Maggi Hambling: Walls of Water

National Gallery, London

26 November 2014 – 15 February 2015

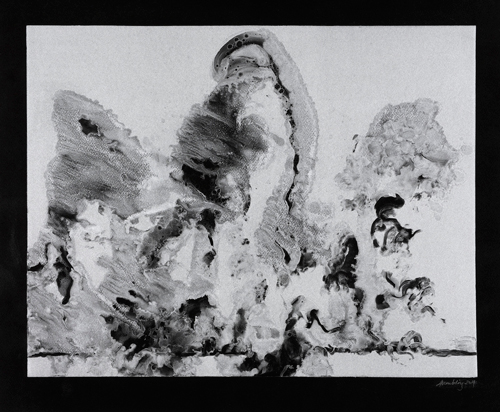

Maggi Hambling: Walls of Water: The Monotypes

Marlborough Fine Art

3 December 2014 – 10 January 2015 (extended to 17 January 2015)

by ANNA McNAY

In 1980, Maggi Hambling was the first artist-in-residence at the National Gallery. A controversial character, whose public sculptures have divided opinion and who is known for her outspoken opinions, she is also a passionate painter. Despite being almost 70, she considers herself still to be learning about the joys of oil paint and feels lucky not to be in a profession from which she is compelled to retire. With two concurrent shows, Walls of Water – the paintings and the monotypes – at the National Gallery and Marlborough Fine Art respectively, and a further exhibition and book due in March 2015, Hambling invited Studio International to her south London studio to talk about the sea, life, death and love.

Anna McNay: Your paintings of the sea began in 2002 after you witnessed and absorbed the excitement of a storm.

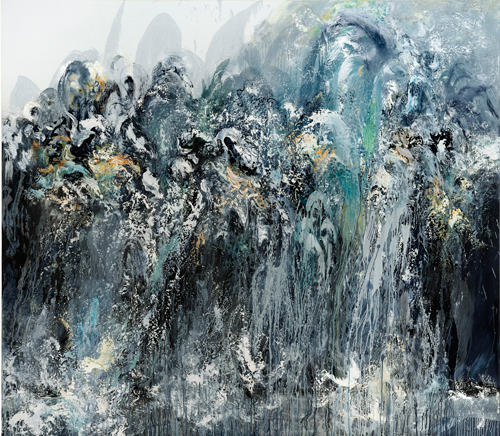

Maggi Hambling: Yes, that’s right, November 2002. I’d made the maquette for Scallop [her sculpture of a scallop shell made in memory of the composer Benjamin Britten, which sits on the beach at Aldeburgh in Suffolk] that summer and then, of course, there was a pause to begin to collect the money because it wasn’t publicly commissioned – I’d just decided to do it. So, during that pause, I’d driven to the sea early in the morning and there was this huge storm raging and it was very exciting. I went back to the studio – it was a Sunday– and I remember that it wasn’t until 3 o’clock in the afternoon, with the storm still raging in the trees and grasses all around, that I asked myself what the hell I was doing, painting from memory this little portrait, 12 inches by 10, of a London beggar, when what was inside me was the storm. And so, on that first little canvas, I changed a London beggar into a raging storm, from memory of what I’d seen that morning. And that was the first of what I’d now call the North Sea paintings. They have gone on and the ones at the National Gallery are the biggest I’ve ever done.

AMc: Are they still all done from memory? I read that when you are at home in Suffolk, you draw the sea daily, very early in the morning. Is this still the case?

MH: I do go to the sea a lot. I go quite often in the early morning before anyone else is up, apart from the odd fisherman, and draw the sea in a sketchbook. I don’t look at those drawings again necessarily. They’re just like a pianist doing his scales to get into that energy and movement. I suppose you might call them working drawings, but really it’s just a thing of getting back in touch with the subject. And there was certainly no chance of drawing these enormous high waves crashing on to the sea wall at Southwold – I hadn’t got my sketchbook on me. I just happened to be there and these huge, alarming and beautiful waves were crashing, and it was as if the sea wall that goes along the bottom of all these pictures was dissolving. So the wall of the title is a double thing: the sea wall and then this wall of water coming at you. And, I must say, one or two people have said that they have stood in the middle of room one at the National Gallery and have felt as if they were on the sea wall, which is great.

