Hauser & Wirth, London

2 October – 21 December 2019

by JOE LLOYD

On 11 August 1965, towards the end of a sweltering afternoon in Watts, South Los Angeles, a young African American motorist, Marquette Frye, was pulled over by the California Highway Patrol for drunk driving. The next morning, the neighbourhood erupted in a riot. The reaction was extreme. Areas of LA with a majority black population were placed under curfew and a policy of mass arrest was initiated. Over the course of five days, 16,000 law enforcement officers descended on the area. Shops and cars were looted and burnt, causing over $200m in damage. Thirty-four people lost their lives, 23 of them shot by the police.

Occurring more than a year after the Civil Rights Act officially ended segregation in public places, the Watts Rebellion, as it became known, was a boiling point in the African American struggle for equality. The McCone report on the incident identified underemployment, poor schooling and straitened living conditions as the riot’s cause, and recommended improvements, although these were never implemented. It also contained a map of the neighbourhood speckled with coloured dots – green for destroyed buildings, blue for looted ones and red for deaths.

[image2]

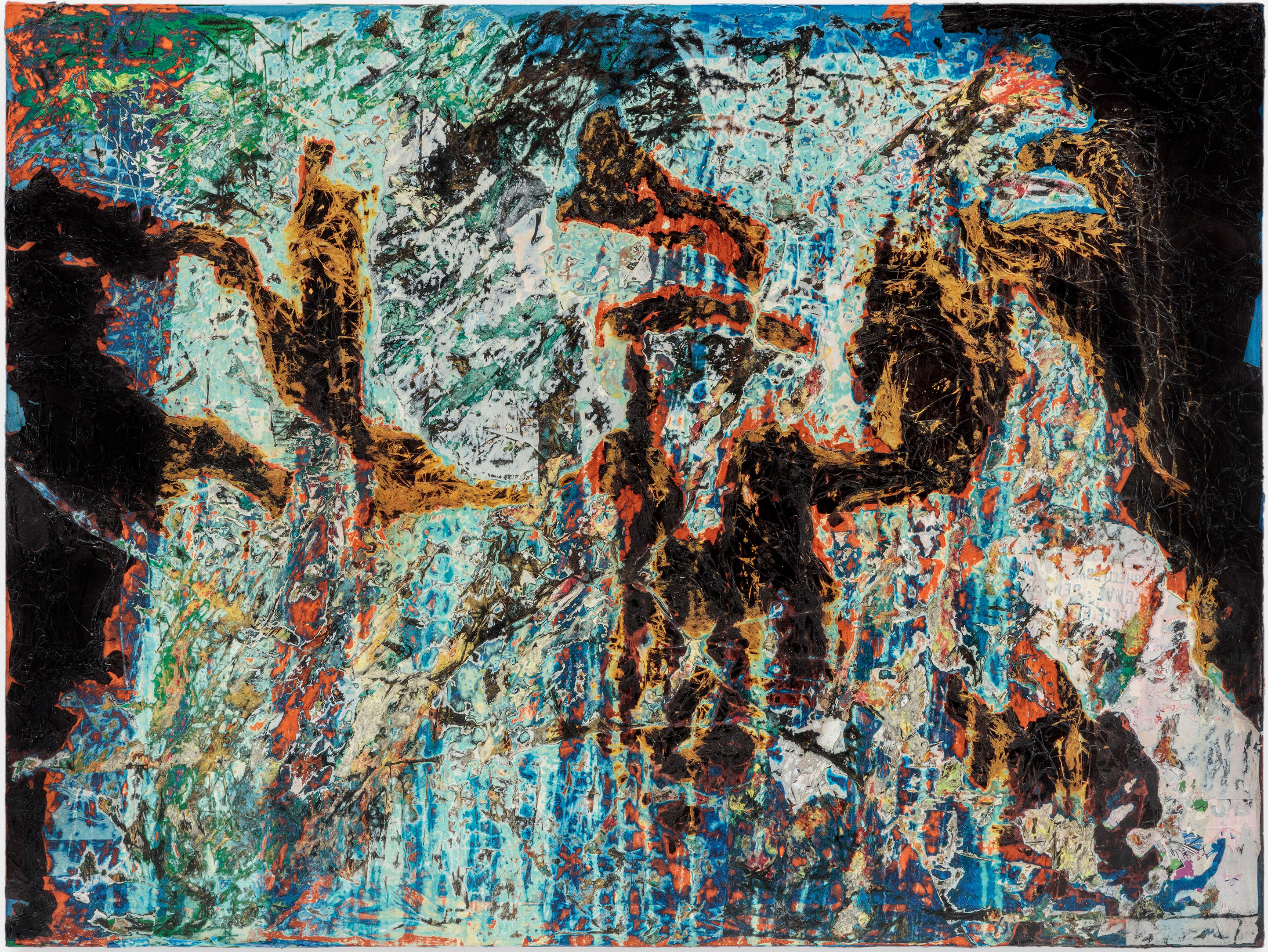

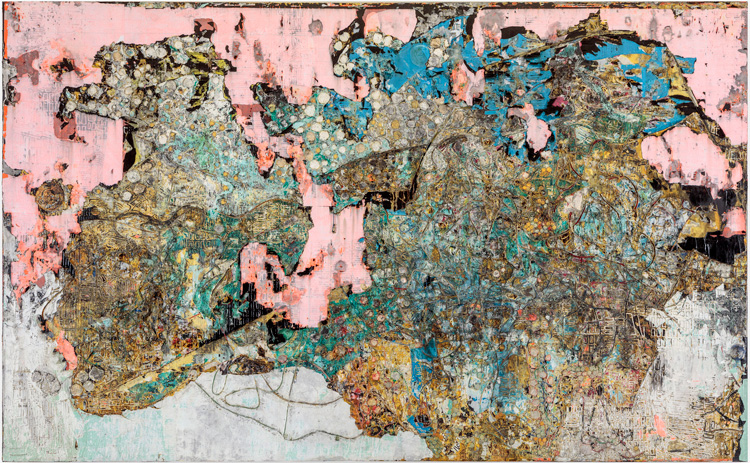

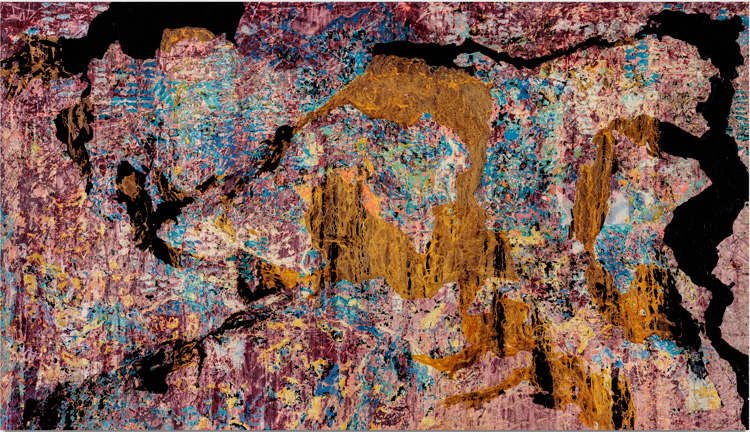

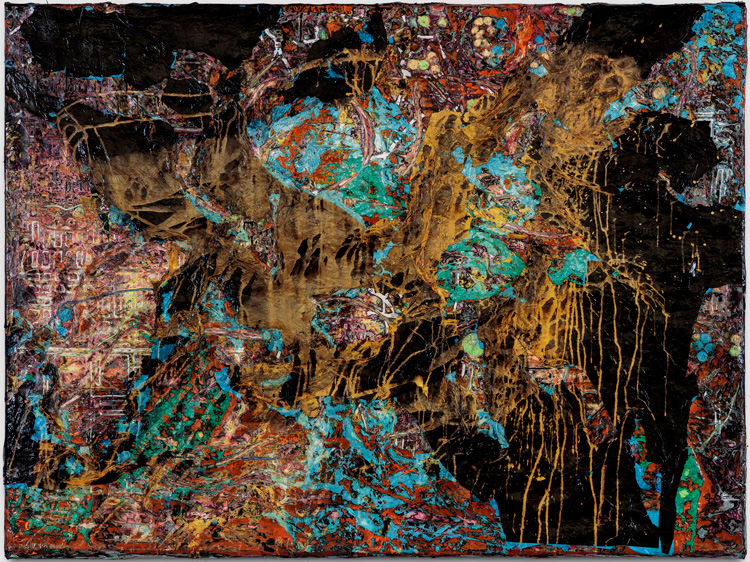

These “hotspots” were the trigger for Cerberus (2018), an almost 14-metre-long work on canvas by the artist Mark Bradford, who was born in Los Angeles in 1961 and continues to live and work there. It forms the eponymous centrepiece of a new exhibition of Bradford’s formidable work at Hauser & Wirth London. It is named for the three-headed hound that guards the gateway to the underworld in Greek mythology, the interstice between the living and the dead. To Bradford, the Watts Rebellion represents a similar place in between, a borderland where conflict might have led to change.

