by TOM HASTINGS

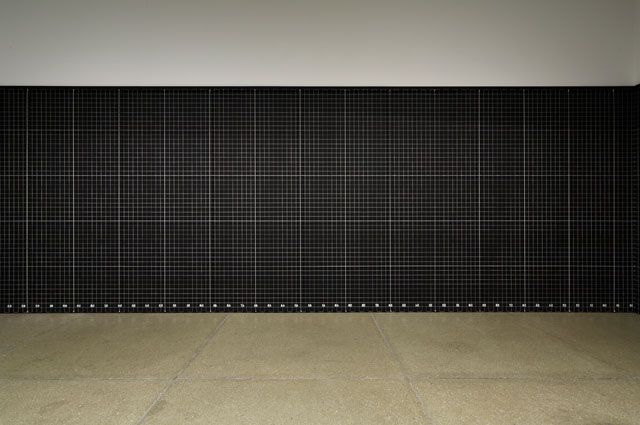

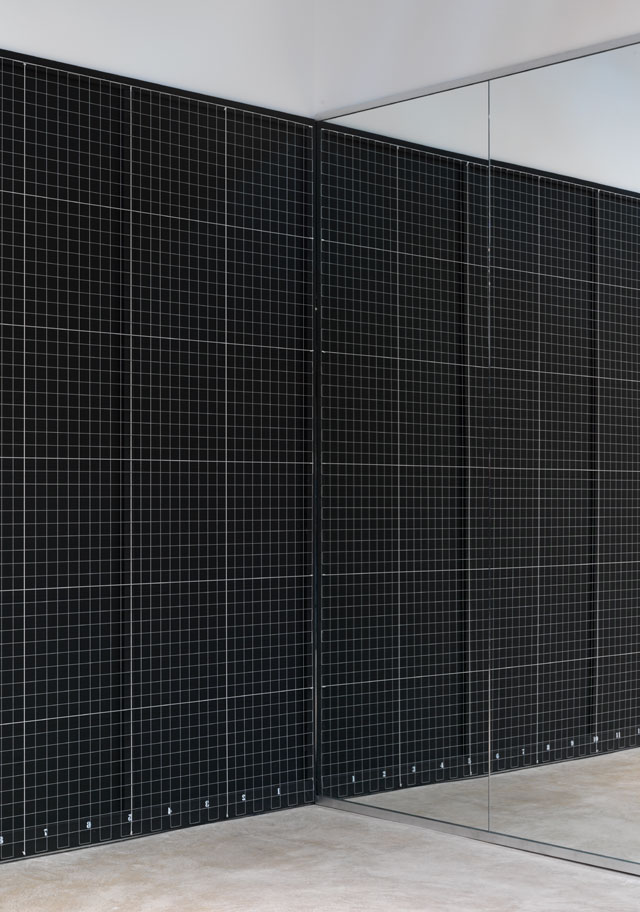

I arrive at the Jerwood Gallery in Hastings to meet Mark Wallinger (b1959, Essex) ahead of the opening of his show. Katie Lineker, the gallery’s marketing and communications officer, leads me through to one of two exhibition rooms, where I find Wallinger conversing with the Jerwood team. Hemmed in on three sides by a floor to ceiling, white on black grid, the felt presence of Eadweard Muybridge, for whose photographed locomotion studies the grid served as a backdrop, is ambiguous. As I wait to speak to Wallinger, Lineker tells me that the three mile-length of white kite string that forms regular interstices across the grid has been painstakingly installed over the black-painted wall using laser placement. Indeed, the installation team seem to have done a good job: the result is pristinely reflected in a “mirrored world” – as Wallinger later refers to it – that covers the room’s fourth wall in place of the imagined photographer. A few unassuming gallery-goers, who have perhaps ambled in to the exhibition or been directed here, begin to walk around the space as the press photographer carries on with his work. Reflected by the mirror, their reassuring presence injects some real intrigue into the show’s title, The Human Figure in Space.

[image3]

Wallinger and I begin our conversation in two different locations before settling down in the upstairs cafe, a spot of relative calm. A row of windows frames a wet summer’s day, and over the masts of Hastings’ beached fishing fleet, the sea morphs into an indistinct grey sky. Over tea and coffee, we discuss the legacy of Muybridge and his significance for Wallinger’s practice. The enigmatic grid, which Wallinger first replicated in 2007, for a show at the Donald Young Gallery in Chicago, was reformatted in 2011 for Undance, a collaboration between him, choreographer Wayne McGregor and composer Mark-Anthony Turnage. As the other works in the show – including Birdman (2018), made especially for it – enter the conversation, a series of interlocking concerns around spectatorship come into focus.

