Hammer Museum, Los Angeles

29 September 2019 – 5 January 2020

by MATTHEW RUDMAN

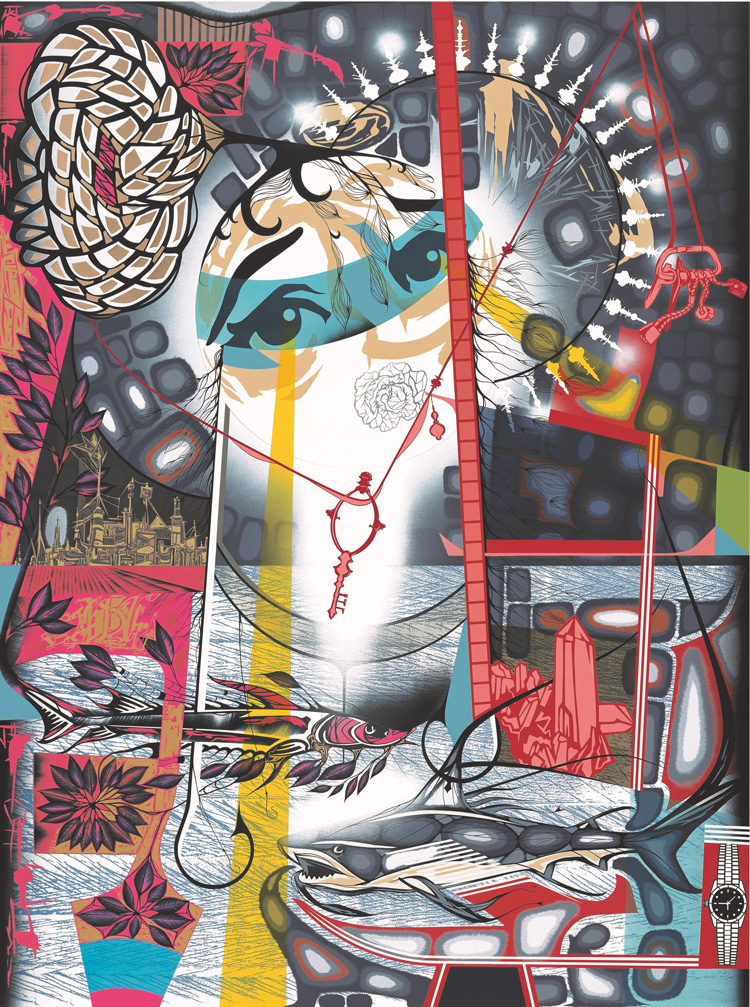

Sex, death, gun violence, consumerism, class and gender identity – Lari Pittman (b1952, Los Angeles) is not shy about tackling the big themes. Declaration of Independence, a major retrospective of the artist’s almost four-decade career, is both astonishing and exhausting. Comprising 80 paintings and 50 works on paper spread out across nearly the entirety of the Hammer Museum’s exhibition space, the exhibition clatters through emotional highs and lows, charting the development of Pittman’s impressive technical skill and singular visual language of marionette pilgrims, magical eggs and aqueous wonderworlds.

The exhibition title sets the tone from the beginning: Pittman’s artwork strikes a defiant tone, blending sharp critique of 1980s and 90s US social and political life with a powerful desire for recognition. Pittman, who is gay and of Colombian-American heritage, uses monumental scale and bombastic, layered imagery to tell compelling narratives of the tension between public and private perceptions, queer identity in the era of the Aids crisis, and the intermingling of written and visual language across different cultures.

[image8]

Pittman spent several years of his childhood living in Colombia, an experience that the artist later drew on in his highly cosmopolitan works, which so often feature patterns, references, visual motifs and languages drawn from cultures around the world, particularly Latin America. Returning to the US, Pittman studied briefly at the University of California, Los Angeles – where he now works as a professor in the department of art – before joining California Institute of the Arts, from which he received his BFA in 1974 and MFA in 1976. There, Miriam Schapiro, who co-founded the university’s feminist art programme with Judy Chicago, became a close mentor to Pittman, even though he was not formally allowed to enrol in the programme.

