National Gallery, London

1 October 2022 – 22 January 2023

by BETH WILLIAMSON

This is the centenary year of the birth of the English painter Lucian Freud (1922-2011) and there are currently three exhibitions in London alone. Aside from the National Gallery’s Lucian Freud: New Perspectives, visitors can also see Lucian Freud: The Painter and His Family at the Freud Museum (until 29 January 2023) and Lucian Freud: Plant Portraits at the Garden Museum (until 5 March 2023). There are a number of recently published books on Freud too. There are the exhibition catalogues, of course, but also Martin Gayford’s Lucian Freud as well as David Dawson and Martin Gayford’s Love Lucian: The Letters of Lucian Freud 1939-1954 and William Feaver’s The Lives of Lucian Freud: Youth. Anyone even vaguely acquainted with Freud and his work knows of the persona he acquired. Through his relationships with his many lovers and sitters, there is a mythology surrounding him as an individual and as an artist. Often viewed through those myriad relationships, his paintings have become understood to reflect the character of the artist as much as anything they might have to say about his sitters. This exhibition attempts to detach the artist from the mythology and understand his paintings in an art historical context, sloughing off the familial, the friendships and the lovers in favour of close looking that intends to position him more precisely alongside other artists.

[image8]

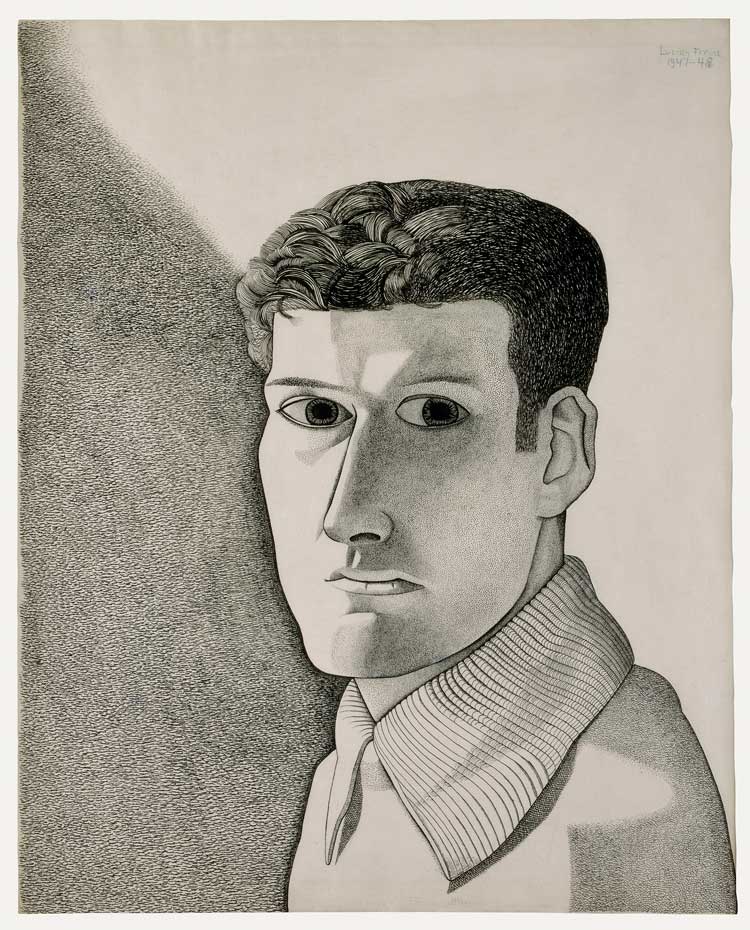

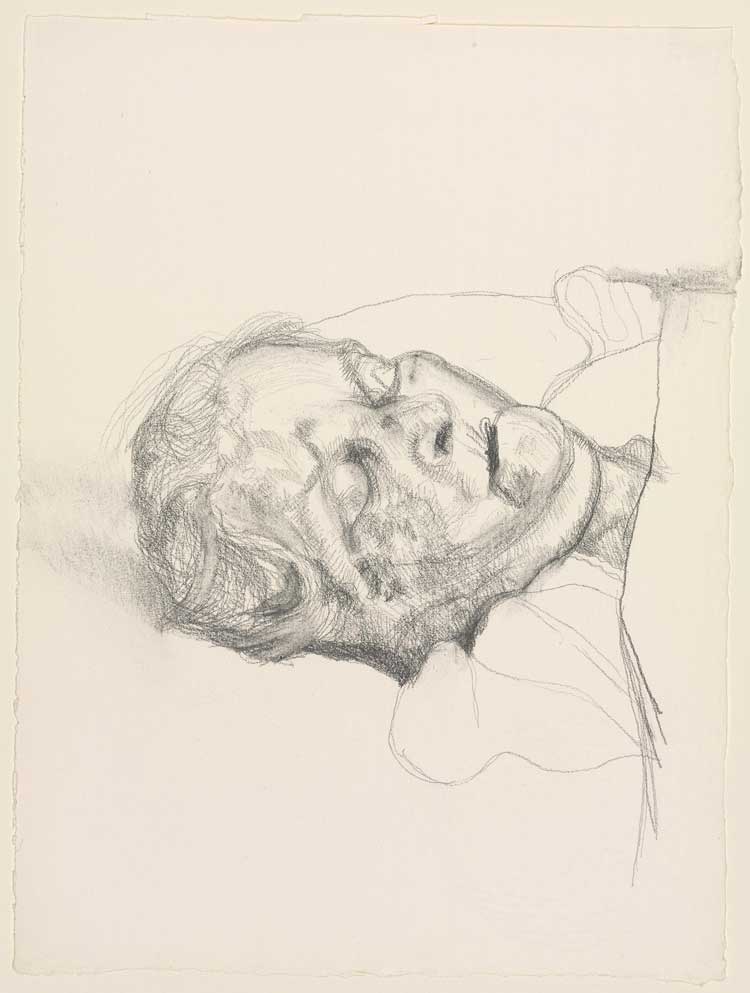

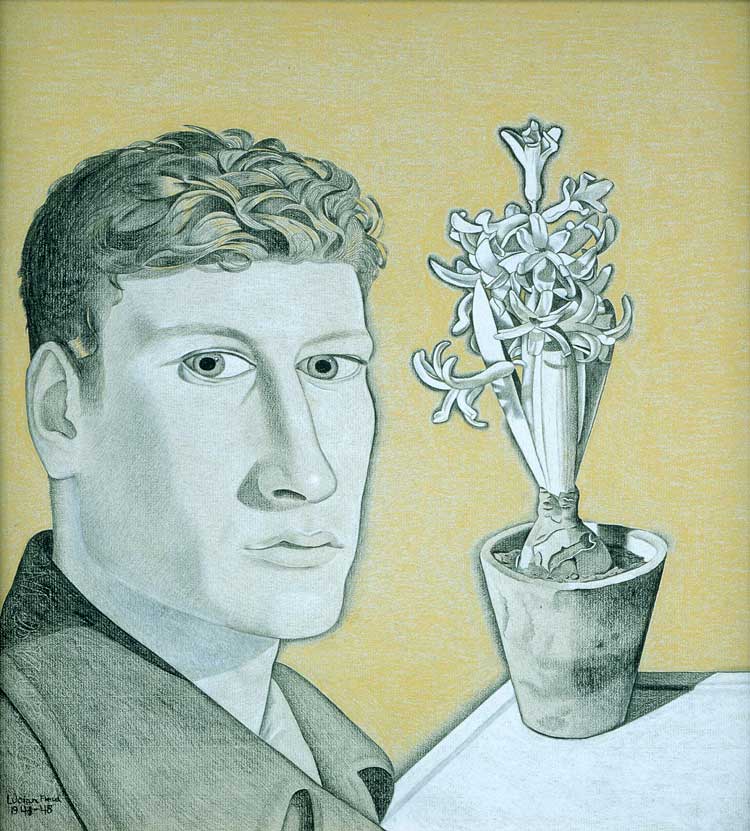

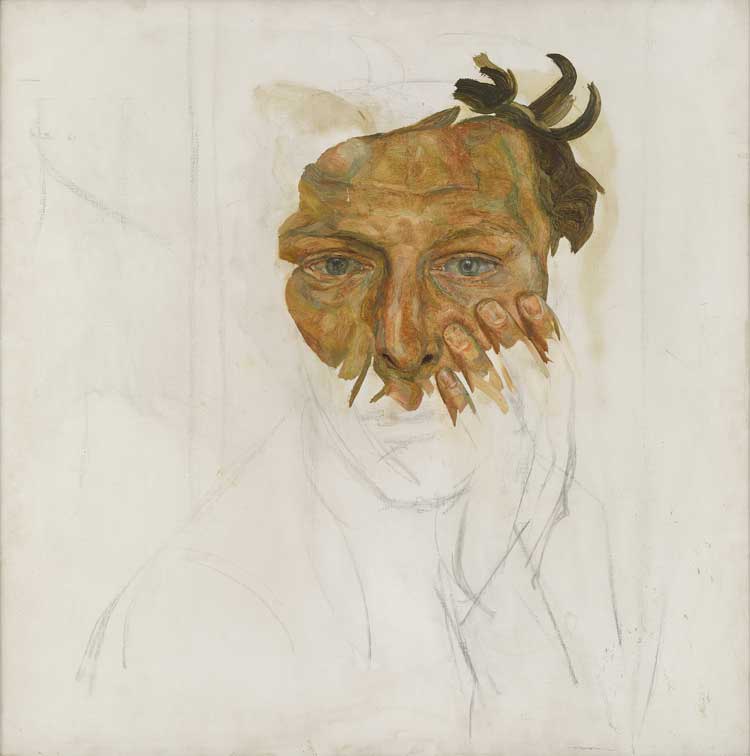

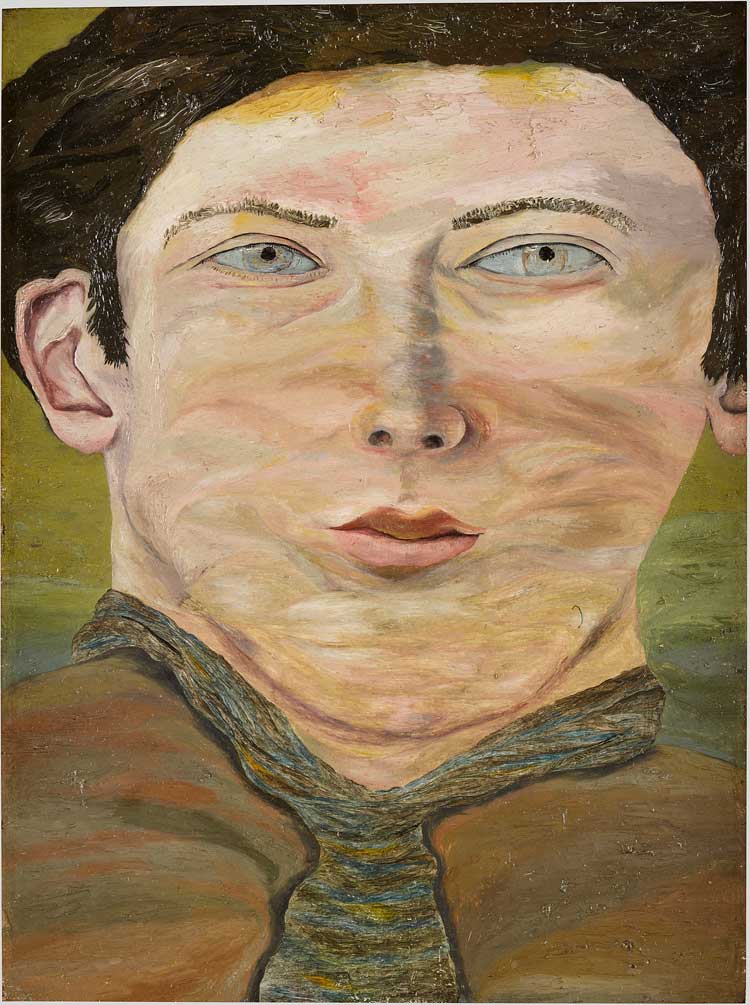

Of course, it is never possible to entirely ignore the context of an artist’s life, nor perhaps should we. This is immediately clear in Freud’s self-portraits. The very first painting of this exhibition is a self-portrait from 1940, full of uncertainty and hesitancy. Eight years later, in 1948, another self-portrait is self-assured in style and gaze while in Self-portrait (Fragment) (1956) Freud’s fingers and hair lick around his face like flames, a self-professed Lucifer, perhaps.

[image6]

[image7]

Yet, while we might think of these differing representations in relation to Freud’s maturation and changing circumstances and experiences, this exhibition takes the latter portrait, sets it alongside another unfinished portrait of his friend Francis Bacon, and points to the Renaissance technique of non-finito that Freud deploys here. By deliberately leaving these works unfinished, Freud exposes the method used to create them, showing a confidence in his development as a painter.

