The Met Breuer, New York City

15 March – 18 June 2017

by JILL SPALDING

Who would have thought that, defying the theatrics currently spotlighting young American artists at the Whitney Biennial, the show of the season would be a quietly radiant assessment in its former space of the work of a much older one. But here’s the thing about Hartley, the bonfire painter who burned so bright from the start of the 20th century until reduced to a flicker by the padding of time and a woodpile of new masters; hugely influential to this day, his is a gigantic talent that has been hiding in plain sight.

Having found early success for one vernacular that overshadowed another, his work has remained completely familiar and largely unknown. Think German officers and you say “Marsden Hartley”; reference the craggy Maine landscape and you call up Rockwell Kent, Frederic Church, John Marin, George Bellows and Winslow Homer. This urgent semi-retrospective at the Met Breuer rights the apple cart – or should I say lobster pot, for one of the standout portraits in a show full of them is of a lobster as ruddy and boisterous as the Laughing Cavalier by Frans Hals.

The timing of this rousing exhibition is exquisite. Spitting in the eye of a controversy over the abrupt dismissal of the Metropolitan Museum’s director, Thomas Campbell, for (among other concerns) embarking on a new wing the budget couldn’t deliver, it confirms the takeover of the Breuer building as a coup. Providing a formal space that, in effect, constitutes a new wing, this noble annex can no longer be viewed as a luxury, but must be held on to at all costs for the majesty it accords work such as this that needs an altar to shine.

A curatorial triumph for how convincingly Hartley’s meditations on Maine present as defining his modernist vision, the show serves as successfully to broaden our understanding of modernism. These burning canvases are not a style, they are a passion – inflaming landscapes so dour to the unseeing eye that only obsession born of innate kinship and a sure brush could ennoble them.

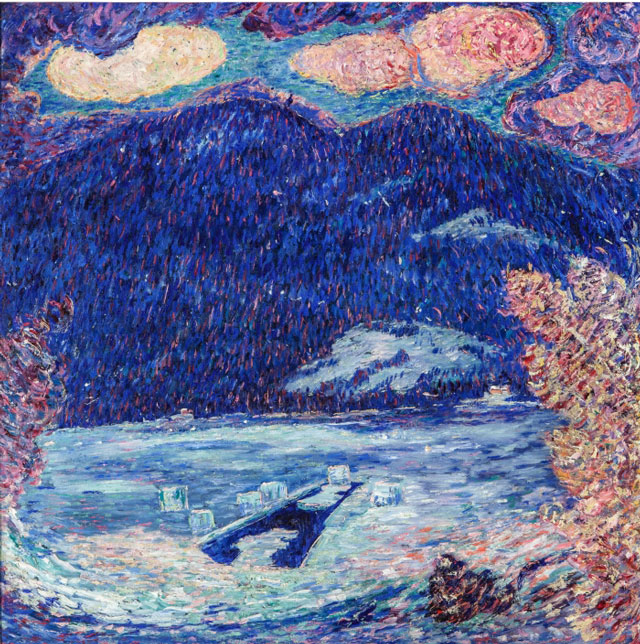

Trace the emotion that animates the logs, steeples and shorelines to a lonely New England childhood, born of the loss at the age of eight of a mother he loved and, too few years later, of a stepmother we know must have mattered since he took her surname, Marsden, for his first. Track the accomplished technique to stints in New York, where the country boy was swept into the touted circle of the gallerist-photographer Alfred Stieglitz; over to Paris, which introduced the maturing disciple to pointillism, collage, cubism and the heady company of Picasso and Gertrude Stein (who bought four of his paintings); and on to the radical detour of heyday Berlin, where immersion in the Blaue Reiter movement and a love affair with a German officer might have rooted Hartley in European modernism had circumstance and a still-latent nostalgia not taken him home. Between visits to Maine, he showed in New York, with enough of a following to have settled him there but for a restless search for new experience that took him to New Mexico, Nova Scotia, Cape Ann and Bermuda.

As it happened, though, it was pique that galvanised Hartley’s marking return to Maine. Yes, he was working and showing, but to dwindling attention. The aesthetic had moved on, drawing on the Arts and Crafts movement and a native awakening to cultural naturalism that were being lucratively marketed as American regionalism. The West had discovered its wilderness (Albert Bierstadt), and the Midwest its heartland (Thomas Hart Benton). Most galling to Hartley, a developing interest in the craggy northeast was taking rival artists to Maine – an affront that could be righted only by claiming the state as his own. The challenge proved salutary. If Hartley moved back to Lewiston to guard his left flank, the memories of his youth unleashed a whole army: branding himself “the painter from Maine” galvanised an outpouring of work that must be seen here to be believed.

