by BETH WILLIAMSON

Libby Heaney is a rare combination of artist and physicist. Experimenting with quantum computing to create wondrous environments, in her latest exhibition, Ent- at Schering Stiftung in Berlin, Heaney draws on the monstrous worlds of Hieronymus Bosch’s famous triptych The Garden of Earthly Delights (1490-1500), specifically the central panel, to create hybrid creatures and new worlds. Quantum computing and its concepts are difficult, but Heaney describes them with ease in this interview and explains how her artistic practice uses quantum to offer new, non-binary perspectives on the world.

Heaney spoke to Studio International at the start of Ent-. The following is an edited extract of that interview.

Beth Williamson: You trained as quantum physicist before you trained as an artist. That seems like quite a leap. How did that come about?

Libby Heaney: When I was at school, art was by far my favourite subject. I would have happily, gone to art school but I was also very good at physics and maths. My teachers, family and friends advised me to study what they considered to be a more serious subject, like physics. I come from a working-class background and was the first generation of my family to go to university. They were really worried about me studying art because I’d never make any money, so suggested I study what they considered a serious subject, although I consider art to be serious. So, I did that and was always making art while I was at university. I did a PhD and five years of post-doc study and really fell in love with quantum physics: it’s probably the most art-like area of science because it really requires a big leap in imagination. It’s not connected to how we experience the world every day. You need mathematics to really understand the mechanics of it, but you need a lot of creativity and imagination to play and do research in it as I was doing. Throughout this period, I was also saving money to go to art school. Eventually, I had enough money and went to Central St Martins. So, it was always on the cards. I just took a detour, but I’m glad I did.

[image2]

BW: Can you tell me something about quantum and why it’s important? I’m thinking of those tricky concepts such as superposition and entanglement that you deal with in your practice every day and are quite difficult for the rest of us to understand.

LH: They’re almost magical. It’s almost like quantum physics is a belief system. Experiments show that something is going on that relates to the mathematical models of quantum physics, but to really accept them and believe them, you have to take this leap of faith, I suppose.

Superposition describes quantum particles (it could be atoms, photons, which are particles of light, or molecules) existing in more than one state at the same time. It could be that an atom is in this room and in another room at the same time. The Chinese scientist Jian-Wei Pan has used quantum superposition and entanglement to teleport matter into space. People have been demonstrating this plurality at the heart of matter for a long time.

Entanglement is when you take superposition to two or more particles. They can be become entangled and lose their own identity, their own individuality and become one, even if they are very far apart. For us, it’s very hard to understand. I’ve been playing with slime. When we play with slime there is an object there, but it doesn’t necessarily have its own fixed properties. We can smear it out in space, it has morphing qualities, it is shapeshifting and can mould to containers and so on. That reminds me of superposition.

[image3]

BW: You said earlier that you were a scientific researcher before you were an artist and I wonder what parallels you see between scientific research and artistic research? Are they two completely different beasts or do they have some fundamental things in common?

LH: Of course, they do, but there are moments of resonance and dissonance between them. The moments of resonance are the creative process. Generally, in the arts we are looking for something that hasn’t been done in the same way before, something that you can contribute, that’s slightly different. In the sciences, in order to publish a research paper, it has to be new research too. You ideate around your field to allow you to take those next steps into new territory. But the process of getting there is very different between the two. In science, you are really on railroad tracks. I am a mathematician. For me, it’s knowing the field, knowing the mathematics as an architecture or framework, having the idea and discovering the mathematics to take us forward into new knowledge. Because you are on these railroad tracks, working within the correct way of doing mathematics, you hopefully come up with a result that is meaningful.

[image4]

BW: That fits with what is already there?

LH: Exactly, and experimental scientists could go to the laboratory and test that result and verify if it corresponds to reality, or not. In art, instead of being on this railroad track, it’s more like a giant spider’s web and we are looking to create metaphors or meanings in many different ways, bringing in diverse pieces of knowledge, a bit like a magpie. We bring in personal ideas and subjective experience, whereas in science you try to keep yourself out of it. I don’t think that’s possible, but the idea is to take yourself out of it, whereas in art what we create is just this giant self-portrait.

