by LILLY WEI

Karen Russo is an artist whose mediums are primarily film and drawing. Born in Israel in 1974, she now lives and works in London. Her great interest is “the unknown” and the esoteric, as documented in scientific, metaphysical and historical studies. But most compelling to Russo is the line that divides natural and cultural phenomena into what is considered acceptable to a civilised society and what is not.

Russo has exhibited widely, including at the Barbican, the Hayward Gallery Project Space, the Victoria and Albert Museum and Tate Modern in London; the Busan biennial in Korea; Montevideo in Amsterdam; Haus der Kulturen Der Welt: HKW in Germany; Arquebuse in Geneva; and the Israel Museum, the Center for Contemporary Art and Tel Aviv Museum in Israel. She is the recipient of numerous awards and grants – from the Arts Council England, the British Council, and Israel’s Minister of Culture prize, to name but three.

Her recent exhibition, Haus Atlantis, at the Grosse Kunstschau, Worpswede (organised in conjunction with Künstlerhäuser Worpswede), closed last month. A narrative that circles Bernhard Hoetger, the controversial German expressionist artist, architect and Nazi sympathiser, it consisted of two commissioned films, Haus Atlantis and TET-Stadt, both made in 2016, accompanied by an installation of drawings and other objects.

The following is an edited conversation between Russo and Lilly Wei about her new films.

Lilly Wei: Would you discuss the origins of this project and how you became interested in Bernhard Hoetger and who he was?

Karen Russo: In 2012, I made a film about the Externsteine – a mysterious rock formation in Teutoburger Wald, in Westphalia, Germany. The film looked at new agers, right-wing nationalists, esoterics, neo-pagans and other groups that consider the place sacred, and how each of them related Externsteine’s extraordinary landscape to its own version of ecological, spiritual and political mythology. Haus Atlantis in Bremen came up in my research and in interviews I conducted with neo-folk musicians who consider the place a German/pagan heritage site. The building was designed in 1931 by Hoetger, the German expressionist artist, and was inspired by the idea that the Germans were descendants of the people of the mythological continent of Atlantis and the founders of all other great civilisations. I was fascinated by the aesthetics of the building, and the more I read about it, the more fascinated I became with it and Hoetger. The story behind it is so far-fetched and absurd; it made me think about the ways in which histories are rewritten and about how myth, irrationality and politics overlap.

LW: You went to Bremen?

KR: Yes, I visited Haus Atlantis to do more research. I was intrigued by Hoetger’s work but also confused by it – it was so allusive and contradictory. Hoetger’s Niedersachsenstein – a giant pagan-looking eagle made out of red bricks – in the town of Worpswede, is the greatest surviving expressionist monument in Germany. He is hailed as a local hero in north Germany, but he was also a Nazi sympathiser and a party member. However, the Nazi party rejected his art; it wasn’t interested in his vision of an idealised world based on Nordic folklore.

Here was a more complicated version of history, one that transcends an easy reading reliant on stereotypes of expressionism as a degenerate art banned by National Socialism. I was most interested in the decade ending in 1936 when expressionist fascination with archaic and primal forms, ancient cultures and ideas such as origin and roots, appeared alongside terms such as Germanic, Nordic and soil. The result was a complex overlap between political, religious and esoteric nationalist beliefs with artistic ideas about irrationality and nationality.

LW: How does this project fit within the continuum of your practice? Do you think your work can be categorised within a certain genre? Is it science fiction, myth, or is it historical?

KR: Many of my previous works investigated ideas that complicate our grasp of reality through suggestions of the unknown. I tried to construct situations that would exemplify threshold states and examine the boundaries of what can be known and expressed while highlighting landscapes and characters marked by western society as belonging to the realms of the irrational, undesirable, or repressed. The current project continues some of the themes I explored in my film Externsteine, looking at how the dominance of the rational and civilised can lead to a regressive, escapist desire for myths and symbols.

LW: An earlier project of yours that I saw in Tel Aviv was based on remote viewing.

KR: I was investigating alternative modes of perception and consciousness, examining spiritual modernist ideas through the prism of remote viewing – the psychic ability to perceive invisible targets through extrasensory perception, developed by the CIA during the cold war for intelligence-gathering purposes. Haus Atlantis and TET-Stadt was a continuation of my interest in how culture intertwines the rational with the obscure. I’m interested in the dividing line between what is accepted as the legitimate expression of culture and civilised existence, and what falls outside it. I’m not sure if my work can be categorised within a specific genre as much as it reinterprets and manipulates or questions certain genres of film-making, such as documentary, sci-fi, the post-apocalyptic and archaeological essay.

