Serizawa: Master of Japanese Textile Design

Japan Society, New York

9 October 2009–17 January 2010

by CINDI Di MARZO

Serizawa’s expertly crafted and aesthetically pleasing works reflect cherished, traditional Japanese craft values, yet they transcend the term ‘craft’ in the traditional sense. As a result, they have attracted considerable attention in Japan and abroad, particularly after Serizawa was designated as a Living National Treasure.2 For example, his bold stencil-dyed ‘Seabream’ kimono from 1964, a symmetrical patterning of fish against a vibrant red background on tsumugi-weave silk, impressed Polish-French painter Balthus (1908–2001) on his 1965 visit to the artist and led to a 1976 Serizawa exhibit at the Grand Palaise in Paris. Two years later, San Diego State University invited Serizawa to teach a summer seminar and organized exhibits of his work in San Diego, Los Angeles and Vancouver. Exhibitions and honors followed in Japan, France and the US Acknowledging Serizaw’s role in the folk craft movement and post-War World II economic revival, in 1989 the Shizuoka Municipal Serizawa Keisuke Art and Craft Museum opened on the Tohoku Fukushi University campus in the artist's hometown. Serizawa’s son, a professor at the university, served as museum director until his death in 2006. Following the artist’s death in 1984, exhibits of varying sizes have been staged: in 1979 at the Mingei International Museum in La Jolla, California; in 2001 at the Royal Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh; and in 2006–2007 at the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg.

Now New Yorkers and visitors to the city can view the first US survey of Serizawa’s career. According to Japan Society’s Joe Earle, vice-president and director of the Japan Society Gallery where the exhibit is staged, a comprehensive consideration of the artist’s work is long overdue. Scheduled in the gallery until early January 2010, Serizawa: Master of Japanese Textile Design will introduce this prominent figure in the Japanese folk craft (mingei) movement to hundreds of people who will come away with a high regard for the textile legend equal to that held by artists and craftsmen, mingei theorists, collectors and students who knew him.

