by ANGERIA RIGAMONTI di CUTÒ

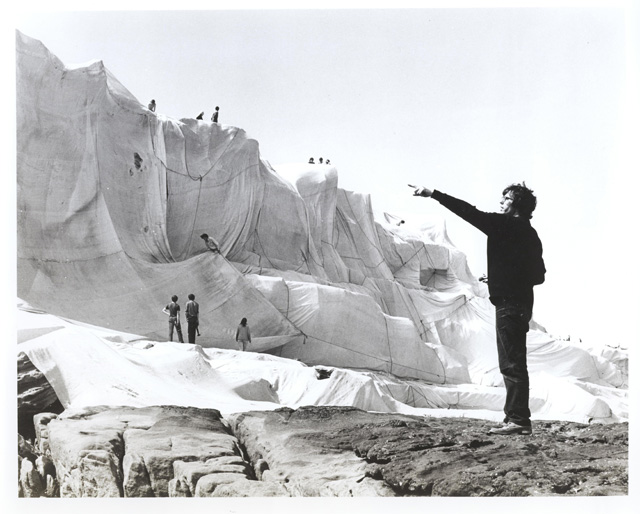

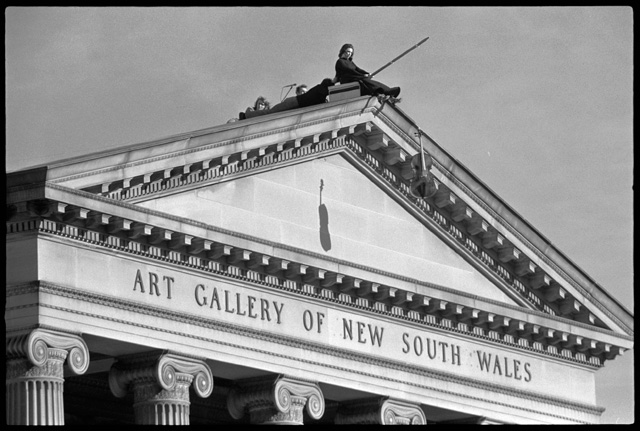

In the winter of 2001, while Michael Landy (b1963) was preparing to methodically obliterate all 7,227 of his earthly chattels in the former C&A building on Oxford Street in London, John Kaldor (b1936) turned up uninvited at 8am, blagging his way into Landy’s radical-industrial destruction fest. Such never-take-no-for-an-answer tenacity is, by all accounts, typical of Kaldor and probably crucial to the realisation of the project that launched his public art enterprise: Christo’s wildly ambitious shrouding of a million square feet of Sydney’s coastline in 1969. A Hungarian émigré, with a day job as a textile industrialist, Kaldor went on to create Kaldor Public Art Projects (KPAP), commissioning 34 artworks by international artists, free to the public, thus promoting Sydney as distinctly progressive at a time when it was seen as anything but. Subsequent projects typify the wantonly expanding field of postmodern art, with contributions ranging from the poignant to the flamboyant, by artists and curators such as Gilbert & George, Harald Szeemann, Nam June Paik, Richard Long, Sol LeWitt, Marina Abramović, Vanessa Beecroft, Jeff Koons and Jonathan Jones.

[image2]

The 2011 project was created by Landy, with whom Kaldor forged a relationship at the time of his impromptu visit to Breakdown. For the 50th anniversary of the KPAP, Kaldor has invited Landy to act as artist-curator, reimagining the 34 works using the archives as his raw material. The call to resurrect lost art is intriguing given Landy’s indelible association with dematerialisation, certainly in the gutsy Breakdown, but also in performative installations such as Scrapheap Services, Art Bin and Closing Down Sale, though there is also a distinct strand of metamorphosis in some works.

Kaldor’s Public Art Projects have also been commemorated cinematically in an immensely watchable documentary, It All Started With a Stale Sandwich, a film that portrays the occasionally comical hostility Christo’s Wrapped Coast provoked, as well as touching more widely on Australia’s complicated and evolving sense of cultural identity.

[image3]

ARC: Given your destructive tendencies, it’s intriguing to imagine you as a curator, a role that still has clinical connotations despite its vamped-up evolution. For this exhibition, you’re completely re-enacting the original works so it’s more as if you’re taking on the role of the artist, or even artists, all 30-odd of them. Were you surprised to be ostensibly cast in the role of curator, and how did you approach the task?

Michael Landy: My relationship with John is very direct and when he asked me to create the exhibition for the 50th anniversary of the Kaldor Public Art Projects – which began when Christo wrapped the coast at Little Bay – I began by looking at his archives because the projects no longer exist. It’s not something I would have expected, but I wouldn’t call myself a curator, I’d call myself Top Dog, that’s what they call me there [a reference to the de facto leaders of the women’s prison in the Australian soap opera Prisoner: Cell Block H].

