by ANNA McNAY

Having graduated from Chelsea School of Art in 2018, Kate Mieczkowska was preparing for her curatorial debut, an exhibition of works by eight female-identifying artists at Bermondsey Project Space, when the Covid-19 pandemic hit, and the exhibition moved online. Mieczkowska was not in the least perturbed and is keen to see the positives of this outcome. In the run up to the week-long online event – which will afterwards continue as a permanent website – she spoke to Studio International about the ideas behind the exhibition, some of the links she has forged with artists here and in Saudi Arabia, and her own practice and career trajectory.

[image3]

Anna McNay: Let’s talk first about your practice and background. You describe your work as interdisciplinary and, indeed, you work with many different mediums. You studied interior design at the London College of Printing, sculpture at Winchester School of Art, and then completed an MA in fine art at Chelsea School of Art. Can you tell me a bit about how you have developed your practice in terms of medium, and perhaps why you work in this way?

Kate Mieczkowska: I was always told categorically that art was hopeless, not to have anything to do with it, and to get a proper job. When I was 18, there were very few people who were successful as artists. I was at art school during the Michael Craig-Martin era, and I still never thought I would be able to operate in that world. Consequently, I kept trying to do practical things, hence interior design. But, unbeknown to me at the time, I was dyslexic, so working on a Mac constantly was just hell. I loved the drawing part of it, I could make some lovely models, but the sitting and doing all the stuff on the computer … I realised I couldn’t spend the rest of my career doing that, because I would go mad.

[image18]

I did various other things: I worked in offices, did sales. Then one day I sat bolt upright and thought: “That’s it. I’m going to do fine art.” History of art, too, because that would mean I could get a job in an auction house doing something practical. I was living in Winchester at the time, so I rang up the art school and said I wanted to study with them. And it changed my life. It was wonderful. I was interviewed by a gentleman called David Ferry, who was chairman of the Chelsea Arts Club and is now president of the Royal Society of Painter-Printmakers. He’s a lovely guy: just so bursting with enthusiasm, lots of ideas, really quite naughty and great energy. I thought: “Yes, these are the people I want to be like. This is where I want to be.” I painted well, but I was worried that if I made a painting they didn’t like, I’d be struggling. I was very lucky to meet Ian Dawson, who ran the sculpture department, and so I decided to do something different, to push myself. Ian was great. I used to run around the corridors trying to work out what to do, having a meltdown and a cry, and he would say things like: “Just breathe and think. Just make. Just do it.” It was as if all the tension had lifted. I had a ton of old images I had found in flea markets. Box Brownie images, all sorts of very old stuff like that. I put these three big pieces of lining paper up in the back of my space and started making charcoal drawings. They were huge, and it was as if all this anxiety and desire to express myself, which had been pent up for such a long time, just went on to these things. I didn’t know anything about Jeff Koons at the time, but I made this big drawing of a wolf on a pedestal, based on a little 1940s Box Brownie image that somebody had taken at London zoo. I had to do my first year part-time, but I could go full-time after that, and it was wonderful. It was the most amazing experience, and I learned so much. I met my husband and got married, and then I started a horse farm business. I had a bit of a break from art. I knew that I had to go to London, but I was not quite ready.

[image5]

Then we moved to a house close to the railway station, and I decided that would make it easier to travel back and forth to London and do an MA. I was on the train from Hampshire every day. Again, I met some amazing people. It was an entirely different experience at Chelsea, more about stepping back and thinking about my work, looking at what I could do, and being more aware of myself objectively as a grownup person, I suppose. I know what the landscape is like. I know how the professionals think, and what they want to achieve. I know about politics, and I can see where art, and possibly my art, can fit in that, and how I want it to operate. So, that’s where we are now.

AMc: You mentioned the large works you were making, the really huge drawings. I know you have talked before about some of your really large works being almost performative in the way you make them.

KM: They are. The way I feel when I’m making them, or thinking about them, or how my body is, is very much about the emotion within the work as well. They’re like portals. They are like ways into my psyche, but the size of them is human in scale. I have always loved being in front of a big painting. It’s like a duvet, it wraps around you, and you’re lost in it, just looking at it. Smaller works, too, that are just face sized, can be equally as immersive, but in a more intimate, slightly more thoughtful way. But big paintings are huge, big statements, and I love that. Whenever I go to the National Gallery or Tate Britain, I love wandering around and standing in front of big paintings.