[image2]

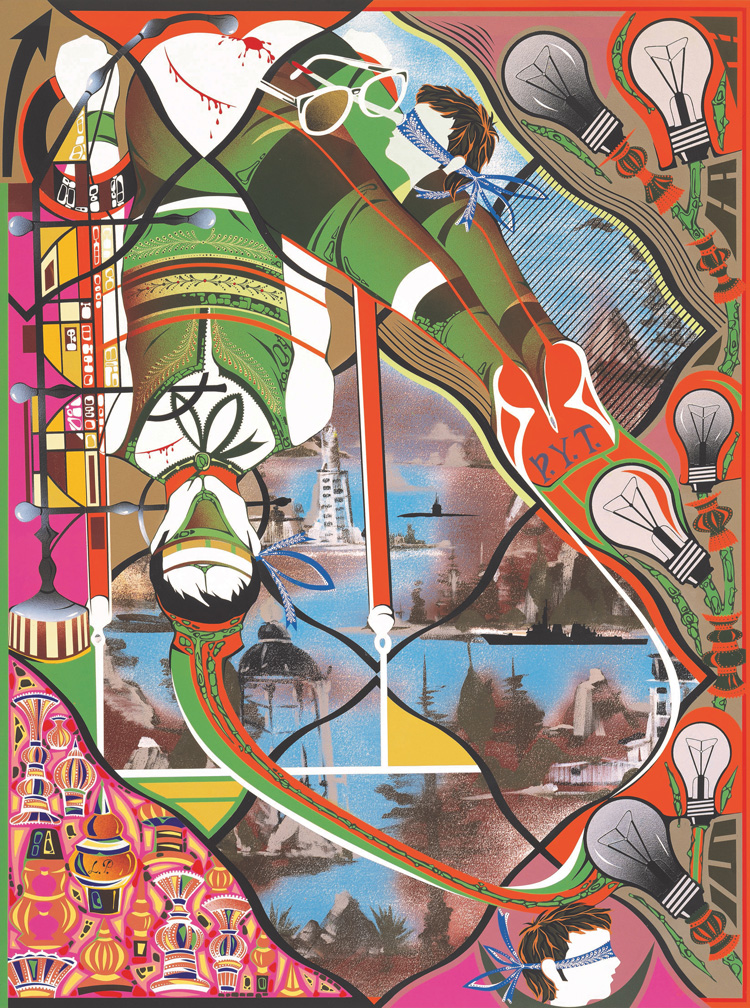

Today, we think of California art in those years as dominated by minimalism, particularly the light and space aesthetic of Larry Bell and Robert Irwin. But the first works on show from this early period of Pittman’s career show that his head was in a very different place. Pittman’s generous canvases are a riotous collage of shape and texture, incorporating wallpaper patterns and found objects into a dense layering effect, with figurative details and landscapes couched within colourful abstract frameworks. These early works show Pittman’s commitment to a distinctive kind of decorative maximalism that would be the hallmark of his later career.

In July 1985, Pittman was shot and critically wounded during an attempted burglary at his home. This rupture, combined with the mounting Aids crisis and the Reagan administration’s lack of action to curb the epidemic, drove Pittman to explore more overtly social and political messages in his work, adopting the visual symbolism of the US for subversive, critical purposes. An American Place (1986) is a standout, a broad canvas dominated by a large, semi-automatic weapon shooting out a bleeding-heart shape, suspended above a black picket fence, inverted from the typical Americana-white. The work’s scale immediately grabs attention: sharp colour blocks are offset against a mustard-coloured background, the spindly components of the gun withered and sickly. Despite the heavy subject matter, the surfaces of Pittman’s paintings are dancing with decorative theatricality: clusters of marbled eggs float incongruously underneath the gun, and withered gourds bloom with bright pink flowers.

[image5]

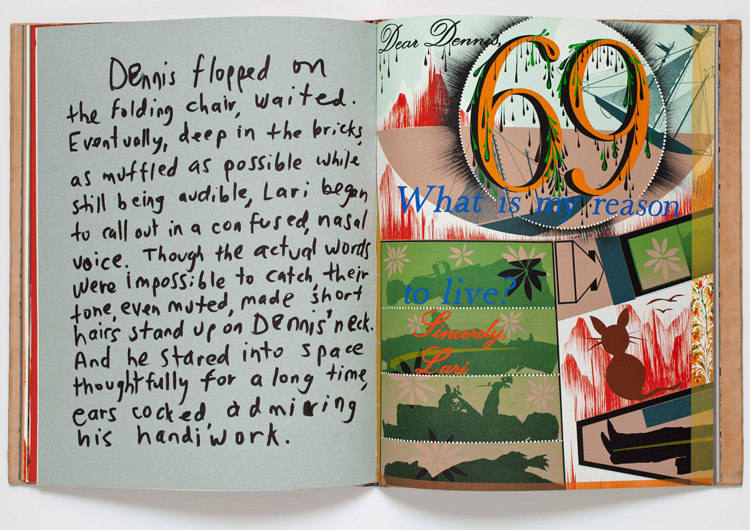

Throughout his career Pittman has produced artworks in sets, series of works closely associated in theme and visual style. As the 80s drew to a close, he began to explore themes of sexuality and gender identity more closely in his Beloved and Despised series (1989-90). Large-scale diptychs feature silhouettes of men and women in Victorian dress enclosed within assorted eggs, orbs, water drops and calligraphic numbers. The imagery is dense, colourful and rewarding to interpret: one painting shows two dandyish men enclosed within parentheses in ornate oval frames, positioned as if they are hiding underneath the crinoline dresses of two Victorian ladies. In another, a suspension bridge for the townsfolk to use emerges from the erect penises of two men, positioning private homosexual relationships as something that can be a positive, generative force for society.

