Royal Academy of Arts, London

2 September 2019 – 2 February 2020

by ANNA McNAY

Despite popular belief, Laura Knight (1877-1970) was not, in 1927, the first woman to be elected to the Royal Academy of Arts, London (as an Associate Royal Academician) since the founder members, Angelica Kauffman and Mary Moser (selected, however, by the King, not elected by fellow members). Five years previously, Annie Swynnerton had received the same honour at the age of 78. Nevertheless, Knight’s election was something of a coup. It went on to take a further nine years for her to become a full member, and 30 more on top of that before she was invited to the institution’s annual dinner. Such were some of the myriad obstacles in the way of female artists at the time – but more on that to come!

Knight (at this stage still Laura Johnson) began submitting (always rather large) paintings to the Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition in 1895, but was not successful until 1903, the year that she and Harold Knight married. They had met at Nottingham School of Art, where she had enrolled at the age of just 13, having been encouraged by her mother to become an artist. A portrait he painted of her a year later, in 1891, is included in this one-room exhibition, showing her in profile. Knight recalled how it was during the sittings for this painting that she “first got a hint that I meant as much to him as him to me”.

[image3]

Luckily for her career, Knight was a self-acknowledged extrovert, who promoted her work wherever and however she could. She featured, for example, in a British Pathé newsreel, sketching and painting models in a mock studio, and she further published two autobiographies: Oil Paint and Grease Paint (in February 1936, the month she was elected to full membership of the RA, and which became an immediate bestseller) and The Magic of a Line (in 1965, the year of her retrospective exhibition at the Royal Academy – the institution’s first one-woman show). Certainly, she exhibited widely, initially together with her husband Harold, and she also showed work at the Royal Society of Painters in Watercolour, the Women’s International Art Club, the Venice Biennale (1914 and 1924), and with the Society of Women Artists, of which she became president in 1932. As early as 1929, she was made a Dame of the British Empire in recognition of her services to art.

[image4]

On her death, Knight bequeathed a number of items to the Royal Academy, including the portrait by her husband. She had, of course, already donated her diploma work, Dawn (1933). In 1972, a couple of years after her death, the executors of her will also passed on 26 sketchbooks, 290 loose drawings and nine canvases, ranging from c1916 to c1960, and it is from these that this charming display is drawn. The curatorial aim is “to give an overview of Knight’s practice and key themes”: the countryside, the nude and scenes from the theatre, ballet and circus. This is certainly achieved, despite the small scale of the exhibition. There are 20 works on the walls, of which just six are paintings – one the portrait by Harold, but four vitrines contain myriad further sketches and sketchbooks.

The first wall of the gallery focuses on the theme of the countryside, with, among others, the delightful sketch Barbary Lambs (c1936), which captures Knight’s exuberance, when she said of the young animals: “I simply adore them and cannot take my eyes off them.” Seeding Potatoes (1940s), on the contrary, shows the side of country living associated with hard labour, with a simple outline sketch capturing the weight of the heavy buckets the women depicted are lugging.

[image5]

