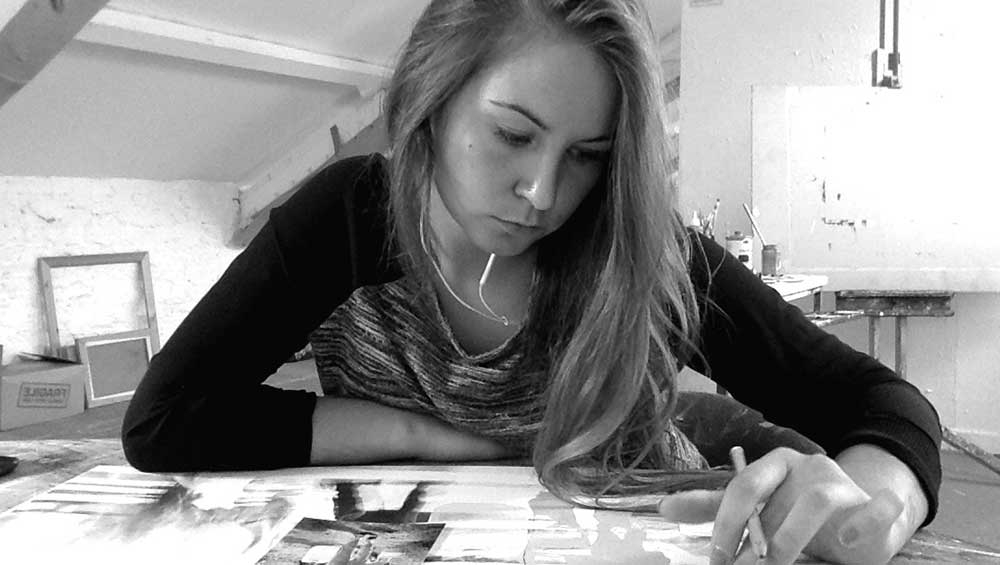

Leanne McDonagh. © the artist.

by JANET McKENZIE

In From the Margins, an EU project designed to give expression to displaced people and refugees, has enabled the voice of Irish Traveller Leanne McDonagh (b1990) to be heard. As one of the six artists in residence at Cork Printmakers in 2022-23, she has created a body of work based on photography and silk-screen printing that celebrates her identity and that of her Traveller community. Rooted in the quotidian activities of her parents, McDonagh, who is one of 10 children, is empowered to document her community from within.

For centuries, Irish Travellers have experienced prejudice from Irish society at large. More than 31,000 Irish Travellers were registered in the 2016 census (the latest census for which figures are available) and many now live in villages and towns, having adapted from their traditional nomadic life. Although they have been an indigenous minority for centuries, it was not until 2017 that they were formally recognised as an ethnic minority by the Irish state. With a shared history, cultural values, language, customs and traditions, they are a self-defined group. Their culture is an oral one that has evolved from a life of freedom from societal convention.

Their culture and way of life has long made them a target of prejudice, leading to marginalisation and poor levels of health and education. On the occasion of the police murder of George Floyd in the US, in 2020, the Irish Traveller movement took the opportunity to address racism towards their community.

Leanne McDonagh. Pavee Presence, 2020. Photograph, 23.4 x 33.1 in. © the artist.

McDonagh is a young artist uniquely placed to represent and record her community from within. She is employed by Munster Technological University as the Traveller education coordinator and is also developing her practice as an artist: she recently illustrated Why the Moon Travels, a collection of Traveller folktales written by a fellow Traveller, Oein DeBhairduin. McDonagh says: “As a member of one of the most socially excluded groups in Irish society, my memories are sometimes spoiled by extensive experiences of being identified as a negative stereotype. However, not all my memories are blemished, and I retain others that are untouched by negativity. I am documenting, both for myself and for the outsider, an artistic auto-ethnographic view of the community before it is lost for ever.”

Studio International visited Cork Printmakers to talk to McDonagh in November 2022.

Janet McKenzie: Your position as a college-educated artist from the Traveller community is an exceptional one. Was it unusual in your family and your community to complete school and then tertiary education, becoming a teacher too?

Leanne McDonagh: Unusual at the time, yes. But this was because there was a strong belief among the community that not many outside the community would hire you, regardless of how well educated you were. This was something that I truly believed until I was about 17 or 18 years of age. Thankfully, I no longer think in this way but, unfortunately, there are others who still do.

JMcK: Where do you live and where did you grow up?

LMcD: I’m currently living in County Cork. I live in a nice little village called Ballynoe, which is between two bigger towns, Fermoy and Midleton. Before I lived in Cork, I lived in Dungarvan, County Waterford. But I was originally born in Limerick, so we’ve moved around a little bit.