BW: I have been thinking about how artists often use drawing or sketching as a starting point for their practice, regardless of their working medium. Do you do that, or do you have a different starting point, and how does that fit with what you create in the end?

LH: Absolutely! You can see here lots of paintings [shows paintings]. These are ideating right at the start. There are words and drawings, connections to other artworks, it’s like brain-mapping. These aren’t how the work was in the end, but suggesting, storyboarding. It’s so different to what came out in the end, but elements of the work appear. At the same time, I’m working with code as well and that is a very different process. We spoke about the process of making science, and you are on the railroad track, when I’m working with quantum code, I am looking to create an aesthetic that I wouldn’t be able to do without quantum algorithms. That was going back to science, thinking about what I knew about quantum physics and how to develop the visual around that. I have parallel methods while I’m creating these works.

BW: You are bouncing backwards and forwards between the two?

LH: Exactly. There is an iterative process and at some point, I start sketching on the computer, not just with code, which is text, but within programmes called Unity and Blender, 3D programmes that are a bit more fluid.

[image5]

BW: Thinking about your new exhibition Ent- in Berlin, the exhibition flyer says it explores the transformative changes in quantum computing that are expected to have an impact on the future of everyday life. Can you explain the ideas behind Ent-? Where does the name come from, for example, and what are you are trying to address in the work?

LH: Ent- is “ent” followed by a hyphen, so it is a word that is waiting to be finished by audience members. I speak a bit of German (I did my Erasmus exchange there in 2003) and I remembered that “ent” is a prefix in German, that means a start of an action or a separation. The work was also commissioned by Light Art Space, a Berlin-based art foundation. I thought that ent suggests where humanity is with quantum computing today – We are right at the beginning. German words such as entstehen and entdeken – to arise and to discover – are where we are with quantum computing. It invites audiences to finish the piece. In English, because the work is coming to the Arebyte Gallery in London with additional pieces, there is entanglement, which is a phenomenon within quantum computing. Entropy is very important within Bosch as well. Words such as “enter” – enter on the keyboard, enter the black box, enter that world. Enter is also a return to the beginning. I like playing with language and the word embodies what the work is about and maybe elicits some confusion because audience members are trying to work how to finish it, but that is where we are with quantum computing.

I’ve been thinking about the double-edged potential of quantum computing. How it is being developed by big tech companies suggests it will mainly be used for profitmaking endeavours to further a surveillance capitalist regime. Social media platforms extract data from us in order to then advertise to us, or polarise us in relation to elections and so on, which, in my mind is not desirable. I’ve just discovered that quantum warfare is a new area, which is quite disturbing given what is happening with Ukraine and Russia right now. Part of the work in Ent- collapses, becomes desaturated and all the forms are quite ruinous, a warning like Bosch’s hell, about the potential downsides of quantum computing. On the other hand, these concepts I’ve already mentioned, such as superposition and entanglement, could lead to new ways of thinking about our position in the world and our connections to others. We could start to move away from binary thinking into a world where we consider our connection to each other and our environment much more.

[image6]

BW: That brings me to my next questions and starting to raise some ethical questions about how we think about things and how understanding a bit about quantum could potentially shift that?

LH: Absolutely. In the west we have this neoliberal mindset and it’s all centred around the individual and has been for a long time, and by thinking through quantum concepts, we could unpick some of these hierarchies and biases that we live within. In terms of ethics, because quantum physics is a non-local theory meaning entities can still be entangled even if they are far apart, we could start to think through a non-local responsibility.

BW: So, it is about operating in networks?

LH: Networks, but where the idea of an individual becomes irrelevant. When I am using quantum computers, I am building these entangled states within the quantum computer using a program and then the idea of an individual qubit [a quantum bit in computing] becomes irrelevant. And the data from these entangled states are processing the animations in my work.

