Lydia Gifford: To. For. With

Laura Bartlett Gallery, London

26 March – 10 May 2015

by HARRY THORNE

At a time when so much emphasis is placed on the exhibition as an event, it is refreshing to encounter an artist who has no delusions as to the significance of such an event on their artistic progression. For regardless of her previous solo exhibitions at the David Roberts Art Foundation, London, Kunsthaus Baselland, Basel, and the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, the place that is of greatest importance to British artist Lydia Gifford (b1979) is her small, unruly studio in east London. And while she concedes that presenting in a gallery setting has come to be a necessity, she is determined to not let it disrupt the organic momentum of her work.

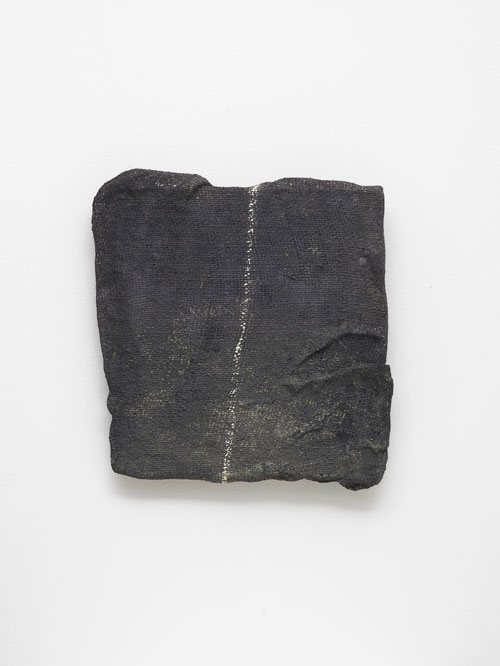

Gifford’s process is continuous – something she blames for the chaotic nature of her studio space – and this is vital to her works, raw amalgams of paint, sculpture and installation that are heavily informed by bodily movement. Fabric folds in on itself, strands of hessian hang from canvases and self-directed objects rise from floors. While held in a single, frozen state, these works appear desperate to imitate the very physical gestures that saw them created.

This reified energy is not, however, solely the result of the artist’s ceaseless productivity, but also a consequence of her character. Before we began this interview, Gifford admitted a tendency to stray from the point, and as her sentences trailed away to nothing and our conversation darted between John Cage, Yvonne Rainer, and Bethnal Green’s building works, this became very apparent. It is this inability to focus on a single subject or to favour concision in the face of digression that makes Gifford’s work so kinetic, and as a result so exciting. It cannot be controlled, and it cannot be predicted. As she herself states: “It has to be surprising and fresh.”

Harry Thorne: Talk me through this exhibition.

Lydia Gifford: It doesn’t really ever start and stop. I don’t see an exhibition as: “OK, it’s time for this; this is what I work for now.” It’s more continual than that. It did become more about my physicality and my movement in the studio though. Whereas before I was focusing on making actual objects, now I see those objects as byproducts of my own activity. It’s not about trying to make works; it’s about trying to catch something to do with movement.

I’m really interested in dance. I’m not a performer or a dancer, but I’m really interested in mime and the body and movement as vehicles of expression, and whether that expression can be put into art. Whether it can actually be present in objects, instead of those objects being static things.

HT: If you work in this continuous fashion, how do you make the decision as to which section to remove and define as an “exhibition”?

LG: For me the objects are interrelated because of the duration, the passage of time. They’re made in and around each other and they hold an energy together, so the selection process is just about working out which few objects or containers can create something interesting. I do think of them as containers of this activity or energy-containers that are trying to catch something to do with movement. I try to make each work carry a particularly interesting tension, and maybe then they work together.

It’s very much like editing a piece of film. You can make a hundred different experiences out of footage, but for me it’s quite strange. Going from that footage or community or ecosystem to a small selection is quite a strange process, and it’s one that I find a bit difficult to pass through. But I do really believe in that idea of editing down quite ruthlessly in order to create an experience or an installation, even if it may be hard for me to leave them, in my head.

HT: Does it feel almost like an accurate representation of the working period?

LG: It doesn’t feel accurate, it feels like a version, but that’s exciting to me. I think I’d like to change it constantly. I’d like to have phases where I change the choreography of it and bring out different characters. It would be interesting, reintroducing an object or switching out another altogether.

HT: Where does the title of the exhibition, To. For. With, derive from?

LG: That came from a way of thinking about the things themselves as more transitions than entities, more movements between and among each other than static bodies, things that are passing and not defined. I’m always wary of titles having such a claim over everything, or creating a wash over everything.

HT: But you still title the works themselves?

LG: The titles come from lists of words that I write and collect while making a body of work. As a material reveals a character, or reveals something about what it’s beginning to communicate or beginning to form into, I keep a list of ideas about that, and then when I have started to get to know them again in the exhibition space, I look back and just pull out a word. For me, it’s not exacting, it’s not naming, because I’m comfortable with language sitting around them. The words just hang there with them; they don’t attach themselves entirely. An ideal thing would be to call them a series of words, but then that’s getting into beat poetry territory. I’m not a linguist at all, but it’s a new thing for me.

HT: Is the transition from the private setting of the studio where the work has developed to the very public, titled environment of the gallery a strange transition for you?