Leanne McDonagh. Kith & Kin, 2020. Photograph, 25 x 35 in. © the artist.

JMcK: What drew you to In From the Margins?

LMcD: I was halfway through maternity leave when I first saw it advertised. I have three young boys and normally when I’m on maternity leave, I create some space within that period to do something creative for myself. Being a mother is a privilege and it has influenced a lot of what I do. Hence, when I saw this project advertised, I realised it could be a great opportunity for me, not only to produce some new work, but to also make some new connections with likeminded people. Participating in the residency during my maternity leave allowed me to take a moment for myself and to create some space for my practice.

JMcK: Do you have family to help with childcare?

LMcD: My husband is quite good, and his parents live close by. And my own extended family live within a 15-minute drive. County Cork is very small, even if it is technically the biggest county in Ireland.

JMcK: Have you done printmaking before?

LMcD: Yes, I graduated in fine art from Crawford College of Art and Design in Cork City in 2012 and the course there included printmaking. I really enjoyed the various processes that printmaking had to offer, but I had a tendency break the rules and mix things up. I liked to play around with the different methods and experiment with them. I also tended to use several processes in one piece, piecing an image together, layer by layer.

Leanne McDonagh. Lead Rope 2014. Photograph, 23.4 x 33.1 in. © the artist.

The residency at Cork Printmakers has been a great opportunity to get back in the print studio. I spent the first couple of weeks experimenting in the same way I would have done previously before deciding I wanted to take a more calculated approach. Prior to the residency, I had been working on some new ideas for my next body of work. My work has always been about who I am, where I came from, and what it means to be an Irish Traveller.

JMcK: What does that mean?

LMcD: I am an Irish Traveller, which means I am part of Ireland’s only indigenous ethnic minority, and my work addresses this Traveller heritage. It took me a while to own it because when I was about 16, I was very aware of the tension and differences between the two communities here in Ireland. I was conscious that my community were perceived as different and in a negative light. When I became a teacher, I began to realise that although I had a positive experience of school myself, lots of other Traveller children did not. In the early days of my teaching career, few people were aware of my background so, I was able to subtly observe and overhear exactly what other non-Traveller teachers thought of their Traveller students in the many schools I worked in.

JMcK: Was it very negative?

LMcD: Yes, it was and as time went on, I thought: “You know what, this is not OK.” And I began telling people who I was, and I began challenging their stereotypes. Later, I encouraged the kids to create art around who they were, about their individual identities and their hopes and ambitions for the future. My own work also seeks to highlight that my Traveller community cannot be stereotyped. Often based in photography, I create images that are visually hazy, abstract and elusive, where the viewer has to ask questions about what is actually happening in the image. My work explores the status and intrigue around my community, creating statements and comments that aim to intrigue the viewer so that they might question any stereotypes or preconceived notions they might hold about the community.

Leanne McDonagh. Like-minded Lacks, 2020. Photograph, 25 x 35 in. © the artist.

As a child, I went to some of the local horse fairs. This was one of our traditions and it is something I remember fondly. I remember going to horse fairs and being asked to be photographed by various people. Then, at a certain age, I started to question the motives behind the practice: Where is this photograph going? What do you intend to do with it? What happens after the image has been taken? I stopped allowing myself to be photographed because I felt the outsider’s perspective was not doing justice to the community.

I came to this realisation during my time at college, when I began researching my community and found that most material discovered was from an outsider’s perspective. Many of the articles and images I found were skewed to present a certain narrative. To be honest, I was alarmed by a lot of the material I came across.

JMcK: Where did you carry out your research?

LMcD: Most of the contemporary and current articles or images were found online and these were the ones that really made me think about the outsider’s perspective. They were full of modern-day biases in comparison, perhaps, to the much earlier work of Jack B Yeats, Louis Le Brocquy and Nano Reid, artists who were influenced by our way of life, intrigued by the mystery and romantic notions of the Travellers’ travels, customs and traditions.

I remember finding an article with imagery from one of the horse fairs I used to attend and one at which I had been photographed previously. I found one image with a number of people in it, people I knew personally: this photograph was connected to an article that was very negative, and false. I brought this to the attention of the people in it and, of course, they, too, were shocked about how they were portrayed in the same article and had not realised when standing for the photograph that it would be used in such a way.

