Tate Modern, London

5 February – 10 May 2015

by EMILY SPICER

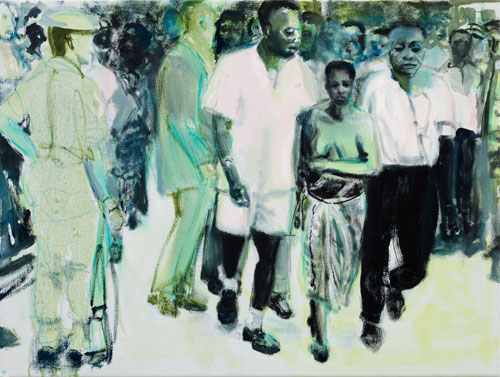

Marlene Dumas’s paintings are born from the most pressing issues of the human condition. Politics, race, cruelty, religion, sex and death; all are explored in paint that seeps and runs across the cockled paper and giant canvases of her life’s work. Her art is provocative, but not shocking for the sake of shocking. Indeed, rather than feeling repelled, you may well find yourself drawn closer to the blue and black eyes of a terrorist or the pink gaze of a stripper looking back at you while bending over to reveal all. Colour is part of the grammar of meaning, and Dumas exploits this tool with the subtlety of a true master. What significance is there in black, or white? What is the colour of lust, or murder, birth or war? Dumas has the answers.

Like so many other painters working in the past 50 years, Dumas (b1953) gets her source material from the endless torrent of media images. Through her eyes, humanity’s problems and preoccupations are rendered in paint, but altered to become something new, imbued with a fresh, if equally troubling, life. “There is the image you start with and the image you end up with, and they are not the same,” she explains in one of many thoughtful quotes pasted on to the gallery wall. “I wanted to give more attention to what the painting does to the image, not only to what the image does to the painting.” Dumas is talking about the transformation that occurs when the photographic image is reproduced as a painting. Paint adds truth, while also taking it away. A painting, in short, is a different animal.

Although Dumas mines sources available via the media, her work is deeply personal as well as broadly relevant. Through her painting, she explores her own feelings, be they about sex, relationships, race or the loss of her mother. But no matter the theme, almost everything about Dumas’s world is unsettling. In her hands, even newborn babies are imbued with a threatening air, and the children on her canvases take on a wild, supernatural quality. Dumas even painted her daughter, Helena, with undeniable layers of conflict and complexity.

Helena looms over the gallery space, a toddler standing two metres tall with narrow, black eyes staring out from an oddly shaped, pale pink face. Her hands, too, are troubling; the left is covered in blood-red paint, while her stomach is a deathly pale blue. Any background that existed in the original photograph has been replaced with a flat, white layer of paint, and her feet are left unfinished, as if she were a fleshy apparition. She is a bemusing paradox, at once an innocent, while also threatening and unfazed; she is a manifestation of what Dumas calls the “cruelty and magic of innocence”. This is The Painter, new and eternal, naive and seeing, the author of her own meaning. But Helena grows up, and, like Eve expelled from the Garden of Eden, becomes ashamed of her body and unsure of her role. Positioned opposite her younger self, the teenage Helena, rendered in a sickly, bile yellow, clutches a towel to herself, no longer meeting our gaze. Her confidence has gone, along with her raw, unfettered directness, leaving an awkward, unassured adolescent.

Room 13 sees one wall dedicated to the delicately painted likenesses of Great Men. This collection of watercolours was Dumas’s contribution to Manifesta 10, an exhibition held in St Petersburg last year in protest at the Russian government’s laws forbidding the “promotion” of homosexuality. Each beautiful portrait depicts a notable gay man from the 19th or 20th centuries, accompanied by a short biography written in pencil. Alan Turing, Oscar Wilde and David Hockney are among the carefully painted likenesses. No distorted features here, for resemblances are important, and these black and white faces are so tenderly rendered, one cannot help but be moved. No matter the theme, Dumas speaks volumes with the lightest touch.

This exhibition is named after one painting in particular, a small dark canvas entitled The Image as Burden, which depicts two figures of indeterminate sex. Convention, however, leads us to believe that the grey, supporting figure is a man, and the pale, robed person in his arms, a woman. In fact, the source for this painting is the 1936 film Camille, starring Robert Taylor and Greta Garbo. The man who carries the unconscious woman is naked. This, the title suggests, is the artist, while the dead weight in his arms is the image. The burdened artist carries the heavy responsibility of his creation, which is vulnerable to interpretation and speculation. Alternatively, perhaps, the “she” is already dead, murdered by neurotic, postmodern analyses. Perhaps, though, this is a comment on the creative process. Any work in progress, be it a film, essay or musical score, can be burdensome, as it will almost always plague its creator with doubt and uncertainty until, and sometimes after, its completion. This painting, like so many of Dumas’s works, is personal and complex.

Throughout this captivating exhibition Dumas shepherds her images, perhaps in recognition of art’s fragile nature; her voice is plastered across the walls, her presence inescapable. Not that her paintings are in danger of crumbling under a scrutinising gaze – in fact, quite the opposite is true. In the accompanying catalogue, however, Dumas’s voice is mixed with that of countless writers and critics who have commented on her work throughout her career. She states that the views of these authors may not correspond with her own, yet they are included and, by that very act, acknowledged as valid. “I am concerned,” she says, “that the image I have constructed of myself will be taken as the only one, because maybe I have got it all wrong.”