Thomas Dane Gallery, London

2 October – 16 November 2019

by ANGERIA RIGAMONTI di CUTÒ

“There are four simple words for the matter … colour photography is vulgar,” said the godfather of American vernacular photography, Walker Evans (he later changed his mind: “Paradox is a habit of mine. Now I am going to devote myself with great care to my work in colour”). The European forerunner of colour photography, Luigi Ghirri (1943-92), an admirer of Evans, was dismissive of snobbery about colour, using it “because the real world is in colour, and because colour film has been invented”. Schooled as a surveyor, Ghirri began taking photographs in his spare time, training his eye on his surroundings, a trainspotterish flâneur of the plains of Italy’s industrious Emilia Romagna region. Day jobs are often considered a biding-one’s-time purgatory in conflict with the creative venture, but this one served Ghirri well, informing his frontal, matter-of-fact stance that he felt reduced manipulation of the subject.

[image2]

Central to Ghirri’s photographic universe was the disconsolate, ecologically wounded Po Valley, Italy’s agricultural and industrial heartland. In one of his limpid, hypnotically novelistic essays,1 Ghirri described the morbid enchantment his heimat held for him: “I began to see the plain as an enormous sheet of blotting paper, which after swallowing all decipherable geography, also swallowed up our dreams, thoughts and deeds, which sank and then returned to the surface in distorted and unrecognisable forms.”

His fascination with the flatlands and melancholic towns of the Po valley had been affected by Cesare Zavattini, a cinematic writer who collaborated with many titans of Italian neorealism, including Fellini, Antonioni, Visconti, De Sica and Rossellini. Zavattini maintained that melancholia originated at the Po River and that anywhere else it was just a cheap imitation. More broadly, he devised the notion of “qualsiasità” (any-ness), insisting that any object or place, however humdrum or provincial, could be interesting. To this end, he invited the American photographic pioneer Paul Strand to take pictures of Zavattini’s hometown Luzzara, situated on a vast flood plain. Ghirri, in a text prefaced with Walter Benjamin’s notion that “boredom is the threshold to great deeds”, described the atmosphere of Strand’s portrait of a Po village as a “poetics of marginality”, captivating in its geography (that vacillated between the serenity of the landscape and the constant threat of natural disaster) and in the simplicity of everyday objects, such as solitary pitchers straight out of a Giorgio Morandi painting (Ghirri would also photograph Morandi’s studios, giving a poignant afterlife to the painter’s prosaic vanitas).

[image3]

The singling out of the apparently ordinary stuff-of-life was far removed from the prevailing photographic portrayal of Italy, with its cloying pantheon of tourist sites purged of all signs of the nation’s economic miracle (and its discontents). These edited-out realities – the periferia, motorways, petrol stations and consumer paraphernalia – had been tragicomically portrayed in Italian cinema, but, in photography, Ghirri felt he was working without precedent. Free of any complexes about capturing the provincial or the kitsch, he embraced their visual, theoretical and witty scope. Objects commonly viewed as kitsch could harbour “important contradictions: the mismatch between the copy and the real thing, or between the past and the desire for its image in the present … So, might we not also classify all photography as inevitably kitsch?” A taste for the tawdry and the play between reality and artifice insinuate themselves through many of Ghirri’s pictures, his images of Rimini’s charmingly tacky theme park, L’Italia in Miniatura, being a case in point. Featuring scale replicas of natural and architectural landmarks, its hyperreality must have also appealed to Ghirri’s impatience with the “Grand Tour” picture-postcard view of a congealed, nation-as-museum Italy (though he loved actual postcards). At the same time, in his tricksy visual playground, a photograph of the real Colosseum has the air of an ersatz backdrop at the end of a commonplace back garden.

[image4]

With his all-encompassing perspective, Ghirri was fascinated by the photograph of Earth taken from Apollo in 1969 as it contained every picture ever made and he often incorporated maps into his images (incidentally at around the same time that his more obviously conceptual counterpart Alighiero Boetti began his cartographic series). In his vision of the world as a container and generator of endless images (sounds familiar), some of Ghirri’s schemes seem strangely prescient, vide his photographs of the sky taken every day in 1974, or his Identikit series, “shelfies” avant la lettre in which books and records function as a self-portrait, his identity represented by what he had read and heard, but also by what he would go on to read and listen to.

He could slide, sometimes seamlessly, other times joltingly, between the utilitarian and the uncanny, the odd and the ordinary, small details occasionally darting out as if by accident, a memory of Barthes’ concept of the punctum. Ghirri also favoured visual conundrums, images in which it’s difficult to establish with certainty what one’s seeing, and occasionally, sparingly, making pictures of startling beauty – Versailles being particularly memorable, and the painterly depiction of Aldo Rossi’s ossuary in Modena’s cemetery, so distant from the emphatic portentousness of most architectural photography.