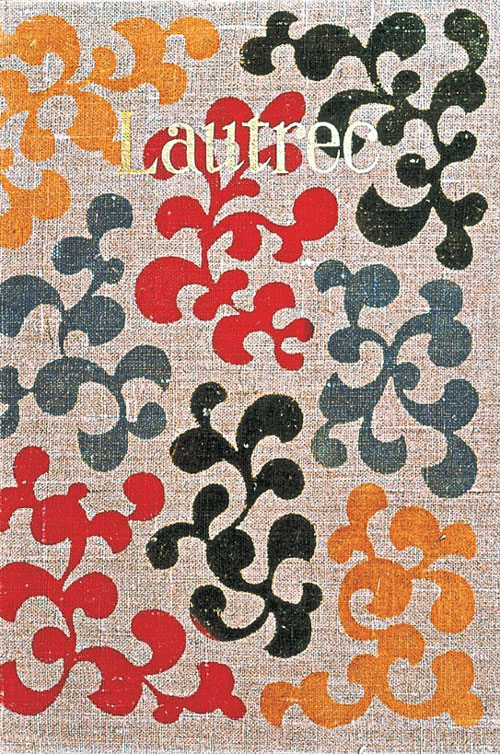

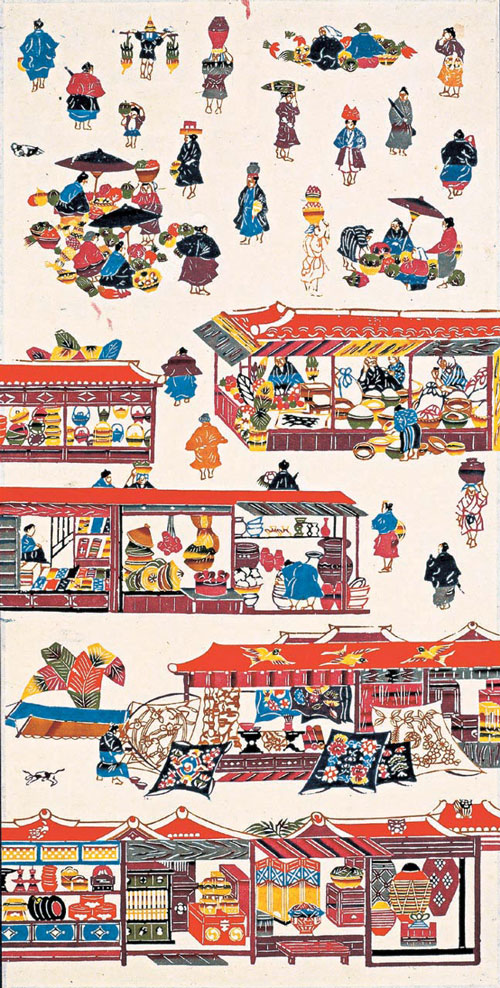

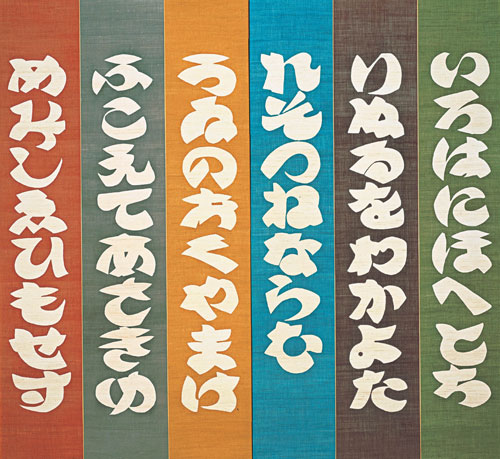

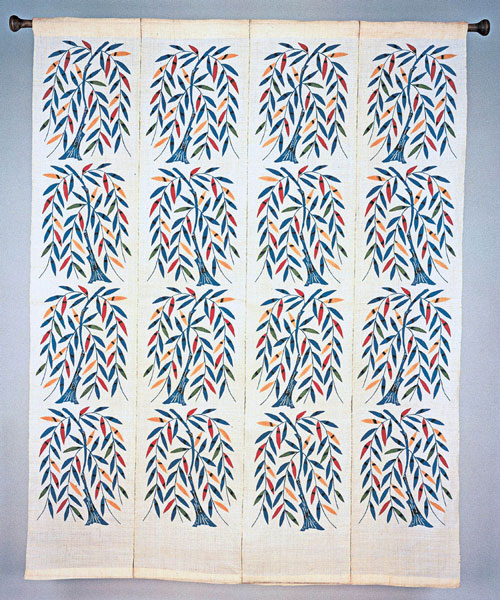

Before viewing the 100 works in the show, those unfamiliar with the mingei (‘people’s crafts’) movement that began in Japan during the late 1920s and 1930s are advised to read up on the subject. A bit of background is needed to fully appreciate Serizawa’s place in mingei's revival of traditional handicrafts made to enrich the daily lives of people at all levels of society. While the exhibition catalogue includes contextual essays, the wall text provides an abbreviated form that can only scratch the surface. But even without prior study, visitors will enjoy the colors, textures and literary allusions found in Serizawa’s scrolls, wall hangings, kimonos, obi, noren (doorway curtains), books and large folding screens. The artist may have embraced mingei values, yet was never absorbed by it, and he never aspired to the nameless artisan ideal mingei promoted. Rather, he pursued synthesis, as seen in his clever arrangements of traditional Japanese alphabet syllables and Chinese characters, witty renderings of Western classics (Aesop’s Fables, Don Quixote), indisputably modern takes on traditional Asian themes (Japanese books and scrolls, a papermaking village, an Okinawan market), and bold graphics drawing on his successful career in commercial and industrial art. Having designed products for a wide range of uses, Serizawa brought to his work insights, perspectives and a market-savvy alien to his other advocats of mingei.

Rooted in colonial Korea, mingei helped Japan modernize between the two world wars. Middle-class Japanese artists and collectors found a treasure trove in traditional Korean crafts, while aesthetic theorists created a vision of beauty reaching beyond the visual arts to encompass culture and society. Mingei activists spread their mission to the press and governmental agencies through department stores displays and grassroots initiatives. In 1927, Serizawa experienced his first life-changing event when he met founding mingei philosopher Yanagi Muneyoshi (1889–1961). In her essay for the exhibition catalogue, Kim Brandt, a specialist in modern Japanese history, identifies Serizawa among Yanagi's ‘inner circle’, along with potters Hamada Shoji, Kawai Kanjiro, Bernard Leach and Tomimoto Kenkichi; printmaker Munakata Shiko; and lacquerer/woodworker Kuroda Tasuaki.3 Recognizing that Serizawa and Yanagi shared an interest in the ema (small painted wooden plaques) offered at Shinto shrines, a wealthy collector brought them together in Serizawa’s Shizuoka studio, southwest of Tokyo. Brandt also notes that at this time, Serizawa was in his early thirties and had spent years as a designer and production supervisor. He had won national awards for his posters, advertisements and shugei (hobby-craft).