[image12]

Tom Hastings: What is your relation to Hastings and to the Jerwood Gallery, and how did the show come about?

Mark Wallinger: I’ve known Liz [Elizabeth Gilmore, director at Jerwood] for the past few years and we’ve talked about doing something together for a while. I suppose the gallery itself was part of the inspiration, both the architecture and its situation here. I have childhood memories of Hastings. My earliest seaside memories are of the Sussex coast. My mother’s best friend moved down to the south coast at the end of the war, so we spent weeks of the holiday at Bognor Regis. The coast is a very particular situation – there’s quite a primary experience of space, especially for a child. That excitement, that anticipation, and that moment when you kind of know the sea is going to be beyond the next horizon on the way here.

TH: And the hills jutting up behind …

MW: Yes, Hastings has that funicular lift.

TH: The Human Figure in Space reprises the grid used by the British photographer Eadweard Muybridge as the backdrop to his locomotion studies. Of course, he represents a significant resource for many artists: From Sol LeWitt, who developed his method of seriality after a former tenant left a book of Muybridge’s photographs in his apartment, to Yvonne Rainer and others from the Judson Dance Theater’s development of task movement, and more recently, in 2016, Bruce Nauman’s Contrapposto Studies, I through VII, also a revisiting of an earlier work, presents a study of walking positions on video. What initially led you to Muybridge and why has his grid sustained your curiosity?

MW: There are certain artworks that reach through the past to grab you, artworks that contain something that seems completely modern in a way that’s almost anomalous. It’s not just the grid, it’s also the fact that it’s a white on black grid. I suppose you can see it as a paradigm of a different way of seeing. With this show, I’ve taken the Human Figure in Motion, which is Muybridge’s magnum opus book, and exchanged motion for space – in other words, removed the photographic element. I wanted people to inhabit that space, and to vivify what that thing would have been at the time. I’m interested in capturing that aspect of seriality.

[image4]

Perceptually and historically, we’ve gone from the icon to one-point perspective. The grid, in turn, represents society’s shift to modernity, it conjures up Cartesian coordinates and graphs; everything from physics to economics utilises it. From being in the space of the grid just now, the people in it seem very precise and perfectly judged in their movements. I had hoped that would occur. It’s an orientation that provides a modern sense of oneself that would have been different from an earlier stage in history. For instance, you can align perspective with the Reformation: religious painting permitted a personal experience with the deity that was completed by your perception. With The Human Figure in Space, I am interested in actualising that relationship for people. By playing with the fourth wall, if you like – the mirrored space allows for a further self-consciousness – you’re encouraged to become a representation.

TH: I like this idea of exchanging motion for space as that which is caught by the grid. And, in fact, when you’re in the empty gallery room, it could be anywhere, but as soon as the locals from Hastings walked in, it really brought it to life in a particular way. You had the press and photographers there, of course, but then noticeably you had everyday life.

MW: That really was quite something, actually, yes.

TH: It felt like a transformation in the possibilities of the space. Imagine we are standing in front of the grid now. A mirror covers the opposite wall, reflecting us to ourselves against the backdrop of the grid with its measurements now rendered legible. You once suggested: “This grid is the photographic negative of the Alberti screen.” How does this installation relate to the medium of photography and what effect does the viewer’s presence have on it?

MW: Through history, there has always been that artistic plotting of space. I suppose what I’m doing is reversing its terms. I don’t think we’ve ever lost our fascination with transforming actual three-dimensional space into two-dimensional representation. That’s why we’re looking at our screens all the time, and why every so often there’s a short-lived phase of 3D cinema that then goes away, because, actually, I think we’re transfixed by that transformation of three-dimensional to two-dimensional. The photographic image always gives a kind of order to an experience that is otherwise too all-encompassing for us to get a grip on. It’s an abstraction that obviously has some deep appeal to the way we function as human beings. And I suppose, in a funny kind of way, my work has been activated by those people. Maybe I’m reversing what happens at Madame Tussauds. Those who go there are never going to meet these famous people, but they’re used to viewing their flat images, and so I think the fascination of Madame Tussauds is to stare at people in the round, and to be allowed to stare. In a sense, I’ve made an arena for staring at everyday people.

[image14]

TH: In recent years – and here I’m thinking of your 2016 show, ID, at Hauser & Wirth – you have focused on the absent subject through the language of psychoanalysis, developing a restrained, expressive approach; yet it is fair to say that, in 2007, when Muybridge’s grid was first introduced to your practice, you were exploring the way people’s movements through public space are subject to control. State Britain (2007), for instance, features an exact replica of Brian Haw’s Parliament Square protest after it had been forcibly removed by the police, while Zone (2007) – your contribution to Skulptur Projekte Münster – saw you hang a 5km-length of white thread around an area of the city, in the manner of an eruv. [In Jewish custom, an eruv indicates the ritual extension of the domestic sphere on the Sabbath by means of a wire passed over lintels, in order to allow for necessary activities such as carrying]. What kind of “figure” is being proposed or explored in The Human Figure in Space and is there a relation to control?

