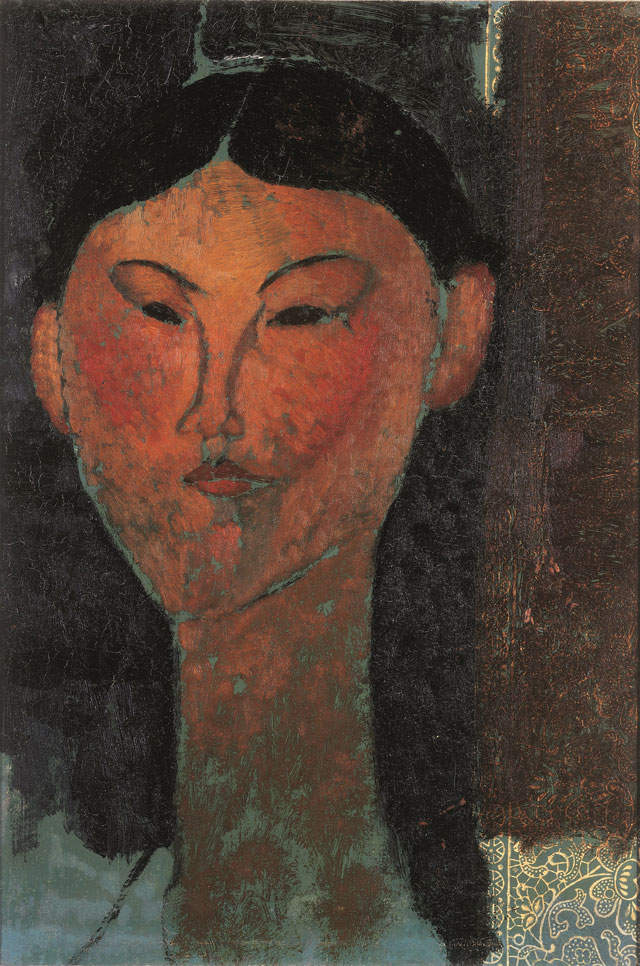

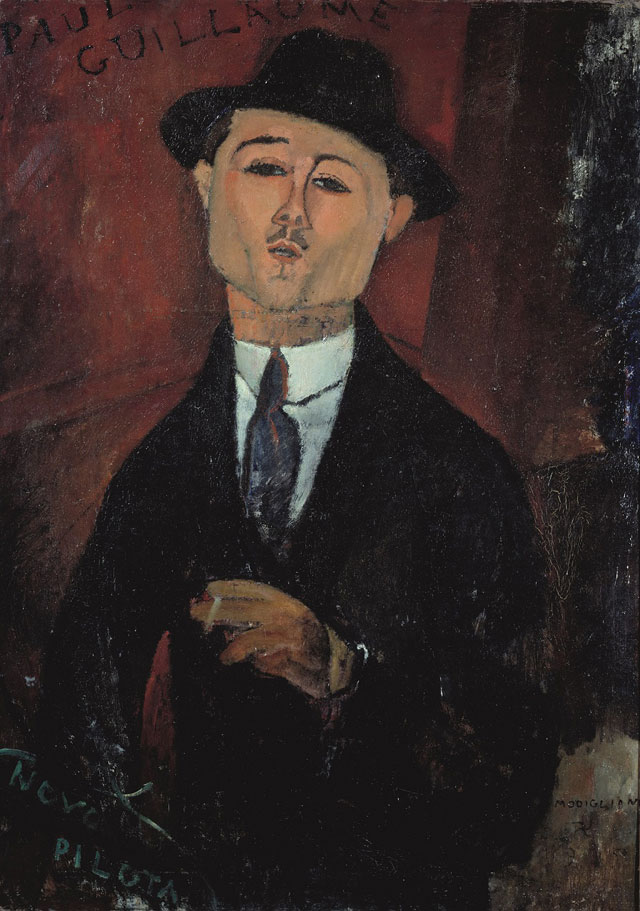

So comprehensive is the exhibition that Modigliani’s less-famous works are also on show. His sculptures Head (1911)and Woman’s Head (With Chignon) (1911-12), in particular, demonstrate the influence African art had on him. Head (1911) is square, less soft than his nudes, with hints of primitivism in its formation. Between 1911 and 1913, while living in the less commercialised areas of Montmartre and Montparnasse, Modigliani became particularly interested in sculpture, influenced by artists including Constantin Brâncuși and Jacob Epstein. This room, which focuses on his sculptures and drawings served to show that the work of artists, even if their medium is narrow, often translates to other forms. This is perhaps surprising in the case of Modigliani, whose figures are his most famous works, and, indeed, his most lucrative. The correlation between his sculptural work and painting is most readily seen in Beatrice Hastings (1915), the woman’s head cubist in form, jagged and square, yet retaining an ephemeral quality and individuality of character.

[image10]

Modigliani left Paris in 1918, residing in the South of France before returning to the city for the last few months of his life. Here, as well as painting local people, the subjects of his work were those close to him, romantically and platonically. And thus, the exhibition concludes on an intimate note. The final room displays the portraits of Modigliani’s lovers, of note Jeanne Hébuterne (1919), who killed herself after Modigliani died. The portrait portrays her unapologetic expression looking somewhat reserved, her face elongated, perhaps haunted by the artist who met her gaze. Their relationship was infamously turbulent and a sense of this is captured in Jeanne’s portrait. A powerful, emotive moment in which to conclude the exhibition, and an affecting reminder of the entanglement of private and public, real and imagined, in Modigliani’s work. The art critic Arthur Pfannstiel, who followed Modigliani’s practice closely, wrote of this blurring of real and imagined in 1929: “The life of Modigliani, wandering artist, so often resembles a legend it is difficult to determine fact from fiction.”

[image14]

I left the exhibition feeling that I had been given a biographical account of Modigliani through his figures and life’s work. It was a life-affirming show that demonstrated the capacity of exhibitions to transcend temporality – giving present space to some of the most fascinating artists of our past. Modigliani’s interior being and character is grafted onto his subjects, a double bind of experience that is still captivating today.

,-1911-12.jpg)