LW: Could you describe the installation? Were there just the two films? And how were they shown in relationship to the architecture of the venue and each other? Did you want to create an immersive, theatrical experience?

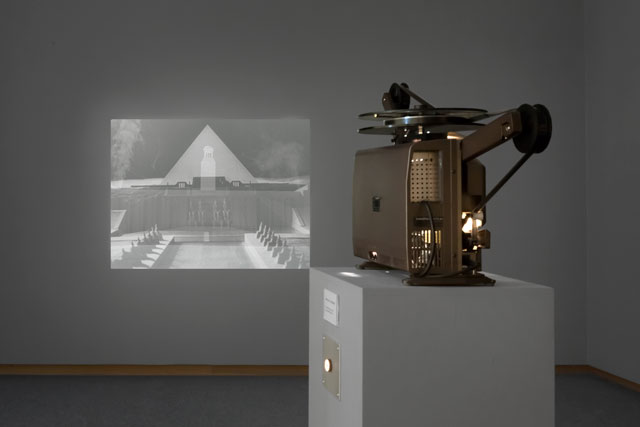

KR: The show occupied the Grosse Kunstschau’s main space, which I divided in two. With the films, I showed charcoal drawings and production stills in a vitrine. I was interested in creating an immersive environment in which the drawings become part of the installation, but I also wanted to allow the viewer to focus on each film, hence the partition. The visitor encounters the 16mm projector showing TET-Stadt first, then moves into the second space where Haus Atlantis is projected on a big screen. Capturing the audience’s attention can be problematic in a gallery. I try to find ways of encouraging the viewer to watch the whole film by having a button for the viewer to press to start the film at the beginning (it stops automatically at the end) and informing the viewer how long the film is. With Haus Atlantis, I used cordless headphones, so the sound was very direct, very immersive.

LW: Would you give us a synopsis of the narratives of the two films, Haus Atlantis and TET-Stadt?

KR: In my films, I tend to mix archival footage with new materials, documentary and fictional narratives. Haus Atlantis is a mysterious expressionist building commissioned by the industrialist coffee merchant Ludwig Roselius. Conceived as an exhibition space for Roselius’s collection of prehistoric artefacts by Hoetger, it functioned as a cultural foundation that sought to embody racial superiority through a combination of Nordic and pagan mythology, pseudo-science and futuristic architecture. The building was heavily damaged during the second world war, and only partially restored. It has since remained in a ghostly state of incompletion and now forms part of a Radisson hotel, where it is being used as a conference venue.

Shot in Haus Atlantis and nearby Worpswede, my film weaves together the marshy landscape of the German countryside with the mystical architecture of Hoetger. This is juxtaposed with footage of Roselius’s collection and staged scenes with actors shot around Hoetger’s Niedersachsenstein monument. The narration is poetic and sets the film in the future after a disaster has befallen the planet and the seas have retreated. A strange “seasickness” begins affecting large portions of the population, who are convinced that they had once lived in Atlantis. The end of the Deep Sea Age is marked by awareness that man had committed an evolutionary crime – that by travelling to the bottom of the sea, he tampered with the elements of his own consciousness. By blending elements of documentary, archaeological essays and science fiction, the film looks at the ways in which histories are altered. It invites us to reflect on the power of the cultural archetype in a contemporary context and examines the state of a social consciousness in transit between a collapsed past and a utopian future.

LW: And TET-Stadt?

