by VERONICA SIMPSON

Keith Tyson (b1969) is a polymath, although his prolific interest in philosophy, astronomy, mathematical patterns, computers, algorithms and physics has also garnered him the nickname the “mad professor” or “wacky boffin” of art, because all of the above can be found woven into his work.

He first came to attention for his 1990s Artmachine Iterations, works of art inspired by a Heath Robinson-esque contraption that apparently comprised flowcharts, books, an early Macintosh computer and some electronic random-number generators. The works it told him to produce, he says, were like another art education because they suggested projects or techniques in which he was completely inexperienced. Although he gave up on the Artmachine in the noughties, he claims there are still 12,000 Artmachine proposals that he hasn’t tested.

[image2]

His unconventional route to becoming an artist has undoubtedly helped him to steer a course away from the usual art-school tropes: Tyson left school without qualifications at 15 and spent four years as an apprentice engineer at the Barrow-in-Furness shipyard in Cumbria, helping to make nuclear submarines. He left the shipyard after four years, for a foundation course at Carlisle College of Art, then a degree in alternative practice at the University of Brighton faculty of arts and architecture, but that immersion in engineering and physics, plus an early interest in computers, gave him a head start on the rest of the art world, which has only recently embraced that weird twilight area that explores the impact of technology on aesthetics, and vice versa.

That unconventional route may also be one of the reasons he goes to extraordinary lengths to research his subjects, layering in far more complex theoretical or scientific detail than may be considered necessary, almost over-justifying the attention that has attracted. For example, the show that netted him the Turner Prize in 2002, saw him assemble a huge and diverse body of works, including a Galactic Central Pointer (a finger that remains pointing at the centre of the Milky Way), a Semtex bust of Mrs Thatcher, and a pillar of computers he called The Thinker, which he described as “a comatose god running its own universe”. There were also two paintings, Bubble Chambers: 2 Discrete Molecules of Simultaneity, brightly hued works containing speech bubbles attempting to reveal the connections between two different events occurring on the same date.

[image3]

Following his Turner win, he was showered with offers, including lucrative commissions such as the two 40ft x 10ft (12.2 x 3 metre) panels he created for the foyer of a new Hyatt Center skyscraper in Chicago. He told the Sunday Times in 2003: “My idea was to sort of build a kind of molecule virtually, inside the building. It’s implying the interconnectedness of these spheres of influence in this building, which is going to have huge economic superpowers working in it.” If that period marked a fascination with the superscaled along with molecular minutiae, he is now operating at a very different level, choosing flowers, a subject that at first seems almost mundane, but rendering them in ways that are anything but. He is currently showing a series of flower paintings at Hauser & Wirth, London, called Life Still.

Life has been scaled down on many fronts for Tyson. Where before he had a huge studio and multiple assistants, he is now in a relatively modest studio in Primrose Hill, north London. He has been here for two years, mostly alone, working in paint. Although, as the interview that follow shows, there is far more to these flower paintings than simple floral representations.

[image4]

Born Keith Thomas Bower in Ulverston, Cumbria, he took the name of his stepfather, Tyson. And the issue of names and legacies is clearly a current preoccupation: he has messed with the signatures of this new series, some are signed Tyson, but in the style of the artist they are most directly inspired by. Some are signed Bower. Although science certainly remains centre stage, cultural history is asserting itself. He is represented by Hauser & Wirth, which says: “His work is concerned with an interest in generative systems, and an embrace of the complexity and interconnectedness of existence.”

Veronica Simpson: What was the trigger that got you started with these flower paintings?

