by LUCIJA ŠUTEJ

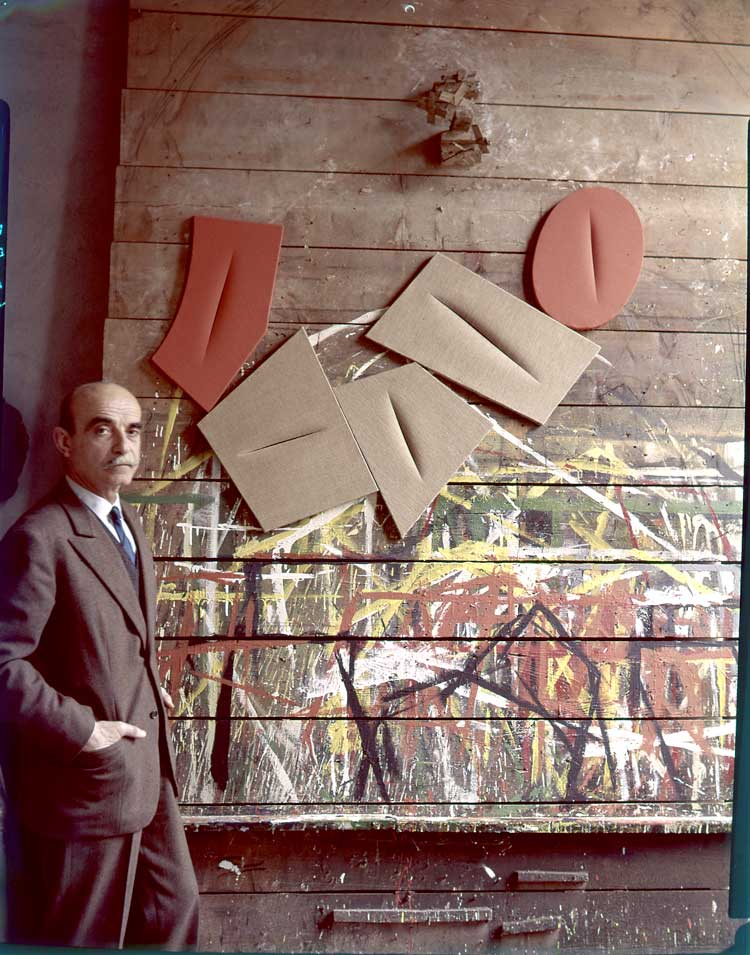

Luca Massimo Barbero is director of the Institute of Art History the Giorgio Cini Foundation in Venice, scientific adviser to the Fondazione Lucio Fontana and associate curator of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection. Here, he talks to Studio International about the late Argentine-Italian artist Lucio Fontana and the trilogy of exhibitions dedicated to him, which Barbero has curated in collaboration with Fondazione Lucio Fontana for Hauser & Wirth. The first of these, Lucio Fontana: Walking the Space: Spatial Environments 1948-1968, took place at Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles in 2020. The second in the trilogy, Lucio Fontana: Sculpture, is currently at Hauser & Wirth New York and focuses on the artist’s prolific breakthroughs and experiments in sculpture.

Lucija Šutej: With Hauser and Wirth’s New York gallery, you recently unveiled the second show in a planned trilogy on Lucio Fontana. How was the series of exhibitions initiated by the Fondazione Lucio Fontana and the gallery? Was the trilogy decided from the start? Could you tell us more about the dialogue between the shows from a curatorial perspective?

Luca Massimo Barbero: The trilogy was born from a meeting between the Lucio Fontana Foundation – which since 1982 has protected, enhanced, promoted and disseminated Fontana’s work – and Hauser & Wirth, with the intention of creating three exhibitions, namely the trilogy, that are crucial in stimulating a new investigation of Fontana’s complex oeuvre on a global level. Thus, the typification of the three exhibitions was immediately born, also in relation with the geographies and gallery spaces: for me, the knowledge of the space and the architectural mode before a show is fundamental to create an exhibition itinerary.

[image11]