LG: It’s not an easy process. For a long time I try not to think about it, but then there comes this very weird gate where that crossover happens. I’m learning about that all the time, how to let go. At times, it feels like something’s being wrenched from you, and at other times you feel quite clear about it, but it’s definitely a strange threshold, one that reveals things.

HT: Do you keep working on pieces after they have been transported?

LG: I’m trying to less and less, because I think the studio and the gallery require such different mindsets. I believe that everything always has to be adapted, but my new approach is to let things from the studio side be raw, to not be reworked, because there’s a risk of trying to tidy them up or making them seem justifiable in that gallery setting. I think that fresh actions in the exhibition space are really interesting, but this kind of tidying or preparing them isn’t the same.

HT: The works in this show particularly feel almost disjointed from the environment, somewhat turbulent in what is obviously an incredibly clinical space.

LG: I do think it’s an important thing to have that clinical element, because, in a way, it allows you to see a lot more in the works. In the environment where I make them they become part of this continually generating material mass, but then I extract them from that and I see them completely differently. It’s necessary for me, seeing then in this crisper state. I don’t think I would ever try and create the studio atmosphere in the gallery.

HT: To focus on your process a little more, can you talk about the materials you use? In your 2013 exhibition at Kunsthalle Baselland, for example, you worked with a range of found materials?

LG: I used to use a lot more recycled stuff, but it tends to change a little too much. The wood actually moves and shifts, and stains and colours come out of it. I’m really interested in this slow release of material actually. In the works here, for example, I embed quite a lot of coloured, soaked material in them, so there is a kind of slow change. A lot of my practice in the studio, a lot of my “job”, or whatever you want to call it, is monitoring things drying; it’s not “the act”.

It’s one of the things I love about what I do, waiting for layers to dry and managing my impulses, because sometimes you want to work into wet paint because you get frustrated with what you’ve laid down, but you have to have the restraint to leave it to dry. So there’s a definite kind of nurturing to be done when working with the natural way that material does things. Wood is really unpredictable, it bends and bows, so pulling damp wood out of the street, out of bins, you get lots of surprising things happening. That is really exciting on one level, but it’s also completely uncontrollable territory. I’m not entirely sure whether I want to control those things all the time, but sometimes I do.

HT: What about the incorporation of colour in the show? Like your contributions to the David Roberts Art Foundation in 2012, the works here are predominantly white, but you have also used vibrant reds and yellows.

LG: I love colour, I love playing with it, but it’s scary as well because it means so much. It’s always quite angry, but it really does talk to me. When trying to work with movement as I have been, trying to strip everything back to physical movement, I find that the muted natural tones allow that to be visible. Colour can overtake that. Occasionally it can also aid it, but again I’m still learning about that, about how to mix physical movement and colour and not make it all about colour. I think you see a very different physical register when things are muted and it’s about pulls and pinches and stretches. You are able to see those physical nuances, but somehow colour interrupts that.

It’s really interesting, that place where physical space doesn’t suffice any more, but painterly space is still attainable. They’re very different things and they have very different logics and ways of communicating, so I slip between them. I don’t think they’re entirely mergeable, and that’s interesting to me. There are contradictions all the time.

The small painting in the corner (Ember, 2015) was quite exiting. I start a lot of my practices by setting up different scales of, well you might just say canvases, but I see them more as surfaces to receive different kinds of gestures. The smaller ones are very handheld, but then the slightly larger ones, the more two-handed works, they ask for a different kind of handling. The medium ones are much more whole torso, a different kind of brush movement or limb movement, and the large ones are my whole body. I do it all on my own, I lift them all around, so for me these larger works definitely demand a very different kind of physical engagement. They really exist as a duration of physical movement, that’s exactly what they are. That, I find, is interesting, the way that painterly space is much easier to bring forward in the handheld, smaller works.

HT: Do you see them as personal works?

LG: I see them as really personal, but I also know that at a point I have to stand back from them. I’m constantly weighing up how much I should be in the work, how much I should reveal. As I was saying about the studio, there’s a threshold that’s quite strange, and it needs to be navigated.

HT: Do you see them connoting different emotional states?

LG: I think they become what they physically are. An aggressive, frustrated movement that you’re putting in the paint when you’re cutting it doesn’t necessarily create a work that has an aggressive or frustrated voice or energy. There are works that I know I’ve made very easily, in a very fluid, quite peaceful passage of my studio time, but they might have a very different energy to that when you look at them as objects. Then the other ones that I’ve fought with for whatever reason, the materials that I have pulled against and used to try and exercise a particular style of movement of the body, they end up being really peaceful objects. The result isn’t necessarily what you feel, and that’s fascinating.

HT: Do you think that seeing this particular exhibition in a completed state has changed the way you are working in the studio?

LG: This whole passage has changed how it’s working, but I don’t think seeing it here has changed how I’m working. I feel much more confirmed in the fact that my practice in my studio has to be about that passage of time, about my daily activity, and not about planning or envisioning anything. It has to be a surprise, I think. It has to be surprising and fresh, for me especially. What’s planned is just keeping in the rhythm of it really, and not letting it change the vision of the studio practice. Keep it flowing.