by VERONICA SIMPSON

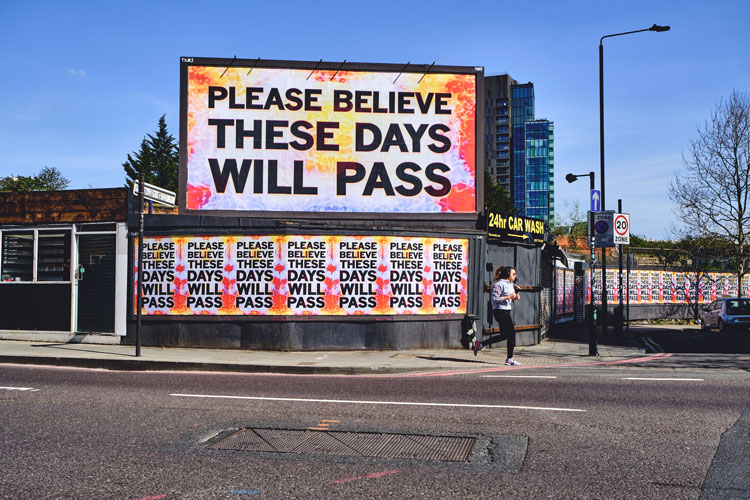

Please Believe These Days Will Pass: if any specific art work has emerged in the foreground of the UK experience of coronavirus, it is this declaration by the artist Mark Titchner, set in upper-case black typography and plastered in multiple formats and scales over billboards, hoardings and bus stops across the country. Part of the creative arts agency Jack Arts’s lockdown-related mission to make good use of surplus advertising space across the UK, it was distributed from late March this year to early May, across 10 cities, animating the daily commute of thousands of key workers and going viral (no pun intended) on social media. Its trajectory of visibility was still in the ascendant in late April, when it emerged on the main noticeboard outside (the recently renamed) Camden Art Centre; the only physically visible manifestation of this edgy north London gallery’s lockdown programme, courtesy of its director, Martin Clark, a major Titchner fan – who promptly posted an image of it to join the thousands already on Instagram.

[image12]

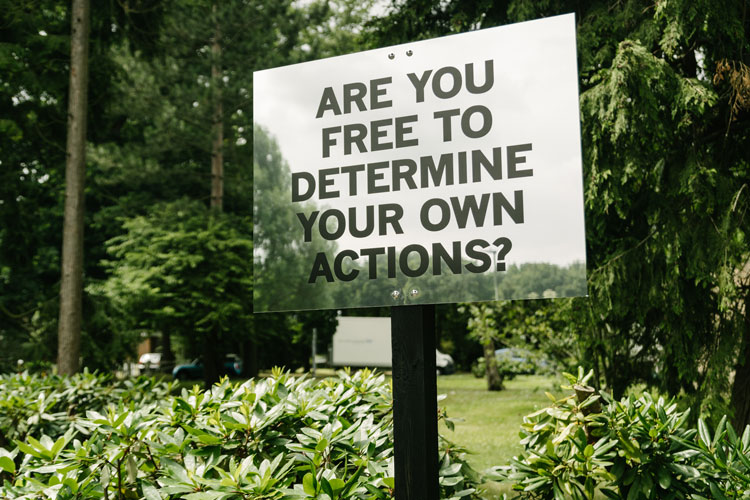

In his text-oriented approach, Titchner (b1973, Luton) may have drawn initial inspiration from Jenny Holzer, but over the last decade he has really made his own mark in the careful, site-specific nature of his responses. And where Holzer’s work is increasingly moving from the street to the gallery, Titchner’s has gone the other way. Most significantly, his works have become a valued and valuable addition to the aesthetic landscape within healthcare environments. For example, he recently lined the pavement-facing border of the Bethlem Royal Hospital, a major psychiatric diagnosis and treatment facility in south-east London, with mirrored placards on which questions - drawn from the questions that form the legal and medical basis by which someone’s mental capacity is judged - are posed to the viewer: “Is your life governed by your own principles?” “Are you free to determine your own actions?” The reflective nature of its background, as well as its placement on a border that physically demarcates the line between free public space and medical confinement, is particularly resonant. Titchner has several healthcare projects coming online this summer, and remains – unusually for artists at this time – busy and visible, although some other projects and events have been postponed or cancelled.