[image6]

AMc: When you have a subject you want to work with, how do you decide whether you are going to do something small or large, or do you do them small first and then sometimes make them larger later?

KM: Some paintings, like the very big ones, can take very little time to make. And I just know. I can see in my mind how it’s going to look, and then I put it down. The less time I have to think about it, the better it is. Working on – and overworking – something on a small scale is something I’m never really very happy about. Those paintings also happen quickly and are more sketches. I put those to one side, go away and do something else for a month or two, or sometimes years, and then I get back to them and see if they are interesting or not. If so, I pair them up with something else and start building visual stories. I try to juxtapose different things. I don’t plan things out or design them. I feel through them a bit. I never really want people to see my drawings because I never feel that pleased about them. They’re my sketchbooks, except I never like to be confined to a book.

Also, I suppose I’m a bit chaotic and returning to the same thing over and over to write notes and put things down just becomes like a prison. Once I have made a big painting, I’ll clear the decks and then go on to the next project, and slightly change the set-up of the studio so it suits what is happening in my mind with the new painting. It’s not like redesigning it and changing all the furniture, but just taking the paints away. When you’re working on that scale, the way you set the room out, what you mix the paint in, the colour coordination, different pots, and how you have them so that you can work intuitively at speed, is important. Nobody ever trained me to make a palette or a sketchbook in a certain way. I like the flexibility of changing the way I work over time.

[image7]

AMc: Can you tell me a bit about the paintings you are working on at the moment, inspired by members of your family, but situated very much in contemporary times with a discourse around current sociopolitical issues? Are you working from photographs or purely from memories?

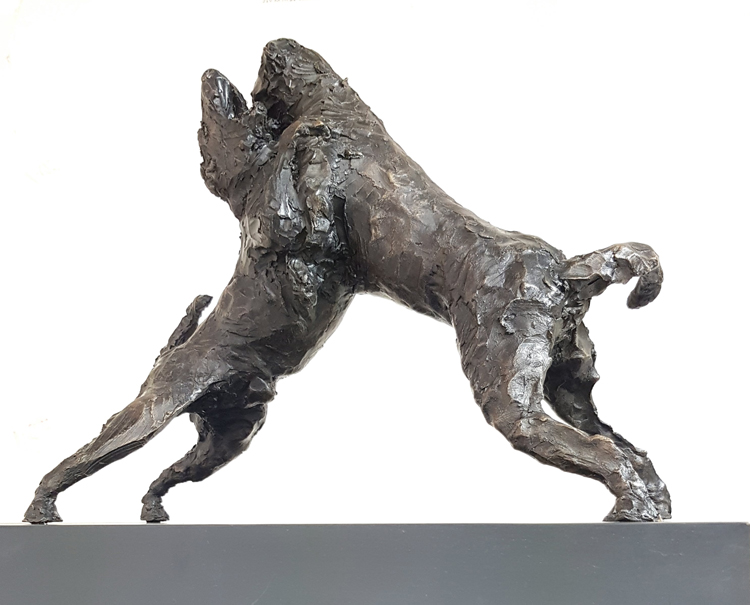

KM: Both. I have visual information and memories and things that describe situations. There are all sorts of little elements that I bring together to make the work. But they will always mirror what’s happening at the present time. Recently, with all the extra time I have had to spend in the studio, I have been able to react quite quickly to some of the things that have been happening politically, which has been great. If I have a strong sense of how I feel about a certain thing that happened politically, I look for a way to describe this that is beyond the anger. I’m always trying to look for ways beyond the anger. We need anger in order to stir up a more cerebral kind of approach, but it is frightening when you come across it time and time again. It is so negative. There are waves of it coming at you every day. That’s what the sculpture Monument, with the two fighting dogs, is about: this constant conflict. I thought, if I put that in a small room, a small dark space, and get people to walk into the space and just be with it, how will they feel? That’s how I feel about social media most of the time. It’s like watching two people in a dogfight.

AMc: Can we consider another concrete example? Maybe Revolution (2020), which shows you and your great-aunt Jill on a carousel. Can you say something about the message in that work, or what you had in your mind when painting it?

