The Sackler Wing of Galleries

Royal Academy of Arts, London

4 November 2018 – 3 February 2019

by ANNA McNAY

The year 2018 marked the centenary of the deaths of two of Austria’s best-known and best-loved modernist artists – Gustav Klimt (1862-1918) and Egon Schiele (1890-1918). Although Klimt never formally taught Schiele, the younger man was widely thought of as his protégé, and, by the time of Klimt’s death from pneumonia, following a stroke, in February 1918, Schiele was acknowledged as his successor. Tragically, he, too, was to die, eight months later, in the flu pandemic. Although both artists left behind a great number of paintings, the core of each of their practices was drawing, which constituted a fundamental daily activity for them.

Klimt left more than 4,000 drawings – most devoted to women; Schiele, in his short life, created 3,000 drawings and watercolours. The Graphic Art Collection of the Albertina Museum in Vienna, founded in 1776 by Duke Albert of Saxe-Teschen, holds a large number of works on paper by both men, and, for this centennial collaboration with the Royal Academy of Arts – one of many international anniversary exhibitions – 100 drawings have travelled to London, where they are displayed in largely chronological thematic rooms, interweaving the stories and progress of each artist.

[image3]

It remains unclear when the artists met for the first time, but it is known that between November 1910 and January 1911 they made several studio visits to one another. Schiele asked Klimt if he could have one of his drawings, proposing to trade several of his own for one by the elder artist, to which it is said that Klimt responded: “Why do you want to trade drawings with me? You draw much better than I do, anyway.” Klimt nevertheless made the trade, going on to buy several more of the younger artist’s works.1 Schiele also visited the morgue to make three drawings of Klimt’s “much changed”2 body after his death. Sadly, these sketches are not included in the exhibition.

