by A WILL BROWN

Liz Magic Laser, who was born in 1981 in New York, is a multimedia artist who works mostly in film and video, often making multichannel installations. Laser’s work focuses on interrogating various forms of information distribution and sharing, such as televised news media, internet memes, theatrical performance and newspapers. She is also known for making live performances interspersed with pre-authored multimedia components that challenge the very nature of video and the regularly used editorial and compositional tools that artists and media distributors rely on. With an uncommonly direct, yet subtly authored, series of critical compositions, Laser’s work constantly brings new and provocative juxtapositions to the fore.

A Will Brown: Let’s begin with one of your newest works, The Thought Leader (2015), a single-channel video in which a child actor delivers a monologue you adapted from Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s 1864 novella Notes from the Underground. The words become confounding – somehow heavier and lighter simultaneously – when performed by a child. Why did you cast a child in the central role?

Liz Magic Laser: The child is typically used as an emblem of the future, of hope and change. I felt that a 10-year-old would be a perversely well-suited spokesman for my anti-idealistic TED talk. There’s an optimism underlying most TED talks that implies that one’s individual aggrandisement can contribute to the greater good of all. Having a child deliver Dostoyevsky’s words may be jarring at first, but I think the novelist’s critique is so applicable to TED that it starts to make sense. I chose Notes from the Underground as the basis for my script because it provided an uncomfortable and revealing counterpoint to TED’s idealism. Dostoyevsky wrote his novella as a direct response to the socialist ideal of enlightened self-interest that was promoted by Nikolai Chernyshevsky in his 1863 novel What Is to Be Done?. “It is better to do nothing!” was Dostoyevsky’s provocative response to the utopian fantasy that an individual’s selfish pursuits could benefit the common good. More than 150 years later, Dostoyevsky’s nihilistic critique still holds water when applied to the current techno-utopian incarnation of enlightened self-interest.

AWB: It’s also interesting when your protagonist uses antiquated words or phrases – for example: “You disgrace yourself in the marketplace.” How did you adapt the language for this script, and why did you leave in some of these older turns of phrase that may not make sense to a contemporary audience?

LML: I often look for potential puns like this in the material I’m culling. When Dostoyevsky talks about the “marketplace”, he is referring to an open-air market for groceries and wares that was the central public hub in his day. Using that line in the TED context, I was repurposing it to refer to the financial market. I do get a kick out of reviving antiquated colloquialisms, but try to use them in a way that makes sense even if it gives you a moment of pause. I intend this as an alienating or double-take effect rather than an obfuscating one.

My method of adapting source texts usually involves extracting sentences and sentence fragments, altering the language in places, replacing pronouns frequently and montaging the material together along with other source material and some original writing. I wrote The Thought Leader script by extracting and adapting lines and ideas primarily from Notes from the Underground. I also culled a few lines from David Foster Wallace's essay about Notes from the Underground, as well as from Jeremy Donovan’s manual, How to Deliver a TED Talk, which contains some oddly existentialist moments.

AWB: The work also has a strong satirical thread, analysing the all-too-present TED talk, a forum, or brand rather, that has become more and more tiresome and sprawling. TED talks feel as if they are more for the speaker than anyone else, a self-indulgent, unspecific platform that often doesn’t offer anything concrete. For you, what does this work tell us about TED and similar platforms?

LML: Over the past few years, I’ve focused on how techniques from the theatre are used by politicians to optimise the persuasive impact of their speeches. The increasing popularity of TED talks caught my attention because TED seemed to highlight and directly enhance the importance of public speaking skills across a wide range of professions. I see the TED talk as a highly cultivated performance of one’s hyper-professional yet “all too human” self.

AWB: Amazingly, the TEDBlog reviewed your project The Thought Leader in relation to its own activities. Did it miss the point, or offer anything substantive to your ideas? That is an interesting moment I imagine.

LML: I corresponded with the editor of that piece and not the writer, but I’m pretty sure the point was not lost on either of them. I was thrilled that they wrote about and posted the video. I’m interested in reaching a wider audience, so delivering my perverse TED talk through the platform it was commenting on felt like a coup. Moments such as that make me feel there is potential to align my approach with the way early photomontage artists such as John Heartfield and Hannah Höch used magazines, the dominant form of mass communication in their era. Similarly, I’m interested in dissecting and reconstituting current communication methods and rhetorical forms such as the TED talk.

AWB: Artist Simon Denny has made a body of installation-based work about the TED talk and organisation, which was used as a platform for what he called TEDxVaduz, which was held at the Kunstmuseum in Liechtenstein in 2013. Have you seen this work? I find some resonance with The Thought Leader.