BW: Which takes us to collective responsibility?

LH: Yes, but in a much stronger way than in other theories that deal with relations.

BW: Following on from what you’ve just been talking about, I want to bring in Paul Preciado’s book Can the Monster Speak? It’s about his experience as a transgender man, and he mentions quantum and references the ideas of Bruno Latour and Thomas Kuhn and Kuhn’s book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962) and the idea of paradigm shifts in how we think about things. He talks about facts “landing” and explains the idea that a hydroplane cannot land at Orly airport, because there is no water, and a quantum cannot land in Newton’s physics. It strikes me that your work is making a similar sort of commentary in a different way.

LH: Absolutely. I really like this question. I think this idea of facts landing is really nice. It just speaks to me about incompatibilities. I haven’t read the book.

BW: Let me read you just one sentence.

LH: I’d love that.

BW: He says: “An epistemology represents a closure of our cognitive system that not only offers answers to our questions, but determines the very questions that we can pose”.1 For me, that makes sense that quantum is making us ask different sorts of questions?

LH: Absolutely, and it is also almost an open theory because the notion of truth, of facts, even in quantum, becomes irrelevant. Entities in quantum physics can exist in a huge multiplicity and that is contextual on how they are observed. Things reveal different properties or change or shapeshift based on how they form relations with other things. There is no ultimate truth. They adapt and reconfigure in a performative sense. Therefore, just by engaging with quantum, we have to reconfigure the questions we ask, and mindset, to move away from the Newtonian and the rigidness in which we have found ourselves. It is interesting that a trans man is thinking of quantum because I feel that quantum thinking is very queer, because it moves into a hybrid space. There is no one state of being. It’s an explosion of potential and possibilities.

[image7]

BW: Let’s return to Ent- and its relationship to Bosch’s famous triptych The Garden of Earthly Delights. Can you say something about that? It is interesting that you’ve looked at work that is about 500 years old. You have gone from a traditional medium – you are using watercolour painting, too, as part of your process – then using this advanced technology to create the work. Can you say something about that process and about why Bosch’s work was so important for you?

LH: I’ve worked with Bosch before with his triptych The Last Judgment, thinking about human bodies in terms of machine-learning and which bodies are acceptable and which are not. Bosch was already on my mind when I came to Ent-. There are multiple reasons why I chose to work with Bosch. The ideas I want to discuss around quantum computing are quite difficult. Attaching them to something as well known as The Garden of Earthly Delights allows people to access the themes through Bosch as opposed to through quantum computing. So, I see it as a doorhandle into the work. Ent- is based around the central panel, which is situated between paradise, or heaven, and hell. So, even at its simplest it speaks about how the future of quantum computing might go forward.

Bosch painted that work just before Copernicus changed the world view by saying the sun was at the centre of the solar system, as opposed to the Earth, and it was at the start of the Renaissance. I think there will be a paradigm shift because of quantum computing. In relation to the hybrid creatures, the idea of hybridity was outside the dominant world view in Bosch’s time, the demons in his paintings weren’t in God’s order. What I am suggesting is that if you follow the logic of quantum and superposition and entanglement, it does take you outside the logic of where we are today. So, we go from the usual taxonomies and categories that can be quite biased or prejudiced, or value the human over the natural, and so on, into something that is more mixed and hybrid.

BW: You’ve mentioned the dangers implicit in new technologies. How do you hope Ent- brings that out for audiences?