[image3]

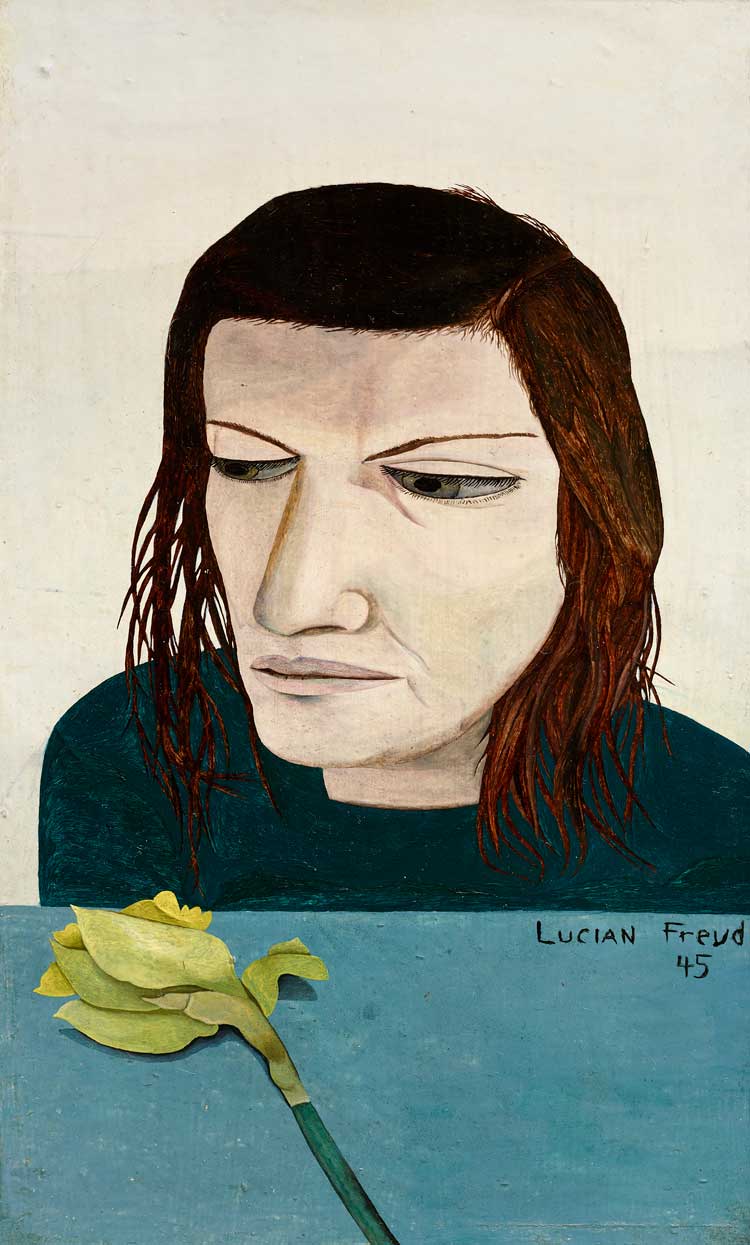

Elsewhere in the exhibition, comparisons are drawn between Freud’s painting and other periods and geographies in the histories of art. It is suggested, for instance, that Woman with a Daffodil (1945) and Girl with Roses (1947-8) both articulate Freud’s familiarity with the depiction of flowers in old master painting compositions.

[image5]

More convincing, perhaps, is the exhibition’s argument that the detailed realism of Freud’s paintings of fellow artist John Minton, a dead cockerel’s head and a dead heron (all in the 1940s and early 1950s) might be viewed in relation to northern European Renaissance painting and early 20th-century German “new objectivity”, even if Freud distanced himself from such ideas.

[image2]

The uncomfortably masculine gallery on the theme of power is full of depictions of powerful men in the arts, business, politics and elsewhere. There is his tiny portrait of Queen Elizabeth II, too, but that is overshadowed by the presence of the large and commanding portraits of men such as the industrialist and art collector Baron Thyssen-Bornemisza and the British financier and former chairman of the National Gallery Lord Rothschild, both depicted in works with the same title, Man in a Chair (1985 and 1989 respectively). Again, the exhibition points out the connections to Renaissance iconography. The power-hungry focus on heads and hands is forcefully present. The composition of the hands, we are told, recalls the German artist Otto Dix, another analogy that Freud would have refuted. With all these analogies being made, the question is whether it may have been useful to include some of these paintings by other artists in the exhibition in order that it might show the resonances rather than tell the viewer what they are looking at. That would, of course, have been a different exhibition, but perhaps an even more interesting one.

[image4]

Close to Freud’s bombastic portraits of powerful people is a cleverly positioned and dimly lit room housing just three small portraits. It is a poignant space. These affective portraits of his elderly mother, Lucie Freud, in old age are a stark contrast to his portraits of power. In charcoal and watercolour, these portraits of frailty and, eventually, death are about as personal as you can get.