[image6]

All his work involves a careful sifting and measuring of language, along with a rigorous fine-tuning of aesthetic and material response in relation to its context. Holzer’s printed “truisms” (1977-79), using both real and fictional quotes, seemed to presage the 21st century’s endless internet echo-chambers of self-selective opinion. In contrast, Titchner’s attachment to the public realm as display space, and his whittling of essential phrases from a particular linguistic palette– a mixture of religious texts, corporate marketing, governmental bluster and self-help rhetoric – serve to anchor the viewer in place and time, to make us ponder the weight and meaning of each word in their universal and particular contexts, a practice made all the more resonant in the era of fake news.

[image5]

Titchner graduated from Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design in 1995, and was nominated for the Turner Prize in 2006, after his first solo show at Bristol’s Arnolfini. He was showcased at the Venice Biennale in 2007, has had multiple solo exhibitions, including at Peres Projects, Berlin, the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art in Gateshead, Vilma Gold in London and, most recently, at Firstsite gallery in Colchester (2019). His work is in the permanent collections of the Arts Council, the Tate Gallery, the British Council, South London Gallery and the UK Government Art Collection.

Studio International spoke by phone to the artist, at his south London studio.

Veronica Simpson: It seems there has never been a more vital and yet problematic time for art to give voice to a populace, as we undergo the most extraordinary and distressing of collective experiences outside of war. How do you feel about the massive online impact of the Please Believe commission, and how did it come about?

Mark Titchner: That project happened very quickly. At the beginning of March, Jack Arts said: “We’ve got these billboard sites that there is no advertising for.” That work actually goes back to a residency I did in Canada, at the Art Gallery of Ontario, which resulted in an exhibition, Please Believe These Days Will Pass (2012). [The work was responding to ups and downs in Titchner’s life as well as national concern at Toronto’s mayor being caught up in various corruption and substance-abuse scandals]. So, in a way it was much more of a personal message. I did it and forgot about it. Then the Brexit referendum happened in 2016 and an opportunity came up to do a poster, a free giveaway in the European newspaper, post-Brexit results. So, I made a new version of it. As the Coronavirus lockdown happened, people started posting images of that work and were engaging with it all over again. This kind of made the decision for me. And now that work has gone everywhere, all over the media, and I’m being alerted to it from all kinds of sources, because it makes such a good photo background.

It’s interesting that, because I’m now in lockdown in my studio, I haven’t actually seen any in the cities it has appeared in. I’m completely relying on social media images to see it for myself.

[image14]

VS: That must be an intriguing experience, given that your work is very much about being present, and site-specific, in the real world and yet this piece has carved out its main presence in the virtual world.

MT: Most of my work has been in the public realm, but this is a really interesting extension of that. Also, the public realm has morphed into a completely different thing. You see someone coming towards you (under lockdown) and now you need to swerve to give them space. How do you relate to other people in that space?

VS: You said in an interview on the Jack Arts website that you went for a more euphoric background with this version.

MT: It seemed more appropriate, thinking about being stuck inside. When you think about the dream scenario for escape, it is being on a beach looking at the sunset, a Turner-esque moment, so that kind of backdrop seemed more appropriate really. A lot of the works will be going up in very grey, concrete locations, so I wanted the colours to be strong, positive.

[image13]

VS: Compared to many of your works, it seems fairly unambiguous.

MT: Actually, there is something quite complicated about saying “please believe”. Belief is something you can’t force. You can try, but there’s something fundamentally weird about the ambiguity of asking people to believe in something - there’s something slightly desperate about that. We all do feel a bit desperate at the moment … and it’s good that that is also acknowledged.

VS: Given that your work these days often goes into difficult spaces – healthcare settings, for example – or reacts to times of trouble, how do you manage the delicate balance between choosing which words might give voice to a community without offending or disturbing them or others close to that community?

MT: I’ve been doing this a long time, so I’ve got a process that’s very much about reducing things to their essentials … sometimes it ends up being two words. It’s trying to get rid of anything extraneous. It’s like this because I want the grammar to read a certain way. What I try to think about is how the text can be like a tone of voice, and how it makes you feel. I’ve got a pretty poor knowledge of grammar and linguistics and semantics. I aim for something that has the right feeling, certain kinds of words.