MW: The grid is like a graph. It’s an archetype. To make that such a tactile and crafted experience is quite a strange thing. Zone (2007) was meant as a retort to the kilometre exclusion zone which the Serious Organised Crime and Police Act of 2005 enacted in British law. [State Britain featured a black line painted on the floor of Tate Britain, indicating the parameter of this “zone”, which, amazingly, cut through the reconstruction of Haw’s illegalised protest.] The eruv had a certain fascination for me because it’s kind of a loophole in the law. At the same time, it’s one of those things that’s very discreet. In a sense, London and Manhattan are eruvin – but unless you know, this kind of thread is invisible to lay people. I thought: “Well, I’m going to decide on this zone.” Even if you encircle an area, that has the ambiguity of which side of that you fall on.

TH: Admission or exclusion … the space in front of the grid is a kind of zone.

MW: And it has its imaginary other half, or its illusory other half, the mirror.

TH: You have previously commented on the grid’s capture of movement as connected to “the propensity of capitalism to measure and modulate”. Of course, evaluating the subject’s interests, desires and patterns of movement is a crucial part of the circulation of capital. (This is social media again). It is somehow harder to imagine this process of performance evaluation playing out on the beachfront at Hastings. How do you envisage this process being playfully undercut through the run of the show by this location?

MW: It’s a complex thing, isn’t it, because they can be rather melancholy places, the English seas. There’s this overriding sense of: “Oh, you’re on holiday, you must have fun. You work five days and now it’s the weekend, now you’re at the beach.” We’re almost given leave to perform a version of ourselves, once we get to the beach. Hastings is home to the largest beach-launched fishing fleet in Europe. It’s elemental, you’re at the sea with the sky and it gives you leave to think about things in a much more fundamental way. I wanted something that has a sense of play. As much as this strong grid, especially in three-dimensions, might feel imprisoning, I think it actually provides a structure that makes you want to see how you activate and how you can be with other people.

TH: The mirror helps with that.

MW: And the video works are, as I say, about people.

[image6]

[image7]

TH: Let’s talk about the other two works in the show. Landscape with the Fall of Icarus (2007), whose title is taken from Pieter Bruegel the Elder, is a video installation that juxtaposes footage sourced from You’ve Been Framed, in which viewers send in humorous home videos. The clips you have selected show people compromised by the forces of gravity, a folly that is, as often happens in your work, exacerbated by the brief loop of the video.

MW: The thing’s shot in 10th time, frame-by-frame slow motion. It alludes to the zoetrope or zoöpraxiscope, the animated versions of Muybridge’s photographic works. Trawling through bloopers on You’ve Been Framed, I quite like the fact that I’d found a grouping in which people were hanging by a thread, for whom gravity was not their friend at a certain point. There’s a very identifiable moment where aspiration and reality meet at a point of maximum embarrassment. The pratfall or the slapstick are about where you see the intention meeting a miscalculation. I quite like the idea of see-sawing the footage back and forth through that moment. The figure on the two ropes across the river, for instance, teeters endlessly – he never falls, but he’s on that edge the whole time.

[image11]

TH: That sense of play is also there in Birdman (2018), a new work made especially for the show. The treatment is very different, as photographic snippets are appended to the wall. How do these two works, which are presented in a separate gallery room, speak to each other?

MW: I felt they had a similar concern. The international Birdman competition has been shared through the years between Worthing and Bognor Regis piers and there’s a cash prize. I’ve followed pictures in the papers of it down the years, but never seem to be around these parts in August when it happens.

TH: But you have collected pictures.

MW: I collected the pictures from various agencies. The two decisions about how they should be presented were that they start from A4 – they don’t need to be any larger – and that the crops were to be determined by retaining as much sky as possible before you hit the edge of the pier, or the beachfront, the buildings or the spectators. So, that was nice. It was a nice way of dealing with the images. There’s something joyous and touching about people participating in this gloriously futile kind of thing. Within that image they are weightless, they’ve attained a different state.

[image13]

TH: It’s quite sublime, somehow.

MW: Yes, yes, indeed.

TH: And there’s a relation to Icarus there.

MW: The most Icarus-like image is a tiny image of a person emerging from the left of the picture. In fact, he’s the only figure who is facing to the right in the entire collection. And he is the most Icarus-like I suppose.