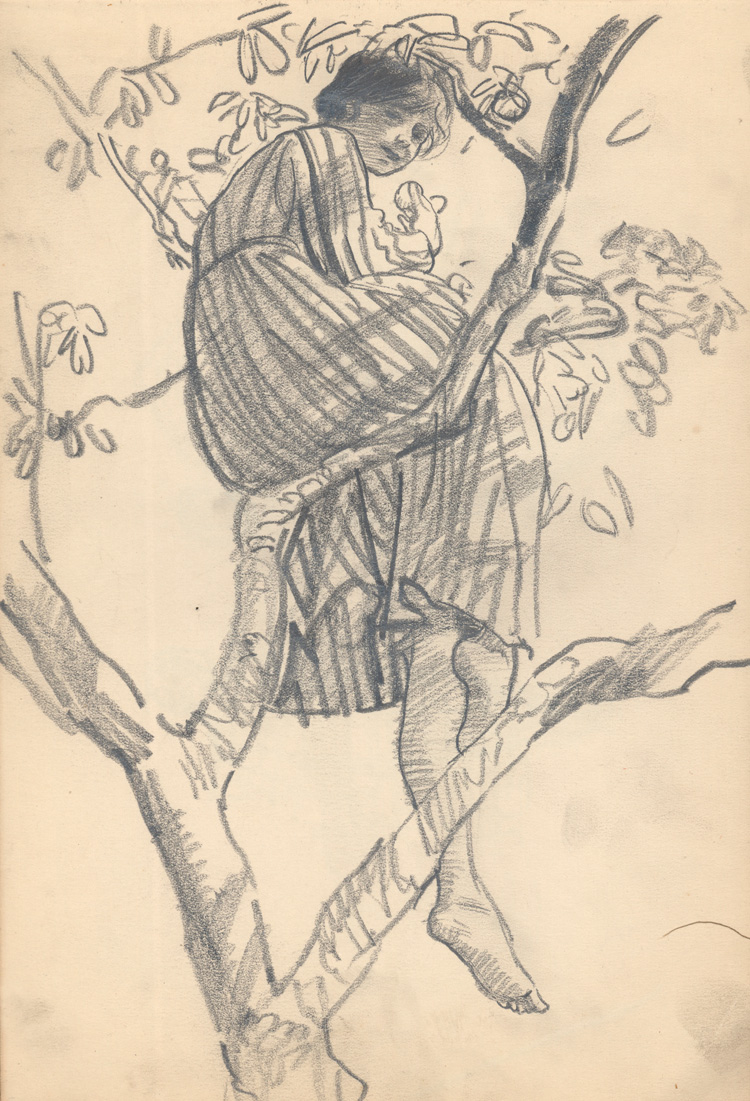

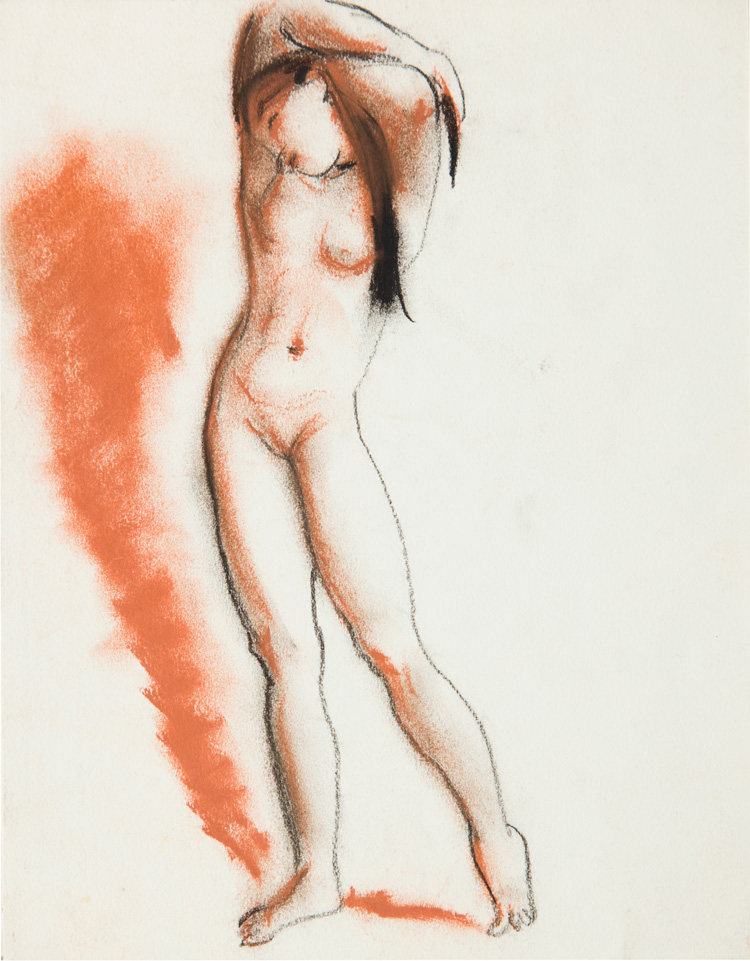

From 1899, Knight moved to Staithes, a fishing village in North Yorkshire, where she joined a colony of artists and, she said, “found herself”. From there, she moved south to the Cornish artists’ colony at Newlyn. The move to Cornwall brought about a noticeable lightening of her palette. After the first world war, the Knights moved to London, but kept a studio in the Cornish village of Lamorna. It was during her time in Cornwall that Knight first became determined to right another wrong inflicted on her as a female artist of the time. As a student, she had not been allowed into the life class on grounds of moral propriety, instead having to paint head and drapery studies, which she abhorred. On arrival in Cornwall, Knight spent hours studying swimmers and sunbathers on the beach. She simultaneously began to hire her own models – often dancers – to paint nude, including her friend and fellow artist Ella Naper, who modelled for the famous and groundbreaking Self-Portrait (The Model) (1913) (not included in this display), which shows Knight at work in her studio painting a nude Naper. The delightful pencil sketch Ella Naper in the Apple Orchard at Trewoofe (c1916) is, however, on display, and captures the simple form of a woman sitting in a tree eating an apple. The smile on her face as she looks down speaks volumes about the two women’s friendship.