[image15]

VS: The Bethlem Mental Health and Justice Project seems to be exploring a particularly landmine-strewn verbal, emotional and political landscape.

MT: This is a Wellcome Trust-funded research project. There are five workstreams and each of those has an artist attached to it. I work with a workstream to do with mental capacity. We are looking at specifically contested cases of mental capacity. It’s something that connects to the Mental Health Act. There might be a situation in someone’s life where they have to make a decision and someone, or a hospital, might say: “We don’t believe this person has the capacity to make this decision for themselves at this time.” It’s quite a far-reaching act. They might have dementia, or suffer from temporary psychosis, or have a head injury. We are looking at judgments and analysing the use of non-legal language. It gets very technical very quickly. So, how to make art with this material? In the end, I thought there were wider issues about autonomy, and issues about the individual and the state, more general questions about capacity and autonomy that could be framed around mental capacity.

Weirdly, the government art collection bought a version of it, which was interesting, because that will eventually get installed in some government department or site. The context for that is super interesting to me. That was almost a dream purpose: for the work to end up actually in … any ministry where people are making decisions about the common good or health or liberty.

VS: Given your current focus on the public realm, have you rejected the gallery system?

MT: It rejected me (laughs). Having said that, I did an exhibition in a gallery last year (Firstsite gallery in Colchester), the first one I had done since 2014, which I was quite nervous about. After it, however, I thought maybe I’ll do more of this. The problem for me is how much of the meaning from the work arises from its site.

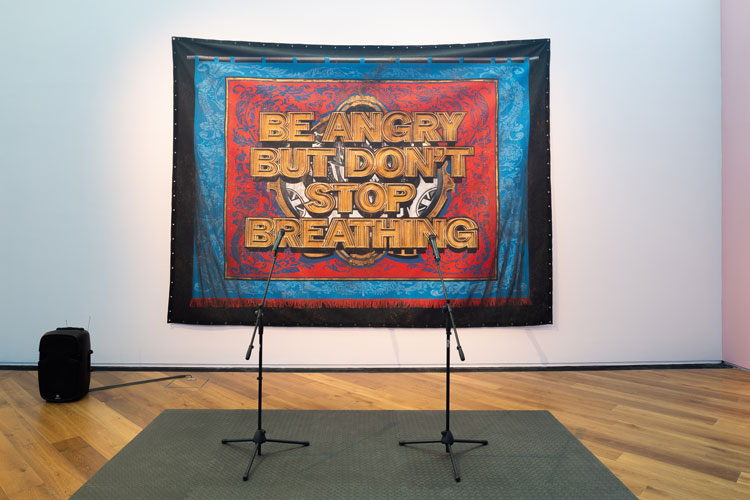

[image7]

When I’ve done works in galleries or museums, I’ve tried to think of those as forms of institutions, making work in a way that can reflect on those spaces. One of the pieces in the show at Firstsite was a work called Be Angry But Don’t Stop Breathing. It’s effectively a stage with an open mic: it opens the gallery up as a space where you can say what you want. I am thinking about the gallery as a public space, or shared space. What I don’t deal with very well is being in the studio and just making stuff. That doesn’t work well for me: I need to know where the work is going.

[image17]

VS: In the public realm, you seem to enjoy going into spaces that are overlooked or utilitarian.

MT: Hospitals, stations and libraries tend to be my pleasure places. It’s those points where we share the experience, but we don’t engage with each other. It’s about being present but not there. It’s a very disembodied version of shared space. It’s a means to an end.

[image19]

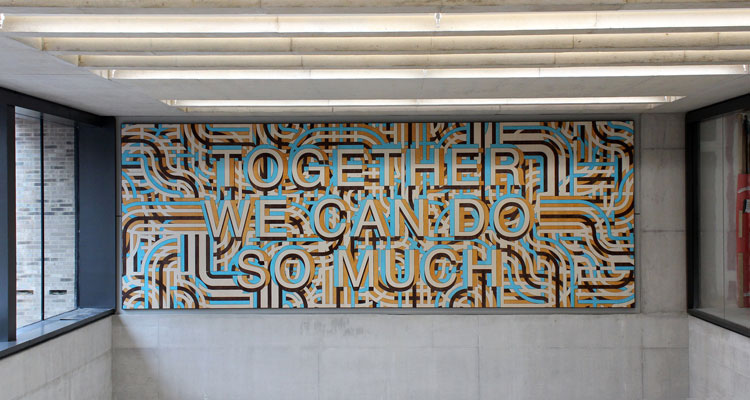

VS: It was great to see the work at the Zayed Centre for Research at Great Ormond Street, last year – Together We Can Do So Much - taken from a quote by Helen Keller.

