Victoria Miro Venice

20 July – 8 September 2019

by HATTY NESTOR

Milton Avery evokes “complex states of self-consciousness through matt surfaces that yield intense colour saturation”, the art critic Siobhan McDevitt wrote, in a review of the artist’s work in 2002. The American painter (1885-1965) was renowned for depicting his everyday life – family, landscapes and domestic objects – in lucid, pastel and primary tones. Curator Barbara Haskell once said of Avery that it was “as if work itself would provide a deliverance from the terrors of everyday reality”. A sense of intimacy haunts his work. Avery practised among abstract expressionists, yet, unlike his peers Mark Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb, who often concerned themselves with abstract immateriality, Avery undertook a more representational approach to figurative art and the portrait.

This summer, the beautiful Victoria Miro gallery in Venice is exhibiting portraits from 1960-63, the last years of Avery’s career. As the publication accompanying the exhibition notes: “The contours of the faces and bodies reflect each subject’s distilled characteristics while serving to animate the space within the composition.” The collection of portraits shows the rich tapestry of Avery’s lived reality. Venice provides an evocative setting for his portraits – the dream-like quality of its canals and emerald green ethereal waters providing its own nostalgia.

[image2]

Arriving at the exhibition, I was initially struck by Lavender Girl (1963), a portrait of the artist’s daughter, March. The violets, greys and navies are washed out, reminiscent of a fragmented memory. March’s body is slightly disproportionate, her torso, square and angular, dominating the painting. The pastel tones make for a porous, melancholy composition. She rests her feet on a table, behind her a streaked blue background, which one assumes is the sea. This renewed focus on the human subject rather than the landscape was typical of Avery’s work in this period: it often favoured the people closest to him.

Like many artists, Avery’s practice became profitable after his death; while he struggled financially throughout his lifetime, his paintings now sell for between $2m and $4m (£1.6m and £3.3m). During his early years, he lived in Connecticut, working in blue-collar jobs from a young age to support his practice. Perhaps due to these struggles with capital, Avery’s subject matter and visual vocabulary are often concerned with the natural world and humans, devoid of the economic structures he fought against. By the time the portraits exhibited here were created, Avery was living in an apartment in Central Park, New York. Largely confined to the flat because of health issues, he occasionally ventured to Central Park for fresh air.

[image3]

Portraits function as a window on to a person’s characteristics and attributes. They have the capacity to communicate feelings and emotions and offer the opportunity to contemplate the visual fabric of another’s life. A slightly different figurative sentiment – and indeed meditation on portraiture – is found in the self-portrait Milton Avery (1961). A looming, male figure takes centre stage, dressed in pale clothing, with a blackened road creating perspective. He has an uncanny expression – one that does not appear in his other portraits. Here, Avery appears reserved and unsure, tender, recoiling a little. As a viewer, we ask: was this Avery’s own, inner self-perception?

In Two Poets (1963), there is a shift in Avery’s palette. Two figures occupy the painting, placed next to a potted plant and situated in front of a roughly sketched royal blue backdrop. The faces seem submerged, generating a dreamlike feel of the supernatural made accessible. These Peter Doig-esqe colours make for a moody composition, one that allows the viewer to feel the serenity of Avery’s artistic pursuits and reimagine the world in which they inhabit; sublime homages to the everyday.

[image4]

