by LILLY WEI

Belgian artist Koen Vanmechelen (b1965, Sint-Truiden) is a conceptual artist with a global profile. For nearly two decades, he has investigated biocultural diversity, collaborating with scientists from a wide range of disciplines. In 2000, he debuted his Cosmopolitan Chicken Project (CCP), an idiosyncratic, innovative multidisciplinary venture that proved to be prescient as more and more cultural practitioners intertwine art and technology. Based on the interbreeding of chicken species across national borders, he sought to produce hybrids of increasing resilience. As a bonus, they also became increasingly spectacular in appearance, particularly their remarkably sumptuous plumage. In 2014, he achieved his longtime goal of a “world-hybrid chicken”, the Mechelse Sulmtaler, an 18th-generation fowl that carries the genes of all the world’s chicken breeds, which he thinks of as a metaphor for the human condition and a framework for the future.

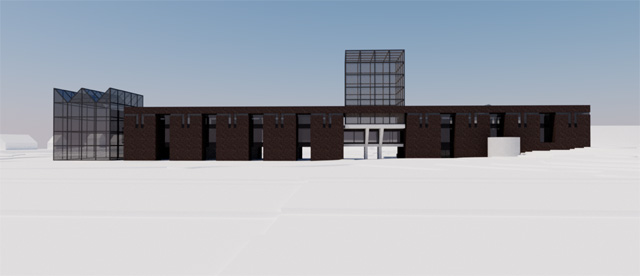

La Biomista (“mixed life”, says the artist) is a consolidation of his enterprise, currently located in Hasselt and Meeuwen-Gruitrode in northeast Belgium. Sited in Genk on the extensive grounds of a former zoo, it officially launched on 9 December 2015 and is scheduled to open to the public in 2018. It will be the new headquarters for Vanmechelen’s Open University of Diversity (with branches in Detroit, Havana and Harare) and includes a grand studio designed by Swiss architect Mario Botta. La Biomista will house his art production and installations, as well as the CCP, its breeding apparatus and its foundations and subprojects. Vanmechelen’s work is currently on view in GLOBALE: Exo-Evolution, curated by Peter Weibel, an exhibition about art and new technologies at the Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie (ZKM) in Karlsruhe, Germany until 28 February, and will install an edition of his CCP in Detroit later this year, as both an art installation at Wasserman Projects and a long-term ecological collaboration with the city. The following is an edited interview with the artist at his studio in Hasselt.

Lilly Wei: Could you tell me about La Biomista, the new park you are creating in Genk, projected to open in 2018?

Koen Vanmechelen: Yes, but let’s jump back a little. Around 20 years ago, I started a crossbreeding project with chickens from around the world. I did this because I discovered that all chickens originated from the red junglefowl or Gallus gallus. Humans brought the junglefowl around the world and bred chickens that represented the culture of their country. For example, France’s poulet de Bresse is red in the head, white in the body with characteristic slate blue legs, the tricolour of the French flag. The Chinese created the Silkie, its feathers silken in feel, and Turkey produced a long crower, suggesting the call of the muezzin.

LW: So, chickens became national emblems?

KVM: I see it as the representation of culture in a living creature, but is this right or wrong? I don’t know.

LW: When did chickens first appear?

KVM: The domesticated chicken goes back 7,000 to 10,000 years. But you have to crossbreed once in a while, otherwise the genes will not be refreshed and there will be a collapse. Crossbreeding is a vital evolutionary force.

LW: So, you started the Open University of Diversity in Hasselt?

KVM: Yes, and I made a lot of artworks that were images and narratives about crossbreeding and diversity, but I also developed research foundations such as the Walking Egg Foundation, named after a sculpture of mine, which deals with fertility in developing countries. Then there is the Cosmopolitan Golem project, which is involved with children’s rights. We go to developing countries and show children that they can express themselves through poetry, stories, dance and visual arts. We teach them a language so that others will listen to them. This is very important. I have gone to 33 countries already; this project inspires so much hope.

LW: Why do you think of it as a golem?

