The Dundee Contemporary Arts Centre, Scotland

4 April – 21 June 2015

by CHRISTIANA SPENS

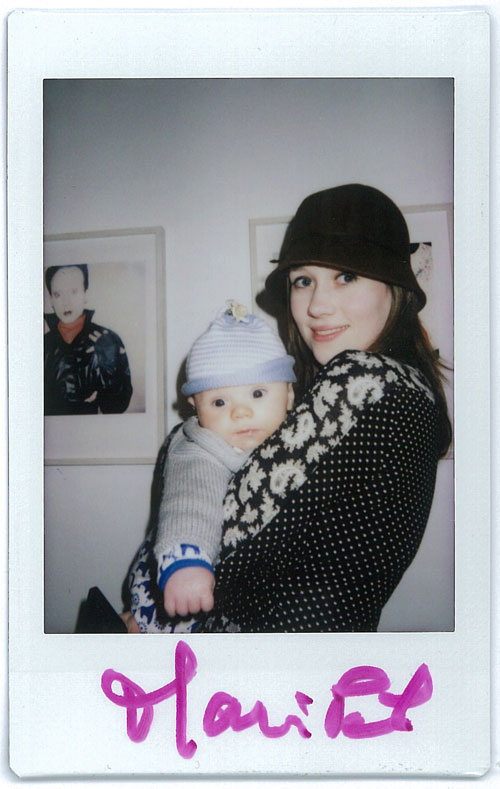

Scotland is often in dire need of glamour, and the photographer and stylist Maripol, joined by two young Glasgow-based artists inspired by her work, has put together a dazzling show at the Dundee Contemporary Arts Centre. The evening before the show opened, I went along with my fiance and our three-month-old baby, Caspian, and was immediately welcomed by a gregarious and charismatic Maripol. Seeing the baby, she came over and took our photo – first with her signature Polaroid camera, and then with a beautiful Leica – and we chatted a little. Our conversation was more about babies than art, but I think I learned more about Maripol through this enchanting brief encounter than I would have done through direct questions about polaroid art (which I’m sure have been asked many times already anyway).

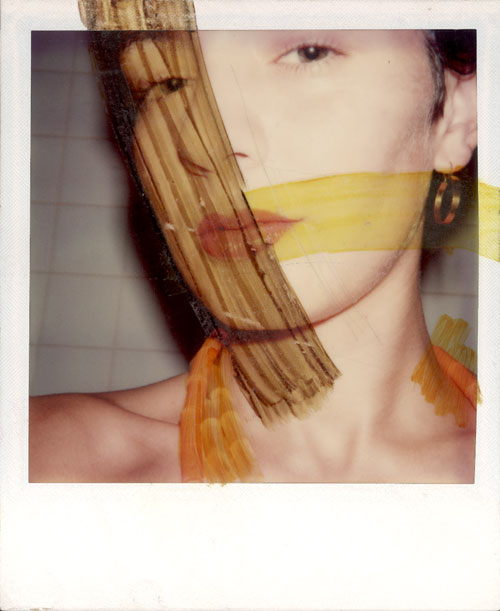

Maripol’s work is very much about moments like these, after all – and in knowing how and when to capture them. Her attitude to us (and she didn’t know I was there to do a review) showcased the way in which she approaches photography and, indeed, life. By noticing, caring and, most of all, by enjoying people and these moments, Maripol has become a wonderful photographer and artist with a legacy of work that is as touching and intriguing as it is glamorous and cool. Maripol herself, who was born in France but went to live in New York in the 70s, is charismatic in a way that is rare and lovely; with her theatrical demeanour and decisive warmth, she embodies the style and character of much of her work. The photographs that line the walls – many Polaroids, of course, as well as larger screen prints of Andy Warhol and Madonna – are portraits defined by their medium as especially momentary and spontaneous. They are brief encounters (even when Maripol knew the subject for years) – with a place, a room, a time of day, as well as the person in its centre. They are bold and confrontational, but in a way that is still playful and original; the subjects face the photographer often head-on and proud; the photographs, in turn, face their audience in this manner.

As a collection, they are also a record of a recent history – the 70s and 80s in New York City, peopled by the now-famous and iconic (such as Jean-Michel Basquiat, Grace Jones and Blondie) as well as some lesser-known figures, captured in their time and their moment, which are in some ways more interesting for being less well known and therefore more intimate. Maripol has a talent for finding moments as well as, I’m sure, creating them. There is an intriguing freshness to the Madonna photos, for instance, taken as the pop star was on the verge of superstardom; there is a weary pride to Warhol’s spectre, in a photo taken towards the end of his life.

As a retrospective (although a condensed one), this show exhibits a whirlwind of a life and practice – shown not only through more than 50 photographs, but also an array of clothes and jewellery she designed, from ethereal silk shirts printed with her Polaroid images to a customised leather bomber jacket, and from rubber bracelets to mementos of her time styling Madonna’s early image and Blondie’s Parallel Lines album cover. Her recent clothing line, in collaboration with French fashion house Each x Other, is also on show in an accessible and playful manner – on a rail by the photographs, blurring the line between an art exhibition and the backstage of a fashion show.

Through the connected work of artists Zoe Williams and Clare Stephenson, furthermore, we understand that this is a legacy that lingers. Stephenson’s sculptural installations – newly commissioned versions of her Venetian Cocktail Glassesand Martini Bikinisseries, and Williams’s video work Drench, both show how Maripol’s style and the mythology her Polaroids and designs create, have influenced a younger generation. As Graham Domke, the DCA’s exhibitions curator explains: “Maripol is such a vital force – an artist who has shifted between many media – so it is inspiring to bring her to the DCA where I know her work will be appreciated by new generations of artists. Her involvement in the cultural melting pot of New York was revelatory and we are excited about presenting her work in Dundee, particularly given the city’s new status as Unesco City of Design. Williams and Stephenson are exceptional Scotland-based artists who are both carving out fascinating careers. All three artists share a fascination with decadence and freedom.”

In the opening as well as the work, however, Maripol is at the centre of this brilliant storm, connecting times, places and people, and creating something – je ne sais quoi – that lights up, persists and enlivens. Some say that fashion and art such as this is superficial or unnecessary, and that is always an easy criticism to make, but as with Romantic poetry and visionary novels, there is something difficult to define but no less necessary about a form of art that is focused on the good things in life – interesting encounters, beauty and the fast flicker of time remembered and experienced in the staccato of photographs and soundtracks.

As the Polaroid of Caspian and me developed – as Maripol shook the photo and our images emerged – she told me about her own son as a baby, about being a mother; when she had signed her name in pink on the white border below the photo, she took Caspian in her arms and said hello as he smiled and gazed in wonder. A photograph is a meeting, an encounter like this – a memento of life and love, at times – and as Maripol went back into the whirlwind of the opening I gained some insight into the meaning of joie de vivreand the genuine warmth behind her practice.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)