AMc: There’s certainly a large amount of power to the paintings – and ferocity. When I was looking around the gallery the other day, I was eavesdropping a little on some of the other visitors and it seemed that a few people were unaware of whom the artist was and were talking about “him”. Do you think there is something masculine about these works? Is it the powerful nature of the sea and the waves?

MH: As Picasso said: we’re all partly male and partly female and you have to bring the whole thing together to make a work of art. I remember being told at Ipswich Art School by an artist called Lawrence Self, who taught there then, that drawing is the male side – the structure and everything – and colour is the female side. Very often at art school, the girls seem to be ahead because they have a natural feeling for colour and paint, but the boys catch up on that, whereas not many of the girls catch up with the drawing. When I used to teach in art schools, this did actually seem to be rather true. But obviously this thing Picasso says is the most important: you have to bring the whole thing together. My great thing is that the subject dictates to me, so those waves are in charge of me as I try to paint them. If I were painting your portrait, you would be in charge of me. Do you see? I try to be a channel so that the truth of those waves, or the truth of the person in front of me, if I’m doing a portrait, can come through me on to the canvas, or through me into the sculpture or the monotype. The subject is in charge and that’s very important. My art teacher at school said: “A subject chooses you, you don’t choose a subject.”

Somebody told me some years ago – and I don’t know if it’s true or not, but I like it anyway – that the only thing Rembrandt actually said was: “I have painted nothing but portraits.” If you think about that, then the tiniest chicken coop in the tiniest etching is a portrait of a particular chicken coop. In other words, he doesn’t generalise. The subject is in charge of him. With regards to these waves, a lot of people will say Turner, but I much prefer Constable because I think quite a lot of the time Turner is doing all this wonderful stuff which has more to do with him than the subject, whereas, with Constable, it really is the Suffolk mud and it really is the Suffolk Punch pulling the cart. You can smell the Suffolk air, so it’s much more honest, in a way.

AMc: Do you also see your wave paintings as portraits of the sea, or of a specific wave, since they are almost composed as such, with nothing else – no real backdrop – on the canvas?

MH: Yes. My last show in London, five or six years ago, was called Portraits of People and the Sea. So each time I paint a wave, it’s a portrait of that wave, I hope.

AMc: You’ve made reference in the past to the sea being like love in its engulfing nature. You’ve also talked about it as something sexual – a metaphor for an orgasm. Can it be both of these things at once?

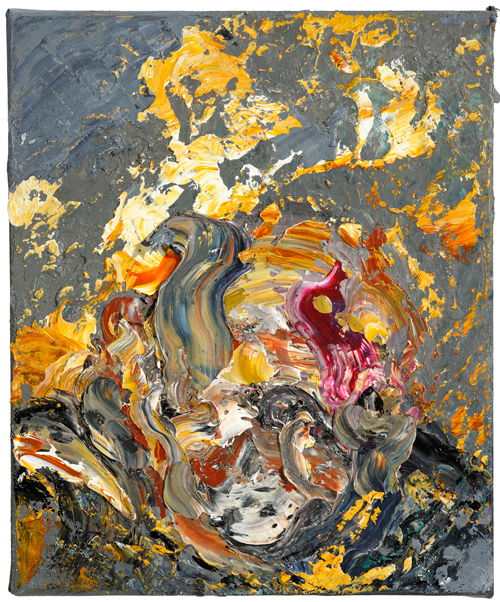

MH: Well, oil paint is very sexy stuff, right? You have to love oil paint to work with it. I keep discovering things about oil paint that I didn’t know it could do before. However long an oil painting takes to make, you have to bring the whole thing together into one moment. I try to make that moment as intense as falling in love. The incoming wave, coming in, gradually, gradually, and then crashing, is an orgasmic moment. So sex is there. And death, of course. The formal movement is the crashing down of those waves, but also they’re going up again so it’s life and death together, I hope, however pretentious that sounds. I think great art always has this ability of bringing life and death together into this unknown territory where they’re side by side, the same thing. Like how they think of death in Mexico, where they handle it a lot more healthily, unlike here, where we shove it all under the carpet and pretend it doesn’t happen. It’s best to face it.

