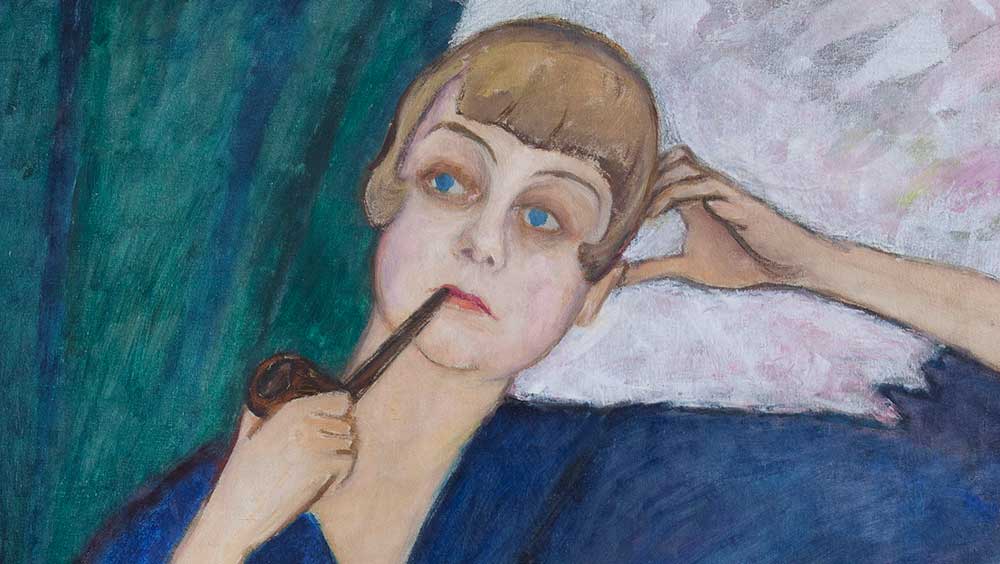

Gabriele Münter, Portrait of Anna Roslund, 1917 (detail). Oil on canvas, 94 x 68 cm. Leicester Museums & Galleries. © DACS 2022.

Royal Academy of Arts, London

12 November 2022 – 12 February 2023

by BETH WILLIAMSON

Making Modernism is a jewel of an exhibition. Built around the work of four female artists working in Germany in the early 20th century, this show excels in its intelligent handling of works by Paula Modersohn-Becker (1876-1907), Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945), Gabriele Münter (1877-1962) and Marianne Werefkin (1860-1938). There are additional works by Erma Bossi (1875-1952), Ottilie Reylaender (1882-1965) and Jacoba van Heemskerck (1876-1923), but Modersohn-Becker and Kollwitz are the stars here, with Münter and Werefkin providing strong parallels. These are the paintings many of us have seen in art books or on websites, but rarely face to face in a gallery. Many are astonishingly intimate in their approach, sharing the deep joy of maternal love or the agony of losing a child. Still, there is much more to this show than motherhood. These are women in Germany exploring and sharing the modern world and their experience of it. Men are present in some of these images, but they are very much in the background as the focus is on the artists’ experience of the modern world, whether that is motherhood, friendships, city life or travels in the countryside.

Erma Bossi, Portrait of Marianne Werefkin, c1910. Oil on cardboard, 71.6 x 58 cm. Gabriele Munter- und Johannes Eichner-Stiftung, Munich. © The Estate of Erma Bossi.

The exhibition is organised around four main themes – Ourselves and Others, The Century of the Child, Sites of Intimacy, and City and Country – that help to focus our attention on what was important to these women. Their portraits and self-portraits reveal a great deal about their place in society, how they increasingly resisted existing ideals of feminine roles that limited them to the home and built important and sustaining artistic networks that were significant as modernism emerged in Germany. We can see this particularly in their portraits of each other, including Bossi’s Portrait of Marianne Werefkin (1910) and Münter’s Portrait of Anna Roslund (1917), the latter being one of the few paintings in this exhibition to come from a collection in the UK. Werefkin’s Twins (1909) is an astonishingly acerbic painting while Kollwitz’s Woman with Dead Child (1903) depicts the silent agony of loss. Modersohn-Becker’s Girl with Child (1902) and Münter’s Portrait of a Boy (Willi Blab) (1908/09) both show something of the gendered societal expectations of their time, even from childhood.