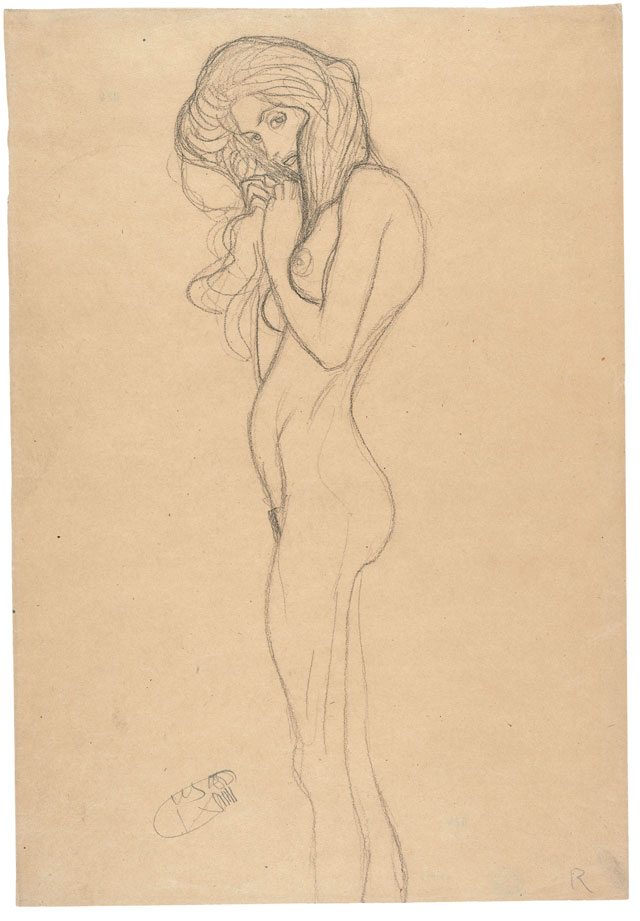

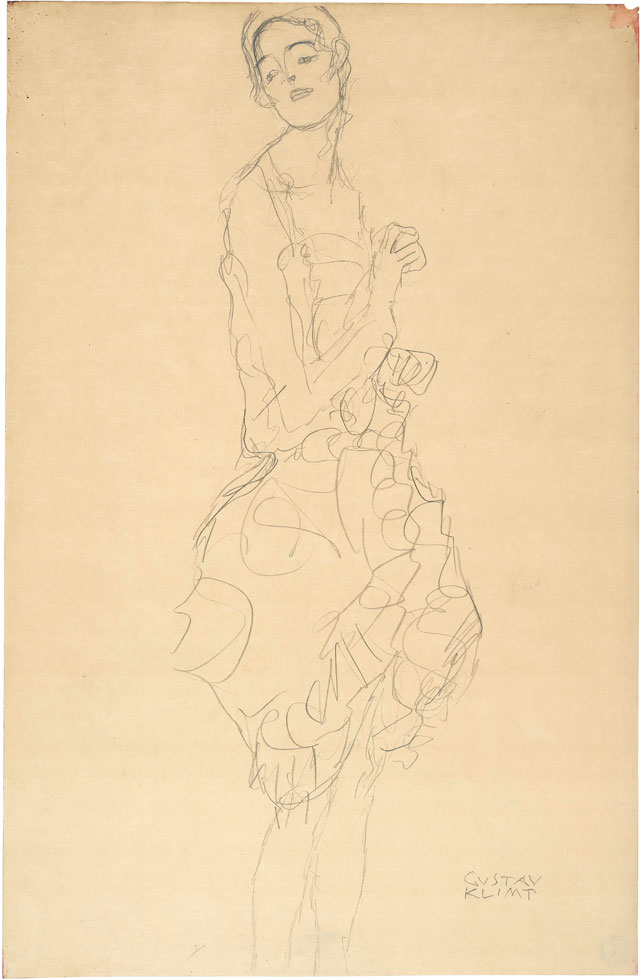

Unlike Schiele’s drawings, which were typically not studies but works in their own right (some of his sketchbooks, in which he worked out ideas for paintings, are included here in a vitrine), Klimt’s drawings were usually related to his paintings. Some of his studies for his early commissions in Vienna, including his so-called “Faculty Pictures” – in fact, his first depictions of the nude body – are included here, sketched on packing paper. His studies for Medicine are smooth, simple and classical, showing the influence of the ancient Attic artists. There is no crosshatching or shading, just a build up of clean, curved and sinuous lines, all flowing in one direction. Likewise, his study for the Three Gorgons from the Beethoven Frieze (1901) shows stylised figures with pronounced bodily contours, slender yet sensuous, seductive femmes fatales.

[image2]

