Tate Modern, London

30 July 2018 – 14 July 2019

by EMILY SPICER

Magic realism – the combination of fantasy and real life, the dreamlike and the strange, the exuberant and the angst-ridden – was the product of one of the most extraordinary periods in history. It swung from postwar grief to a brief time of artistic liberty and hope, before the depression hit, giving Hitler the leg up he needed to become chancellor in 1933. If you were ever in any doubt that art is a barometer of the society that produces it, let this extraordinary group of artists settle your mind on the subject.

[image5]

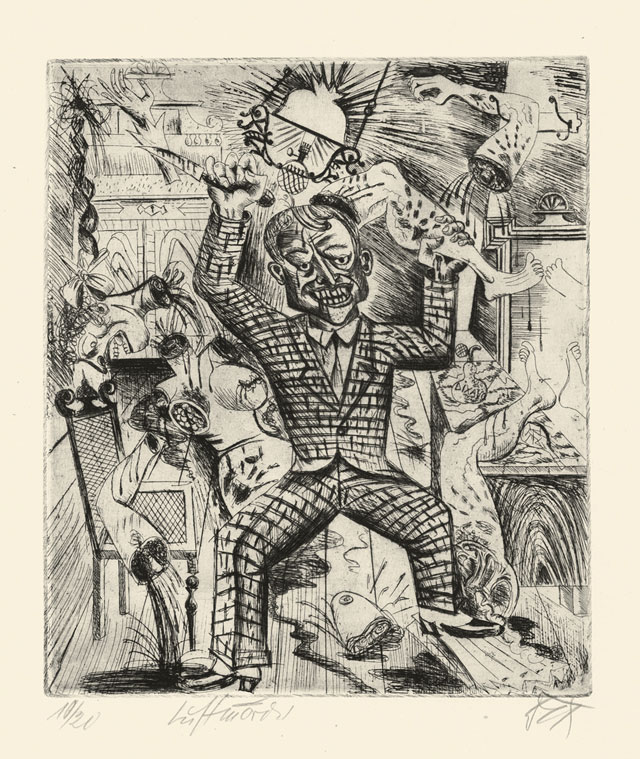

But this is not an exhibition of beautiful art. Take Otto Dix’s Lust Murder (1922), a painting that depicts the battered body of a woman, her bruised buttocks left uncovered, as a sinister man in a bowler hat leaves the scene with a demonic grin stretched across his face. And Dix’s etching Lust Murderer (1920) shows another grinning man dancing with the leg of a dismembered woman, mutilated in the most vicious ways.

[image6]

Dix was not alone in his fascination. The artist Rudolf Schlichter had, we are told, harboured sexual fantasies about hanging and high-buttoned boots, claims supported by a painting entitled The Artist With Two Hanged Women (1924). The theme of lustmord was alarmingly common in the culture of the time.

This disturbing insight into Weimar Germany (1919-33) illustrates that the unparalleled brutality of the first world war, of battered bodies and torn flesh, coloured everything that followed, including sex and desire. Dix suffered from recurring nightmares after serving at the Western Front and his etchings of corpses tangled in barbed wire, of terrifying mutilations and decay, tell a story of a trauma felt by a generation of men. But that the culture of the Weimar Republic was obsessed with sexual violence also hints – it is suggested – at some very dark reactions to the liberation of women, who were given the vote in Germany in 1918.

[image7]

In fact, women are a recurring theme. Sometimes they are distant, inscrutable or otherworldly beings. The subjects of Otto Rudolf Schatz’s Moon Women (1930) stand before us naked, save their shoes, with placid mask-like smiles and black eyes. They look like automatons, strange beings from science fiction. There is an element of threat here, too, I think. The classical column at their side is broken. Is this indicative of a life cut short, a civilisation in ruins, or is it symbolic of the threat posed to male supremacy? Such motifs usually signify the end of something.