LML: I’m a fan of Simon’s work, but didn’t know about his TED project until mine was underway and someone mentioned it. I think our critiques of TED are like-minded, but our approaches are very different. Early on in my scriptwriting process, I came across Benjamin Bratton’s TEDx talk, We need to talk about TED, which was so brilliant and lucid in its attack on TED, it led me to scrap my original script.

AWB: I think what you’ve done, and continue to do, in interrogating gesture, behaviour, repetition, movement and speech patterns is brilliant. Where does your interest in behaviour come from, and when did you start working with body language in relation to popular news media and political or formal speeches?

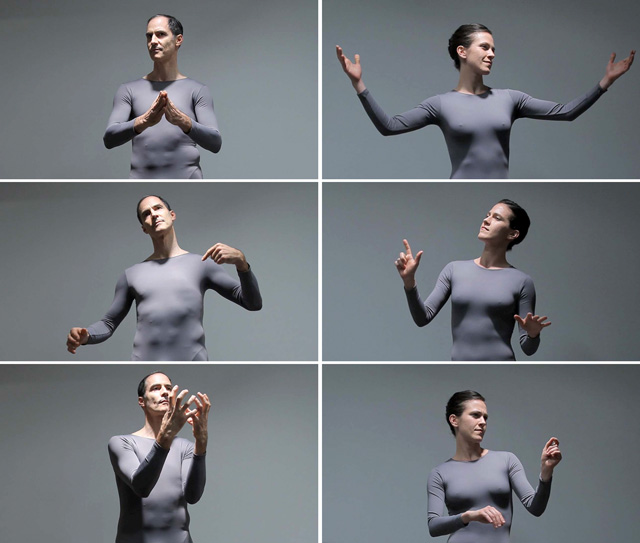

LML: I think my own uneasiness with performing was responsible for my initial interest in public speaking and the increasing importance of performance skills in everyday life. When I saw President Obama’s 2012 State of the Union Address, his gestures were so active and precise that it reminded me of research I had done on François Delsarte, who developed oratorical theories and exercises in the early 19th century. Delsarte coached actors, statesmen, preachers and lawyers. His theories seem to presage scientific management and the drive to maximise the efficiency of every gesture performed in the workplace and on the theatrical or political stage. I wanted to show the evolution of the politician’s performance so I searched through past State of the Union Addresses and imagined I’d find a nice starting point for virtuosic gesticulation with Ronald Reagan’s speeches. I was surprised to find that Reagan barely moved his hands, which were glued to his script. I found that static hands and close-up framing was the convention in all the formal speeches of his predecessors, at least those that were televised. It turns out that HW Bush was the first to bring gestures back into his formal speeches. In the end, I worked with two dancers, Alan Good and Cori Kresge, to make The Digital Face, juxtaposing the gestural display from HW’s first State of the Union Address with Obama’s most recent one at the time in 2012.

AWB: Where does a project usually begin for you in terms of ideas?

LML: My ideas usually start with a curiosity about the set design of places such as the television news studio and the behaviours these scenarios perpetuate. I often have a few types of places I’m interested in working with, and then struggle to find the script that will produce a generative friction between activity and context. Ideally, the place and the script will serve as catalysts for one another, unearthing the manipulative nuances of each.

AWB: As digital media becomes increasingly pervasive and sprawling, how is the performance of power and the behaviour of political control changing? I wonder if the repetitive gestures – obsessive looking at and checking of devices – now so prevalent, are bending not only our attention spans, but the ways in which we are able to receive meaningful content and ideas. When Nicolas Bourriaud gave a lecture a few years ago at Banff Centre, he spoke very specifically about the “swipe” gesture, up, down, side to side, and how that is changing our very basic interactions with space and ideas, wondering what it means when we all become the conductor of our own experience. Would you agree?

LML: I think this “swiping” gesture you mention probably imparts a false sense of control. In my view, the operation of power is becoming increasingly bureaucratic in its execution. Politicians and business leaders contract a variety of advisers, market researchers and PR consultants to engineer both their policies and posture for maximum appeal.

AWB: When did you begin working with performance, documentation and already produced content, mostly video, as enmeshed components?

LML: In 2006, I gradually transitioned from photography to performance-based video. As a photographer, I had been interested in using the camera as an active participant from the start.

AWB: Do you have a background in dance, or choreography more specifically?

LML: Yes, my mother, Wendy Osserman, is a choreographer. I quite literally grew up in her rehearsal space and would photograph her company for flyers and press, eventually collaborating with her dancers as well. Also, they would take part in my staged tableau-style photographs, and I even performed in some of their choreography. As a photographer, I confronted the issue of mediating performance through the camera as a teenager, which definitely influenced my hybrid approach to multi-camera live-feed performance.

