Centre Pompidou, Paris. 11 September 2002-6 January 2003.

Tate Modern, London. 13 February-5 May 2003.

MoMA QNS, New York. 26 June-29 September 2003.

The Great War played a significant part in prompting Beckmann's fascination with disaster. He served as a hospital orderly on the Belgian front. Peter Selz described Beckmann's experiences in Flanders as looking 'horror in the face every day'. He drew what he saw but was badly affected and was discharged from the army suffering emotional exhaustion. On leave in Brussels in 1915, Beckmann was able to visit the museum there to see the work of Bruegel, Roger van der Weyden, Cranach and unknown German primitive painters. Beckmann identified with the work of Grünewald (the Isenheim Altarpiece) and developed a great passion for late medieval art which is evident in paintings such as 'Carnival' (1920), acquired by the Tate in 1981. The theatricality, the world view implied in medieval painting informs Beckmann's subjective symbolism.

[image3]

'Max Beckmann' at Tate Modern is the first major exhibition of this artist in this country in over 40 years. Waldemar Januszczak believes that the exhibition, 'makes clear that the received wisdom about Mad Max is essentially inaccurate', that Beckmann's rage was very much his own. The exhibition brings together approximately 75 paintings, several sculptures and a number of significant prints and drawings. The show examines three pivotal periods in Beckmann's career: 1918-23, 1927-32, and the late 1930s to 1940s. Following the successful collaboration for 'Matisse Picasso', Tate Modern has organised the Beckmann show in association with Centre Pompidou, Paris and the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Beckmann lived in Paris and New York and visited London. A major catalogue is published to accompany the show.

As a young artist, and before his experience of war. Beckmann aspired to becoming a history painter. His ambitious 1912 painting of 'The Sinking of the Titanic' is also the largest in the show – a vast 8' x 10'. It was inspired undoubtedly by Géricault's famous 'Raft of the Medusa', a painting central in importance to the current exhibition at Tate Britain 'Constable to Delacroix', devoted to the British influence on French Romanticism. The original was not fit to travel, so Tate Britain have used a 19th century copy, cleverly lit. However, even this copy has more power, however than Beckmann's Titanic painting in which his figures scream but fail to convey the power and integrity of Géricault's great and influential work. Beckmann's work is comparatively hollow and insubstantial.

Following Beckmann's war experience he painted 'The Night' (1918-19). It is an early example of Beckmann's grotesque and appalling visionary paintings. The scene takes place in a cramped room in a modern city, even though (in his own words) he was attempting to produce a large modern history painting with a whiff of evil about it. The wretched figures include a crucifixion with two martyrs, a man hung by his neck while a man with a bandaged head, wearing waistcoat and tie and smoking a pipe, twists his arm. Two women are included in the scene: one in red stockings is bound to a post; the second is held upside down by a man whose hat resembles the type worn by Lenin. Phallic suggestions, an uncertain air of suffering and possible perverse pleasure co-exist. This is a scene of urban hell, an unfathomable and vile scene.

Beckmann's reference to the night as the title of the painting suggests an interest in the imagery of dreams that interested the Surrealists. Yet Beckmann's unconscious has practically nothing to do with his Surrealist contemporaries. For Max Ernst the night was another world where mystery abounded and insight was attainable; for Beckmann, the night was an excuse for arbitrary madness.

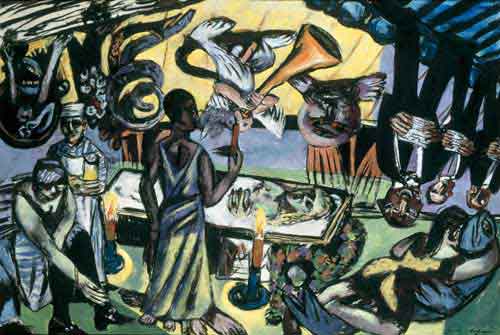

Soon after 'The Night', Beckmann painted 'Carnival' (1920). The masks and costumes used were based on those worn during the carnival scenes in Catholic countries between mid-January and Lent. They are employed by Beckmann to symbolise vanity, futility and the transience of life, to emphasise human mortality and one's ultimate destiny. The use of bright colours, the zig-zag lines across the canvas that are in contrast to the rigid stance of the figures and the cramped picture space, create unease and stress, pictorially. His work contains echoes of Modernism - Cubism and Surrealism, in particular - yet a psychological tension that refers to man's relationship to society in post-war Europe. For Beckmann, war emphasised the individual's spiritual isolation. In his Artistic Confession (1918), he wrote:

…the deeper and more fiercely my despair about existence burns within me, the more determined I become, with lips tightly sealed, to capture the disgusting, throbbing monster of vitality, and to capture it, suppress it, even throttle it in crystal-clear, incisive lines and surfaces.1

In his 1938 lecture 'On my painting', Beckmann stated:

My dream is the imagination of space - to change the optical impression of the world of objects by a transcendental arithmetic progression of the inner being.. …For the Ego is the great veiled mystery of the world…I believe in it and in its eternal, immutable form. Its path is, in some strange way, our path. And for this reason I am immersed in the phenomenon of the Individual, and I try in every way to explain and represent it. What are you? Who am I? Those are the questions that constantly persecute and torment…2

As many as five hundred works by Beckmann were confiscated by the Nazis because they were considered to exhibit all that was depraved, diseased and worthless in modern art. After hearing Hitler's speech on the radio (1937) in which he denounced modern art and referred to the 'gruesome malfunctioning of the eyes' of the artists, Beckmann left Germany the following day for Amsterdam and never returned. 'The Night' is perhaps a prophetic image of Hitler's Germany, a society that, in Beckmann's view, allowed itself to be tortured from within.

Beckmann's highly personal vision drew on his engagement with Modernism, Abstraction and a profound personal crisis provoked by Nazism and his subsequent exile from Germany. Although he has been historically affiliated with Expressionism and Neue Sachlichkeit, Beckmann's art was primarily the product of his personal response to the spirit of his age. The rise of Nazism and the shock of exile left a profound effect on Beckmann. He came to believe that his moral purpose was to depict the horror of contemporary life. In 1937 he left Germany for Amsterdam where he lived in exile for a decade. He spent his last few years in America, in New York.

On Boxing Day 1950, Beckmann put the final brushstrokes on 'The Argonauts'. It was a less disturbing painting than 'The Night' and, indeed, most paintings in his impressive oeuvre. The following day he left his studio in Manhattan to walk across Central Park to the Metropolitan Museum where his 'Self-Portrait in Blue Jacket' had just been hung. On the way he collapsed and died of a heart attack, aged just 66. The present Tate Modern exhibition is the first showing of 'The Argonauts' in Britain, described by curator Rainbird as, 'an incredible last blast from the orchestra'.3

This is an overwhelmingly disturbing exhibition by one of the 20th century's most vehement artists, and particularly poignant in the present political climate.

1. Max Beckmann, 'Artistic Confession', quoted by Sarah O'Brien Twohig, Beckmann Carnival', Tate Gallery Publications, London, 1984.

2. Max Beckmann, Foreword by Mayen Beckmann, Afterword by Sean Rainbird, Tate Publishing, London, 2003, 16-18.

3. See Max Beckmann, edited by Sean Rainbird, Tate Publishing, London, 2003.