As you probably know, I have painted quite a lot of people for a long while after they’ve died, which is ironic, I suppose, because obviously I’m trying to paint their portraits with as much life as possible. If anyone’s ever loved anyone who has died, they carry on being alive inside the person who loved them. I think that’s where artists of whatever kind are very lucky – to be able to grieve for a loved person in a very positive way. You can write an opera about it, or write a poem, or paint something. We’re very lucky. We’re also very lucky that we don't have to retire like tennis players or ballet dancers because we can go on – or I go on – hoping all the time to get a little bit better. I mean, you think of late Titian and late Rothko and Rembrandt, they’ve just gone on getting better and better.

One never knows if one improves, but I’m still learning things about oil paint. The paint goes on very fast, but there can be weeks in between before I change something and then, of course, that changes everything, so you have to change something else. The monotypes also have to be made quickly because you get to a certain stage and the ink begins to coagulate and you can’t work it. I just tear up the bad ones. It’s less trouble than taking a Stanley knife to a canvas, which I also do. A painting comes alive and dies, comes alive and dies, lots of times in the course of things. And if it finally dies, it has to go. Stanley knife. Depressing. Have a whisky. Some paintings you’ve just got to cut up. There’s enough bad art in the world.

AMc: There’s also the risk that someone might x-ray them at some point in the future.

MH: Yes, I think the x-ray machine will have quite a few surprises.

AMc: When people die, why is it that you paint them as dead?

MH: I don’t paint them as dead, do you mind? I do not paint them as dead! With the Henrietta [Moraes] series, even though she’d died, I did many paintings of her alive. And the same with George [Melly]: there were many paintings of him singing, even though he’d died.

AMc: I know, but you do also make some drawings of them as dead.

MH: As dead. Oh yes.

AMc: Is that part of the process you mentioned before, of grieving?

MH: My mother was the first person I drew lying dead in her coffin.

AMc: I suppose it makes for a good model – they’re not moving at all.

MH: Well, exactly so! When I went home for the weekend, my father would just watch the television or read, or whatever he was doing, and I’d draw him and he wouldn't take any notice. My mother, she would sit for about two minutes and then she would rearrange her hair, then she would take her specs off, then she would say: “Have you finished?” So when she was lying in the chapel of rest in Hadleigh in Suffolk, I thought: “Got you now, mother! You’re not going anywhere now.” She was the first person I drew in the coffin, and then my father, and then Henrietta. I didn’t actually see George in his coffin, so I did one from my imagination. And then I drew them alive again. My art is usually all imagination, imagination, imagination.

When my father was dying I sat beside the bed in Ipswich hospital and made a whole series of drawings. The sketchbooks are in the British Museum.

Have you ever come across someone called Sebastian Horsley? He was an artist and a writer and Sarah Lucas made a film of him being crucified. He went to the Philippines to be crucified as a work of art. You can pay and be crucified there if you want. You are actually put on a cross and they put nails through your hands and there’s a little shelf thing that you put your feet on. And for the first time ever, when Sebastian did it, the little foot thing broke, so he was literally hanging from his hands and the cross fell forward. Luckily, he was caught and saved – otherwise he’d have done the whole thing. Anyhow, he died five or six years ago and I made a series of portraits of him.

It may not all be bad, you know, when we die. It may not all be bad. We don’t want to die, on the whole, but who knows? It might be a few laughs! We don’t know.

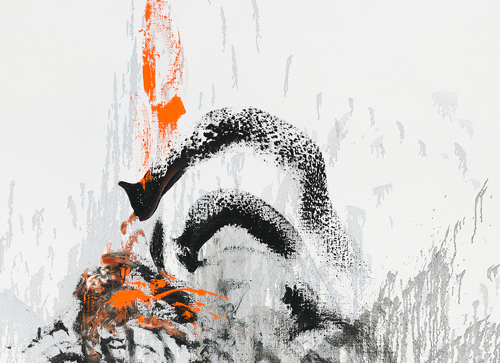

AMc: One work in the Walls of Water exhibition – also of crashing waves – has the subtitle Amy Winehouse. How did this come about?