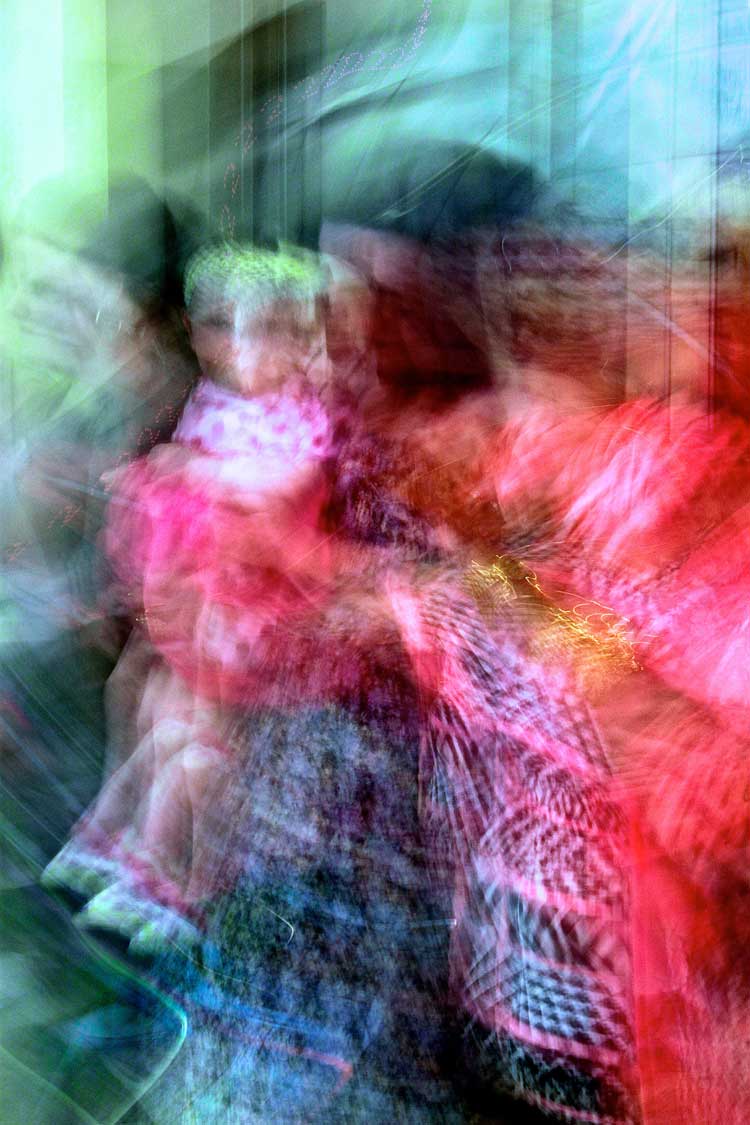

Leanne McDonagh. Nature & Nurture, 2020. Photograph, 25 x 35 in. © the artist.

JMcK: That sounds quite sinister?

LMcD: Essentially, these so-called journalists, reporters, photographers – whoever they considered themselves to be – were collecting information and using it against us. The article was very presumptuous in relation to the image. It was an outsider’s interpretation of my community that presented the Traveller community as a whole in a negative light compared with the rest of the world. That was not OK with me. So, when I went back to that fair to take my own photographs, I decided to capture imagery in a way that had not been done before. I wanted to reject those stereotypes that had been created by outsiders and I wanted to ensure that I did so objectively. I have continued to work in this way now for a number of years, and I really like working with the photographs that I take. I still get so much out of them. The colour, the movement and the motion mean so much to me, and it all relates back to the idea of a bright, colourful and nomadic community.

Many of my artworks are made up of several layers and different processes. I see this in tandem to people and to life experiences. For example, when you meet somebody and you question them about who they are and what they are about, you are literally peeling away layers of their persona, in order to figure out who they truly are. This is similar to what I aim to achieve in my work. I want to show the viewer that, in order to get to know us, you need to work away at each of the layers, discovering our commonalities as well as differences. It is important to me to capture the traditions within the community that I feel are genuine and authentic, but also to capture the everyday, the normal and the mundane. And I also want to show that these people are just like you, the viewer, and as humans we are all ultimately the same.