TH: These birdmen certainly present an interesting counterpoint to the grid – a locomotive study that never was.

On Muybridge, Rebecca Solnit has written: “Each study is an astonishing, eerie image of something no one had ever seen before.” I couldn’t help recalling the original fascination felt in response to his study of 1878, The Horse in Motion, which showed for the first time how a horse gallops. The racehorse has featured in your practice, representing an early fascination for you. Are other subjects besides the human figure conjured by the grid? It’s a speculation but, might one envisage a horse in the gallery?

MW: Yes, it would be nice to get the horse in the gallery. Famously, Muybridge’s study was in answer to a wager about whether all four of the galloping horse’s hooves are off the ground. The bigger mystery is how there seems to have been a tacit agreement through the years about how horses should be represented like this [Wallinger demonstrates by sticking his forearms out]. Before Muybridge’s photograph, galloping horses were always represented spread-eagled. The horse was the only means of transport, everyone had a relation with a horse and must have known that this is how they moved, so it is curious that we have to wait until Muybridge to see how a canter goes into a gallop. I mean, I’m sure they knew really, but anyway.

Muybridge was a deeply eccentric man and as much as there’s a sort of rigour about his methodology, there are some very odd and whimsical and bizarre things in there, including chickens being blown to pieces and morbidly obese people. Even naked people appear Victorian in them, but the grid is this thing that still reaches out to us.

TH: Thinking further about the grid’s applications in your practice, in 2011 you collaborated with choreographer Wayne McGregor and composer Mark-Anthony Turnage to make Undance. This reminds me of the choreographic collaboration between Trisha Brown, Robert Rauschenberg and Laurie Anderson, Set and Reset (1983) that was performed at Tate last year. In Undance Muybridge’s grid was activated in a specific way, involving moving image.

MW: I’ve done two dance works now, one with the Royal Ballet and one with Wayne, working with Mark Turnage on both projects. Undance involved a tripartite process: I came up with sufficient ideas, concepts and strictures that were given to Mark to write the music for. He then passed his composition on to Wayne to choreograph from. Richard Serra’s Verblist (1967-68) and Muybridge’s grid were the two starting points. It interested me that Mark could choose specific action verbs, and then Wayne could work from there.

At the same time as Undance, I was working on a show at the Kunstnernes Hus in Oslo in 2010. I had a UN sign pasted outside the building. It kind of struck me that, when you see a UN sign somewhere in the world …

TH: … that it’s also a prefix.

MW: Exactly, and it is very much about our efforts to undo something that has been done. So, that came into it as well.

TH: Undance featured moving images of dancers projected on to the Muybridge grid. How did this work?

MW: In a sense, there were two sets of choreography. There was the choreography of the different movements that we filmed, which were then back-projected, and then Wayne and I developed a response to these moving images. To begin with there was a simple repetition in real space of what was going on in projected space, but then it might shift to the next movement being mirrored. The exercise generated different relations to the image.

TH: Finally, what are we to make of this “mirrored world”, as you refer to it?

MW: I’ve kind of boxed off the room, The Human Figure in Space, so you’ve got this three-dimensional notion of space … it’s not just this running fence. The mirror gives you permission for an experience of presence that’s becoming rarer today. You mentioned photography … We had one of those familiar conversations earlier here at the gallery. When people go to gigs and hold their phones up, they’re instantly distracted. We’ve lost the ability to experience live performance. It’s a cliche, but none of those people at that gig will ever play back that footage. In fact, the press photographer told me he went to see Kate Bush, who was hardline and told people not to record videos. They experienced it as a relief, and I think it is really. These questions kind of feel like a responsibility now, to my experience. I don’t know if The Human Figure in Space is a “cleansing operation”, but it’s a bit like being here: we’ve got permission to be by the sea. We’ve got to get to the end of somewhere, it’s the sublime or whatever. It’s harder to find spaces where you’re given permission to do that in a way.

With this show, I was aiming for something very basic about being a body in a space. The mirror somehow plots exactly where you are, and from just getting the people into space earlier today, it’s striking that, suddenly, everybody looks just so. The photographer asked: “Where do you want people to pose?”, and I just started chatting. It was kind of weird, but they all looked, like, profoundly meant – something quite odd, an odd quality.

TH: Like the exhibits in Madame Tussauds?

MW: Yes exactly, and so to have that mirror there, that’s almost permission not to have the camera and to be able to say: “What is that, what is that relation we’ve got to our image there?” which most people after the opening will possibly experience on their own, with their own reflection.

• Mark Wallinger: The Human Figure in Space is at the Jerwood Gallery, Hastings, until 7 October 2018.