Certain elements of Serizawa’s early biography forecast a resonance with mingei values; born into a family of cloth merchants, Serizawa was, literally, born into textiles. His grandfather was a calligrapher and, likely, the inspiration behind Serizawa’s subsequent use of Japanese symbols and Chinese letters in his designs. Early in life, he began painting and aspired to the fine arts. When his family’s financial setbacks dashed these hopes, he enrolled at a design college. After graduating, he began teaching and found work as a commercial designer, two pursuits that followed him for the rest of his life. Brandt concisely targets the ways in which Serizawa’s vision merged with and diverged from Yanagi's philosophy: ‘Serizawa’s admiration for older, indigenous East Asian handicrafts does not seem to have extended to a complete acceptance of the anti-modernist, anti-industrial principles articulated and preached by Yanagi in his emerging handicrafts theory.’ Brandt suggests that Serizawa became a mysterious figure among prominent mingei artists precisely because he remained silent on own views. Despite publishing volumes of stencil designs, Serizawa did not record his aesthetics with words. His personal art collection (African masks, Japanese craft objects and toys, Okinawan textiles and Korean paintings) and his works are more accurate windows into Serizawa’s intent than any words he might have uttered.

From the time he encountered Okinawan bingata, its impact on him became evident. While overt influences are less apparent in works dating from the mid 1950s, after his Living National Treasure designation, Okinawa and the paradise it represented for him seemed never distant. In her catalogue essay, textile scholar Amanda Mayer Stinchecum details the process of bingata paste-resist dyeing technique and distinguishes it from others with which Serizawa would have been familiar.4 Okinawan textile craftsmen participated in every stage, from sketching images and patterns, cutting stencils, applying resist design and dyeing cloth. Earle explains that when Serizawa revived katazome, the traditional Japanese stencilling technique, he applied one of Yanagi’s critical ideas by carrying out or supervising each production stage. The honor bestowed upon Serizawa by the Japanese government included recognition of his innovation, and a new term was coined for his process: kataezome. In hindsight, Serizawa achieved a perfect marriage of art and craft, injecting his personal aesthetic and capitalising on the capacity for mass production inherent in mingei methods. Japanese workers may not be able to afford a large tsumugi-weave silk screen stencilled with a mandala of the four seasons or a silk gauze kimono stencilled with fishing boats, but they could display a copy of Serizawa’s inexpensive calendars, issued every year since the end of World War II. In fact, they still can.5 In his catalogue essay, art historian Hiroshi Mizuo says that Serizawa regarded stencilling as the most authentic dyeing technique and favored it because it ‘helped filter out any tendency toward arbitrariness or undue individuality on the part of its practitioners’. That Serizawa approached his work with a fine artist’s sensibilities and made singular works of great beauty within this context ensures that he will remain an elusive figure in mingei history.