MT: The Zayed Centre is unique: you don’t find such beautiful spaces in hospitals usually. When I was brought in, it wasn’t quite a functional hospital yet. The challenge is that you try and lead with the artwork, but there’s always this process one goes through of how it will function in a working space. The response has to be very pragmatic - what materials you use, how’s it going to be cleaned, and trying to maintain the art bit through and through can be a struggle.

[image9]

The idea of that piece came from thinking about the function of the building: the vision for it was trying to connect up the various aspects of research and healthcare into a single space that was unique and that would be positive for everyone. That piece was really strange. I’m not saying it was easy, but as soon as I got the brief, I felt like I knew what to do with that one. I didn’t know the Helen Keller quote initially, but I like that it’s from someone who overcame her own health problems.

VS: Where do you begin your research? Do you do a deep dive into a library or do you have favourite sources, favourite writers?

MT: I tend to keep notes as I find them, in my notebooks. Normally, that will be my starting point. I will flip through my last year of notebooks and see if there is anything that gels there even as a starting point. I will do the Google thing, and I’ll make notes when I talk to people, going around a building. Sometimes, you go to people’s workplaces and they’ve got bits of text stuck on the wall. Sometimes, I will just pull books off the shelf in the studio and at home. I do believe in trying to allow things to happen in quite a random way.

[image16]

When it’s a quotation or part of a quotation, it’s to do with the person who might be interesting in the context of that space. I’m making a historical connection between the artwork and where it’s going. Especially with these permanent commissions, that’s something commissioners engage with; they understand the narrative. Telling a story about the work and where it is and why it’s relevant is really important in that period at the beginning, taking ownership of an artwork. Great Ormond Street Hospital has done a great job with all the artwork for that building.

[image8]

For the Helen Keller quote, there’s some space within that phrase, which allows it to not feel like a bossy instruction. There’s a warmth in it. It’s also important the way the text integrates with the imagery. It feels like the text and the image are on the same plane. There’s a real materiality to it, the fact that it’s made of wood.

VS: How do you feel our relationship to words has changed over the last couple of decades. There is so much content out there, of such variable provenance and quality. There is now a fluidity to the way we read and perceive the text, and so little attention paid to whose words they are.

MT: That’s really interesting. If words become so throwaway and there’s so much choice that it doesn’t really matter, it’s an emptying out of language. If that’s what happens, you see it for what it is, you see it as an abstract, empty vessel. That’s the crux of it: trying to expose something about how we relate to the world and it just so happens that the thing we invented for ourselves to mediate that relationship is language. That’s how I ended up working with words: I was messing about with loads of different things that had to do with belief, individuals, self. Once I was able to step back a bit and say all of these things, what connects them is language. Language is how we relate to the world, there’s no separation. We have adhered this material, language, to our experience and that’s what has interested me about it.

VS: Would you agree that the way in which you work – to make words so present and visible - has gained traction perhaps because the words have been devalued?

MT: Absolutely. That goes back to the first time I was using words, during the second Gulf war. The internet was taking off. We were at that point where you had millions of people around the world saying the same thing, but the thing you don’t want to happen happens. These words are empty. And the same with the internet. That feeling then of everything now can coexist and have equal meaning and if all the people in the world are saying it, how do we think about value?

That’s the interesting thing with this latest piece, Please Believe. It emerged at this time based on individual people saying: “This has meaning to me.” The intention when I came up with that text (in 2012) was personal rather than social. At the time, I was just on my own in a strange country with things happening in my life that I needed to get through. We all find ourselves in those situations: you just need to get through this and move on. It was more like something I needed to say to myself. And maybe that’s why it resonates.

.jpg)