KM: Well, there are lots of things. The first things hark back to my time on my MA when we were told categorically that to be an older woman in the art world was hopeless. We were told not to even think about putting our dates of birth on our CVs because we wouldn’t get looked at.

[image13]

There is a kind of joy about being old in this painting. There is also a risk element. My great-aunt was 90 when she rode that carousel, and she loved it. That particular expression that she had comprises an equal amount of joy and fear. For somebody of 90 years old to be experiencing that sort of duality of really strong emotion is wonderful. Then there’s me – a very young me – sitting in the middle, blissfully unaware of all of this, just going along for the ride. She’s taking all the emotional strain. It’s a comment on the different generations, and how older women are so important. She’s on the outside of the circle. She’s going to take whatever is coming from the other side. She is afraid, but she is still happy. She’ll probably end up falling off. She’s going to die. We are all going to die, and then the next person is going to move outwards, and be on the outside of the circle, and the same thing is going to happen again.

I think you can also look at it in terms of what is happening globally for women with regards to raising awareness. I really struggle with feminism. I don’t want to disrespect anybody, and those women from the 70s, and everyone who has come in their wake, they are wonderful people and they work very hard, have fantastic views, and we wouldn’t be here doing the things we are doing without them – but, by the same token, I don’t want to feel ostracised from my community, because I am a married woman. I have male friends. We all share the same experiences. However, I do feel very strongly that, in a certain sense, I’m quite lucky, because we can have this conversation. There are some women globally who couldn’t. In order for everybody to grow, we need to allow women to have a voice. And it is that transitional phase that is really interesting right now, and that’s kind of what the painting is about.

[image8]

AMc: That leads quite nicely into talking about the exhibition, Goddess Now, which you are curating, since you mentioned things growing out of anger, which is something you refer to in the description of that project, too. It features the work of eight female-identifying artists. How did you select them, and, perhaps first, what is the idea behind it all? What did you want the exhibition to explore?

KM: Fundamentally, we have a lot of sociopolitical problems that feed into our inability to sustain ourselves peacefully and maintain the balance on the planet. If we start to love each other, and if we start to understand each other, we won’t go to war, we won’t tear people apart, we won’t have global warming. We can live in balance. We have enough scientific knowledge now. I think if we can start to come together so that we don’t hate each other for the colour of our skin, and we don’t believe that everybody who doesn’t share our religion is a terrorist, if we don’t have all this crap spoon-fed into our heads every day, then we stand a chance of being extremely happy. I think trade is essential. I don’t think exploitation is. I look to artists who are very strong in their humanitarian work. They are principally spiritual people, looking at how to place their work very clearly in accordance with their values, for the benefit of other people. This is how I selected the artists. There is a quality to their work, which makes people think about living in a better world, or with a better frame of mind, or appreciating somebody else’s point of view.

[image17]