Marianne Werefkin, Twins, 1909. Tempera on paper, 27.5 x 36.5 cm. Fondazione Marianne Werefkin, Museo Comunale d'Arte Moderna, Ascona.

There is nothing sentimental about the children depicted in this exhibition. Their gestures, expressions and countenance reveal their anguish and anxiety, as might be expected at this time in German, and world, history. Emotions are conflicted not only in the children depicted here, but in their artist mothers who are caught between societal expectations of motherhood and their desires to work and advance in their artistic careers. This was also a time when attitudes to children changed, with the publication in 1900 of the influential book The Century of the Child by the Swedish feminist Ellen Key, which posited a child-centred approach to parenting and education.

Käthe Kollwitz, Woman with Dead Child, 1903. Etching on paper, 42.4 x 48.6 cm. © Käthe Kollwitz Museum Köln.

The central gallery space in this exhibition is devoted to the theme of intimacy and sets Modersohn-Becker’s paintings in dialogue with Kollwitz’s powerful drawings and prints. The conversations sparked between works in this small space are potent enough to stop us in our tracks and hold us in the space. Visitors linger here because, I think, they cannot quite comprehend what they are seeing. Modersohn-Becker’s Infant with Mother’s Hand (c1903) conveys the tenderness of the child’s mother through a simple touch while her Baby, Breastfeeding (c1904) shows the sheer dependence of the baby, its utter helplessness. In her full-length nude self-portraits, Modersohn-Becker rejects the male eroticising gaze. At the same time, she often shows herself holding fruit or flowers, aligning with the tropes of northern Renaissance painters such as Lucas Cranach the Elder and Albrecht Dürer, albeit using a pared-back modernist aesthetic. Kollwitz’s prints and drawings in this room, including examples of her “Secreta” or secret drawings (never shown or sold during her lifetime), are simply arresting. The texture and tactility of these images means that our experience of them is bodily as well as visual. We are drawn to the embrace in these images and can almost feel it.

Gabriele Münter, Still-life on the Tram (After Shopping), c1912. Oil on cardboard, 50.2 x 34.3 cm. Gabriele Münter- und Johannes Eichner-Stiftung, Munich. © DACS 2022.

Urban life and rural refuges are another theme for this exhibition. These women show the modern city through its activity at the circus, the opera and the cafe in a similar way to their male counterparts. However, as can been seen in paintings such as Werefkin’s At the Café (1909), women are in the foreground in such images. There is wit in works such as Munter’s Still-life on the Tram (After Shopping) (c1912) and the beauty of the natural world is celebrated in works such as Modersohn-Becker’s Landscape with Windblown Trees (1900).

The role of the still life in the work of these artists becomes a vehicle for meditation so that compositions such as Münter’s Apples on the Wall (1908) and Modersohn-Becker’s Still-life with Blue Casket (1907) divert from the academic still-life to a modernist exploration of form, colour and space, often replete with spiritual meaning. No longer a minor genre of art, the still-life becomes a means of reflection, of stepping back from the everyday responsibilities of modern life for a moment.

Paula Modersohn-Becker, Girl with Child, 1902. Oil on cardboard, 45.3 x 50.5 cm. Kunstmuseum Den Haag, The Hague.

It is astonishing that the exhibition’s curators achieved so much with just 67 paintings and works on paper in three small galleries within the Royal Academy. This is a rather brilliant exposition of the work of these artists, the first major UK exhibition of its kind, and many of the works have never before been exhibited in this country. Yet, I am not alone in suggesting that these women have surely still been consigned to a much smaller space than they deserve. There is still a great deal of work to be done in restoring these artists to their rightful place in histories of art.