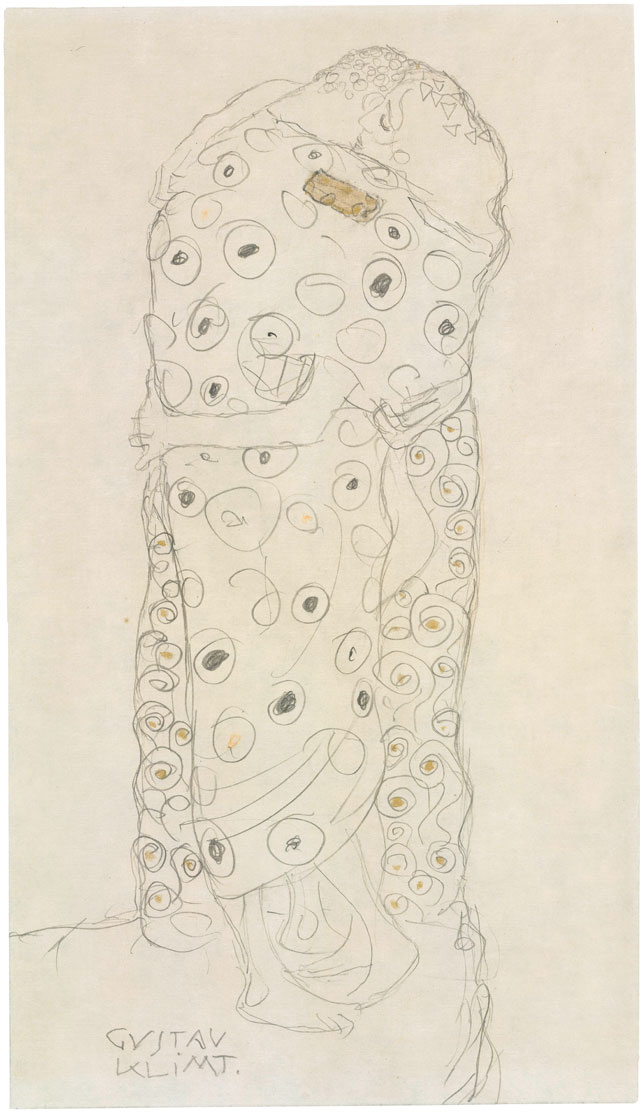

An early nude by Schiele – Reclining Female Nude (1908) – while already departing from the academic style, similarly uses simple, clean and classical lines, more decorative and ornamental, influenced by the Jugendstil, than the tortured, emotional style he would go on to develop. The Painter Anton Faistauer (1909), which employs the secessionist square format, includes a patterned armchair, inspired, no doubt, by the similarly composed works of Klimt’s “Golden Period”. Nevertheless, the hands and sleeves already show signs of Schiele’s own erratic, edgy and broken-lined style.

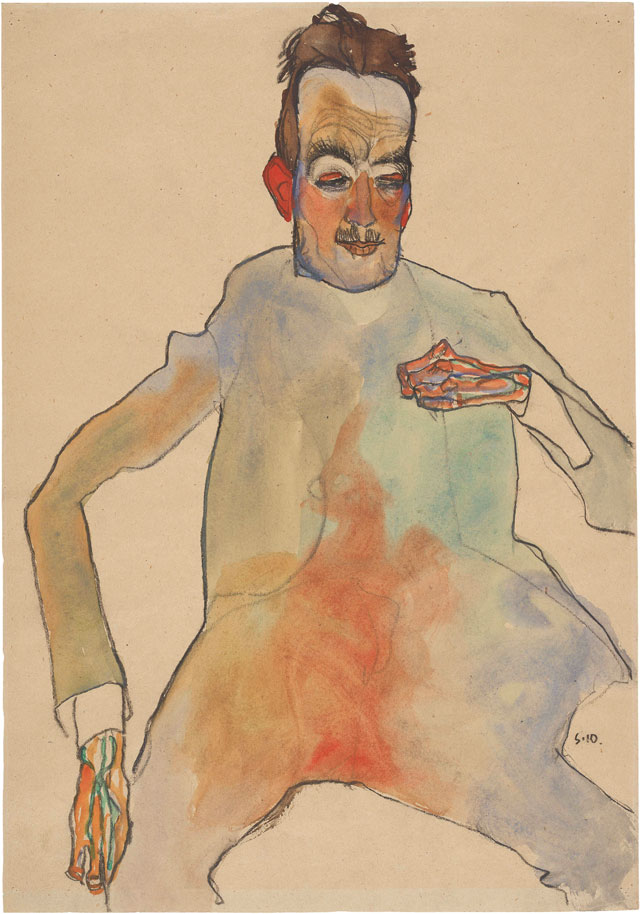

Moving away from this use of patterning, Schiele frequently employed watercolour and gouache in his works on paper, always added later, from memory, and more as a graphic compositional device than to create any sense of three-dimensionality. The line remained his organising principle and energetic force, and his drawings were always closely observed from life, his models scrutinised. In his final year of life, the artist had more than 177 sittings, his notebook recording up to 31 daily appointments with different models. In 1909, Klimt included some of Schiele’s “somewhat derivative” paintings in the Kunstschau; the following year, however, Schiele had his first solo exhibition in Vienna, and this is credited by the curators as the year in which he found his own style.