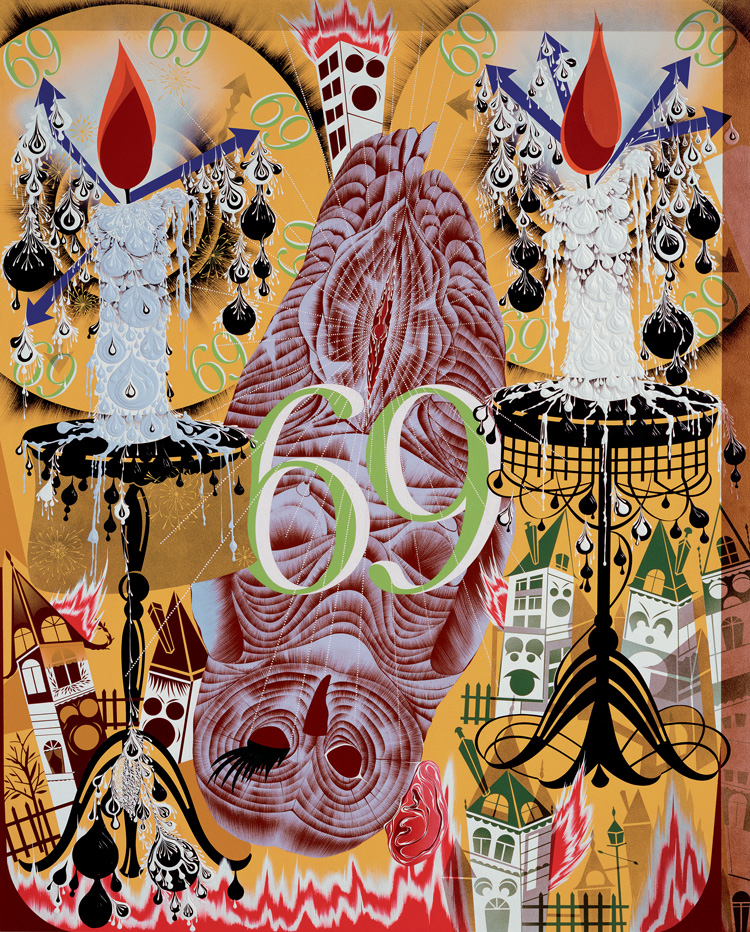

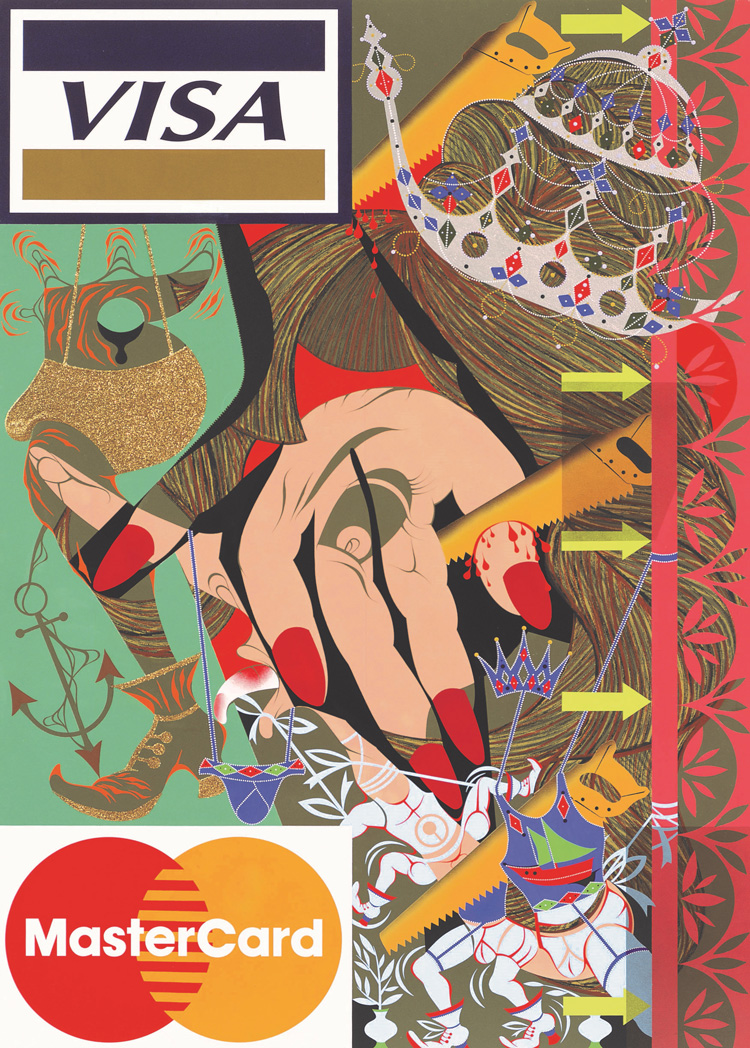

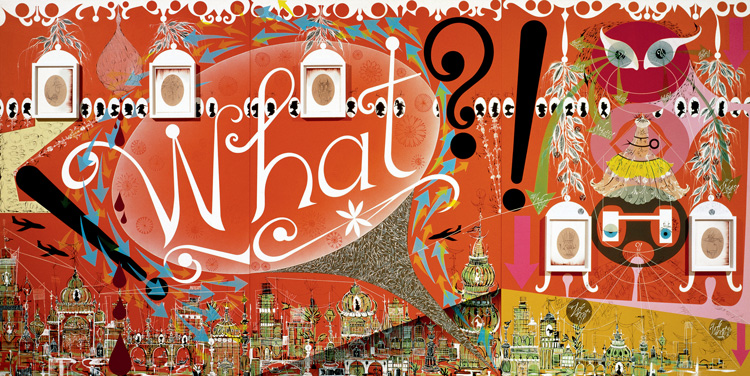

Pittman’s works from the 90s take aim at American consumerism, credit card and pharmaceutical logos adorning noisy, aggressive canvases fit to bursting with pilgrim marionettes and lettering in fairground typeface exhorting us to “CUM N’ GIT IT’ and “GO FOR IT!”. His Needy series (1990-92) is another standout, each canvas featuring a regal, genderqueer owl at its centre, adorned with bejewelled crowns or dripping with candlewax. In these works, Pittman shows off his extraordinary technical virtuosity, using acrylic and enamel paints to intricately layer finely detailed droplets on top of each other into a fractal landscape. It is a visual philosophy of more, more and then some more, and it is often intoxicating to behold.

[image6]

These are not difficult paintings to decode, and that is part of the fun – these are legible artworks, with flying arrows directing the eye this way and that, as if inviting the viewer to read the paintings sequentially like a graphic novel. They resist clear, logical meanings – what does the number 69flying out of an upside-down owl’s oversized vagina really mean anyway? – but there are clear and potent ethical imperatives and messages that cut through the ornamentation and give one pause. In conversation at the Hammer Museum with chief curator Connie Butler, Pittman remarked that he is “not interested in that certain point at which meaning arrives for either me the artist or you the viewer”. In the frenetic collage of these paintings, multiple meanings and avenues of inquiry are available to the viewer. He remarks mischievously: “I like to be utterly useless.” Arrows and numbers fan out in different directions, while the paintings themselves seem to drip and melt under the weight of all those motifs and references.