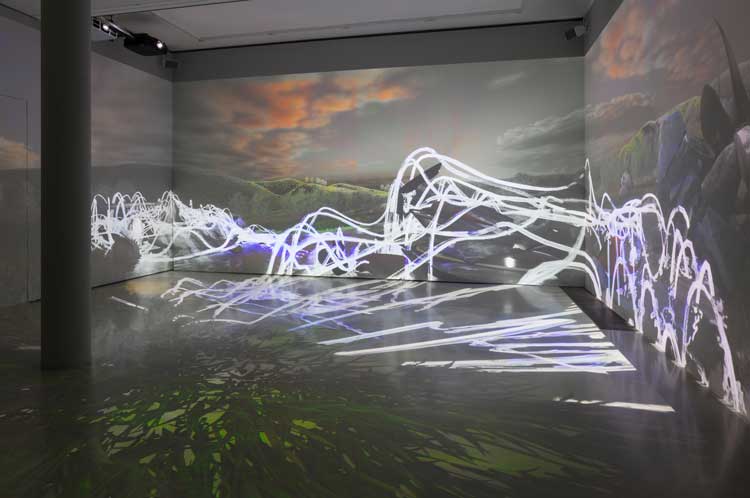

LH: I wanted to capture that through the work. There are three scenes. There is the scene where you fall through the sky out of giant quantum computer with tentacles extending, which can be a symbol of entanglement but also a symbol of creeping technology. That scene is quite uplifting. Then you enter an architectural world, into a dark cave with more tentacles. The darkness and sounds are quite uneasy at this point. I’m hoping to create an emotional experience. In my architectural and underwater scene, everything gradually becomes darker and both of those scenes collapse at a random point. If you stay in the work for a long time then you will see that sometimes a scene might be four minutes long and other times it might be two minutes. Sometimes it pushes back on the audience and won’t let them see the bit they saw before. At that point, the worlds desaturate and become ruins and these tentacles creep over the top of them and underwater the forms explode. It becomes more chilling and references Bosch’s hellscapes and the chaos, destruction and greyness. It’s emotional and the audience members become bodies within Bosch’s work, experiencing these changes in the environment.

[image8]

BW: How have audiences experienced Ent-? Do you know?

LH: One woman at the opening told me she really wanted to dance in there, but she didn’t because there were other people present. I found that interesting because the idea of using the 360-degree projection was to place the audiences within that world. Our bodies become the bodies in Bosch’s work. How can these quantum animations entangle our bodies with the work? If she felt that she wanted to move, that’s some sort of entanglement, she’s reacting.

BW: I felt dizzy in Ent-!

LH: Well, that’s the point of it, to destabilise you. Maybe the dizziness is the dizziness we feel when we encounter the new, new technology, new futures that quantum computing might lead to. In future works, I’d love to play with that sensation of destabilisation, or dizziness.

BW: I wanted to ask about the religious context to Ent- through the reference to Bosch and how you relate to that in the work. I’m thinking also of your other works such as The Whole Earth Chanting, where you collaborated with musicians. They may not be explicitly religious, but there is a spiritual aspect to them.

LH: Absolutely. The musician Nabihah Iqbal, whom I worked with on The Whole Earth Chanting, also did the sound for Ent- and we have another project together. She is a long-time collaborator of mine. One of the strategies I have in my work is to use the technologies against their predominant means. So, The Whole Earth Chanting is using machine-learning to create human and non-human voices. The computer learns how to replicate these voices but creates hybrid humans, and birds, and sounds quite unusual. Scientists or technologists wouldn’t use it in this way; they would use it to copy what already exists, but I’m using it to find new potentials or subvert its predominant capitalist use. One of the questions I have in my work, in The Whole Earth Chanting and in Ent-, is how technology can be used to bring people together and momentarily form new expressions of collective identity. Chanting is a really good way of bringing people together. We start to feel something beyond the everyday. Using this 360-degree projection in the space in Ent- where you have sounds and lights moving around you, in a very different way but still through senses and emotion, brings people together to experience something they wouldn’t ordinarily in everyday life. I’ve seen images of people walking around the space, sitting in the space in different locations. For The Whole Earth Chanting, I was thinking particularly of a book by Sylvia Baptista on posthuman spiritualities, which comes into the work with Ent-, but I was also thinking about technology as a new religion or belief system, following authors such as Jeanette Winterson, who has a book called 12 Bytes, Sadie Plant in Zeros and Ones, and Kate Crawford’s AtIas of AI. There are a number of books where people have looked at contemporary technologies and made analogies with religion. I wanted to position quantum computing as advancing that sort of discourse as well.