MH: I’ve always been very moved by her voice, the nakedness of her voice – it’s an extraordinary voice. When she died, which clearly was a tragedy, I thought I must do something about it and I started a big portrait head of her, four feet by three. I worked on it for two or three months, I think, and I didn’t like it, so I started another one on the same sized canvas, of Amy’s tiny little figure singing in a great big space. That went on for another couple of months and I didn’t like it. I destroyed them both. The next day, after getting rid of all that, I painted the one that’s in the National Gallery because she was so inside me by then. But the one in the National Gallery couldn’t have happened if I’d not done these couple of pieces of rubbish. Her mother got in touch and I met her last week in the show and we stood in front of the painting and it was great because she said: “That really is her colour and you can really hear Amy in that, it’s really got her movement.” It was wonderful because she’s not a sophisticated person about painting, but she really saw her in that work.

AMc: As well as the Amy Winehouse painting, there is another painting in the National Gallery show that has a specific title: Wall of Water XIII is titled as War. What is the significance of this?

MH: Last year, 2013, for SNAP, Art at the Aldeburgh Festival [held in Snape Maltings], I was asked to make a work in response to the work of Benjamin Britten, as it was his centenary. I was working on the Walls of Water, because they started towards the end of 2010, and it was his War Requiem that I knew I wanted to try to respond to. That Wall of Water painting, War, was a response to war, and it’s going to be in the King’s College show, War Requiem and Aftermath, I am having early next year. That’s the painting I was working on before all the paintings that were in the installation at Snape. That installation has been purchased by the Monument Trust for Snape Maltings so it can be installed every year. It was on during October this year and it’s going to be on next year in April during the show at King’s College. I made a little film of the installation and that will be shown at King’s College.

I can remember hearing Britten’s War Requiem on a record quite soon after it had its premier in 1960-whatever-it-was and I was pretty stunned by it, by its strangeness and its grandeur and its pathos. It was like first hearing Oscar Wilde and that voice coming from another place. It was the same sort of feeling. So I knew that was what I wanted to respond to with Britten.

The King’s College exhibition will include a lot of other works, too. For example, Gulf Women Prepare For War. That’s usually in New Hall Cambridge, but we’re borrowing it for the exhibition. I saw this photograph in the paper in 1986, before the Gulf war, and it was just such a shocking image. These women. You didn’t, in London, see many people around dressed like that at that time.

There’s also War Coffin – a piece which now belongs to the Tate – a bronze, with heads hanging upside down, which rocks and makes strange sounds as one bit of bronze hits another. The Tate wouldn’t lend it for the show, so this morning we went to make a film of it moving, which will be in the show. We had to work with this rather frightening conservator, whom I thought wasn’t going to let me touch my own work. The Tate considers it too fragile to have on show. It’s in its storerooms. It chooses when things come out. The best way to get something on show at the Tate is to die, but I’ve no intention of doing that. It has quite a lot of my work. I remember when my portrait of Frances Rose, the old lady who used to live next door to me, was shown in a portrait show some years ago next to a Hogarth and there was a lot of fuss. People like making a fuss about things. They’ve got nothing else to do.

Then there will also be some Aftermath sculptures, which came after the War Requiem installation and all began with logs. They’re cast in bronze. I make the sculpture first in wood. You can never tell when things decide to happen. Some of the pieces of wood, I’d had for a long time. I find these bits of wood everywhere, all over the place, and if it suggests something, I encourage it to become that thing. I add bits and take bits away to help it. And then they’re cast in bronze and etched, so they come back to me this nasty khaki colour, and then I prime them with several layers of primer and then I paint them using oil paint.

The titles are only suggestions really. That’s why I’ve insisted on using small, not capital letters. Like with the paintings, really, people can see whatever they want to in them. I like the fact that people can see faces and animals and all sorts of things in those paintings in the National Gallery. I don’t put them there consciously, they just happen when I’m making a painting, and then I look at it afterwards and see various things in it.