From the 2000s onwards, Pittman shifts his gaze inwards: gone is the political commentary, and figures all but disappear from view in favour of highly detailed and ornamented interior landscapes. These glossy works are impressive for their vivid, hyper-detailed cartoonish style, dramatic lighting and kinetic flair – Pittman’s technical skill is obvious. However, at this stage the retrospective does buckle somewhat under the sheer number of artworks on show, the narrative thread of the artist’s career as a whole becomes weaker. Nevertheless there are highlights – The Making of a Boy, 1952 (2012) is a strange self-portrait playing with ideas of matrilineal heritage: centred on a perfume bottle bearing Pittman’s birth year, the work features four floating women in native American dress blowing eggs through thin pipes.

[image3]

The Orangery is a fitting refuge for visitors fatigued from the frenetic hyperbole of Pittman’s large-scale canvases. The installation, which takes inspiration from Pittman’s 2010 exhibition Orangerie, at Regen Projects, Los Angeles, draws on the architecture of European orangeries, and is a semi-enclosed space within one of the final rooms showcasing the artist’s extensive drawing and sketching practice. Individual drawings are arranged on a hand-painted trellis like fruit on a vine – the visual metaphor is pleasing, even if the drawings themselves overwhelm in their sheer quantity and range of styles, ideas and cultural touchpoints.

It is hard to come away from this exhibition without admiration for the sheer fecundity of Pittman’s imagination and formidable technical skill. Declaration of Independence is a retrospective bursting with fresh ideas and sometimes downright bizarre characters and historical allusions, and all the better for it. Ultimately, Pittman’s works are fascinating; they are fun and they don’t take themselves too seriously. To put together a retrospective of an artist that takes such pleasure in resisting easy meanings and grand narratives is always difficult, and Declaration of Independence more than hits the mark.

• This exhibition will tour to Kistefos Museet, Jevnaker, Norway, from 24 May to 5 October 2020.

.jpg)