Dundee Contemporary Arts, Scotland

8 December 2018 – 24 February 2019

by CHRISTIANA SPENS

“Love and abuse cannot co-exist” is the message at the centre of Margaret Salmon’s compelling new exhibition, which uses film and installation to communicate a form of love and intimacy often dismissed by mainstream media representations. But how does film – and an audience – affect that intimacy? How do we react to others’ private moments of pleasure and love? How do we feel about moments and memories, and the loss they imply? The new exhibition, Hole, at Dundee Contemporary Arts (DCA) dares to delve into these questions.

[image2]

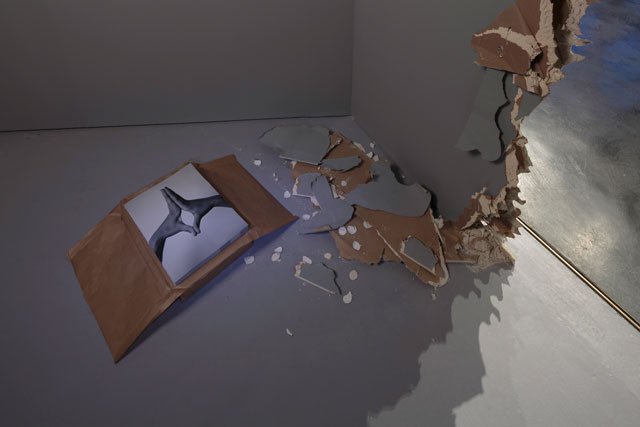

In the recently refurbished DCA, freshly painted in red and grey and containing the seasonal hubbub of visitors, lights and decorations, the large hole in the wall at the far end, surrounded by rubble and guarded by a quietly seated member of staff, looks rather incongruous. Is work ongoing? Has a drunken reveller crashed into it and created this person-sized void? As I approach, the gallery assistant smiles calmly; there is a stack of exhibition guides neatly displayed to the right. Hole begins here, with a void and a smile, and a warm darkness beyond.

[image3]

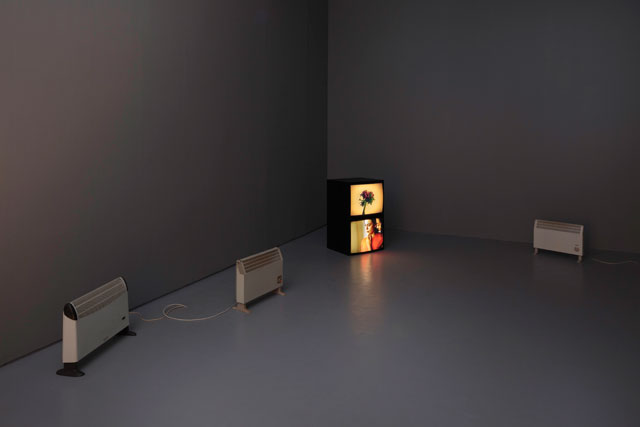

Inside the exhibition, I adjust to the warmth of the gallery, subtly created with electric heaters placed between two monitors and the rubble. The screens, stacked in the corner of the room, show a two-channel film on loop – I You Me We Us – with visual representations of warmth, tenderness and friendship. Hands touch and become entwined, before disentangling; a palm brushes against a face tenderly. Repeated images of written words, shapes and an art deco figure in a stained-glass window create an intimate little world of private signs, shared between two people and screens. The films, in fact, switch screens, so naturally that it is almost imperceptible, as if the screens are two human perspectives sharing a singular experience, language and love.

[image7]

As visitors stand, there is also a sense of being on the precipice between intimacy and the world outside, given the hole in the wall and its rubble, and distant noises from outside. There is a tension in this, and in the way that people stand rather than relax into a seat; a sense of potential intimacy and trust but also a sort of nervousness and restlessness. The degree to which we are partaking in a form of voyeurism seems unclear; the sense, too, to which the people in the film are natural or self-conscious, real or acting, also remains something of a mystery. Thoughts about intimacy and performance are raised, inevitably: how do we communicate love and sensuality, to each other and to everyone else? Who is watching and how does that affect how we behave? The screens here seem a little like those that security personnel monitor; there is a feeling of both authenticity and anxiety in this subtle dynamic between the audience and the people filmed.