AWB: Watching The Digital Face, from 2012, I was immediately cognisant that I was watching a reperformance of President Obama’s style of oratorical gesture. In a description of the work, you noted that George HW Bush was the first to use gesture in this way. I can’t imagine a political or presidential speech without gesture. Are you finding that there are newer sets of visual, gestural or behavioural strategies emerging for politicians now that we haven’t yet seen fully? What’s the next phase of rhetoric – perhaps an increased emotional or more visceral behavioural strategy?

LML: Presidents before HW did gesticulate in debates and combative scenarios, but not during formal speeches such as the State of the Union or Inaugural Address.

In the recent Republican debates, I’ve seen a trend toward brash spontaneity in both rhetoric and facial expression, as well as a lot of dismissive hand gestures and expressions. Naturally, Donald Trump is at the forefront of this irreverent behavioural strategy. I think this trend and its effectiveness was probably informed by social media. The rehearsed behaviour of politicians now seems to be emulating the immediacy of the tweet.

AWB: Do you strive to work with the same actors and performers in your works? I could imagine that communicating what you envision for them is a challenge at times. What does the process of casting and working with your performers look like?

LML: An ensemble cast has coalesced around certain ongoing projects, such as Flight and The Living Newspaper series. Initially, I only worked with actors I met organically through friends, working on a play, or at a barbecue. I did my first more professional-style casting in 2011 for my Performa commission. Two actors I had worked with frequently, Liz Micek and Max Woertendyke, taught me how to conduct the audition interviews, and I’ve done a number of castings like that since. However, my first course of action for finding performers or other types of professionals to work with continues to be word of mouth. I’ve often sought out non-actors – journalists, speech coaches, market researchers and figure skaters – as well as child actors. I usually write up emails with briefs on the project that I, or the institution I’m working with, send out to people asking, for instance, if they know a political strategist who might participate in an unusual project. Most recently, when I was casting for figure skaters for a commission with Mercer Union in Toronto, it sent my casting call brief out to a bunch of skating clubs and schools. For auditions, the curator, Georgina Jackson, and I went around to a half dozen rinks to meet people and see them skate.

AWB: A number of your works, in particular From North Carolina to South Korea, Like You and I Feel Your Pain, function across multiple platforms and seem to offer various time signatures, as though they could occur repeatedly, only needing the necessary set of conditions to take place. I’m taken with this sense of flexibility and of continuity, yet the firm sense of completion that simultaneously takes place in your work. Do you consider some of these projects as reperformable or restageable? Can you speak to the openness of working with performance and staging, improvisation and deliberation?

LML: I need elements of both improvisation and deliberation. I’m interested in throwing a well-rehearsed script into a precarious scenario where improvisation will become vital. In some cases this becomes an extreme sports-style challenge for my actors. For Flight, the actors had to provoke and respond to spectators while rapidly performing scripted lines and risky fight choreography. That performance originally took place at MoMA PS1 and was restaged the following year on the red TKTS staircase in Times Square, New York. I’ve restaged other performances as well, for instance Stand Behind Me was the international version of The Digital Face. I think of it more as a new incarnation of an earlier project, though. Since the subject matter of much of my work is topical, it’s only fitting that the scenario and script are updated when a premise is restaged.

AWB: In one of your newest videos, Kiss and Cry (2015), you explore the history of the idea of children as a group needing both protection and control. For me, what is most difficult to break away from here is the notion of children as small, yet unformed, versions of who they will become. But perhaps their child and adult selves can be distinct somehow. What do you think?

LML: I was quite taken with these particular children, Axel and Anna MacKenzie, with their strong personalities, minds and athletic abilities, and I did wonder about who they will become. That said, I was interested in using the child as more of an archetype in the video and didn’t expect these questions to be sparked. In any case, I think it’s a mixture of the two notions of development you describe. There are usually personality traits and behaviours that carry on from childhood to adulthood. I’m perhaps more intrigued by what makes the child self and the adult self distinct from one another. Children are not fully acculturated yet, inhibitions and self-consciousness haven’t fully taken hold; perhaps therein lies the distinction.

AWB: Why did you choose two child ice skaters as the subjects of Kiss and Cry? What other kinds of sports or activities were you thinking about focusing on?