AMc: If we can return to Walls of Water, it looks as if you work a lot with your hands. I think I could see finger and palm prints in the paintings as well as in the monotypes?

MH: Yes, sometimes I use my hands. Or great big knives, or brushes, or rags, or anything. It’s more straightforward, I suppose, with the monotypes, because the plates are inked up with dense black velvety ink and I remove the ink with solvent and my hands and rags – so it’s like drawing with light. That’s more straightforward than the paintings, which involve colour.

AMc: Where do the colours come from? Do you see them in the water, or are they more associated with the feelings and emotions that you experience?

MH: Well, people think the North Sea is grey, but it isn’t at all, it’s full of extraordinary colours: golds and bronzes and silvers and turquoises – all kinds of colours. There’s a progression around the walls of the gallery from left to right as you get to the more exotically coloured ones. The more exotic colour for some reason entered the work in March 2012. March is the sexiest month for me, when everything’s been flat and black. More people kill themselves in February than in any other month, apparently. Then, in March, you start to see all these things forcing their way up out of the ground. That was the change of colour. I could also say that the sea can become all of those colours when the sun is setting opposite it or the sun is rising. The imagination comes into it.

AMc: Perhaps the sound as well, because you’ve said that you are trying to capture the sound of the waves hitting the shingle?

MH: Yes, well, the waves hitting the sea wall. One or two people have said they can hear the waves crashing and that’s great. There were those waves crashing and I absorbed the whole thing and then started painting. I hope that on those canvases the waves – that is, the paint – are crashing as loudly and extraordinarily as they were when I saw them. Again, it’s all about being a channel. The marks are dictated by what’s in front of me, not by me. There’s an awful lot of narcissistic art about that doesn’t seem to derive from a subject outside the artist. It’s awfully tricky, you know, this painting malarkey.

AMc: Is it a very physical experience, making your works? Does the process energise you, or use up a lot of energy – or both?

MH: Oil painting can make you feel as if you’re there while it’s being made. Somebody looking at it can feel, with a late Titian or with a Rothko or a Van Gogh, as if they are there with the work being created in front of them. That’s something oil paint can do. So, yes, I suppose all these marks are energetic. They jump about. It’s all physical.

AMc: Does it tire you, the process of making the paintings?

MH: It does when it goes wrong. I’m very much an early-morning person. I get up around 5am. We all have different times of day. Some people have their best energy in the evening; some in the early morning. Somebody said it was to do with when you were born and I was born quite early in the morning.

AMc: Do you paint every day?

MH: Yes, otherwise I go pottier than ever. I’m very boring. I hardly ever go on holiday. I would get bored. My reality is making things. That’s what is real. The rest of it is just the rest of it – have a few laughs. It’s very serious business trying to make a piece of art. I’ve had these four glorious years working away in Suffolk and these paintings happened and the sculptures happened and I’ve not had any shows and now suddenly there’s the one at the National Gallery quickly followed by the one at King’s College. That’s fine. But then suddenly you have to keep talking about it and not just keep making it. I suppose people have always asked artists about their work, but nowadays you seem to have to do a lot of talking about it.

AMc: Do you read reviews of your shows?

MH: Oh, yes. Charles Saumarez Smith at the Royal Academy said to me a few years back that what he really wants is a bad review because nothing brings people in like a bad review – they all want to see if it’s really as bad as the critic says. It’s swings and roundabouts. What can I do about it? There was all that huge fuss about Scallop, which amazed me as I couldn’t see why there would be any objection. There are a lot of people around with very little to do.

Brian Sewell did a splendid double-page attack on the Oscar Wilde sculpture when it was unveiled and then, a few years later, he came to a show called Waves and Waterfalls that I had, about which he raved, particularly about the waterfalls – he actually wrote: “Hambling succeeds where Leonardo failed.” Extraordinary! We became chums, Sewell and me, because he’d always made me laugh. Many years ago, there was a letter that some people in the art world were getting together, to complain about him writing about contemporary art, and I refused to sign it because he’d always made me laugh and I’d never sign anything against anyone who had made me laugh. I think he writes extraordinarily well. His autobiography is unputdownable.