[image4]

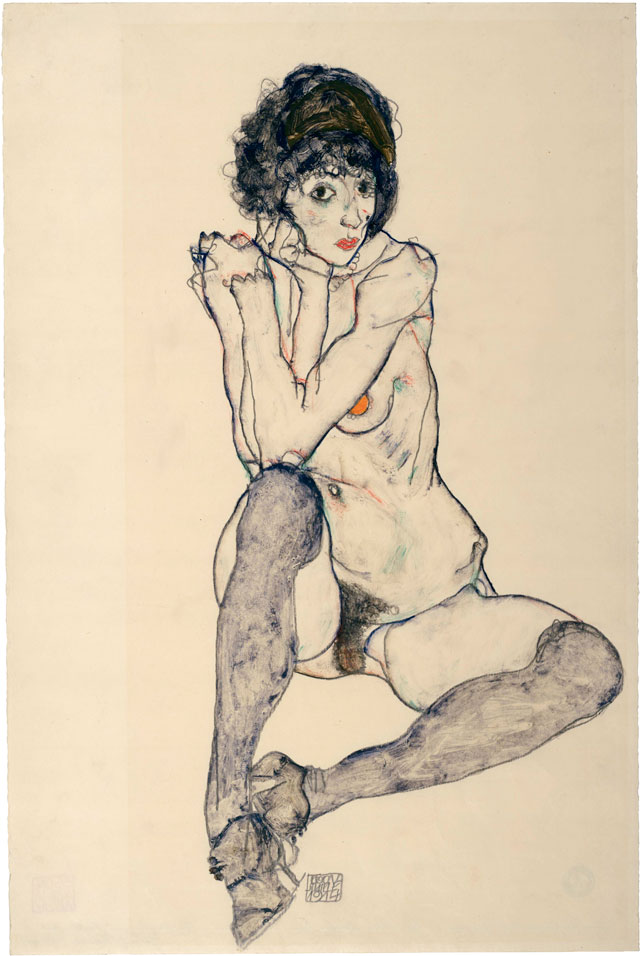

His Female Nude and Female Nude Seen from Behind (both from this year, and drawn in the same sitting), are augmented with white gouache “outlines”, or “auras”, which Schiele described as “inner light shining forth from the bodies”. He was, at this time, interested in theosophy. Black-Haired Nude Girl, also from 1910, is remarkable for its provocative pose, direct gaze (most of Klimt’s masturbating women are absorbed in their own pleasurable activity and do not look out to challenge the viewer) and heightened red lips, nipples and labia. With the age of consent as low as 14, and this model clearly not much older, the image captures the turmoil of adolescence.

It is easy to imagine one of today’s young, overly sexualised teenage girls posing like this, with her hip jutting, a pout, doe eyes, and her hand to her cheek – take, for example, Rineke Dijkstra’s photographic work Kolobrzeg, Poland, July 26 1992, which, however, emanates innocence where Schiele’s exudes nascent sexuality – but even clothed, this could be a highly problematic artistic subject, particularly for a male artist. It is well known that Schiele was arrested and imprisoned in 1912 on charges of immorality and the kidnap of a minor. Ultimately, however, he was convicted only of “public immorality” for “failing to keep erotic nudes in a sufficiently safe place”. In the era of Sigmund Freud and his theory of sexuality (his essay on the subject had been published in 1905), the eroticism itself was clearly not the issue, nor, especially, the age of the models. How times have changed.

Some drawings from his four weeks in Neulengbach prison bear testament to Schiele’s compulsion to sketch, no matter what – his subjects here being the prison corridor with its mops, brooms and buckets. One work, dated 20 October 1912, is annotated with the words: “Nicht gestraft sondern gereinigt fühl ich mich” [“I don’t feel punished, rather cleansed”].

[image5]

As an emerging artist, Schiele needed patrons, and the eminent architect Otto Wagner advised him to paint a series of portraits of famous Viennese personalities and exhibit them in order to attract further commissions. Schiele was, however, unable to fulfil this direction, since the style of such a public commission was so at odds with his own burgeoning aesthetic. Included in the exhibition, however, are a couple of portraits of Gerti Schiele, the artist’s younger sister, from 1911, around the time when he visited Klimt’s studio, and they show the elder artist’s influence in their delicate but sharply defined pencil lines. In 1915, Schiele married Edith Harms, largely for social reasons, and simultaneously cut all ties with his former muse and lover, Wally Neuzil. His style changed to become more realistic, with softer, less hectic lines, as exemplified by Edith Schiele (1917). The portrait of a child, Maria Steiner (1918), however, is, for me, a step too far, and doesn’t work at all. The air of innocence seems kitsch and the image merely illustrative, with none of the existential anguish that plagues and enlivens his earlier works. To a lesser extent, this is also the case with his portrait of Edith: although endearing and beautiful, it is somewhat complacent, with no hint of the struggle of living, so apparent in – and key to – the rest of the artist’s oeuvre.