LML: During my first site visit to Toronto last February (2015), I heard about the live-editing techniques involved in filming ice hockey and my interest was piqued. My first script for the ice rink was a futuristic child custody dispute on ice that mixed the ice hockey scenario and Olympic figure skating with a courtroom drama. I was thinking about family values rhetoric and looking back at a performative lecture I did for a Michael Jackson-themed event. When my friend, artist Simone Leigh, curated the programme at Recess, New York City, in 2010, I compared photos of child labourers by Lewis Hine to photos of Michael Jackson, weaving a polemic argument on the cultural construction of childhood innocence. I claimed that this idea of the innocent child grew out of a rightwing reaction against the sexual libertarianism of the 60s.

In early 2015, after working with child actors for the first time for The Thought Leaderand My Mind is My Own, I became interested in dealing more directly with the child as an emblem of the future. Around this time, I was also discussing the culture wars controversy surrounding the Robert Mapplethorpe show at the Cincinnati Contemporary Arts Center with the curator there, Steven Matijcio, so I had a heightened sensitivity to all the political rhetoric about “protecting our children”. At first, my ideas about the child seemed like an odd match for the competitive ice skating scenario, but it started to click once I found Anna and Axel and their mother and coach, Marie, and was able to bring their athletic training into context with parenting. Figure skating seemed to tap into fantasies of childhood innocence, of being a star or a princess, as well as conjuring the vicarious sensation of freedom, flying, soaring. Simultaneously, it is physically demanding and psychologically rigorous work. Outsiders to the sport might judge the training to be inappropriately gruelling for children to endure. Competitive figure skating seemed to encapsulate contradictory visions of the child that became generative for the conflicting ideas that I wanted to explore.

AWB: Around 12 minutes in, when the little girl begins to repeat her mantra of “You’re going to be all right, you’re going to be fine” to herself, the work takes on a new kind of intensity. What is that mantra about for you? How does it open up the philosophical questions you are asking about children and development?

LML: I asked Anna and Axel what they say to themselves in their heads when they’re about to execute their most difficult moves, and this mantra emerged, which I asked them to vocalise. I see this mantra as the beginning of self-reliance, of the child parenting herself. A sort of splitting takes place where one self reassures the other scared self.

AWB: What artists have been significant touchstones for you in your career? Who do you feel like you are in direct dialogue with currently?

LML: In my early 20s it was Paul McCarthy, Martha Rosler, Janine Antoni and Andrea Fraser; and a bit later, perhaps, Yvonne Rainer, Sharon Hayes and Steve McQueen. More recently, friends whose work I feel a dialogue with include David Levine, Dafna Maimon, Michael Portnoy, Ariana Reines, Josh Kline and Becca Albee.

AWB: Your 2013 work Absolute Event seems to embody most of the strategies you use in your work. Forgive the long list, but it’s a complex work that includes performance, repetition, installation, screenwriting, dance, humour, political rhetorical critique, and so on. The use of all of these, and many other elements, creates an amazing series of transitions, in which the audience and the viewer of the documentation and resulting video slips between registers of awareness and meaning. One is often left to interpret what is unfolding with an improvisational sense, never quite knowing what to expect next. This would seem to create a much more engaged audience, somehow complicit in the process of both editing and directing. Would you agree?

LML: I try to create that potential for active engagement in most of my work, but Absolute Event was perhaps more open to interference from the audience than other performances I’ve done. One audience participant derailed the whole performance for five minutes with outlandish statements about “flaming placentas”, and many people asked if he was a performer in the piece. It turned out that he was a philosophy teacher at the School of Visual Arts [where Magic Laser teaches], a colleague I hadn’t met before, but whom I met subsequently.

AWB: How visible were all of the elements to those in the gallery? From what I understand, you were editing the performance live, which you do elsewhere in your work. Is it akin to live news or sportscasting, and what is that process like?

LML: I’m definitely taking a page out of the broadcast television handbook. I used a TV news studio on a few occasions for projects in Sweden and Houston, Texas, where I worked with communications school students and their teachers; and have learned how to compose scripts with live editing cues. Television scripts are typically printed on light blue paper, a convention I’ve adopted, and the scripts from Absolute Event were left out on the “control room” table along with all the video and audio channel mixers – so, yes, all the technical equipment for the live-broadcast television process became part of the installation at the Paula Cooper Gallery after the performance that I edited live, while cuing the actor who played the political strategist as well as the camera people.

AWB: What are you working on now in the studio that you can tell me about?

LML: I have just moved into a new studio in Gowanus, Brooklyn, and am starting to work on my first survey show at Kunstverein Göttingen, Germany, which will take place in March where I will produce a new installation through a series of workshops with local high school students. The functional set, a news bureau meets primal scream therapy room, will serve as a site for the teenagers to predict future world events.

Liz Magic Laser: Kiss and Cry is at Mercer Union, Toronto, Canada until 23 January 2016.