Städel Museum, Frankfurt

19 September 2018 – 17 March 2019

by ANNA McNAY

Face to face. An appropriate title for an exhibition so largely comprised of portraits – among them a large proportion of self-portraits. For, surrounded by these canvases of Lotte Laserstein (1898-1993), one feels beset by myriad pairs of eyes. She is usually categorised as an artist of Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), alongside her male contemporaries Otto Dix, George Grosz and Christian Schad, but her style is really quite different from theirs – devoid of political satire and containing far more empathy, intimacy, and, dare I say it at the risk of sounding disingenuous, femininity.

[image4]

Laserstein grew up in a very female environment, with her mother, her sister, Käte, and her aunt and grandmother, following the death of her father in 1902. Fortunately, there was enough family money for both daughters to study and Laserstein was one of the first generation of women accepted into the Berlin Art Academy, in 1921 – two large charcoal drawings of male nudes evidence that she also attended life classes while there. Bear in mind that she was painting at the same time as, for example, the artists of the expressionist group, Die Brücke, and her style might seem a little old fashioned and venerating of art history – “more academy than avant garde”, as Kolja Reichert wrote in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung (23 September 2018). One hypothesis put forward by the exhibition texts is that, belonging to this first generation of educated female artists, she lacked the rebellious streak of many of her male contemporaries, wishing instead to prove her technical ability. Vermeer, for example, was one artist she openly declared to be a great influence on her, and aspects of the Dutch master’s style can be detected, especially, perhaps, in her choice of palette.

[image7]

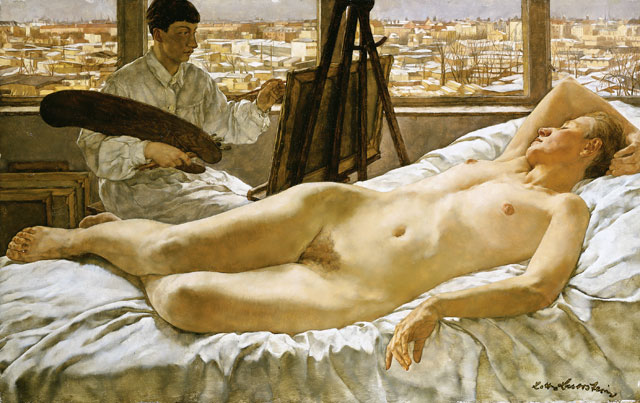

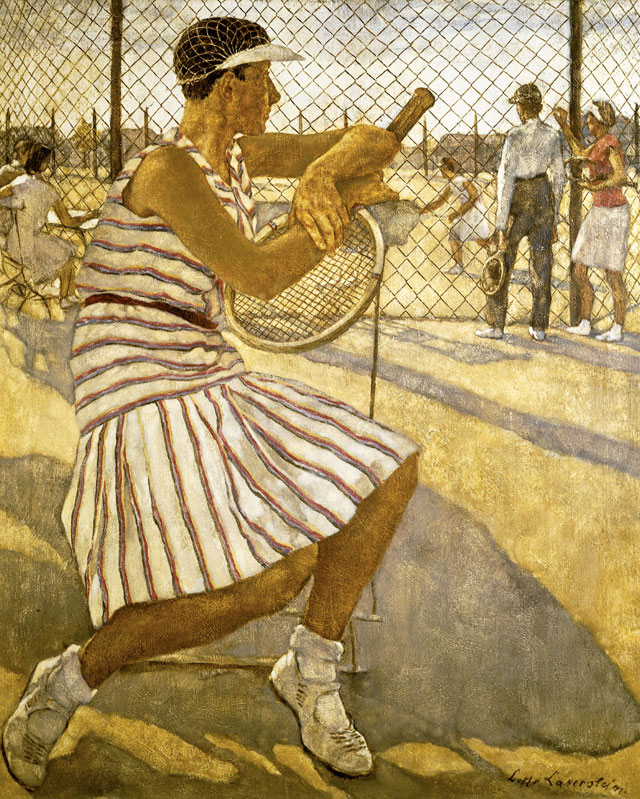

Nevertheless, Laserstein was not prosaic in her choice of subject, frequently depicting the “new woman”, androgynous and with short-cropped hair. Her close friend and favourite muse, Gertrud Rose, known as Traute, who modelled for 90% of Laserstein’s nudes, embodies this “type”. There has been repeated speculation over a lesbian relationship between the two women, but this seems, on the whole, to be unfounded – as well as somewhat irrelevant and an example of our contemporary classifications muddying those of the past. Not only was Traute happily married, but Laserstein’s sister, Käte, was in an openly lesbian relationship, so it seems unlikely that Laserstein should have remained in the closet, were this the case.

[image15]

As well as paintings of Traute, there are, as mentioned, a great number of self-portraits on display, as well as paintings in which Laserstein appears in the background, frequently wearing her painting shirt, as a kind of attribute. For example, In meinem Atelier (In my Studio) (1928) depicts Traute in a classical reclining Venus pose, set against the snowy rooftops of Wilmersdorf, Berlin. Between the foreground and background, the artist is present, standing – and working – at her easel. This is, in fact, an impossible composition, since, from the position in which Laserstein is standing, Traute would have had to appear in reverse. Additionally, while the painting itself is oil on board, in the picture, Laserstein is painting on canvas. Still, who is to deny a little artistic licence?

[image5]

This mirroring is, in fact, something Laserstein plays with in a number of her works, including also a later self-portrait in which she stands – somewhat poignantly, as will soon become clear – before her masterpiece Abend über Potsdam (Evening over Potsdam) (1930). In this example with Venus, however, the artist’s presence acts further to prevent the viewer from laying claim in his or her mind to the passive female (albeit androgynous) nude – since she is already “possessed”. By “possessed”, however, I don’t mean to suggest any sense of hierarchy or object-subject relationship – there is far more a sense of equality between the artist and her model, as also captured in Zwei Mädchen (Two Girls) (1927), which, with its close crop and studious but young and carefree poses, is my favourite work in the show.