[image9]

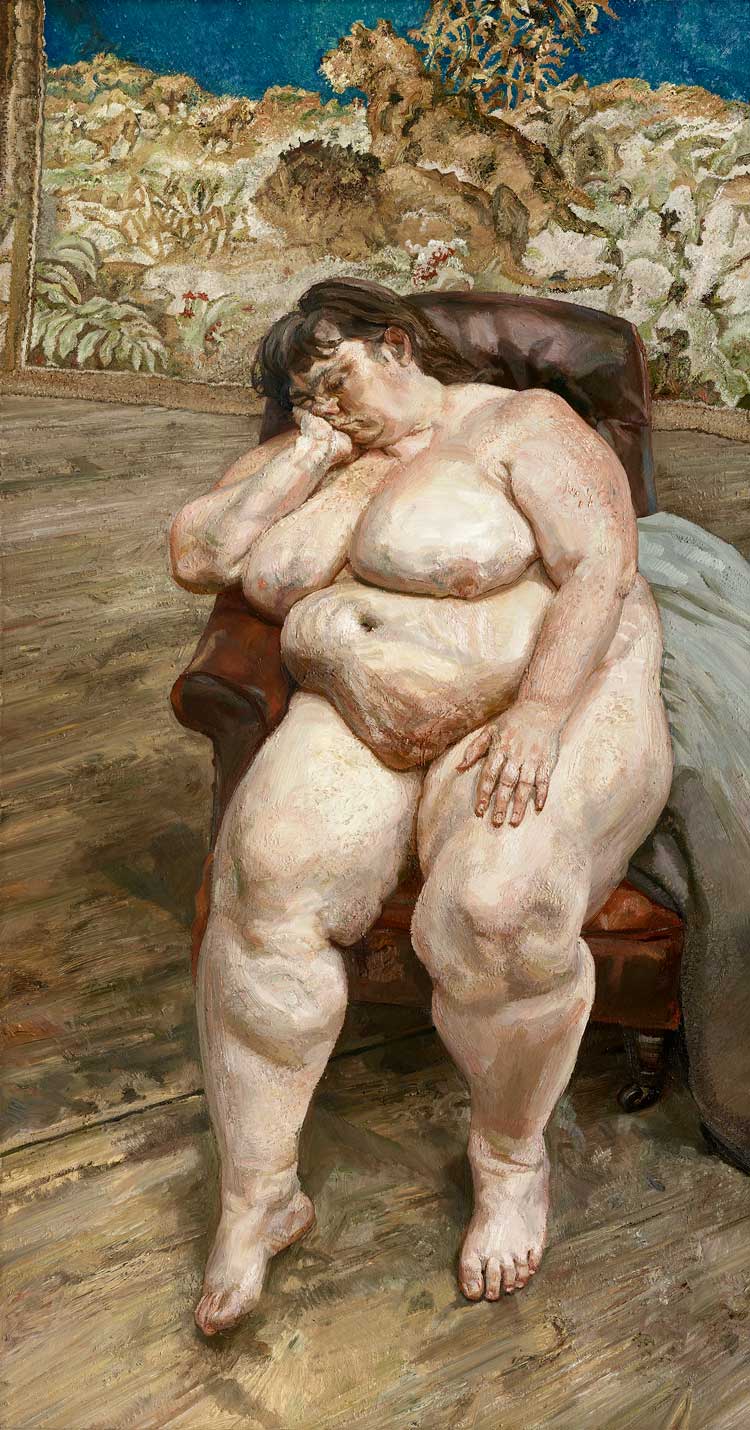

One of the fascinating things about this exhibition is how, stripped of any excess of personal context, the paintings come more clearly into focus. The shift in Freud’s techniques across the decades becomes increasingly evident and this is as obvious in his self-portraits as any other. Sitters asleep, as in And the Bridegroom (1993) or Sleeping by the Lion Carpet (1996), do not simply depict that sleeping moment but indicate the painstaking hours of sitting and painting, a repeated return to the studio and the relationship between artist and sitter. In one sense then, these monumental fleshy portraits bring us back to the relationship between Freud and his sitters, suggesting that the personal context this exhibition works so hard to rid itself of, is an unattainable goal. Nonetheless, this is a thought-provoking exhibition that refocuses attention away from the personal and back to professional and Freud’s achievements as a painter. It may be, as I am suggesting here, that these two aspects of the painter’s life are inextricably entwined, but it is nonetheless useful to at least try to prise them apart and offer a different perspective, and that is what this exhibition does.