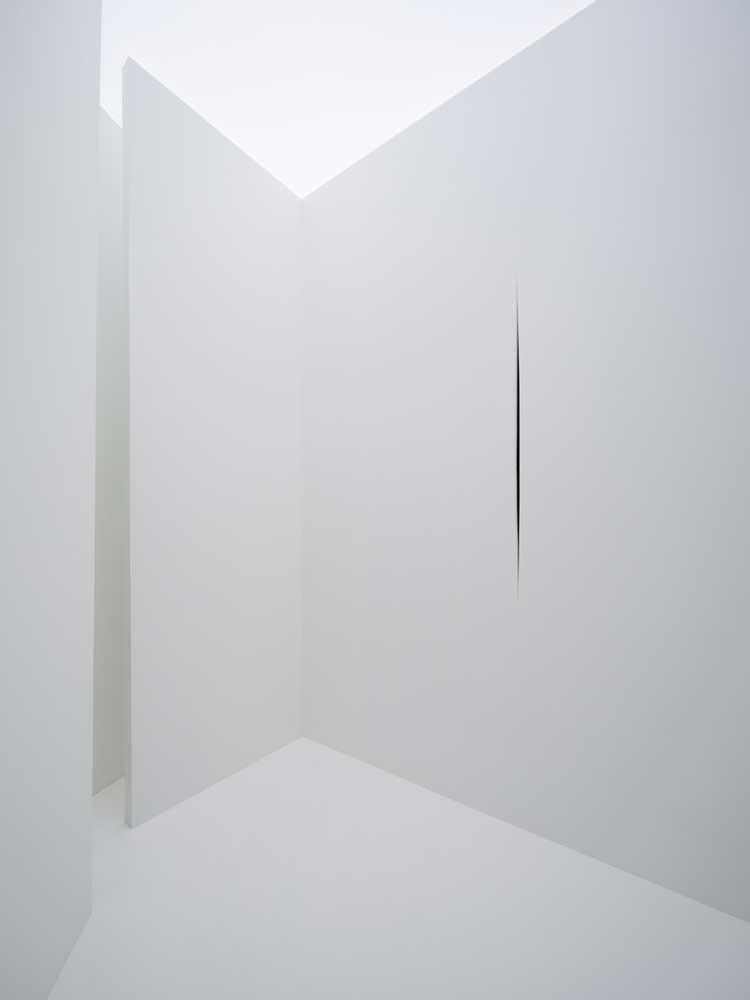

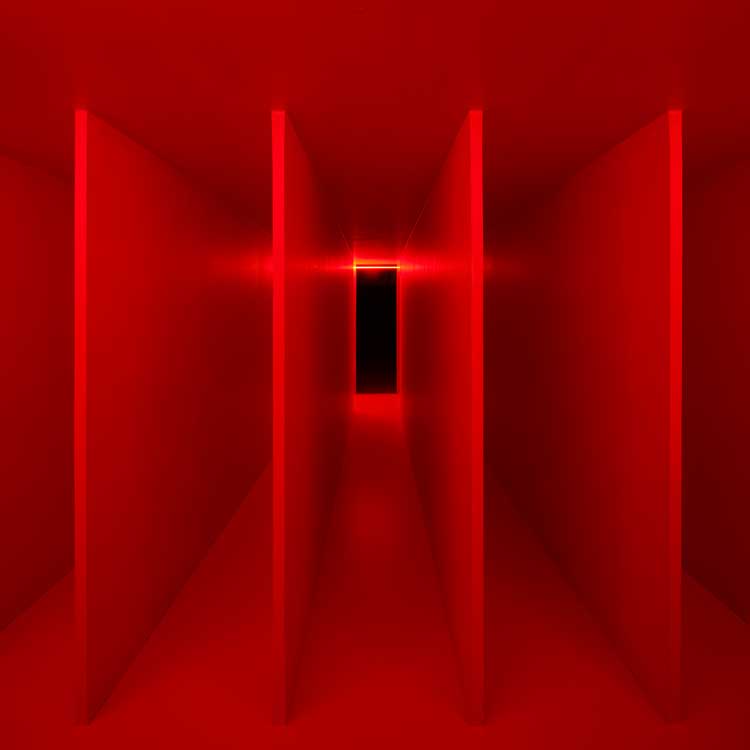

The Los Angeles space was in perfect dialogue with Fontana’s Ambienti Spaziali (Spatial Environments), with nine of his environments featured, including Ambiente Spaziale a Luce Nera (Spatial Environment in Black Light) of 1949 and the extraordinary white Ambiente Spaziale (Spatial Environment) for Kassel in 1968. Above all, though, it was an opportunity to confront the theme of light-space, and the human perceptual experience, which I think has influenced contemporary artists such as James Turrell and Dan Flavin.

[image3]

The exhibition in New York represents another side of Fontana in addition to a creator of a further space to walk through (hence the title Walking the Space in Los Angeles) in which the visitor is part of the work: here, we thought of Fontana as a sculptor from his origins in a perspective of plastic invention. As fate would have it, the gallery is located in the same building as his first solo US exhibition in 1961, at the Martha Jackson and David Anderson galleries, an experimental place, a laboratory in which to present Fontana’s coherence and visionary nature acting plastically on matter. The question posed by the critic Enrico Crispolti, and quoted in the catalogue, “What if he had been only a sculptor?” is timely: a new way, therefore, of revealing Fontana. These sculptures of the 1930s dialogue with American abstract art and the future informel in a fertile confrontation.

LŠ: The first of Fontana’s exhibitions in the Hauser & Wirth series, one of the first comprehensive exhibitions on the artist in the US, Walking the Space, focused on his contributions to conceptual art. Perhaps we could address his role in the formation of the spatialist movement? And his work with the gallerist Carlo Cardazzo, as well as his influence on the then Italian art scene?