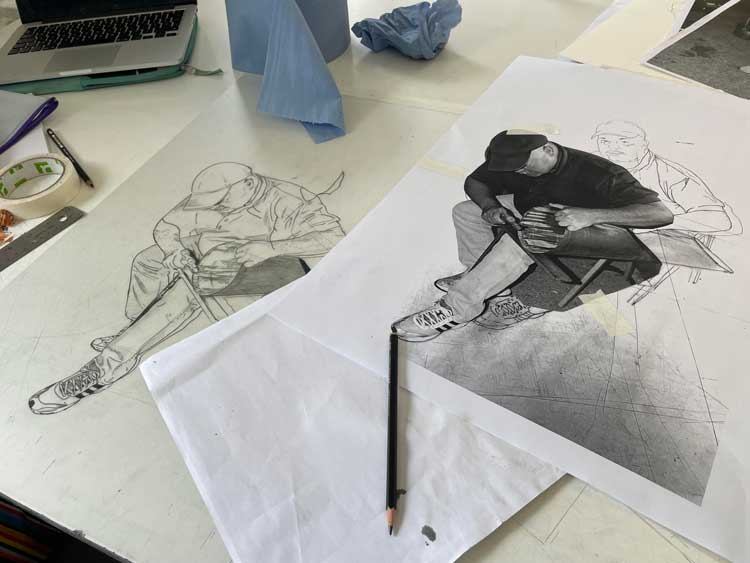

Leanne McDonagh. Work in progress (a), 2022. © the artist.

During this residency I’ve created four pieces, two of which feature my mother and two my father. I really enjoyed creating these pieces as I decided to portray the subjects in a more representational manner than I would have previously.

JMcK: This is a silkscreen print based on more than one photograph?

LMcD: Yes, this piece is titled Tinkering with Tradition. This is my father: his father before him was a tinsmith by trade. In years long passed, tinsmithing would have been one of the more traditional crafts for males within the community. However, with the introduction of plastic to the market in the 1950s, the need for tinsmithing quickly become obsolete.

Traditionally, the father would have passed these skills on to each of his sons, and the son would have continued to hold that role within the community. My father’s father died at the age of 40, leaving behind my grandmother and 16 kids. So, my father never got the opportunity to learn the skill, but a number of years later, he sought out somebody else to teach him. I just thought that this was a lovely gesture in respect of his father, and I wanted to capture that. Tinkering with Tradition, alludes to the fact that the life and ways of many a Traveller has changed but, like my father, we are all still very connected to the past. Tinsmiths would have been known through Ireland as tinkers.

Leanne McDonagh. Work in progress (b), 2022. © the artist.

The Traveller community in Ireland is quite small. According to the census, it was about 31,000 people for 2016 (figures from 2022 census won’t be available until April) However, I imagine it’s much higher because some people don’t want to identify as Travellers and choose to hide their identities for the sake of a more peaceful life. It is also important to mention that the actual act of travelling or being nomadic in Ireland is effectively illegal. Ever since the 1963 Commission on Itinerancy, each and every Irish government has subtly created laws and policies that reinforce their campaign of assimilation. In 2017, however, they did acknowledge our ethnicity, due to pressure from the EU, but many Travellers feel that this was symbolic and that it has not incited any real change to date.

Leanne McDonagh. Horse & Harness, 2014. Photograph, 23.4 x 33.1 in. © the artist.

JMcK: Your father keeps horses?

LMcD: Yes, he always has. There are many issues around keeping horses and animals in the community, because, unfortunately, some people don’t treat their animals as they should. But there are also many other people from other communities who do not treat their animals very well either. There’s a tradition of sulky racing and it happens to be completely illegal. It normally takes place at four or five o’clock in the morning, when there should not be any traffic on the road. I suppose the reason for that is because there is no other facility where this tradition can be accommodated for safely. This always makes the local and sometimes national news, because, unfortunately, every so often, somebody will get hurt or there will be a crash. And, of course, that’s not OK. But then every Traveller in the country will be criticised for that act of one or a few.

-(triptych).jpg)

Leanne McDonagh. Pride & Joy, 2014. Triptych (a), mixed media, 5 x 7 in. © the artist.

JMcK: It’s racist.

L.McD: Pride & Joy is a piece I dedicated to my father and his horses, as he once said to me that his horses are his pride and joy. He said: “Most of my children don’t do what I tell them to do, but my horses will do exactly what I tell them to do.” To which I responded, “They must be your pride and joy”, and he agreed.

JMcK: The ephemeral nature of this work creates a sense of the aura of a person.

LMcD: Yes, and I really like that idea. It suggests that, if you give somebody time, and if you really get to know a person, you will begin to see the truth, you will see the real person and the essence of who they are.

JMcK: Your work has a dual nature, as well as capturing the essential humanity and love in parenthood, you are creating images that question the negative stereotypes towards the Traveller community and way of life. In From the Margins has focused on the effects of negative stereotypes on outsider groups such as migrants and refugees and the importance of being open minded.

LMcD: Yes, I agree, and I would have to say that I am all for open-mindedness and the idea of live and let live.

• An exhibition of work from artists working with In From the Margins will take place at Edinburgh Printmakers; Uprooted Visions, 2 April – 2 July 2023.