BW: How important is collaboration for you?

LH: I do enjoy collaborating with people, or discussing, even if it’s just chatting to people not only about my work but about their practice. It allows you to see or understand areas of your work from different viewpoints, which is mutually beneficial. In terms of collaboration, I’ve already mentioned that I’ve been working with Nabihah for three years. She’s a musician, she’s on a record label, she presents on BBC Radio 6 Music, and so on, so she is in a different world from me. I am a visual artist and scientist. When we combine our entirely different practices, we come up with something that neither one of us would be able to make independently. We performed recently at the Southbank Centre, a new commission called Cascade that looked at the colonial history of the Thames. I used AI to reimagine sound recordings from the Thames and images related to it to create new futures. Nabihah also has a degree in history, so she was writing and talking about the past. It was a really experimental performance. I really enjoy collaborating. Ent- is my work but to realise the final piece, I worked with a team of developers – James Stringer, Jira Duguid and Gabriel Stones. The direction, the sketches, everything came from me, but it takes a team to realise something so big.

BW: You have mentioned in other interviews and writing that you are interested in dada and surrealism and I wonder if you could say something about that and how that plays out in your work?

LH: Yes. Making noise or using randomness and chants in my work is a strategy I’ve been employing since I started. In previous works, I did a lot of work with artificial intelligence and machine learning. I’m particularly interested in categorisation and moving away from that into the more dreamlike. Dada sound poetry was a huge influence for me. I did some works – Lady Chatterley’s Tinderbot, Britbot, Euro(re)vision – which were all working with chatbots and natural language processing. Rather than trying to copy the existing, I was trying to move away standard narratives around Britishness, and to move into a space where a machine is creating nonsense with multiple voices. I was looking a lot at Hugo Ball and Kurt Schwitters. In Ent-, you can hear layered voices in the work where the English and German languages are layered over each other. The hybrid creatures were formed using randomness from quantum computers. Quantum computers can generate the only true sense of randomness in the universe. The roll of a dice or turn of a roulette table is never 100% random. With quantum, it is genuinely random. The hybrid creatures were formed through a quantum dice I made, a bit like a surrealist collage, their cubomania method, or exquisite corpse. Bosch was an influence for the surrealists too.

BW: Ent- has only just gone on show, but tell me what you have lined up next? What are you working on now?

LH: Ent- is coming to the Arebyte Gallery in London and, because of the nature of the space, we are going to build a black box in the space, but then there will be other works around that, so that’s what I’m working on at the moment. To take the audience on a slightly different journey, I’m going to be more critical about the use of immersive projection. Immersive projections are often deployed by corporate entities to sell products. They are very corporate spaces without any criticality, so I want to interrogate that problematic. I’m doing that through three small additional video pieces. It will position the 360 as a corporate tool used by tech companies to sell quantum computers and ask what that means.

BW: It is serious, but there is humour in there as well.

LH: There is always a bit of playfulness in my work. There are going to be some surprises at the end. I don’t want to say too much about the narrative journey, but the plan is to take audiences on a journey before and after the black box to unpack more of the details about quantum computing and how it might be used to suck us in. I’m excited to develop the work further.

Reference

1. Can the Monster Speak?: A Report to an Academy of Psychoanalysts, by Paul P Prediado, translated by Frank Wynne, London: Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2021, page 46. First published in 2020 as Je suis un monster qui vous parle by Éditions Grasset, Paris.

• Libby Heaney: Ent- is presented by Light Art Space at Schering Stiftung, Berlin, until 1 May 2022. A component part of Ent- is being shown at the ZKM Center for Art and Media, Karlsruhe, as part of BioMedia: The Age of Media with Life-like Behavior, until 28 August 2022. An augmented version of Ent- will travel to the Arebyte Gallery, London, from 27 May to 21 August 2022.