[image2]

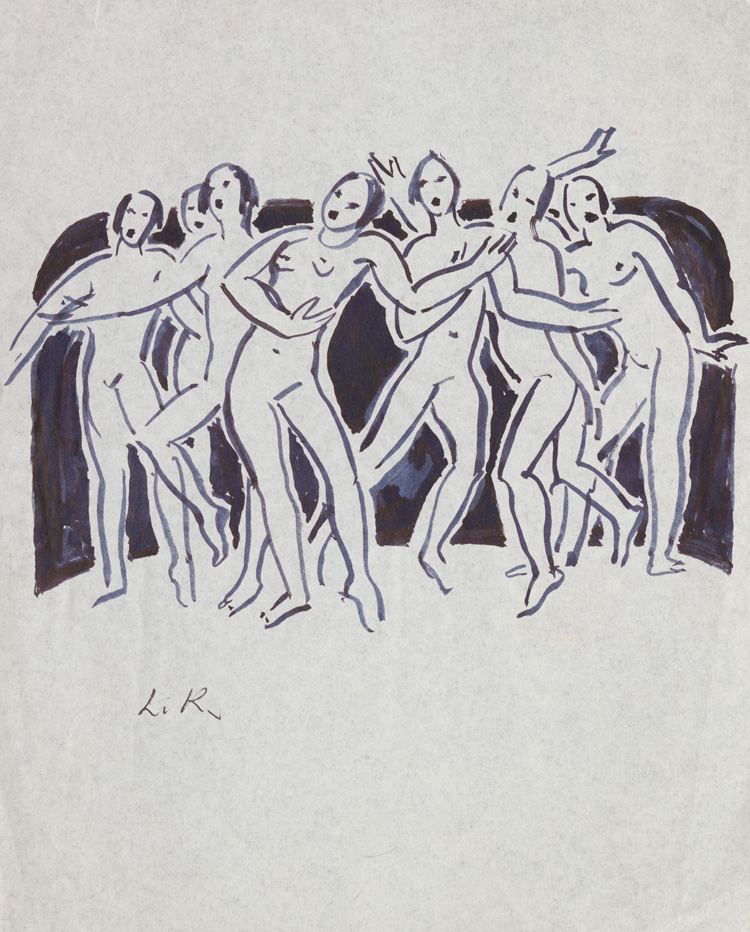

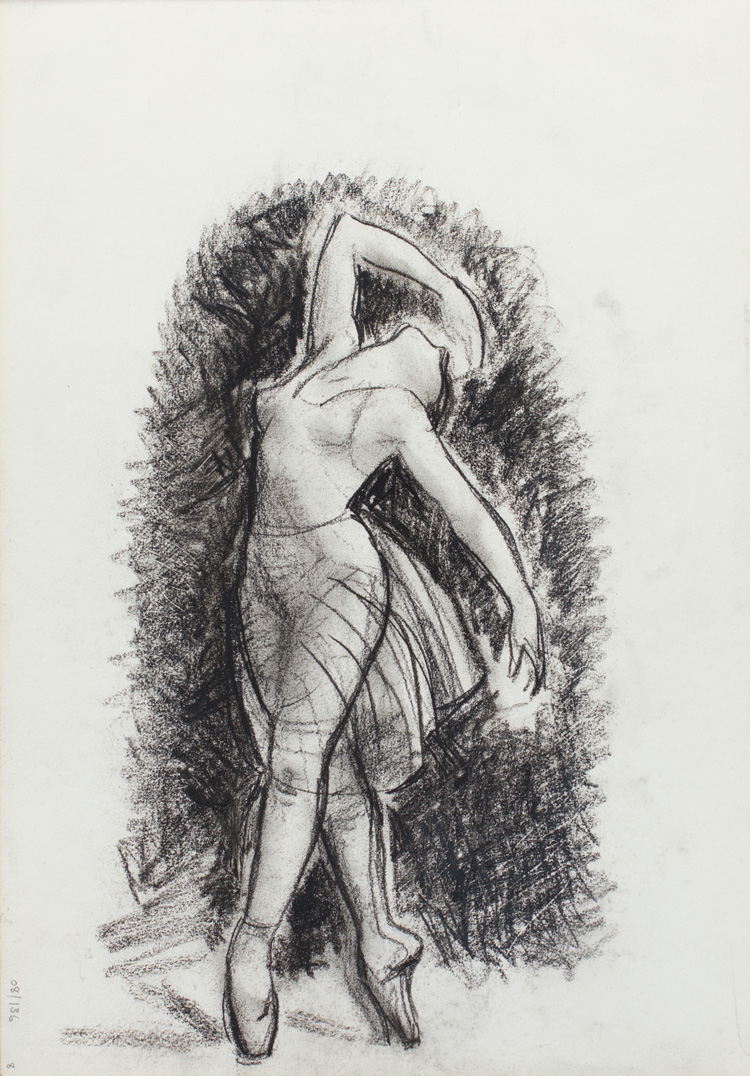

From hereon in, Knight made the human figure – commonly in motion – the main focus of her work. Despite her efforts to study the nude, the majority of her paintings continued to feature clothed figures. (Dawn is an exception, perhaps deliberately so as her diploma work, showing two bare-chested women, in a deliberate riposte to the establishment.) Knight’s interest in dance took hold during the 1910s when Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes were in London. She was later permitted to sketch dancers backstage and to draw the dance classes of the likes of prima ballerina Anna Pavlova. Knight commented: “I knew her every step and gesture in every dance she did.”1 She further spoke of how the eye and pencil needed to “be as one” to capture movement. Her later sketches of the Bolshoi Ballet (c1956) are, again, rapid, in pen and ink, almost traced outlines, overlapping, and, as such, showing movement in an almost Muybridgian photographic manner.

