Dundee Contemporary Arts, Dundee

8 December 2018 – 24 February 2019

by CHRISTIANA SPENS

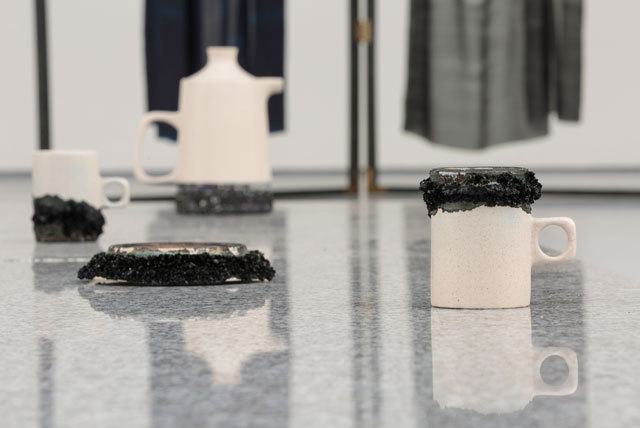

Tulips printed on to flowing, juice-stained fabric, a collection of small terracotta cups and pots growing black crystals, an image of a series of open doors – Lorna Macintyre: Pieces of You Are Here, at Dundee Contemporary Arts, presents, as the title suggests, an exploration into our relationships with objects, time and materiality. What is it to be here, to exist? What can the objects we carry, encounter and discard tell us about ourselves and each other?

As if inspecting the objects buried with a Viking, or left behind by a missing person, there is an eerie sense that we are piecing someone together from their material items, their treasures and ephemera. The gallery is filled with things, but absent of people (other than visitors); as a result, it begins to feel as if it is haunted by those whose relationships with the things are visible and yet invisible here. Who held the various teapots placed around the space? Who drank from the cups? Who arranged the flowers, walked through the empty hallway, touched the fabric? In many cases, it is the artist herself, but there is still a sense that she is summoning ghosts unnamed and unknown.

[image8]

Inspired by myriad influences, from poetry to archaeology and symbolism, Macintyre’s work delves into an exploration that is centrally about materiality: what it means to be in the physical world and interact with physical things, as thinking, feeling beings. When only material items remain, are we (or they) still there, somehow? Do things become haunted when they have been touched and held? Do we become haunted by things when we have carried them around for a long time? What does it mean to miss a thing?

While Pieces of You Are Here does not exactly answer any of these questions, it does provide a beautiful and multifaceted exploration of these themes and intuitions. The hanging onto a piece of clothing, for instance, when its owner has died or gone, the keeping of treasures from childhood, the photographing of spaces where one felt a certain way – these seemingly odd, default, sentimental things that humans often do come under a fresh spotlight, receive a new and helpful curation.

[image5]

Inspecting the various objects and artworks becomes a meditation on the passing of time and, as such, turns to the morbid: there is a sense that the “things” are substitutes or even fetishisations of people or feelings that are now gone. It is as if the objects hold life and sensation, and even memory, longer than the people who interacted with them. There is, therefore, an atmosphere of loss: if these things weren’t here, were its people? If you don’t leave behind traces and belongings, things you have touched, then were you here, either? There is a feeling that memory and sense have slipped away – are always slipping away – leaving these shells, with our physical traces having changed them, but only incrementally. Objects, Macintyre seems to imply, retain memory longer than people do: we are pushed towards a morbid acceptance of being ephemeral, fleeting and physical.

[image3]

One highlight of the exhibition is a photograph of an archaeological artefact from the collection of the nearby McManus Art Gallery and Museum, a small terracotta tile excavated from the Roman Fort in Abernethy (just north of Dundee), which shows a pawprint made by a dog who walked across the clay surface as it was drying, hundreds of years ago. Macintyre was compelled to include this image of an artefact as a way of showing the strange juxtapositions of materiality and time, and the recording or preservation of both. As she says in the exhibition’s accompanying notes: “There’s a poetic distinction between the permanence of this material and the lightness of the movement across it – it forms a kind of photograph in a way – a trapping of a moment in time. This is something I’m trying to build into the works in the show as a whole – this contrast between the solidity of objects and the fleeting presence of light, gesture, accident or imprint upon them.”

This exploration of materiality and the tangible connections between things is further developed through a fluid, holistic approach to practice that sees Macintyre producing works that connect with one another through their processes, subject matters and symbolism. In one work, for instance, a photographic image of water is printed on silk, which has then been dyed a deep indigo before being soaked in the liquid it depicts: the material used to make the work is also its subject matter. The thing that is represented by the artist is part of the process of that representation; there is an alchemical, magical quality to these subtle transgressions and blurred boundaries between reality and representation, quietly dissolving the presumed distinctions between the two.

[image7]

In another group of works, three blue cyanotype prints, offcuts from the silk photographs were dropped on to chemically treated paper and then exposed to sunlight over several months. Here, the methods used to create photographs are deconstructed to show the almost archaeological nature of the method: the way in which time is captured in paper, through processes that rely on elemental cycles and structures. We cannot distinguish art from life and especially the material world in which we live. We cannot separate ourselves, either. While, initially, this emphasis on the fleeting nature of our lives may seem morbid, with more reflection it becomes positive. We do not only lose things to time; we also gain. We may lose specific sensations, but with time and physical processes, these moments are integrated into the world again and transformed into new things.

The black crystals that grow from teapots and cups are testament to this: employing the same chemical processes used in the cyanotype paper-coating process, Macintyre grew these in her studio. They vary in spikiness and density according to the season in which they emerged, and so record the conditions, invisible now, under which they grew.

In an almost hidden back room of the gallery, finally, is a short film depicting Macintyre’s newborn baby’s hand reaching out and clenching her fist – again, there is a notable absence of noise or context. Shown in this way, the baby, this new life, grows as crystals and trees and artworks do: responding to and absorbing her environment. Ultimately, Pieces of You Are Here is a profoundly positive exhibition. It shows us that, although time is fleeting and people are vulnerable, we nevertheless belong in this strange, physical, alchemical world in which we are part of a continuous series of transformations, integrations and processes that, when considered with some degree of detachment, is quite beautiful.