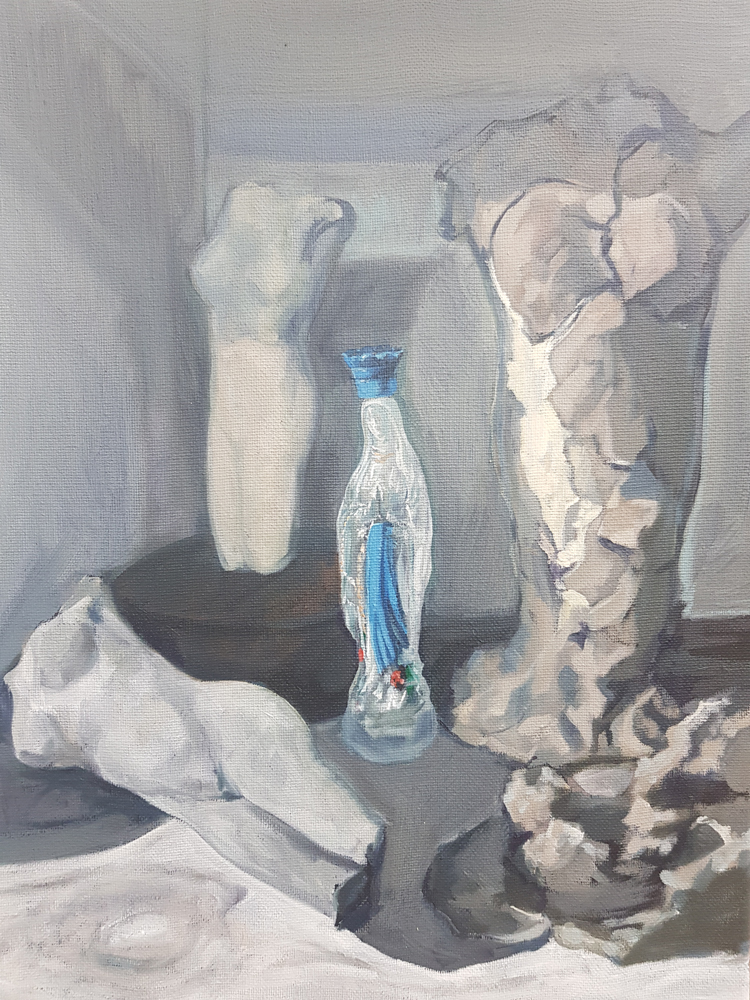

Marguerite Horner’s work, for example, is very thought-provoking. It really puts you in a spiritual mindset. She paints very prosaic things, but, suddenly, your mind will be somewhere else, and that’s a really beautiful quality. In 2014, she went on a humanitarian visit to the first Calais Jungle refugee camp with a Cenacle prayer group, founded by the Comboni Sisters from Chiswick in west London. That’s a very direct application of a clear social need. She also supports the artistic community constantly. She’s always helping people make connections and representing British art overseas. She’s very vocal in that respect.

[image20]

Then there’s a lady called Aida Murad, who is based in New York, but is Jordanian. She was an A* student, massively successful, worked really hard, and then woke up one day and couldn’t move a single muscle in her body. Suddenly, she had rheumatoid arthritis in most of her joints, and, to get herself through that and to make her fingers move, she began to paint with her hands. Her paintings are all about emotion, and they are abstract. She’s such an interesting lady. Very strong. She’s given TED Talks, works for different foundations and supports young entrepreneurs online. She’s a very active person.

All of the artists are wonderful, and, of course, the Saudi link is fabulous.

AMc: Yes, how did the Saudi link come about? I know you already had a link from when you were a child, but what brought about this renewed connection?

KM: My husband is currently working there, but, yes, I lived there with my parents when they were working there in 1977-78. My grandparents were in the diplomatic corps and were based in Israel, so we’ve always talked about, and had an awareness of, the Middle East. It wasn’t alien territory. When my husband took a job over there, I thought: “Great, I’m going to Riyadh!” Then I started to meet people and talk to them about the project and they were all really excited. There are some fabulous pieces of work being made about the second anniversary of Saudi women being allowed to drive, for example, by Ahlam Al Shedoukhy. They are very bold, very accessible, very bright, very honest paintings. She’s a doctor and lecturer. She has a family. Hers is a very real, very honest, very experimental and generous practice.

[image9]

AMc: What about the title of the exhibition, Goddess Now? What or who are you conceptualising as this goddess?

KM: It’s a collective goddess, and it’s a multifaceted goddess. It’s not an idol, it’s an ideal. And it’s about women who are sharing, working together and helping others, looking to care for and nurture not just themselves, but other people, through their work. It’s not a mission, or a religious thing, because everybody comes from different religious backgrounds, but they all have a very strong, positive message based on their experiences. It’s a very loving and very dynamic project, I hope.

AMc: Obviously, it was initially intended to be an exhibition in a physical gallery, but that’s been scuppered by Covid. I get the impression, though, that there have been advantages to come out of your move online.

KM: Absolutely. We originally planned to put this on at Bermondsey Project Space, which is a lovely gallery in south-east London, but one of the disadvantages is that, if you are disabled, you can’t get upstairs or downstairs. Also, I live outside London on a normal income, and I was always disappointed when I couldn’t get in to see my friends’ shows. Even before Covid, I was keen to make a really good website, with lots of information on it, so that people could see something of the exhibition, and maybe even talk to the artists, regardless of whether or not they could make it to the gallery. Or, if they were in the gallery in a wheelchair, they could view the work on the other floors on a tablet.