KVM: I made a big wooden geometric sculpture when I was 18. Looking at in my studio, I thought it looked like a golem, a giant. Later, I learned that golem stands for big evolutions.

LW: It does?

KVM: Yes. Einstein talks about the computer as a golem.

LW: So it’s not just a monster from Yiddish folklore, an inanimate clay hulk brought to life?

KVM: It is, but it can also be a saviour. I realised that my Cosmopolitan Chicken Project is also a golem since it provides the world with the community chicken. It’s a chicken with new genetic combinations and greater genetic diversity; it is more fertile, with a stronger immune system. It’s a golem. After 20 years of crossbreeding, the DNA of this chicken has become enormously rich. We have exchanged genome books with Detroit and Harare, [which are] other venues for the CCP, as is Havana. If you give this book to a geneticist, he will know exactly what it means. The 30m genes in one community chicken is obviously much more diverse than the four million in an industrial chicken.

LW: Why does that matter?

KVM: The industrial chicken is not vital. My chicken is vital and adaptable. A community chicken, for instance, can thrive outdoors in an open environment with great temperature shifts. An industrial chicken must be in a barn, not really living at all.

LW: What distinguishes a community chicken from an industrial chicken?

KVM: A community chicken is not uniform; every chicken has its own distinctive identity. An industrial chicken is all brown or all white, but if you crossbreed them with a cosmopolitan chicken, they also become diverse. And you see it with people.

LW: With people, it sounds more complicated, like a eugenics experiment.

KVM: No, not at all. My project is going in the opposite direction. It’s the industrial chicken that becomes the monster because it is bred according to a specific genetic formula.

LW: Aren’t the mechanisms the same?

KVM: No, they are not. The beauty of the project is that it is about freedom. If a chicken from Belgium breeds with one from France, the result is completely free. If you crossbreed their offspring with a chicken from England or America, the result is again completely free. We are not selecting them for the best genetics and we are not inseminating them. We give them freedom in breeding. It is the opposite of trying to create an überchicken. Crossbreeding is expansive while inbreeding narrows. It is about open genetics and you don’t know if the result will be brilliant or not. It is a metaphor for human existence and about freedom.

LW: And La Biomista? It sounds quite ambitious.

KVM: The mayor of Genk, Wim Dries, gave me 25 hectares in the city for my project. It was formerly a zoo and consists of a park and a villa that I have been familiar with from childhood. He is enthusiastic about the Open University of Diversity and the CCP projects that I have been working on in my studio and farm. He believes they would be of enormous benefit to the city. I saw it as a great opportunity to join the Open University and the CCP and its foundations with my studio practice. To me, Biomista means a new world of biodiversity and hybridity.

LW: Would you discuss the organisation of La Biomista, structurally and conceptually?

KVM: La Biomista is divided into three entities: the renovated villa, the new studio and the re-landscaped park. I want to create a conflict zone between culture and nature. The foundations will be in the villa, which is about the human. The conflict between culture and nature will take place in my studio, being built by the great architect Mario Botta. In the front of the park there will be domesticated animals, the llamas, dromedaries and the chickens, and in the back there will be the wildlife, the eagles and the wolves. The visitors will move slowly from domesticated to wild life. This is how we should live; the contrast is essential. We have to give space for wildlife and we have to give space to the humanised, the domesticated. And we meet in the grey zone between.

LW: Is this your Jurassic Park?

KVM: In a way. It’s a park that offers education and knowledge, where we can reflect on society. We have forgotten that we are part of nature. Look at the environmental problems we have created by forgetting that. La Biomista will be more advanced in its research and projects than what we are doing now. Now we are discussing society, the present. At La Biomista, the conversation will be about the future and ways to create a new sustainable, diverse society.

LW: Yet you consider yourself primarily an artist?

KVM: Yes, I do. An artist is always in between things. Even though I am not a politician, not an activist, I would say that all art comments on society, although not all art is critical of it. What I want to find is the moment of change, of mutation. An artist is always finding this kind of mutation, arriving at something that was unknown before. That’s what I think being an artist is.