[image4]

ARC: Apart from your longstanding fascination with Jean Tinguely, your work seems more interested in social systems than in the realm of art. Did it seem quite distant to you to be using art, or at least the archival remnants of art, as your building blocks for this exhibition?

ML: I have no archive myself –

ARC: Famously so.

ML: But it helps that it’s other people’s archives, materials they’ve collected over the years. It’s a release for me. I initially proposed all sorts of ideas but, ultimately, it’s a conversation with John, who instigated the project but also mediated my relationship with the archive.

ARC: The last time you were let loose with other people’s art, in Saints Alive, you performed a process of substantial transformation. You dramatically made the works your own, but in this case are you trying to respect the artists’ visions more than you did then?

ML: I have to, and for me that’s the hardest part. I’m using the archives literally as malleable materials but, of course, I need permission from the artists and you’re a hostage to fortune. We’re trying to protect the artists’ work, but I’m also trying to put on an interesting exhibition and the two things don’t always necessarily work together. But I haven’t really dealt directly with the artists. It’s John who has the relationships with them that he’s built up over the years.

[image5]

ARC: You’ll also be regenerating your own work given that one of the 34 projects was your Acts of Kindness, a project that mapped out the location of acts of compassion between strangers in Sydney. Did you approach your own contribution as you did the others?

ML: Obviously, with my own work I’m at liberty to do what I want and don’t have any constraints. But in each case the main thing was to come up with something physical when an archive has nothing concrete. Also, the projects no longer exist, but they are mapped on to the Australian psyche – Christo’s Wrapped Coast is part of the national curriculum. I even went to Little Bay to see if I could find some remains, but there was nothing, even though it spanned about 1.5 kilometres of shoreline and used about a million square feet of fabric to wrap the coast.

[image13]

ARC: The exhibition also functions as a kind of retrospective of some major streams of postmodern art. Did reimagining your own contribution alongside the other projects make you think about your place within that story? Some of the artists must have been something of a gamble at the time, but many are now a fundamental part of late-20th and early-21st-century art history.

ML: I hadn’t thought about that aspect. I don’t even know how John instigated a lot of the projects. I think that through Christo he met Harald Szeemann [curator of the second Kaldor Project] and Gilbert & George. But what really stands out in the archive is John’s persistence and perseverance, if you also think that, at that time, it took a real mental and physical leap to get artists to go all the way to Australia, so he was really taking a punt.

[image6]

ARC: Presumably for the viewers, too, exposure to those artworks would have been a leap into the unknown?

ML: Yes, obviously that was part of John’s idea, to bring international artists to Australia at a time when he didn’t think the contemporary arts scene was that well-furnished, so that was part of his remit. Not now, but in the late 60s and early 70s there was more of a need for that. John’s also got a Living Archive with local people’s recollections of the projects, like taking bits of material away from the Christo, both physical manifestations of the work and memories.

[image7]

I always bring up Tinguely’s Homage to New York and, for that, I tried to track down as many people as I could who remembered the 1960 performance. At the end, there’s a recording where you can hear people pulling the sculpture, taking bits away with them which he signed. I tried to create a documentary through people’s recollections of this old bit of mangled material. It’s similar to the Kaldor Living Archive in that it’s a trigger reminding people of their first encounter with the work. The Living Archive provides another means of representing 34 projects that aren’t physically present.

ARC: Can you give an idea of the form some of your recreations of the original works have taken for the exhibition? What were the difficulties of translating public and sometimes vast or performed or site-specific works to the constraints of a museum?

ML: I’ve essentially created archive boxes. For some of the performances, I’ve used film, for example for Vanessa Beecroft’s project. For Nam June Paik’s and Charlotte Moorman’s work, it’s more archival – they have the original cello. At the time, they did about 40 performances of the work, so, in that case, the presentation is more documentary, though I’ve tried to get away from that as much as possible. For the Stephen Vitiello sound installation, we’ve got him in a bird box. The birds in Australia are very loud: our birds cheep and chirp; there, they squawk at four in the morning. For the Allora & Calzadilla, I’ve cut holes in the box where you stick your head through – in the original work, the performer played Ode to Joy from within the piano, moving around. For Gilbert & George, I’ve made a musical box that rotates. When they sing Underneath the Arches, they move in a very robotic way, so I’ve made it like a singing musical box where you don’t see them, you just hear them.

[image8]

ARC: The project that most reminded me of some of your work is Santiago Sierra’s portrait of the labour economy with minimum-wage employees holding casket-like structures on their shoulders for the whole day.

