Piano Nobile, London

1 March – 22 May 2019

by JOE LLOYD

One day, when he was nine years old, Leon Kossoff (b1926) found himself alone in the National Gallery in London. Wandering the rooms with relative disinterest, a single painting spoke to him: A Woman Bathing in a Stream (c. 1654), Rembrandt’s intimate depiction of his mistress, Hendrickje Stoffels, executed with a spontaneity and unfinished rawness rare in the painter’s usually rigorous work. “Somehow,” Kossoff recounted much later, “that painting opened up a whole world for me – not a world of painting so much as a way of feeling about life that I hadn’t experienced before.”

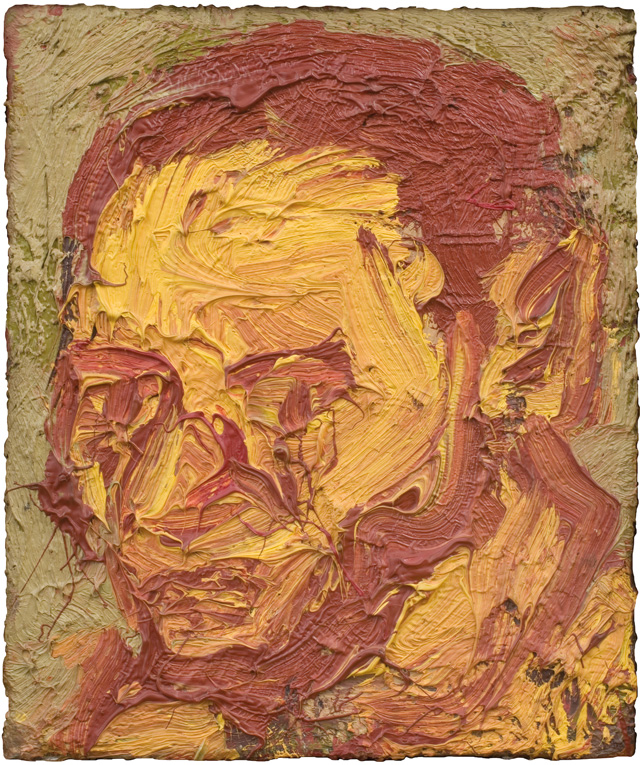

In 1982, almost half a century later, Kossoff returned to the Rembrandt and transposed it into his own, very different mode. Stoffels’ form becomes simplified, her body and surrounds rendered in layer upon layer of oil paint, laid so thick that it appears to wrinkle and peel off the canvas. But the spirit of Rembrandt – in his psychological penetration of his subjects, his earth pigments, his mastery of the reflective qualities of impasto, and the more amorphous sense of cultivating a “feeling about life” – informs much of the later painter’s practice, a practice that covers vast sensorial territory while remaining grounded in the inexhaustible subject that is London.

[image5]

Raised in the East End, one of seven siblings of a family of Jewish bakers, Kossoff is the quintessential artist of London’s swallowed-up peripheries: Willesden, Kilburn, Mornington Crescent, Dalston, Bethnal Green, Spitalfields. In them, he singles out tube stations and train lines, schools and swimming pools, often fixating on those aspects of the city to which residents pay little heed. Kossoff’s portrait sitters – often family members and friends, or models who through extensive sittings became friends – are drawn from this same world, to the point that Kossoff seems to subconsciously paint them into crowd scenes. His London is both a teeming metropole and a personal place inhabited by familiar faces.

A London Life, an exhibition staged across the two Holland Park branches of Piano Nobile gallery, feels like something of a capstone on Kossoff’s career (he is now retired). Collecting 33 of his oil paintings and charcoal drawings, A London Life thus offers the most complete opportunity in more than two decades to scrutinise his work. It spans 1954 to 2008 – almost the entire course of his working life – and affirms his place in the pantheon of postwar British painters.

[image2]

The earliest cityscape on display, Railway Bridge, Mornington Crescent (1954), is by some way the gloomiest. Even compared with the early works of Kossoff’s close friend and contemporary Frank Auerbach, it has a raw, rough impasto and a bleak, earthly palette. This was not entirely by choice: as young artists prone to using vast amounts of oil paint on each work, Kossoff and Auerbach were unable to afford the brighter, more expensive colours. Yet it is difficult to imagine a grimmer account of this innocuous urban scene, its details hidden beneath outwardly abstract furrows of paint.

It can take time to come to appreciate this period in Kossoff’s oeuvre. The mucky palette, the sticky glistening of the accrued layers, the way the paint forms into clay-like clumps: these are paintings that grow from an initial repugnance. But there is an undeniable pleasure to be had in watching the glimmering of light over the volatile, unpredictable surface. And there is something exciting in the way Kossoff elevates train tracks, the machinery of the modern city, as a site of such eruptions.

[image4]

By 1961’s City Building Site, Kossoff’s palette has gained jolts of primary colour. The murk of postwar London has begun to lift, with wartime ruins giving way to rebuilding. It involves some straining to be able to perceive the scene, although, gradually, certain features – such as the yellow streaks that mark construction cranes – become apparent. Kossoff’s representation of the building site doesn’t seem to matter anywhere near as much as the way in which he chooses to represent the building site. It is as if time has been stalled, and the site has been arrested in a single moment. Conversely, however, Kossoff’s process of meticulously working on a painting over repeated sessions calls attention to the lengthy span of time required to capture that moment. Each painting becomes the story of its creation, and, in doing so, becoming what David Sylvester, in an essay on the artist, described as “a living thing”.

[image6]

It is this vitality, above all, that makes Kossoff’s work so transfixing. Over time, as Kossoff’s paint grows lighter and his colours brighter, it becomes ever-more profound. A London Life is enriched by several series that show this occurring over time, as he intensely revisits the same subjects. We see his longtime model Fidelma in 1978, sitting nude with her hands clasped and an expression of eager patience, before encountering her again in 1986 with a downward-looking, pensive expression. The thick outlines and fixed pose of the earlier painting give way to more liquid, flowing brushwork in the second, where Kossoff more subtly renders the contours of her form.

[image7]

A trio of works shows a turreted redbrick school in Willesden hulk over passing pedestrians and cars; we are at once caught in a mundane, fleeting moment and staring at a mighty structure that seems to stand for something more lasting. In a 1981 painting, it stands out, lustrous, against a stormy winter sky; in a charcoal and pastel drawing executed the same year, it gleams palely as the clouds appear to lift. By 1984, in a charcoal and chalk depiction, Kossoff has thrust the school back behind a curving road, replete with zooming cars, and it appears somewhat diminished, isolated by the hum of the city. Yet even here it acquires a powerful verticality with its dashes of red and white, veined like griotte marble, and has a presence that seems to place it beyond the humdrum.

[image10]

This lofty, almost mystical vision of the city occurs throughout Kossoff’s mature work, reaching giddy heights in his renditions of Christ Church, Spitalfields (1989), whose Portland stone facade surges towards the sky, barely able to be contained in the canvas. The most recent painting on display, Cherry Tree, and Tube Train (2007-08), shows a tree in Kossoff’s Willesden garden, propped up by two stakes. Its soft greens bring a sense of renewal and tranquillity to his later works, even as tube carriages thrum below. Here, at this late juncture, nature begins to support the city, and the city to support nature. Life courses through this quotidian scene.

In the preface to a 1974 exhibition catalogue, Kossoff wrote: “The strange ever-changing light, the endless streets and the shuddering feel of the sprawling city lingers in my mind like a faintly glimmering memory of a long-forgotten, perhaps never experienced childhood.” A London Life presents an artist constantly capturing this evanescent sensation.