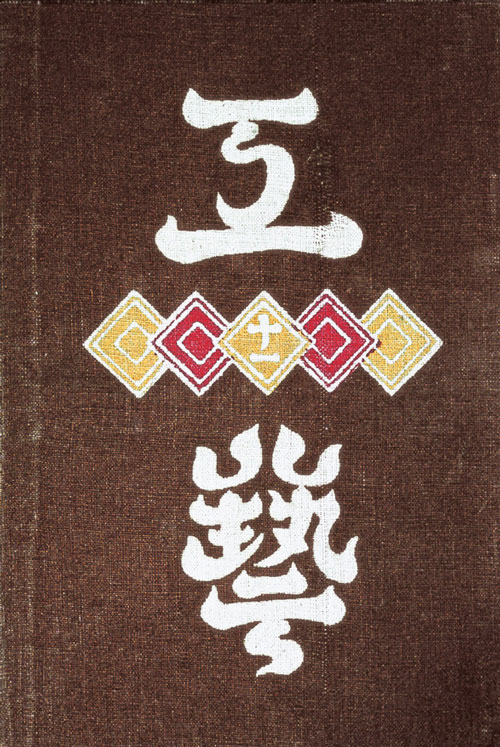

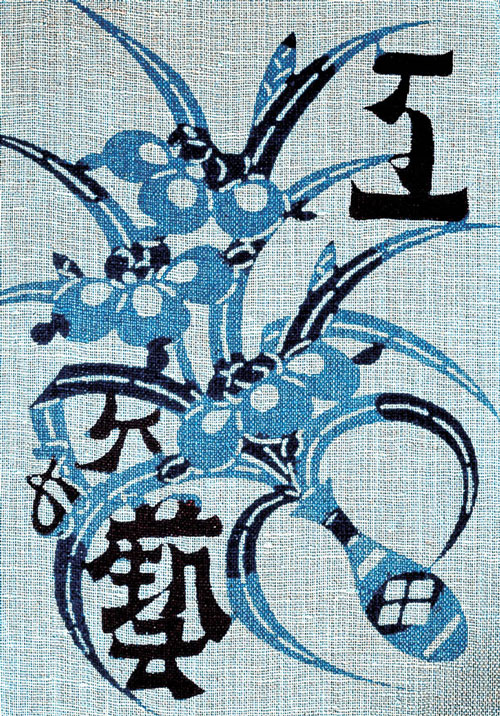

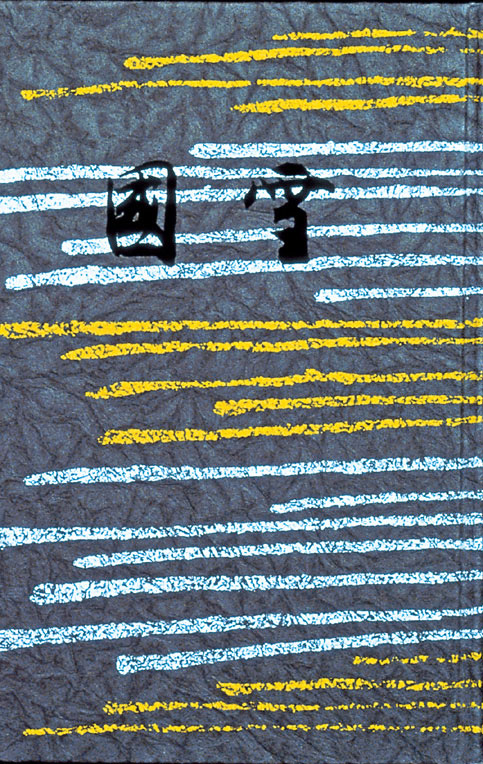

Similarly, the mingei movement neatly dovetailed with Serizawa’s interest in book, periodical and advertising design. Yanagi commissioned from Serizawa textile covers and wrappers for Yanagi's Kogei (‘craft’) magazine.6 Not surprisingly, Serizawa took an unusual approach, stencilling text as well as image. Included in this exhibit, copies of these covers and wrappers are joined by witty interior illustrations for Ehon Don Kohote (A Don Quixote Picture Book), commissioned by a Boston collector; covers for Shikiba Ryuzaburo’s Van Hohho no shogai to seishinbyo (Van Gogh’s Life and Mental Illness); Takeda Taijun’s Shi-san-mei (The Tale of a Chinese Woman Ninja); and two works by Yanagi. (One of the last exhibited works, a stencil-dyed portrait of Yanagi on painted paper made by Serizawa circa 1962 soon after Yanagi’s death, shows a stern figure with piercing eyes covered by a dense, multicoloured halo.)

Apparently, Serizawa was an energetic figure; collecting, teaching and producing illustrations and advertisements, and always seeking more time to devote to his art. After his Living National Treasure designation, he rented a home/studio in Tsumura, travelling nearly two hours from Tokyo by train to ensure his privacy. From this time, he adopted an intensified design strategy informed by simplicity and abstraction. Considering the entire range of his production, though, certain elements remain constant and define Serizawa’s legacy. As they walk through the exhibit in Japan Society’s elegant gallery space, each room a tranquil oasis, visitors will see images echoing Celtic, Arabic, Indian and Native American visual culture along with Japanese, Chinese and Korean; portraits of daily life among common people stencilled on luxurious kimonos and folding screens; scenes of craftsmen at work decorating objects meant for modern homes; and boldly modern graphics applied to fabrics with time-honored techniques. Serizawa spent years creating in the Dragon Palace, his personal paradise, to emerge a master of synthesis.

References

1. ‘The Textile Art of Serizawa Keisuke’ by Joe Early, Orientations: The Magazine for Collectors and Connoisseurs of Asian Art (Japan Society, September 2009). Vice president and director of Japan Society's gallery, Earle organized Serizawa: Master of Japanese Textile Design and edited the accompanying catalogue.

2. Bestowed by the government-appointed Committee for the Preservation of Cultural Properties, the official designation of this honor is ‘Holder of an Important Intangible Cultural Property’.

3. Edited by Joe Earle and published in association with Yale University Press, the full-colour, paperback exhibition catalogue reproduces 100 exhibited works captioned with details of each and explanatory text; a chronology of the artist’s life; a four-page illustrated guide to Serizawa’s stencilling technique, kataezome; and essays considering Serizawa’s work from different perspectives by art historian Hiroshi Mizuo, textile scholars Terry Satsuki Milhaupt and Amanda Mayer Stinchecum, Duke University Associate Professor Kim Brandt, Brandeis University Assistant Professor of East Asian Literature and Culture Matthew Fraleigh, and Serizawa scholar Shukuko Hamada.

4. See, ‘The Textile Art of Serizawa’ by Joe Earle, Orientations.

5. Early copies of Serizawa’s collectible calendars were popular with the wives of US Army officers stationed in Japan.

6. After Yanagi and his colleagues organized the Nihon Mingei Kyokai (Japan Folk Art Association), he founded Kogei (1931) and established a folk art museum in Tokyo (1936).