Fewer of Klimt’s later works are included in this exhibition, but, it is worth noting how Berta Zuckerkandl-Szeps, a journalist and friend of the artist, remembered: “In order to ensure that the virtuosity did not take over from the naive, heartfelt interpretation of the material, the master began drawing alternately with his right and left hand. This is why the drawings from his last years are so magnificently intense.”3

While no self-portraits by Klimt are known to exist – he spoke freely of his lack of interest in depicting himself – Schiele frequently portrayed himself and left behind 170 self-portraits in pencil, watercolour and oil. He played on his belief that a coherent sense of self was threatened in the modern era and, in Self-Portrait (1914), reduced himself to his bare bones, with the lines of his ribs extending beyond the outline of his torso, and deep, dark eye sockets, exaggerating his skinniness. His ear is depicted as one single curved line, while the curls of his hair – on his head, in his armpits, and around his genitals – are tightly sprung.

[image6]

The final room of the exhibition brings together some of each artists’ more taboo-challenging, erotic drawings, including Schiele’s Standing Female Nude with Raised Shirt (1913), radically cropped, even halfway across the foot, with the focus purely on the revealed genital region, almost in the centre of the composition, where the shirt is lifted. Here, the red heightening is of the seemingly random space between the arm and the trunk of the figure – highlighting a very different kind of aura from the earlier white. The work is graphic in both senses of the word, although, oddly, the genitals themselves are less explicit and more modestly hidden than in many of the other works.

From Klimt, there are drawings he made to illustrate a luxurious edition by the Wiener Werkstätte of a translation of Lucian of Samosata’s Dialogues of the Courtesans from the fifth century BC, as well as his Study for “Water Serpents II” (Second Version) (1905-06), described as depicting lesbian love. When shown at the Galerie Miethke in Vienna in 1910, Klimt’s erotic drawings were described by critics as “sick art” and “highly repellent”.4 This effort to close by reinforcing the risqué nature of both men’s work seems somewhat unnecessary, since, what the rest of the exhibition has shown, is just how beautiful their drawings are, regardless of whether they depict an agonised self, a masturbating, underaged girl, or a corridor filled with brooms and mops in a prison.

It is each artist’s use of line, his sense of composition, and his spontaneous evocation of something at once complex and elementary, beyond our comprehension and yet mundane, sublime and, as I say, simply beautiful, that makes their work and legacy so enduring. So, to return to the often-slapped-on label of Klimt and Schiele as producers of erotic – or pornographic – drawings, is somewhat disingenuous in my book. While, in essence, it may well be true, it is diminutive, since, as Klimt himself so bluntly put it: “All art is erotic.” And this exhibition commemorating their work – and the centenary of their deaths – is, first and foremost, about wonderful art, not just erotica.

References

1. Quoted in Erinnerungen an Egon Schiele: Marginalien zur Geschichte des Menschentums eines Künstlers, by Arthur Roessler, published by Verlag C Konegan, Vienna, 1922, page 49. Cited in Obsession: Nudes by Klimt, Schiele and Picasso from the Scofield Thayer Collection by Sabine Rewald and James Dempsey, exhibition catalogue, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2018, page 51.

2. Ibid, page 42. Cited in Obsession: Nudes by Klimt, Schiele and Picasso from the Scofield Thayer Collection by Sabine Rewald and James Dempsey, exhibition catalogue, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2018, page 51.

3. Einiges über Klimt by Berta Zuckerkandl-Szeps, 6 February 1936. Cited in Obsession: Nudes by Klimt, Schiele and Picasso from the Scofield Thayer Collection by Sabine Rewald and James Dempsey, exhibition catalogue, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2018, page 37.

4. On the Limits of the Exhibitable: The Naked Body and Public Space in Viennese Art around 1900 by Tobias Natter. In The Naked Truth: Klimt, Schiele, Kokoschka and Other Scandals, exhibition catalogue, Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, 2005, page 31.