Laserstein worked mainly with four basic sets of green-brown colours, and painted alla prima, largely with just one layer. Nevertheless, she was able to successfully create a convincing illusion of different materials, including, for example, leather and metal in Der Motorradfahrer (The Motorcyclist) (1929).

[image6]

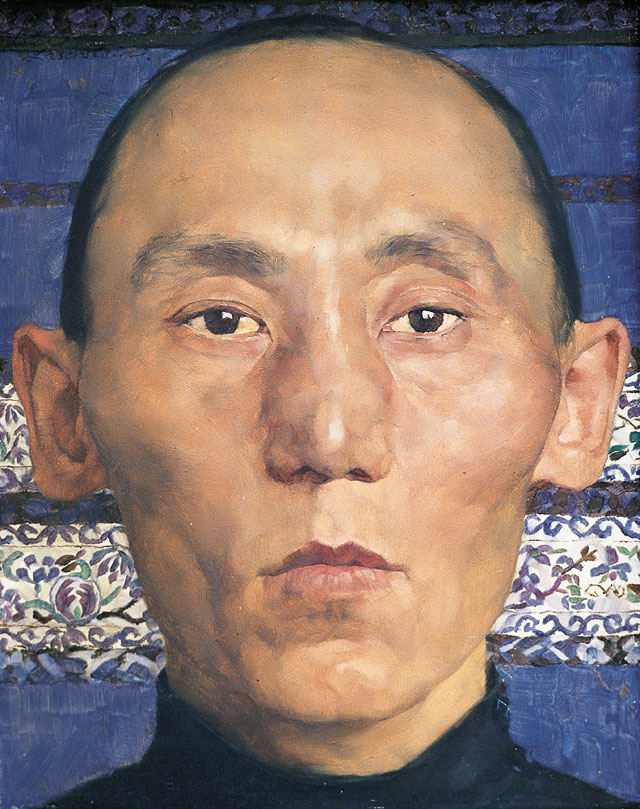

The hypnotic Russisches Mädchen mit Puderdose (Russian Girl with Compact) (1928), with its luxuriously rich crimson red, was one of the 25 finalists in a competition run by the cosmetics company Elida to find the most beautiful portrait of a woman in 1928. The model was the daughter of Laserstein’s Russian lodgers. In fact, she found many models among Russian exiles, following the 1917 revolution. This work and the later Junge mit Kasper-Puppe (Wolfgang Karger) (Boy with Kasper Puppet (Wolfgang Karger)) (1933) were both recently acquired by the Städel Museum, and it was around these that this long overdue exhibition was conceived.

This is the first time in Germany – outside Berlin – that Laserstein has been recognised with a proper retrospective. This comes as little surprise, however, given that she emigrated to Sweden in 1937, having been forbidden to work or exhibit in her own country, following the introduction of the Nuremberg race laws in 1935. Although a baptised Protestant, Laserstein had three Jewish grandparents, and was accordingly declared “three-quarter Jew” by the authorities when she turned to them for help. Cleverly – and luckily – Laserstein organised an exhibition in Stockholm, comprising much of her work, and, travelling there to “take it down”, simply stayed. Six months later, she married a Swede, so as to obtain citizenship, and she never returned to Berlin.

[image14]

This exhibition comprises 40 paintings and drawings, primarily from the Weimar period of the late-20s and early 30s. Laserstein’s life’s work as a whole comprises about 10,000 pieces, but many of these – with examples being the somewhat kitsch portraits of children on white backgrounds on display in the final space – were produced for clients in Sweden so as to earn a living, and weren’t what she would have wanted to be producing, either in terms of style or subject matter. “I can’t develop any further artistically,” she declared during this period. Accordingly – and, I believe, rightly – the curators have chosen to largely overlook these later works, excepting a few self-portraits, painted purely for herself, and thus enabling some element of continued experimentation.

[image2]

Laserstein’s key work is generally considered to be Abend über Potsdam (Evening over Potsdam) (1930), which has been likened by one of the curators, Elena Schroll, to a depiction of the Last Supper. Certainly there is a sense of impending depression (this was painted, quite literally, on the eve of the Depression), and the excitement of the “roaring 20s” has been replaced by an overt sense of melancholy. The five friends (painted after real-life friends of the artist, with Traute on the left-hand side – although the woman on the right, less of a patient model, actually has the legs of Traute beneath her own head and torso, and the dog, the least patient model of them all, was largely painted from a fur Laserstein had in her studio) seem no longer to know what to say to one another.

The logistics of producing the work were impressive, not just in terms of improvisation and problem-solving when it came to the models, but the one-metre-high by two-metres-wide canvas was transported by S-Bahn (overground train) from Berlin to a friend’s house with a roof terrace in Potsdam, and then back again to Berlin to be finished in Laserstein’s studio. Deservedly, that same year, Das Berliner Tageblatt declared: “Lotte Laserstein – this is a name to watch. The artist is one of the very best of the young generation of painters, her glittering path to success will be one to follow!”1 Schroll similarly describes Laserstein as a “rising star”, but she was sadly a rising star who had to flee her homeland and abandon her achievements long before reaching her zenith. With this presentation of highlights from her peak, there is hope that she might yet not be forgotten.

Reference

1. “Lotte Laserstein – diesen Namen wird man sich merken müssen. Die Künstlerin gehört zu den allerbesten der jungen Malergeneration, ihr glanzvoller Aufstieg wird zu verfolgen bleiben!”, trans. Anna McNay