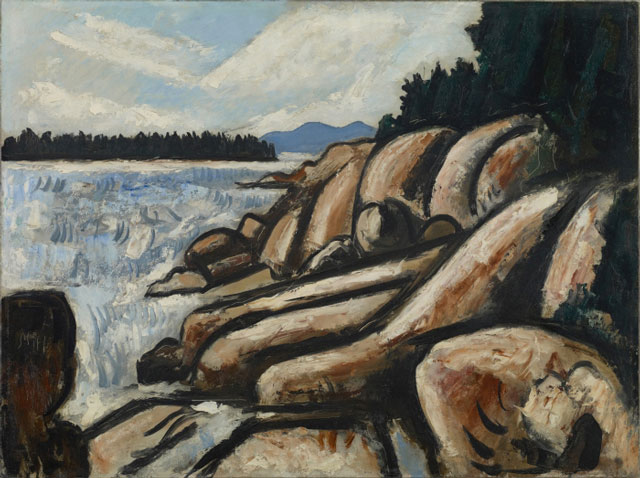

Begin on the fourth floor with a place-setting film of pastel waves lapping at an indeterminate shoreline. It’s a brilliant introduction, but their pale languor is deceptive. Even Hartley’s early mountainscapes, built to ferocity with drenched colour and thick stippling, are the stuff of high drama. Distortion, at once suggestive and searing, of sites seen on postcards – a church, a lighthouse, a landing – renders even the everyday talismanic. White water breaks against black rock with the force of a gale directed by Poseidon; a logjam piles up metaphors of stubbed-out cigarettes and spent cannon; a gap in a lineup of fishermen tells of hardscrabble lives lost to punishing seas. This is not plein-air painting, but rather the distillation of accumulated memories mediated by concentrated acts of looking and the lessons in form, line and tonality learned abroad.

Signature Hartley are his negotiations between the core elements linking earth, ocean and sky. Clouds pooled like ponds, and waves foamed like clouds, call attention to a mastery of techniques loosely borrowed, adjacent works tell us, from Japanese masters of wood-blocking, and reworked through the broken monochromes picked up from Picasso and the drenched colours of German expressionism into a poetic idiom that gives the flat plane the illusion of depth. It helps to know, too, that Hartley was, in his lifetime, an acclaimed writer of verse.

Laid out chronologically, the show builds up an inner rhythm from multiple renderings of the same view, which reveal, thanks to generous loans, Hartley’s inclination to flesh out the subjects that engaged him in a series. There are more takes on a mountain range morphing through various seasons than Monet gave to his haystacks; there is more attention to logs than thoughts of fallen wood could sustain. Hartley’s repetitions are indulged here because they illuminate his process, one of digging down to a primary image and building it up differently with every tool in his playbook. Equally instructive is the curatorial inspiration to pair works selected from the museum’s collection by four of the artists (Katsushika Hokusai, Utagawa Hiroshige, Albert Pinkham Ryder and Paul Cézanne) who changed his direction. It says much about how fully Hartley made their methods his own that the earlier work seems, rather, to borrow from his; Cézanne’s rendering of Mont Sainte-Victoire may have moved the needle, but Mount Katahdin looms larger: only Winslow Homer’s crashing surf, shown alongside in the Met’s great Northeaster, holds its own.

Even the smaller works, included principally, you might think, to charm and delight, serve the larger proposal of an eye directed to every possibility: Hartley’s 1917 oil-on-glass still-life, for example, derived from the lapsed technique of glass paintings finished with tinsel, presents appropriation as one of his exploratory tools.