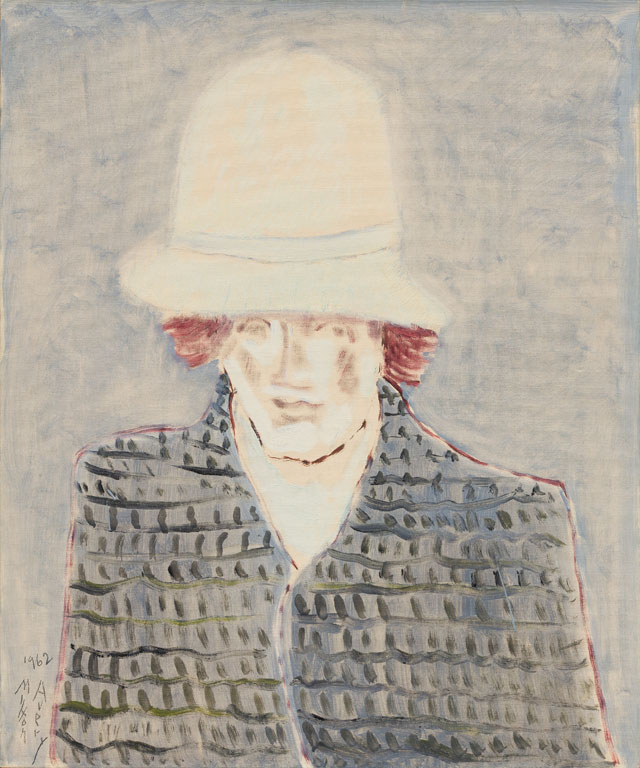

In New Hat (1962), Sally, Avery’s wife, is caught off guard, as she bows her head against a grey background. The attention here, as in many of Avery’s works, is on the characterisation of the subject. The woman appears sombre, her expression hidden by her cautious, non-confrontational stance. The tall cream hat she wears takes up a third of the painting. Sally by the Sea (1962) is another tender depiction of his wife, an affectionate, nostalgic portrait. Wearing a bonnet, a yellow top and a purple skirt, she sits, one leg bent. She seems older and more contained than in some of Avery’s other portraits of her.

[image5]

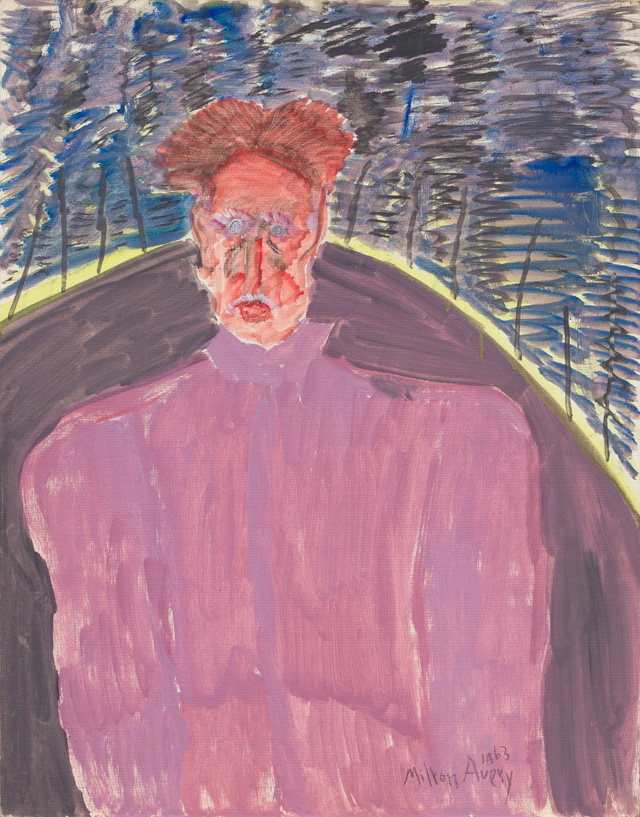

We return to a depiction of Avery’s self in Avery Feeling Wild (1963), where, unlike in the self-portrait, he appears feral and unhinged. His face is red, his expression staring, his shoulders hunched, his hair standing on end. The colours are more aggressive – purples and browns – and Avery appears to be transfixed in a state of rage. The background, comprised of harsh squiggles appears to show abstract trees. Yet there is also a childlike quality in Avery’s rough pencil marks and innocent scenes.

Expressive power emerges from Avery’s lucid abstractions of the human form; he manages to translate the everyday into something other, ungraspable. In Artist Paints Artist (1962), he shows Sally depicting him on canvas, manifesting as a jointly shared portrait. There is an exchange here – not just the painting’s ability to capture a duality and creative partnership, but also in the couple’s desire to archive their relationship through the pictorial. They also appear together in Young Couple (Husband and Wife) 1963. Both Artist Paints Artist and Young Couple feel like an adulation of their relationship; an account of their lives together.

Despite Avery’s financial instabilities, this exhibition is a testament to his unwavering drive to create, document and translate the world in which he lived. Seeing these paintings give the feeling that the viewer is being permitted to peer into a highly personal side of Avery. His work weaves daily occurrences with the individual, personal and private – it is a tapestry that feels pertinent today. Avery demonstrates how a visual framework can retell a story that otherwise might cease to exist; that images can be a carrier of memory, in any temporal moment.