[image3]

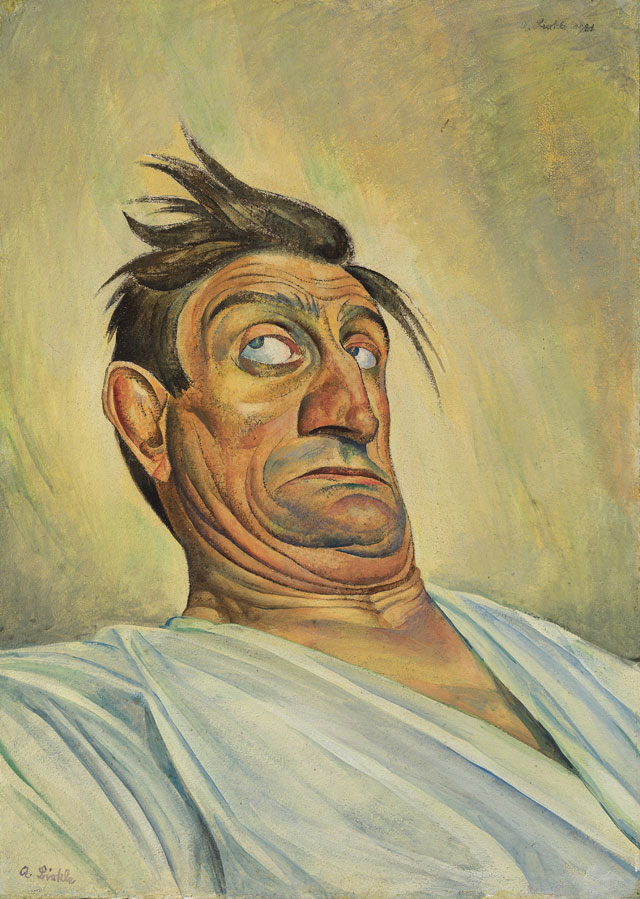

Hans Grundig’s Girl With Pink Hat (1925) has narrowed pink-rimmed eyes, which look bruised, perhaps from lack of sleep. She is a frightening prospect, again, not entirely of this world – an alien being, dressed as a woman. Schlichter’s Lady With Red Scarf (1933) looks more human than the others. The artist’s wife, Speedy Schlichter, stares at us unflinchingly – there is almost a challenge etched on to her taught face – but the backdrop places her in a landscape that might have been lifted from an HG Wells novel. These newly enfranchised beings may well have seemed an intimidating prospect to the men of the Weimar Republic.

Jeanne Mammen’s women have much more personality. They reflect the increased freedoms of the Weimar Republic’s Golden Era, a short period of increased economic stability, before the economic crisis of the 1930s. For just a few years, the population boomed and liberal values prevailed in the nightclubs, a place where women were now readily accepted as patrons, not just as cabaret acts. Mammen’s powerful women make the most of these new freedoms. They dance and drink; some flirt with men, some are stylishly androgynous and flirt with each other.

[image4]

Free Room (1930), exhibited here, depicts three prostitutes at a window. They have strong, knowing expressions and, one imagines, are full of sass. When Hitler took power, the magazines that Mammen worked for were shut down and, for a time, she was forced to sell books on the streets to make ends meet. Hers were images of women free to be women, before they were expected to become baby-making machines for the Third Reich.

In the last room, the tortured heart of Germany is laid utterly bare with the religious art of the era. Albert Birkle was only 21 when he painted Crucifixion (1921). Jesus hangs from the cross between the two thieves who were said to have flanked him. They appear starved and already in the process of decaying. Their hands form twisted claws, reminiscent of the corpses on the battlefields of the first world war. Birkle served as a soldier during the war and drew depictions of death from his experiences. And Herbert Gurschner’s Lazarus (The Workers) (1928) offers a similarly gruesome take on the story of Christ. Where the resurrection is usually painted as a miraculous event, in which Jesus emerges from the tomb looking calm and rosy, Gurschner’s saviour can be more closely compared with a scene from a zombie film. Jesus steps forward, clawing at his wrappings, gaunt and green and miserable, much to the understandable horror of an attendant group of bricklayers.

[image2]

A number of the artists exhibited here featured in Hitler’s exhibition of “degenerate art”, alongside cubist and abstract works. These were movements that went against the ideals of the Third Reich, and the romantic realism that seemed commensurate with their twisted ideals. Magic Realism represented the new, the strange, the unsettling and, in many cases laid bare the tortured heart of a society traumatised by war. That it is here now, that it isn’t pretty, is important. It is unflinching, sometimes violent, but most of all, it tells a story that must not be forgotten.

-1930.jpg)