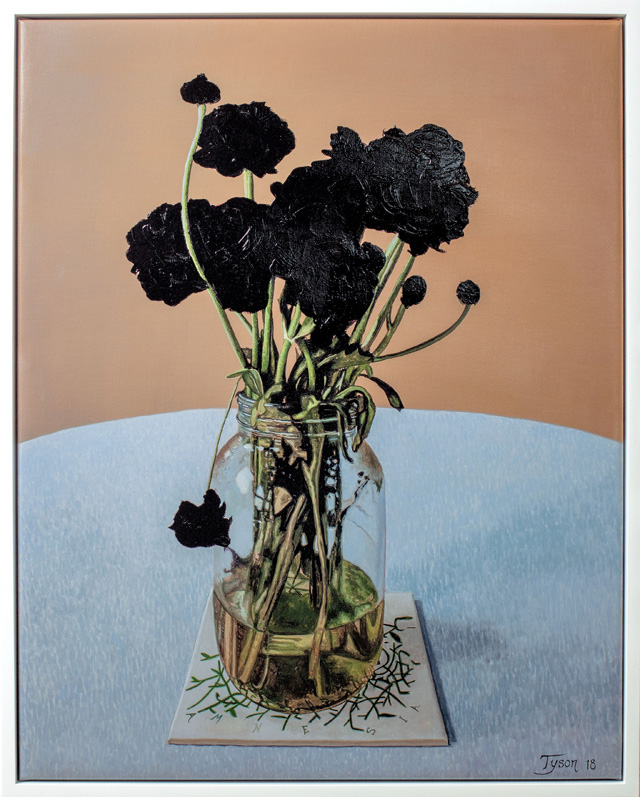

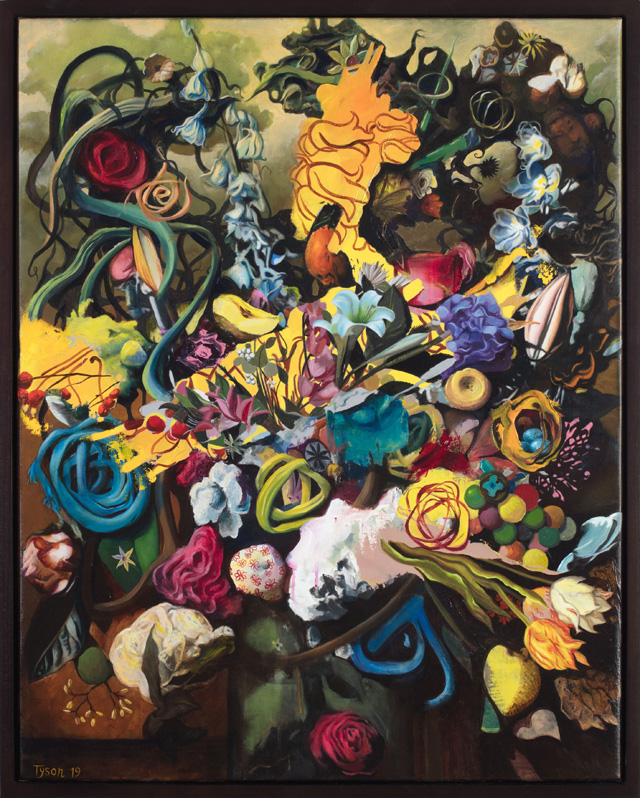

Keith Tyson: I’ve been doing flowers for a while. I started doing them when I started doing scrape paintings. I’d find an old painting in a junk shop and then I’d repair it and then scrape over it, Iike (Gerhard) Richter draws over his pictures with a squeegee. Then, where the ground is, I’d paint into that ground, and get some interference going in the surface. I’d started painting flowers into them because they didn’t have any other signification other than that they’re flowers. I mean, obviously they’re symbolic and they’ve got all this weight behind them, but generally they’re like, get a brush, get in there and get some sort of juice, and it sort of evolved from there. I got really fascinated with still life painting. How would you make a still life today? Those Dutch still lifes were all surrounded by (symbols of) the new world, exotic flowers and the merchant class and their cosmology of the time. I looked around me and thought we’re in this information age with all this stuff going on, everything’s decentralised, so how do you make still life now? Also, because I’ve gone back to my own hand, it’s quite a nice modest scale to work at. Each one is its own separate universe.

[image5]

For this show, I set off with the idea of doing two dozen flowers … They are all paintings of flowers at first glance, you know. But there are really no paintings of flowers in the show. They are paintings of surfaces and mathematics and all sorts of other things.

VS: There may have been huge significance in flower paintings in the Netherlands, as you say, in the 17th century, but these days, flower paintings – especially ones that are relatively realistic - mainly have strong associations with kitsch. Tell me how you have handled that. Because a lot of people won’t understand that there are supposed to be all kinds of references going on.