LMB: Fontana was interested in the movement and dynamism of sculpture, as seen in the magmatic and telluric sculptures of the 1930s, which testify to the central theme, which is that sculpture is not a closed form because, through reflection and metallic colour on ceramics and in the works, he always tried to engage light and through that space.

[image4]

On Fontana’s return to Italy after the revolutionary Manifiesto Blanco, written under his direction in 1946, he spoke of a new spatial art that maintained the dynamism of intervention in matter by opening to architecture: in the Italian and international art milieu, he was already an original pioneer and not in line with the orthodoxy of the time. The first to seize the opportunity to launch him as a contemporary novelty was Cardazzo, in the gallery Il Naviglio opened in Milan in 1946. Cardazzo was a discoverer of talent and a versatile entrepreneur with galleries in Venice and Rome, as well as in Milan, and a publishing house. He cultivated important international relationships, published catalogues and organised cultural events in which he also involved film stars: in short, he was the prototype of the great gallery owner of the 2000s. He made Fontana an example, but above all, one of the new personalities of the contemporary art world. Cardazzo immediately considered him the great terracotta master of the 1930s, and gave him the opportunity to create the Ambienti Spaziali (Spatial Environments) and the new Buchi (Holes) works that, as early as 1949, introduced a revolution in the way and concept of conceiving the work of art.

The famous Buchi (Holes) and, from 1958, the birth of the Tagli (Slashes) that became iconic along with the Ambienti (Environments) made Fontana a reference for the new generations of the late 1950s and the avant garde movements of the 60s, from [the art review and gallery] Azimut, organised by Piero Manzoni and Enrico Castellani, up to the entire Zero group and the nouveaux realistes, including the young Yves Klein who became a firm friend of Fontana, then in his 60s.

[image5]

LŠ: Fontana was ahead of his time. He was “curating and creating” spatial experiences. How do you see his legacy today for contemporary artists?

LMB: Emerging from some of the themes of the Los Angeles and New York exhibitions is the pioneering element of his vision to be effectively recognised as one of the postwar protagonists with his gestures and works for the artistic dimension and especially for conception: for example, the title Spatial Concept for all works is one of the anticipatory elements of the last century. Fontana’s theme of the experience of space is fundamental: it has been about classical intent in architecture since the 1930s, but he was one of the founders of the environment when he asked the visitor to be part of the work. His legacy was strong as early as the 60s: think of the homage of environmental art artists and the perceptual and physical dimension of the viewer, American art of the 70s until Olafur Eliasson who uses energies, refractions today.

Fontana used a Wood’s lamp [a device that emits black light] in 1949 for environments and ceramic sculptures, and as early as 1951 for the immense neon signs Fonti di Energia (Energy Sources) he designed for the Italia 61 exposition in Turin. He was surprisingly interested in the use of television broadcasting to transmit contemporary art, anticipating all experimentation and even launching a Spatialist Manifesto for Television in 1952. A visionary with a vital forward-looking vision, Fontana was a pioneer of conceptual art and not just sculpture; his was a poetic response to more mental experimentation. He opened form and space to the gaze and physicality of the viewer. At the 2022 Venice Biennale, I curated an exhibition in which works by Antony Gormley and Fontana were seen in dialogue, showing great affinities. I also think of his Breathing Rooms. And in the environments, I think of the extraordinary assonances with some of Bruce Nauman’s Corridors, Tomás Saraceno’s extraordinary suspension of nuclei and Yona Friedman’s architecture. He was always in an extraordinary and happy “liberation” of sculpture in space beyond the traditional genres of the creative operation.

[image6]

LŠ: The exhibition at Hauser & Wirth’s New York gallery is titled Sculpture and, as the name indicates, it is focused on the artist’s sculptural and ceramic opus. While Fontana is known for Tagli, his sculptural practice was vital to his artistic development. It carried the artist’s experiments and prototypes in 3D materiality. The two exhibitions so far are also envisioned as a “reintroduction” of Fontana’s work to the US public. What were you keen for the audience to take away?

LMB: The aim has been to unveil Fontana through new eyes and works to expand his “inventiveness” and the richness of his research, which is often concealed by the emblematic nature of the cuts, which are, in their topicality, the contemporary icon that the world has clear. These Concetti Spaziali-Attese (Spatial Concepts-Expectations), however, come as the result and survey of more than 30 years of a coherent path strongly linked to Fontana “agitator of matter”, creator of matter, and gestural and conceptual sculptor. In this sense, we wanted to construct the exhibition’s path at Hauser & Wirth in New York, which also includes the clearly minimal metal sculptures and the series of ellipses that the public has rarely seen.

• Lucio Fontana: Sculpture, curated by Luca Massimo Barbero, in collaboration with the Fondazione Lucio Fontana, is at Hauser & Wirth New York until 4 February 2023.

[image15]

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)