Viewed as a whole, Cerberus has the appearance of a vast action painting, a seething tangle of bubbling colour. Not for nothing has Bradford been called “our [generation’s] Jackson Pollock”. But his opus might perhaps be termed abstracted rather than purely abstract. In places, the map from the McCone report is visible beneath this churning morass, as if viewed from an aerial photograph. “Maps,” said Bradford, in a 2018 interview with the lawyer and activist Anita Hill, “are nothing but the biggest lies on the planet. They’re only the physical manifestation of power.” In Cerberus, he uses riotous eruptions to despoil this imposition of power, turning the city grid into something uncontrollable and uncontainable. The forces of constraint become overwhelmed.

[image5]

Cerberus exists in a well-worn artistic tradition. As well as Pollock, Bradford has cited the Cobra artists as influences, in particular Asger Jorn. But his practice is not simply a revival or extension of mid-century abstraction. “My work exists,” he said at the opening of Cerberus, “between the political and the history of abstract painting.” By building apparently abstract pieces around societal issues, Bradford rejects the abstract expressionist obsession with transcendence and sublimity, where the painting becomes a materialisation of its painter’s unconscious psyche. His art is instead outward-looking, even generous.

It is also not painting in any conventional sense. He sits in the lineage of Robert Rauschenberg, whose Combines brought the debris of everyday life into dialogue with the supposedly more rarefied domain of art. Bradford’s primary medium is paper, often bought from a Home Depot or in bulk from a factory; he has also used posters, newsprint, photographs and texts. He applies these sheets to the canvas in numerous layers, sometimes along with daubs of paint, caulk, shellac and nylon string. Parts of the paper are then removed, using tools that include hoses and sanders as well as his hands, gradually revealing scraps of what lies beneath. There are some parallels here with the artist’s previous job: before attending California Institute of the Arts at the age of 30, Bradford worked in his mother’s hair salon, and there is an echo of that practice in his soaking and trimming.

[image4]

By removing layers, Bradford excavates pieces of the past. In Cerberus, for instance, he tore out the hotspots that prompted the work in the first place, leaving pustule-like splotches in their place. This technique often makes his abstracts appear to be decaying. Gatekeeper (2019) is scarred by a web of depressions made by tearing off ropes from the paper. It looks as if it could collapse at any moment. The Path to the River Belongs to Animals (2019), a smaller work following the same principle, might be on the verge of consuming itself, while the choleric yellow blotches of Frostbite (2019) have an intestinal quality, as if spewed out from within a rotting gut. In the hands of another artist, this putrefying quality might become offputting, even repellent, but Bradford instils his works with a remarkable pulchritude, and an openness to excitement. Decomposition need not be a doleful march to an ending. It could instead provide a gateway to future possibilities.

[image6]

[image7]

Although largely devoted to paintings, Cerberus also contains a new short work on film. Dancing on the Street (2019) sees footage from a performance of the eponymous 1964 hit by Martha and the Vandellas projected from a van on to the backstreets of Watts, past lots that were damaged in the riots. Referencing the urban legend that claims the cities mentioned in the song prophesied the locations of civil rights protests, it turns the stark, ad hoc architecture of contemporary LA into one of Bradford’s canvases swathed in history and myth.

[image8]

Although it takes its subject matter from real and unreal pasts, Cerberus is also an exhibition about our new torrid times, and a US contaminated by racism, police violence, and much more besides. Bradford’s imploding accretions point to unresolved business, to the changes that could still occur. While recording Dancing on the Street, Bradford himself became a small part of Watts’ history. A white police officer drove up and asked him what he was doing driving around the area at night. When Bradford offhandedly responded that he didn’t know, the officer drove away, unable to work out what to do to an African-American man whose behaviour did not accord with the criminality he anticipated. Bradford’s art interrogates and shatters such noxious expectations. His is an abstract art for the present day.