by VERONICA SIMPSON

Laura Buckley (b1977, Ireland) came to art through a love of pop music, poring over music videos in her Galway bedroom as a teenager in the 90s, she internalised the combined power of sound and image. Having studied painting and sculpture at the National College of Art and Design in Dublin, she waited six years before taking up a master’s at Chelsea College of Art and Design in London; she says she needed to be “hungry” enough to want to reach the next level.

Hungry she may have been, but she was also determined, with a 10-month-old daughter to care for by the time she enrolled for her MA. That sense of purpose and commitment, as well as the expansion of perception that motherhood brought, has been pivotal in her work since then, as has the decision to buy a video camera to record her daughter’s early years. Thus film and sound found their way into her sculptures. Combined with light and structure, these elements are layered to create immersive environments that summon up moments of humdrum, daily experience only to disrupt them via mirror and light fragmentations and a mixture of unearthly, everyday and distorted noise.

[image2]

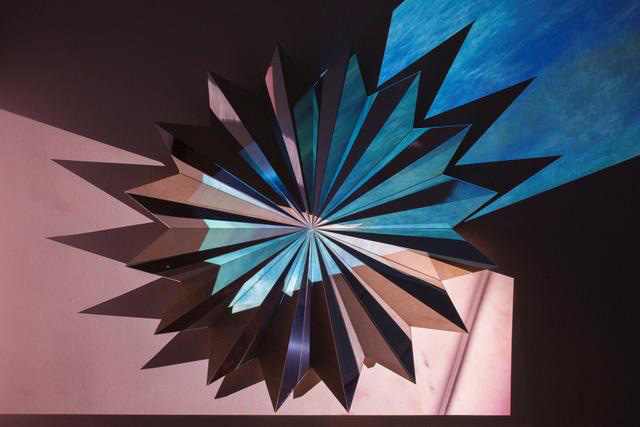

Buckley’s Fata Morgana sculpture, first devised for Cell Project Space, London, in 2012, has been reassembled and expanded to form the centrepiece of the current Kaleidoscope exhibition at the Saatchi Gallery in London. At its first showing, the Guardian critic Skye Sherwin was moved to write: “Her fusions of sounds, images and objects seem to turn our thoughts inside out.”

Her MA show was bought up by the Zabludowicz Collection, which represents her. Recent solo exhibitions include: The Magic Know-How at the Site Gallery, Sheffield (2013); The Mean Reds at Supplement, London (2011); and Waterlilies at Mother’s Tankstation in Dublin (2010). She has also taken part in many group shows, mainly around Europe, and features in several important collections.

Veronica Simpson: I was intrigued by a description of your early years, growing up in a small town in Galway, attending a convent school. Aside from the obvious exposure to religious imagery, what exposure did you have to art as a child that made you think you wanted to become an artist?

Laura Buckley: I wasn’t used to visiting galleries, so my kind of interest in art was very much pop culture, such as the very early guitar bands, early electronic music and that visual imagery of music video, which I work with now, but very escapist. It was very much about coming back from school and getting into my room and recording songs from the radio, then playing them back. But I really enjoyed the intimacy of making imagery and making something meaningful and connecting. Through sound and vision, you can connect with the viewer on different levels.

[image3]

VS: It sounds as if you were more drawn to music at that point?

LB: Music, I loved, yes. I studied piano for many years and ballet, too, and was very into science and English. I loved to write. And now all of these things have fed back into my work, which is fantastic. My first films were silent. I didn’t intend to start making moving imagery until I became a mother and got a video camera for that reason. I was coming from painting and sculpture and installation and really breaking down the function of art and representation. And so the first films are silent because, as I say, my background doesn’t come from film. The sound gradually started coming in and now I collaborate a lot with musicians I’m interested in and I also make my own music. I’ve done a couple of music videos for Plaid and New Young Pony Club. I enjoy the collaborative process because I do everything myself, really, apart from the fabrication … Otherwise, the filming and editing I do on my own and it can become quite isolating.

VS: How do you start compiling the images and sounds that eventually go to make up a piece? How do you shape these fragments as you go along?

LB: You just never really switch it off. That’s what happens. When I’m working on a show, I’ll start collecting clips and start playing with them. Generally, the installations are in movements or acts, and they’ll be focused on one or two psychological states. It often reflects where I am in my life. Some works are quite celebratory. An installation called Waterlilies, in 2010, for my first solo show, at Mother’s Tankstation in Dublin, was very melancholy. My second daughter was still a baby, and there are some very domestic sounds; then, I’m pushing it through this process that completely expands it to this heightened everyday reality, and abstracting reality, but just allowing … the freedom to see things in different ways.

[image10]

I go about collecting clips to a certain point and they’ll be in groups that will be acts, and that’s how they come together. Some of them are quite long shots, real shots. And a lot of the more abstract footage is … I work a lot with digital print, which I’m not known for, but I want to get them out into the world a lot more. I make digital prints using my scanner, and then I set up a tripod on my desktop and on my big desktop computer I film the scans; I navigate in and out of the scans. This forms the abstract content of the footage. Some of these can be objects or people that can be in the films – such as a finger or hair, or a meaningful object that’s close to me emotionally, or aesthetically.