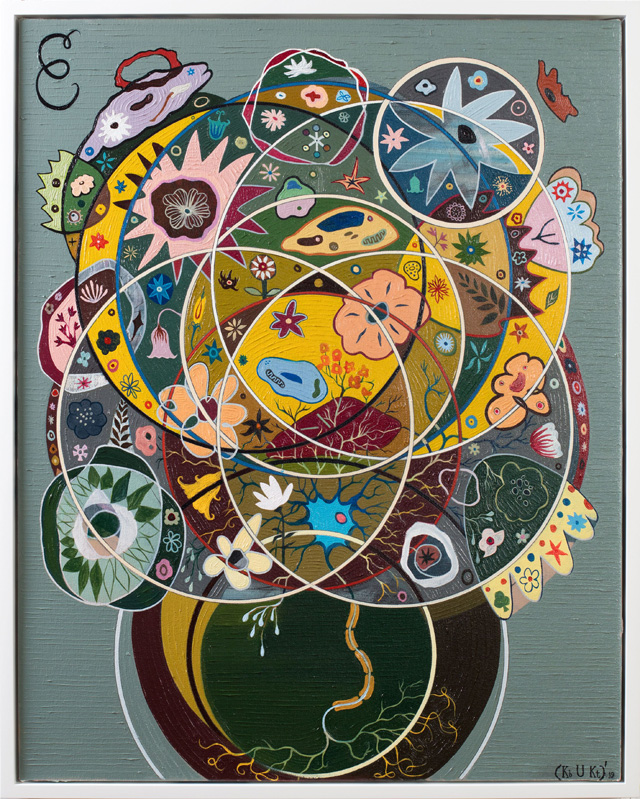

KT: I’ve looked at it cross-culturally, (including) Ikebana from Japan, Dutch still life, outsider artists and even Buddhist mandalas. The flower is really just the subject, but it’s not the content. The content is like the diversity and juice of the world. And there’s something about a flower. It’s colour, it’s there to attract, it’s a sexual organ, it has all this stuff and it just emerges: it doesn’t see itself, but it integrates with the rest of its environment. And paint uses the same technique. It’s colours [and] you can apply it in different ways. There are different species, different methods of applying the paint. It’s a bit like flower arranging, making a painting: you’re putting things together for aesthetics, but you’re also taking radically different environmental techniques and putting them together. That’s what I was interested in, and trying to keep the work settled between all those different points and never collapsing into one thing - like just becoming kitsch flower-arranging or philosophical conceptualism - just (trying to) keep it vibrating there in this space. Also, I like the idea that you make an album of paintings and they’re informed by the ones next to them. Even though they’ll all get split up. The show is like a symphony and each painting is a note in it. They’re very diverse, not for diversity’s sake, but because each one has demanded to become what it’s become while I’ve been working on it.

[image6]

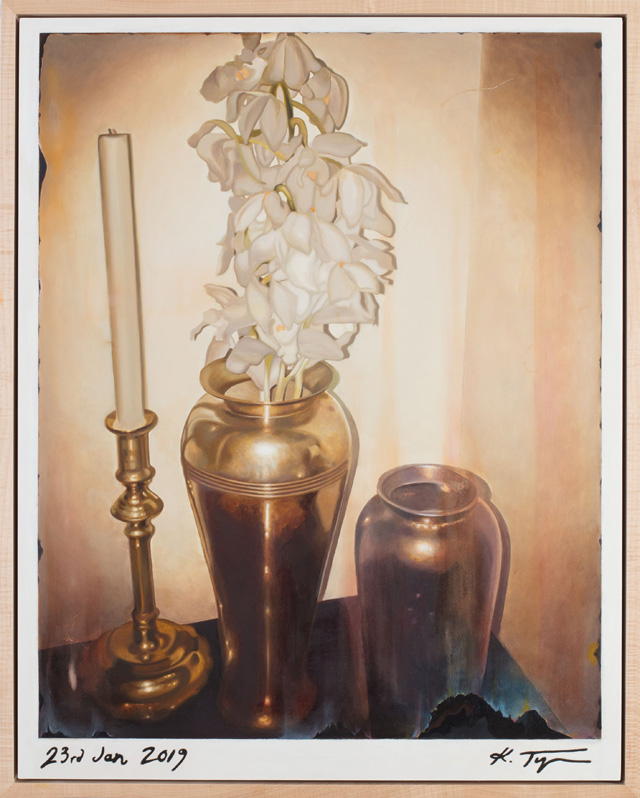

That idea of something emerging from something deeper is very much what I’m trying to do with the work. There’s this big argument in modernism about representation versus the actuality of the paint and blah blah blah. A mark is still an object in the world. An abstract painting still hurts when you get hit over the head with it. It’s still a thing. So, in this painting here – just two hours in modern time and space. And it says on it that the exact time that I painted it – 1.30 until 3.30pm GMT. The only metric for that was the time I gave myself. It’s not a painting of the flowers that were in front of me. It’s saying, at this point in time and space, that’s what occurred. And so, again, it’s flowers, but it’s a painting of coordinates of a space. I’m trying to tap into something about that mysterious quality of how things come into being

VS: Can you tell me what was going on with this one, Entropy?