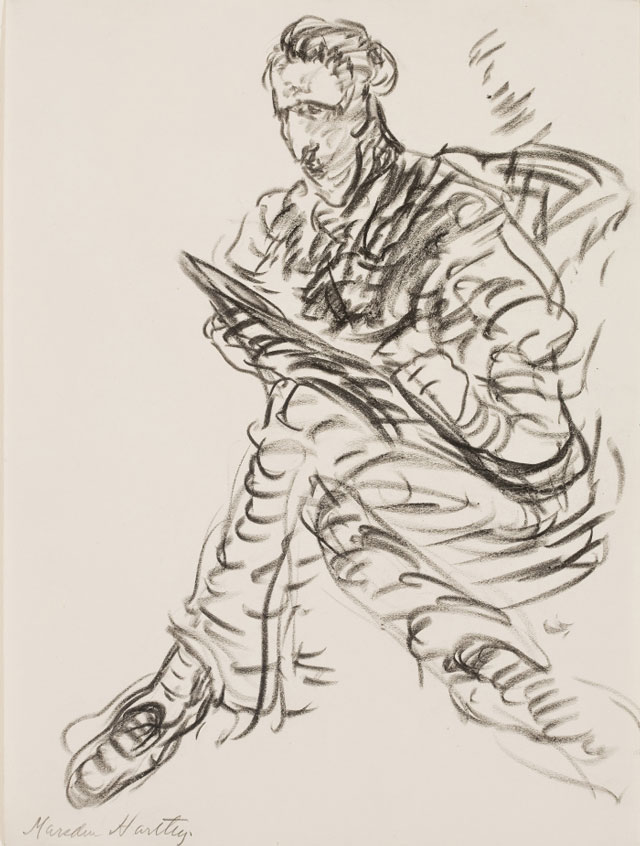

You might not expect drawings to rival here but their inclusion proves indispensable. How else to understand the latent energy that rescues the musclemen from kitsch and roils the large oil paintings with a life beyond image? Given the range of movement that Hartley extracted with short flicks of the pen, it is surprising that Van Gogh is not mentioned as an influence.

The oil paintings, nonetheless, command every gallery. Most compelling are the reversals of nature rendered with visual metaphors that verge on Shakespearian; dead trees shed writhing limbs; mountains rise up from their shadows; a waterfall plummets through a rocky embrace; waves foam into mighty erections.

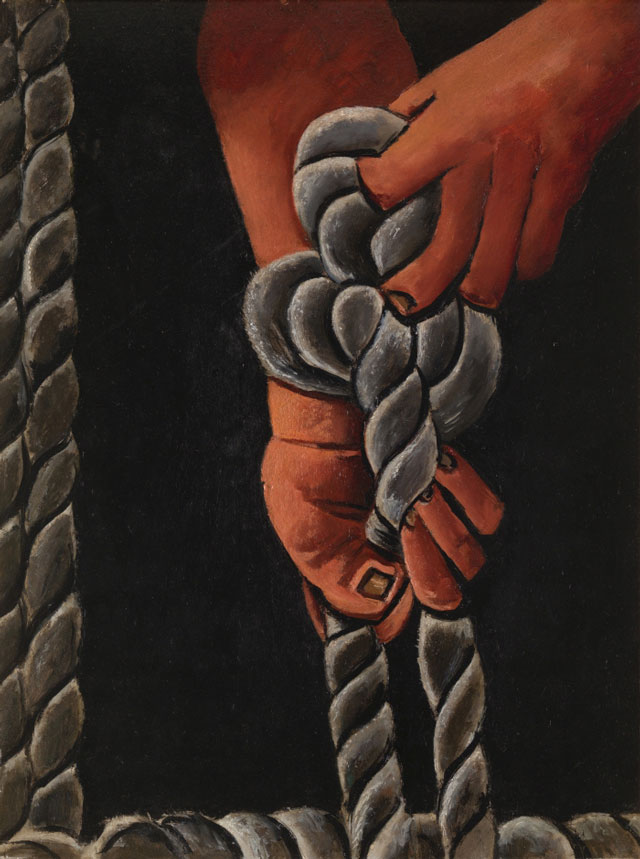

The charge of coded homoeroticism, supported by Hartley’s private correspondence, is borne out by both the early and later work on view here. Three drawings of woodcutters from 1908 link a study involving a lighthouse and an implausibly round rock to an abstracted study of rhythmed movement. Hands tighten on a rope as on a clenched throat. Riffing on America’s superhero fixation, Hartley’s steamy portraits of beach boys bared to the jockstrap blazon proclivities once cloaked with military insignia.

That they are given their due but no more speaks to this show’s penultimate contribution. As with the drawings and photographs depicting the features of this lanky New Englander, they tell only part of the story, freeing the exhibition in its entirety to act as autobiography. The artist’s truest self-portrait, it’s been said, is the lone tree in the foreground of his last homage to Mount Katahdin.

Don’t forget, on your way out, to pick up a roadmap to the actual places Hartley painted. You will want to hold on to the memories, for you will leave buoyed, both for the joy of new acquaintance with an old master and the comfort of knowing that alongside the unseasoned, aggressively collected, new art, the work of an American modernist looms fresh as spring.

.jpg)