[image5]

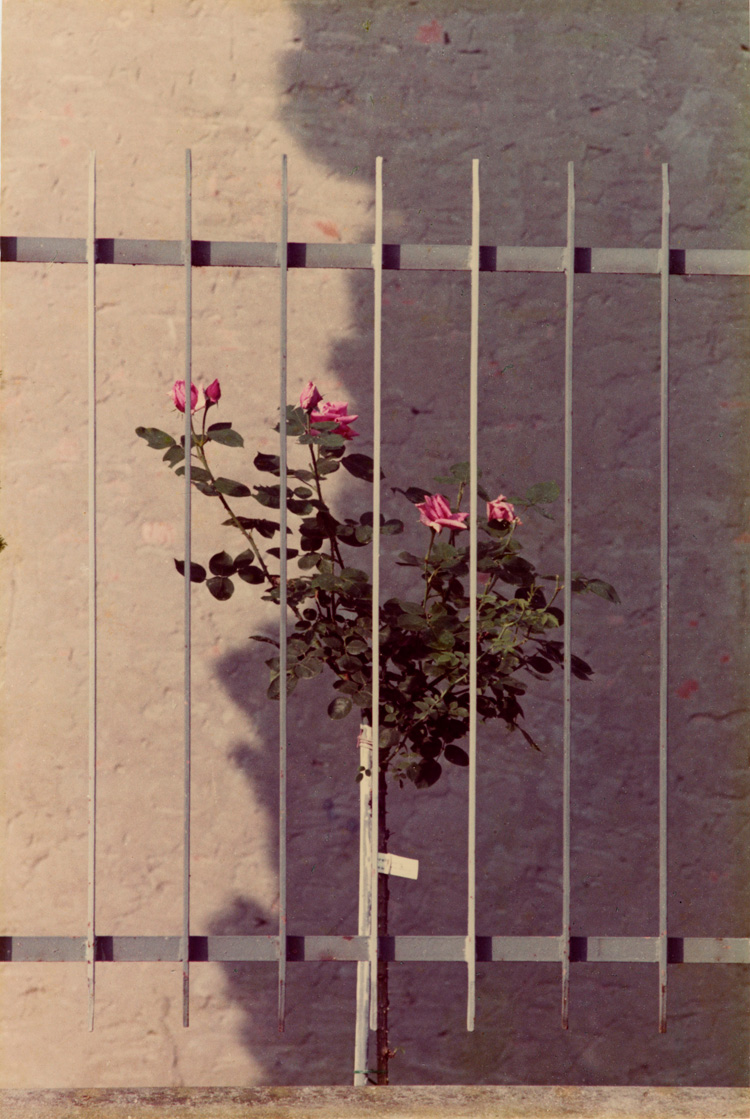

Currently on view at Thomas Dane Gallery, the series Colazione sull’Erba (1972-1974) features around 20 discreetly sized vintage c-prints and a Cibachrome, one of the works a composite of 15 prints with a sequence of a sad cypresses (Ghirri was partial to seriality, sometimes picturing successions of doors, shutters or windows in surveyor-like fashion). A study of small-town patios, porches and windows bereft of human presence, the title is a jokey nod to Manet’s succès de scandale (with his fondness for garish copies, in another series Ghirri would also portray casual diners in a restaurant with a mural of a doctored Déjeuner sur l’Herbe). Colazione showcases some of his formal mannerisms; the tenuous, slightly overexposed colour, milky light and soft Kodachrome intimacy – it isn’t surprising to learn that his images exert a strong hold on Luca Guadagnino. There’s also a studied insouciance; at first glance, Ghirri’s photographs have the look of 70s snapshots while yet feeling punctiliously calculated.

The curtain-twitching feel of these staid Modena residences, with their tautly composed plants, crazy paving and airless melancholia could seem critical, but Ghirri denied any judgmental intent in his photography: “I do not wish to operate in an unforgiving mode … but am always attempting to understand what I photograph.” Such understanding seemed to entail grasping the imperceptible tipping point between the mundane and the unnerving. Meandering around some nearby farm buildings with a friend, Ghirri’s companion remarked that he would not live there even for a day, that these spaces scared him more than any far-flung, unfamiliar spot encountered on his travels, a fear Ghirri attributed to the “deadly combination” of habit and boredom with no escape route contained with these settings.

Convinced that one had to interpret the daily world “with an open mind”, Ghirri sought – imaginatively and surprisingly – to capture precisely this ambiguity of the familiar, of everyday images hiding in plain sight.

Reference

1. Luigi Ghirri: The Complete Essays 1973-1991 is published by Mack Books, 2016.