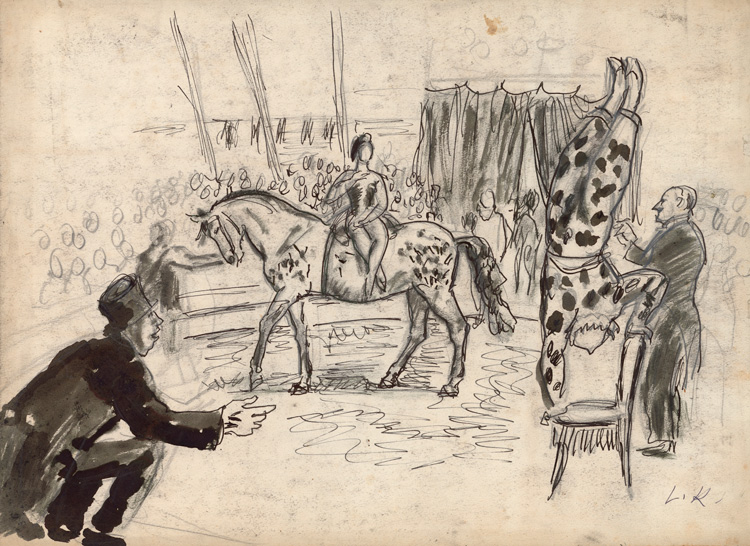

Knight’s earlier experimentations with sketching movement led to series of works of circus performers, touring with Bertram Mills and the Great Carmo; and, following a commission, in 1916, from the Canadian War Records Office to paint soldiers at Witley Camp in Surrey, she began a series of soldiers boxing, several of which are also included in this display. Some of the works are sparse – sketched quickly to capture a fleeting moment; others are more laboured with lots of crosshatching to create a sense of sculptural weight. Often, such detail would be added after the event, from memory.

[image6]

In 1944, Knight received a commission to paint a performance at the Blackpool Ice Drome, opened in 1937 as the first purpose-built ice-skating rink in the world, really pushing her ability to capture speed of movement. Sketches for this are also on display, in particular Study for ‘The Arabesque on Skates’ (c1950), depicting Norwegian skater Sonja Henie amidst an insanity of crisscrosses, suggesting fleetingness, ephemerality, transition and speed – as Knight herself termed her method of sketching: a “lightning shorthand”. Certainly, this selection of sketches demonstrates Knight’s masterful capturing of the details of bodily weight and motion in hasty lines. As she wrote in her autobiography: “Perfection of balance and line became my ideal also, and I revelled in the joy of line for its own sake; the infinite possibilities of composition as exemplified by the human body in movement filled my mind.”2

In her final years, Knight settled in the Malvern Hills, where she died in 1970, aged 92. The final oil painting in the display is of a swimming pool at the bottom of the garden at Colwall Park Hotel, where the Knights used to live when first visiting Malvern. Although the figures of the bathers drying themselves and getting ready to dive recall the backstage theatre and dance studies, the focus here is very much on the water and the reflection of the tall tree, with ripples spreading out from a figure laying with her hand trailing in the pool.

Another of the paintings included is Portrait of Joan Rhodes (1955), depicting a well-known strong woman, billed as “The Mighty Mannequin” and “The Strong Lady of Variety”. Knight paints Rhodes, a woman capable of bending steel bars and ripping up telephone directories, dressed like a society lady, bare shoulders, hair scraped back, carefully made up and with hooped earrings. As such, she captures her physical strength, but also her femininity. Never does Knight paint a passive, objectified woman.

The paintings, nevertheless, are definitely not the highlights of this display. It is the sketches that demonstrate Knight’s skill of observation, her “lightning shorthand” and memory, and her ability to capture life as it passed by. This small but delicious display offers a fascinating insight into the practice of a highly significant figure in the history of the Royal Academy itself and British art history.

References

1. Oil Paint and Grease Paint, by Laura Knight, 1936, page 181, cited in Laura Knight: A Working Life, edited by Helen Valentine and Annette Wickham, published by Royal Academy Publications, 2019, page 71.

2. Ibid, page 19.