VS: What sort of technology do you use to help with this process?

LB: I’m really basic. I just have folders of information. I see it as a palette as well. You have a palette of sounds and then you can start to make the audio collage or layer them. But I really like repeating sounds, taking ambient sounds and making beats with that sound. For example, my older daughter was filming my younger daughter, who was dancing on bubble wrap, making these popping sounds. I took a clip of a little bit of that sound. I make repetitive beats by using everyday sounds like that. I like a lot of droning sounds as well, synthesised tones with the human voice, and with ambient sounds of the home or the park, or wherever it may be.

[image9]

VS: In reviewing your work, there is often mention of how disorienting it is. Is that a quality you deliberately try to create?

LB: Yes, I guess there is a psychedelic, escapist element, taking mundane things and making it extra mundane. You can still see the mundane thing in its original capacity, if you view it from the other side of the structure. With Fata Morgana, you can still see it as a straight film on the back (the film is projected undistorted on to the rear of the hexagonal structure), or you can choose to go into it, lie down in it, play in it. Children connect really well with it. It’s a very shared experience. For me, when you go to an exhibition, who you are in the space with is a really personal thing. It is like an event for me, when I go to a show that I really get into: I enjoy watching the other people in the work as much as the work itself.

VS: You have said in the past that your installation work really took off when you saw Anthony McCall’s show at the Serpentine Gallery in London in 2007, and how he went beyond meaning to create an experience for the visitor. But although you provide this spectacle, you are still very much concerned with meaning.

LB: Yes, that’s the idea.

VS: We seem to be at a moment where the power of Instagram is such that often, when you go to a gallery you can see the work that they have decided will become the “Instagram moment”. Your work lends itself to that – it is immediately appealing and photogenic. Could you see yourself getting to a point where Instagrammers are forced to queue for hours outside your work – as with Yayoi Kusama’s shows – in order to grab that iconic Instagram post?

LB: No. It’s a zeitgeist that has to pass. It has to die down. It is a dumbing down. It’s just instant gratification.

VS: But you have to allow that, with a piece as appealing as Fata Morgana, there is that danger.

LB: I struggle with that, with a lot of my exhibitions, when they’re reviewed. The content of the film is very integral to the whole work and the message, but often that doesn’t seem to get picked up as much. Even when I might be expressing something quite strong. Attract/Repel (shown at Eigen + Art Lab, Berlin, in 2016) was a work that was angry. It came from a hard time in my life, a reaction to this relationship situation. There is a lot of very strong content.

[image11]

VS: It must be frustrating when people don’t pick up on that.

LB: Sometimes. But it’s also about trust. I think a lot about trust, about what you are presenting. With this piece, Fata Morgana, the title means mirage. One of my installations is called Shields. I feel very strongly about trust within the whole concept of art galleries and what you’re giving out and how much you’re keeping back. With the broader media, how do you trust what you’re presented with? Fata Morgana is that idea of a false image, something that’s luring you towards what isn’t true. It’s a dream. That’s why the title really rings true with me. It is such a personal thing.

VS: This work was originally made for a much smaller space. You have a huge room in the Saatchi gallery. That must be exciting, seeing the work anew in a different context.

LB: We extended (the structure): it’s almost twice as long. It’s nice to have lots of space around it and hopefully it won’t feel too busy with lots of people around. At Cell Space (where it was first shown), I did a performance. I shot a video in it, for New Young Pony Club (before the band changed its name to NYPC in 2013). And then I did an event, with Andy Spence from the band. We had to do it in two performances because the space wasn’t big enough to fit all the people who wanted to come. I haven’t discussed it with the Saatchi gallery, but it would be lovely to do a performance in this bigger space. Seeing people’s reaction to it is great. I love that when I’m showing work, the space becomes the work. The work can reach out as big as the space is. I love the power of it in that way.

[image8]

VS: Although it has a sinister side, Fata Morgana seems quite celebratory. You have said that your earlier work was more anxious and melancholy. What emotional state would you say your work is at now?

LB: At the moment, I’m more positive. I went through a big separation two years ago, after 13 years, with two kids. This show is really good timing because I’m just about coming out the other side. During that period I made some quite angry work. The last two shows, Melusine (at the Arthouse Foundation in October 2016) and Attract/Repel, were just when the separation was happening, so they were quite aggressive and sad. But I think I’ve got all that aggression out of me.

This band I worked with, Plaid, are electronic geniuses and I’ve loved them since I was 18 and I gave them this brief of anger and some footage and (they) just came back with this massive, really amazing, piece of sound that’s so fantastic. So, I feel like now, I’m definitely going into a new kind of place. I feel a lot lighter. New collaborations are starting. It’s good to be starting afresh.

• Laura Buckley’s Fata Morgana sculpture and video can be seen as part of the Kaleidoscope exhibition, which is at the Saatchi Gallery, London, until 5 May 2019.

-1.jpg)

-10.jpg)

-2.jpg)

-4.jpg)

-5(1).jpg)

-5.jpg)

-7-(1).jpg)

-9.jpg)