AMc: You once promised Derek Jarman that you would use the word “queer” instead of “gay”. Have you stuck to this promise?

MH: When I remember. I do find myself saying the word gay and I think: “Oh, Christ! Queer!” It was very much in the time of Margaret Thatcher and Clause 28 and all of that and Derek felt very much that this word gay was too genteel. At that time, if you were queer, you were still treated as a sort of outcast and so the word queer said what the situation was in a far stronger way than the word gay. So, when I remember, I say queer.

AMc: You’re a patron of the charity CoolTan Arts, which seeks to create opportunities to help enhance mental wellbeing through the power of creativity.

MH: Yes, it does wonderful work. I seem to give a painting away every week for cancer and they still don’t seem to be able to cure it so I might stop. I give a lot of work away. In fact I’m going to an event tonight where I’ve given some work to raise money for children in Syria. I’ll usually give things if the money helps. I give quite a lot to animal charities. I give the most each year to something called the Brooke animal hospital, started by two Victorian ladies, apparently, seeing how donkeys were treated in Africa. Each year I give them a little more money and I say: “I’ll give you a little more money if you don’t send me your newsletter.” And then comes another newsletter full of these horrible pictures. I don’t look at it for three days and then I pour myself a large whisky and open it up and think “yes, all right” and give them some more money, but say: “Don’t send me the newsletter.” Of course, they continue to send me the newsletters and each year I put it up a little bit more.

And I do care very much about the way we’re destroying the planet. I’ve started some work about that. I belong to Greenpeace and I’ve given pictures to the cause of trying to save bits of the planet. Otherwise in 100 years, there won’t be anything left. There won’t be a house sparrow, a polar bear, woods … I think I’m quite lucky to be alive when I am. People say to me: “So how can you drive a Bentley or a Chrysler or a big car like that?” I say back to them that I’ve only been abroad once in 10 years, or something like that, and you could run a fleet of Bentleys and Rolls-Royces for a whole lifetime and it wouldn’t take a millionth of what it takes for one aeroplane to get up off the ground. So, shut up!

AMc: A lot of your works – for example, the Oscar Wilde sculpture and Scallop on Aldeburgh beach – are places inviting people to sit or stand and have conversations, with themselves, with others, with nature, with the past … Is this something you consider to be a purpose of art? If, indeed, you consider art to have – or to need to have – a purpose?

MH: Well, in the case of Scallop, the idea was for a lone person walking along that bit of beach to have a place where they could sit and contemplate the horizon. A lot of people talk to the sea. I started talking to the sea when I was tiny. I’d go into the sea and talk to it. I can’t remember what I said, but anyway. As I get older, I listen to it. You look at the horizon and it’s corny and inevitable, but you think about life and death, the big things. The subtitle to Scallop is A Conversation with the Sea, and as it has worked out, it’s always covered with children, lovers have made use of its lower regions, people have got married at it, people have had funerals at it – it’s become a place of pilgrimage, which is really quite surprising. I think it’s all rather wonderful. And the sculpture with Oscar Wilde is called A Conversation with Oscar Wilde and so it was very important to me when I made it that it wasn’t up on a pedestal above the people, being a dilettante creature, because he’s very much a man of the people; his work is full of humanity. The idea of sitting and having a chat with him, having a laugh with him, and having a fag with him was very important. I like the fact that people can meet there. “Meet you at the Oscar on the way to Heaven.” Both those pieces were made to be used. I mean, you can just look at Scallop with the sea behind it and the sky above it and the shingle beneath it and see it as a work of art, or you can go and sit on it or under it, or lean on it, or whatever you want. At least it’s out in the world.

• Maggi Hambling: War Requiem & Aftermath will be showing at the Cultural Institute at King’s College, London, from 4 March to 31 May 2015.

The monograph Maggi Hambling: War Requiem & Aftermath, by James Cahill will be published by Unicorn Press on 4 March 2015, rrp £30.