KT: This was my palette while I was doing most of these paintings. Then, as I was looking at it, I thought: now I can pick out things that are beginning to look - totally accidentally – like flowers, and accentuate them. But I really got into thinking about entropy, and how the disorder of a system cannot decrease unless more disorder is created outside the system. The emergence of things that are ordered within this palette needs to have this mess outside, this pollution outside. It’s very much about entropy and a flower as entropy or a flower as romantic, or a flower as some symbol of consciousness. I’m really just exploring it. I’ve always said I find it difficult to limit myself to a style, so I have to put some restriction (around the work) and that gives me some space to explore making paintings. If they’re any good, they’ve emerged and they surprise me. They’ve informed me rather than me knowing exactly what I’m up to.

[image8]

VS: You said you might be working on several pieces simultaneously, but has the flower theme been your sole preoccupation over the past couple of years?

KT: Pretty much. I’ve been doing studio wall drawings and a few other bits and bobs. I’ve had an intense few years. The (paintings) were quite modest in scale so I could take them wherever I was and work on them. But, also, it’s like an apprentice piece. I had to relearn becoming a craftsman again. Before, I had many years of having loads of assistants and making huge pieces of work. I completely lost touch with the making. And I found it really hard. This was a way of me going: OK, I’ve got to learn to paint again.

VS: Where was the pressure coming from to make huge pieces with loads of assistants?

KT: There was a big sculpture piece I made that required lots of and lots of people working on it. I guess I got caught up in the whole … you start making a few big pieces and you take people on, and then you don’t want to get rid of them because you get to know them.

VS: Some artists find it liberating, because you can work at a certain scale and speed.

KT: No, I never found it pleasant. I was always thinking: what am I going to give them to do? And it wasn’t natural to me to do it. Before, 90% of my work was made with assistants and now 90% of my work has been made by me, and it becomes more fascinating for me to do. Now I’ve got the ability to do what I’ve always wanted to do. I was always envious of my assistants who could go home to their studio and make work. I don’t know, it was a bit art market as well: galleries and everyone wanting something for an art fair, and you just get caught up in it all.

[image9]

VS: Pressure is the flipside of success, although it’s nice to be successful.

KT: I was able to make lots of things and pieces I’m really glad I made. But the experience of doing it wasn’t really as meditative as I wanted it to be. That’s the point, really: it wasn’t communicating with the work as much. It was like: have the idea and make it happen. You have to be absolutely fuck sure that’s what you want to be doing.

I’ve had this curious mix, my degree was super conceptual: no painting, nothing. But I always was very hands-on. It was hardcore as well. Basically it was all about post-structuralism, it was impossible to make anything, a lot of things I developed were just strategies that allowed me to make something.

VS: You have come on a very interesting journey as an artist, from conceptual contemporary art to flower painting.

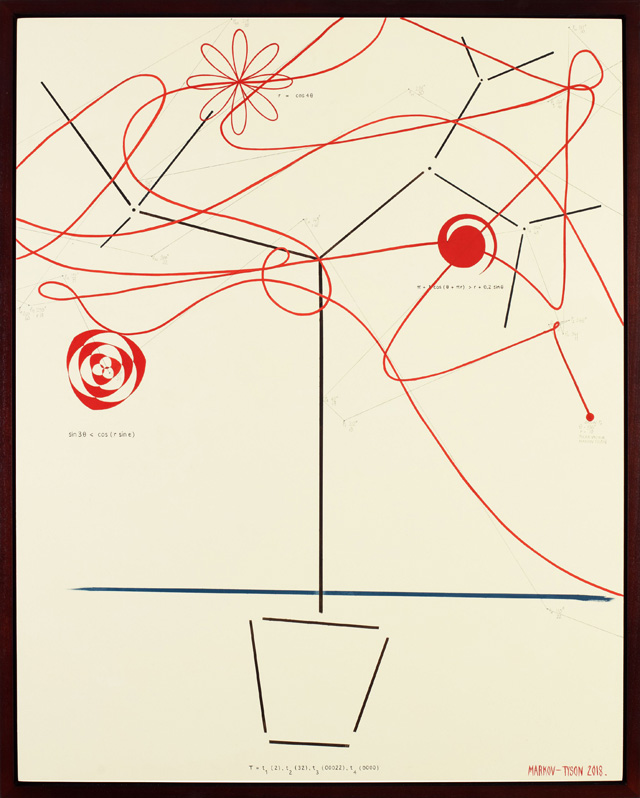

KT: I don’t know. For me, that kitsch thing is a very minor part of flower painting. I know there are many hobbyists. And actually some of the techniques I’ve used in the paintings have come off middle- American women on YouTube who do crafting. A mark is a mark, and what makes one painting look one way and another look like another? I’ve always said that paint is programmable material. You can apply to it the mythology of gestural abstraction and get your synaesthesia going and you’ll get one type of painting, and you can be Sol LeWitt and apply a different rule and get a different type of painting. The paint is transforming dependent on these different filters you’ve got going on and not all of it is conscious. And it’s vast. I’m always playing with the way something comes into being. Then you’re halfway through a painting and something else happens. They range from incredibly precise – this one is a procedurally generated rose, made mathematically on a computer, according to an equation and then put through a series of filters – to totally whimsical.