ML: For that, we’ve converted our box into a white casket-like container with the project number on it. There are all sorts of pay laws in Australia and they were given the Australian minimum wage – which is apparently quite generous – so it might have been a bit self-defeating for Santiago’s work. I did Scaled Down at Thomas Dane last year, where I compressed a whole body of work under a 50-tonne press, works in the gallery inventory that were unsold, so I thought we could recycle them, re-form them in a different way. I suggested that for John’s archive, squashing the archive into one column.

[image9]

In my own work, I daydream, and ideas just start to pop into my head, but here I couldn’t necessarily execute all my ideas. For instance, I had wanted to look at projects that had failed, and their legacy, because that interests me.

ARC: Which is what you did with Art Bin.

ML: Including ideas I’d had for my contribution to the Kaldor Projects that didn’t happen, like making Sydney Opera House disappear and putting a bend in Australia’s longest straight road. Or, with other artists, not necessarily works that had failed, but proposals they’d sent in that, for whatever reason, hadn’t gone further. I’m interested in all the ideas that no one gets to see because they’re unrealised, so they just end up in sketchbooks. Because people are intrigued about how artworks come about.

[image10]

ARC: Did your view of the artists or the artworks sometimes change as you dug into the archives and reimagined the works? You must have felt more drawn to some than others?

ML: I’m drawn more to the Christo because that’s the beginning of it all and that’s the model that everything else is based on in a sense. It’s funny that the first project is the most well-known, for all sorts of reasons. It entered the national psyche, through tabloid newspapers – Australians love to poke fun at things. I wanted to call the show Mate, What’s This Shit? because a guy on a skateboard came up to John when he was looking at 21 Beach Cells by Gregor Schneider and said: “Mate, what’s this shit?”

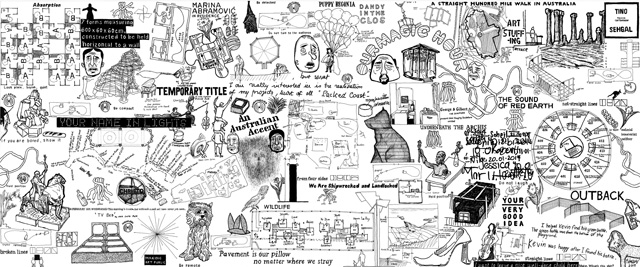

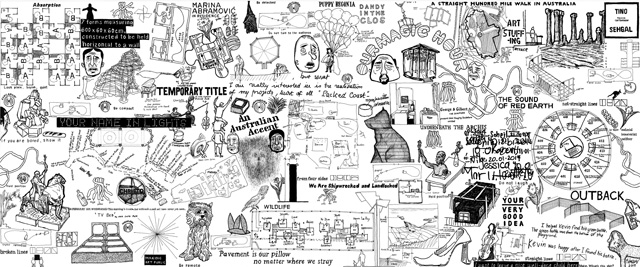

ARC: Though you have given that title to the vast illustration you’ve created for the exhibition.

ML: I was determined to use it somewhere.

[image12]

ARC: The illustration reminds me of the amazing drawings you made for Scrapheap Services, with their densely packed, cartoon-like detail that’s still very legible. Did you deliberately make it look like a recognisably Michael Landy drawing?

ML: For Scrapheap Services, it was of a diary of a production of an artwork made over a number of years. The drawing for John was along similar lines and because I don’t make the kind of drawings I made for Scrapheap Services and Michael Landy At Home any more, it was interesting to go backwards. I’ve also used details of this illustration for a floor path we’re making so people can choose to follow one particular project – it doesn’t go in chronological order.

ARC: You notoriously blitzed your own archive in Breakdown. Here, you’ve used the archives to re-form the artists’ works for the exhibition. Did this make you rethink the destruction of your archive? You’ve often said you never regretted Breakdown, but has your relationship to it ever shifted with the passing of time?

ML: No, I’m still solidly behind the idea that if I can destroy my archive, I can destroy anything. I ended up in debt.

ARC: Being pragmatic, you could argue that it was a good investment.

ML: Yes, but that’s not why I did it. What really interested me was people witnessing it, seeing the thoughts and feelings that people brought to it. All artists dream about people talking about their work, responding to it and remembering it. No one wants to make art that people forget.

It’s the same with John’s projects: the Christo is now part of the Australian psyche and even part of the landscape. The Richard Long work as well, when he walked 100 miles over eight days and made a line of red stones. I always like the idea of going back to a Richard Long and kicking it over years later. You only ever see the photographs of Long’s work, but you never see how it deteriorates and becomes part of the landscape.

• Half a Century in the Public Eye: A collaboration between Kaldor Public Art Projects and the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia, runs from 6 September 2019 until 16 February 2020.