[image6]

Around the corner, three black-and-white short sequences form Two, shot on slow, languorous 16mm film. Each film shows a couple – one gay, one straight, one non-binary – kissing, touching, having sex, sleeping side by side – in sequences that capture a range of activities in structures that seem nevertheless parallel and entangled. As the individuals in each film embrace one another to the point of a sublime singularity, so do the three films together. While the scenes may not be choreographed exactly (they seem natural), their presentation together certainly is. Like three couples dancing on stage to the same song, they seem to embody a sort of physical harmonisation, both natural and organised.

[image4]

Rather than music though, we hear a sound work – Your Breath, So Close – which combines recordings of human breath, some of the audio recorded while making Two, and spoken excerpts from feminist theorist Bell Hooks’ book All About Love, which presents a “new ethic for intimacy, care and community” that reacts against and builds from existing ideas of romantic love. “Love and abuse cannot co-exist,” we hear, as two women embrace. Here, instead, is a couple who care about one another, who make each other physically happy and safe. As Salmon has said of Two: “This is an attempt to trace a physical manifestation of love between committed partners, through the mediation of my camera. It’s a simple, intuitive account of the collaboration between myself and the people in the work, and is a celebration of connection and intimacy between caring bodies, as seen through a woman’s camera lens.”

[image5]

How do these images of love and affection make their viewers feel, though? In collaborating with these couples and presenting these films, Salmon offers up a new romantic ideal – one that is comforting and moving, but also melancholic. There is a sense of these tender moments being haunted by the world that they have escaped from, by the intrusive darkness around us and the literal hole in the wall. These couples are on a screen – both everyday (in the films’ contexts) and yet untouchable. They are anonymous and unknowable. Their lives and the contexts of their love – their stories – remain unknown to their audience.

To some people, that lack of context will contribute to the sense of purity and escapism that these films offer; to others, there may be some sense of detachment or even loss. They are like disembodied memories – someone else’s memories, and yet, in lacking context, also reminding us of our own. As Susan Sontag wrote: “All photographs are memento mori. To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s (or thing’s) mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt.”1

[image8]

Indeed, when I watch the films, I am overcome by a sort of sadness that I cannot place at first. Am I sad that other people are so happy, but that I, in being in the darkened audience, am alienated by detachment from that joy? Am I melancholic because the happy times have already ended? Am I reminded of my own memories, recognising intimacy that has already been lost? Am I uncomfortable being a viewer (and not in the intimate world itself)?

In truth, I think that in watching these films, it dawns on me the extent to which we are all audience members in our own lives, in our own relationships and romances, other than in these truly free, intimate moments, where fleetingly we forget ourselves, our perspectives, our lives – and the realities of relationships. “La petit mort”, as the French term the act of sex, of love. The little death. Perhaps there is nothing better suited to photography, and the attempt to capture an already lost moment with a lens.

Hole is a stirring and heartbreaking work. I left the room sad, and then I went back again, and again, until I could go back no more. Salmon may have presented a form of intimacy that is more loving and tender than many mainstream representations of sex and romance, but do not be fooled – that authenticity does not remove a sense of pain and loss. Love and abuse may not co-exist, in these films, but love and pain are inevitably entwined, just as life and death dance together in the capturing of a given moment by photograph (or film).

To experience Hole is to edge closer to the experience of love, but although the couples in the films highlight the pleasurable aspects of that, as a viewer, the tense interactions with voyeurism, detachment, memory and loss are entangled, too. That is not a criticism of the work, but rather an observation that in communicating something true and authentic about the experience of intimacy, the work opens up a world of contradictions and complexities that cannot be divorced from love and sex, even at its most pleasurable.

Reference

1. On Photography by Susan Sontag, published by Penguin Books, NY: 1977, page 15.