[image7]

This one is called My Ever Changing Mood, and it pretty much is that: it’s just me working with the physicality, with the paint itself, what emerges, and what reminds me of a flower. It’s literally putting paint on, re-scraping it, putting stuff on like an abstract painting. And these flowers have emerged literally from that process. Even the ones that look quite realistic, it’s just because a splat of paint reminded me of a lily or a rose or something. And then I’ve gone and found a picture of a lily and converted it. It’s like you’ve read this bouquet out of a process that’s a bit like reading tea leaves. It’s a completely emergent thing.

There are a few of them I did which I called Cyborgs, because they’re half digital and half painting. I’d take some flowers and photograph them, stick them into Photoshop and paint digitally all this stuff, and then bring them back and paint over the print, and put glazes and re-photograph it. They weren’t in the real world, or the digital world, they were somewhere between the two.

[image10]

It’s really important to me that there’s very different techniques in the paintings, so that there’s no fetishisation of one particular style, because it’s very much not about that. It’s not that flowers are the subject. What’s more fascinating to me is the world. And the paintings can celebrate and access and allow us to look maybe a little differently at the nature of how things are structured and how things come into being … and still celebrate that they’re made out of material. It’s still amazing to me that paint can do all these things.

When you go in looking for references, you’ve got Van Gogh and Picasso and the old masters, and you see how flowers have been dealt with over different eras. They’ve got this symbolism: they are transient, we anthropomorphise them, they really explore our condition in that way. Despite the fact of death, they do blossom. When you’re making a painting, you set off with this blank canvas, something’s going to emerge out of the dirt, the crap that you put up there. You’ve just got to have faith that it’s going to come. It’s a very celebratory thing. I’m not ashamed of that. I wanted to do a body of work that didn’t apologise for that aspect of painting - especially for someone who’s done some pretty nerdy art.

[image14]

VS: How did this Ikebana-inspired painting come about?

KT: It was probably 18 different paintings before it was this one. It was at a time when I wasn’t really sure what I was doing anyway. I started doing this gestural thing, this reading in it. And then I started seeing a form and that’s when I thought Ikebana, which is a complex form of Japanese flower-arranging, and got some maths for Ikebana, and put it in and got it to grow organically from the root. This one’s called Ikebana Waterfall Stage Boss Level. Waterfall stage is obviously the background. Then it reminded me a lot of the kind of Chinese ancient allegorical paintings about enlightenment. I went and found some of those.

VS: Who is this tiny figure that crops up at various points?

KT: It is taken from something called, I think, the Hunting of the Bull, it’s a set of Chinese plates from the sixth century. This guy is travelling along, he goes past a waterfall, sees a bull, chases the bull, then he transcends the bull. The bull would represent enlightenment. As an analogy with the painting, it’s about when you get to a point where you’re not trying any more and the painting is painting itself. But it was also a bit like a video game, with Super Mario and this (the top of the painting) is the boss level. What I’m trying to do is collide a series of different worldviews on to one canvas. I’m using the language of abstract expressionism, Ikebana, Chinese enlightenment to see if something comes out of that.

[image11]

What I like about it is that it doesn’t look like anyone else’s. It is what it is. That, to me, is exciting.

Someone once said to me, you’ve got lots of ideas. I said, ideas are easy if you’re willing to let go of the first one you had, and not identify it with who you are. I’m quite happy for the world to seep through me and for the work to just emerge.

VS: Have you got more flower paintings in you, or have you exhausted the topic?

KT: No, I’ve got a long way to go on this. I will do something until I’m not learning from it any more. The second that I’m going through the motions, I’ll stop.

VS: That’s very counter to the way some artists play the art market.

KT: Sure. I’ve never really been very good at that. I always changed it up when it was going well. But not out of any kind of stubborn resistance, just because I haven’t got any choice. I am literally incapable of going through the motions. I did four years in a shipyard, that’s it for me. I’m never going to do factory work again. And at the moment I’m still fascinated by the possibilities for what a still life painting could be. As soon as I think they’re not interesting any more, I’ll stop doing them and I’ll do something else.

• Keith Tyson: Life Still is at Hauser & Wirth, London, until 7 September 2019.