[image11]

Another thing I really wanted to make happen was a dance and movement workshop in the big courtyard space outside White Cube. I was on the verge of going to approach the gallery. I was in touch with a lady who is married to the lead singer of the 90s band James. The lead singer, Timothy Booth, has the most spooky dancing style, but he is mesmerising. And his wife does dynamic, spiritual dancing, getting people to connect with themselves. I wanted her to come from Los Angeles and do that here on our private view night. And then Covid happened. But, as it turns out, what has happened is even better. There is a lady who does drumming workshops in refugee camps, and she is going to make music specifically with a Middle Eastern rhythm. We’re going to have our dance workshop with Middle Eastern drum sounds. And it can all be done online, so anybody can join in anywhere. Then, when I’m really famous, I’m going to get it into the Tate!

AMc: Well, it’s good to aim high!

KM: One positive outcome of the Covid pandemic is the massive change in people’s attitudes towards one other. People are much kinder than they have been for a long time – and able to understand and support one another better. Within the artistic community, it has been great. The word “philanthropy” often gets maligned, but people who are philanthropists don’t necessarily have to be rich. If you can think about philanthropy in your day-to-day life and share a little bit of what you have with everybody, and they start to do the same, then we’ve all suddenly got lots. Matthew Burrows’ Artist Support Pledge is a very good example of this. It was a really good idea. I think the larger institutions need to start thinking like that. I mean, with regards to my White Cube idea, I really doubt the gallery would have said yes, and that’s really a sad way to be, because there is nothing that goes on in that space, nothing.

[image2]

AMc: You are billing the online exhibition as being a one-week-only event, but the website is going to be permanent.

KM: Yes, it’s going to develop. We’re going to keep adding to it. And, hopefully, we are going to have a physical exhibition next year. As things go along, and more people write about it and talk about it, it’s going to gain more momentum.

AMc: Can you also talk a little about the Mother Nature video project, which is linked to the exhibition, and which you are running via Instagram?

KM: Yes, it’s basically just about people experiencing the natural world and having fun. I don’t want anything professional at all. It doesn’t require any massive technology, it can all be done and sent straight from a mobile phone to the Instagram page. Children, who see something outdoors that interests them, can film it and submit it. Adults, too. There is no age limit! We will put everything up, if the content suits the project. Over time, I am hoping we will also be able to run competitions, and it will build a lovely archive. It was a lockdown idea, really, because parents were struggling to find stuff for their children to do, and they were all going out for long walks. The idea was to get people being creative, making videos together. It’s very much about experiencing Mother Nature, the Earth goddess.

AMc: And that’s going to be an ongoing project?

KM: Yes, we’ll just keep developing it. I have managed to get some traction locally with it. We have an Arts Council-funded arts organisation in my hometown, and I’m rather hoping that, next year, when the school workshops start up again, I might be able to have something slotted into the programme. Sometimes people have amazing talent, but it’s just completely suppressed, and they don’t even realise it. I’d love to bring some of that out. Particularly in terms of building communities, and within the prison system for women, there is a huge amount of positive, creative energy, which is completely unutilised. We need to start to see art as a fundamental part of our community and our human psyche. It’s not just about being the next Damien Hirst or the next Lucian Freud. There is so much more to it than that. We’ve got to start dismantling all these limiting thought processes within the art world. It’s like being put through a cheese grater. You cut bits out and make it work and then force yourself out the other side and go: “That’s it, I’m an artist, that hurt.”

[image4]

AMc: So, it is not just about becoming a commercial superstar, it is about using art for good and for change and encouraging people?

KM: Yes, exactly.

AMc: Finally, I was going to ask you what is next, but it sounds as if this is going to be ongoing for a long time yet.

KM: Yes, I think so. I’ve been busy for the past few weeks, focusing on getting the catalogue written, having lovely conversations, and learning how to use all things Zoom. Once the show is on, and we have had our panel discussion on 2 September, we’ll see where we are, and hopefully we’ll get some funding for the physical show next year.

On a personal level, I would love a gallery to go: “Kate, you are brilliant. And your paintings are brilliant. Please can we show all of them together in our lovely space.” So, my goals? A solo show for Kate, and a continuation of Goddess Now.

Goddess Now is online from 31 August – 6 September, but the website will remain once the week is over. There will be a panel discussion on 2 September. For more information, see goddessnow.website