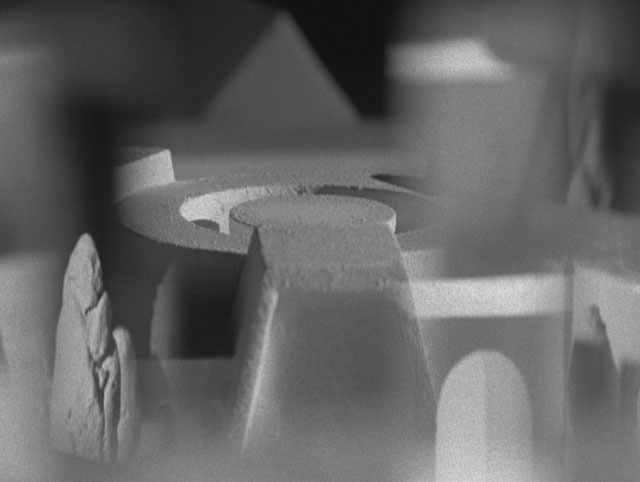

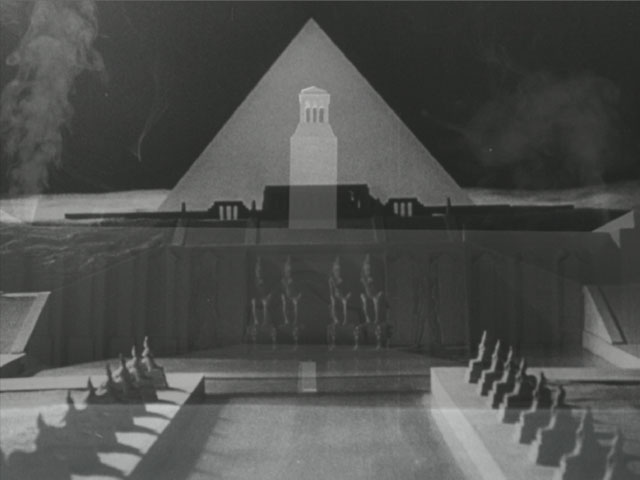

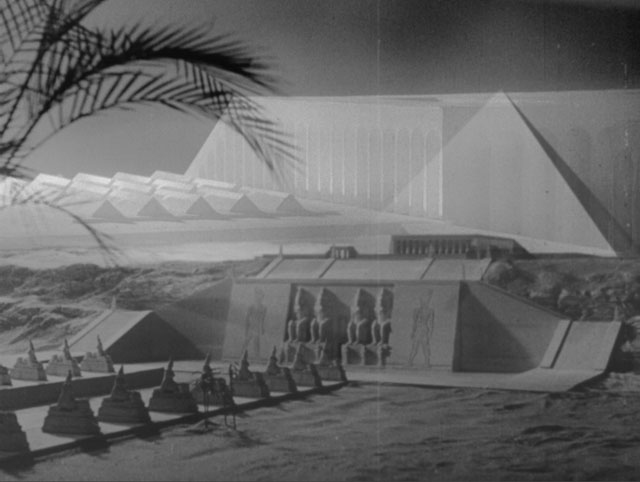

KR: The second film looks at TET-Stadt, an unrealised urban project conceived by the German biscuit manufacturer Hermann Bahlsen. TET derives from Egyptian hieroglyphs; it stands for “everlasting” and is still the Bahlsen logo. In 1917, Bahlsen proposed a massive industrial and residential development in Hannover to house the operations and employees of the Bahlsen company, in which all the buildings would be based on ancient Egyptian religious and secular structures. Hoetger built an elaborate model of the site, which was exhibited in Kunstverein Hannover in 1917, but was lost during the second world war.

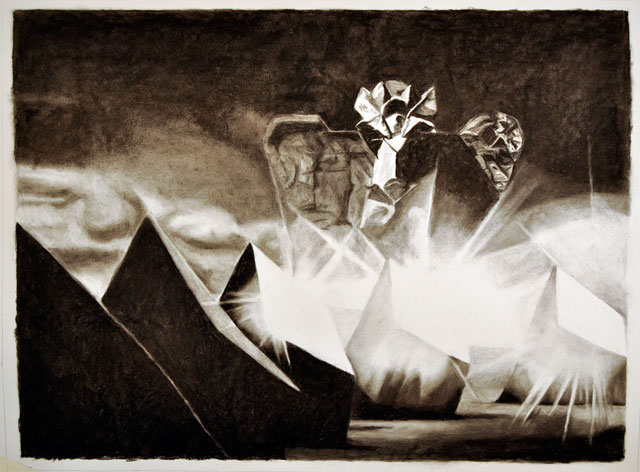

My film was shot inside a large-scale recreation of this model that I based on the architectural plans and photographs of the original model. The film consists of an abstract synchronised movement across the model to create a dynamic play of light, shadow and reflection. These shots are intercut with extracts from Germanen gegen Pharaonen, a propaganda film from 1939 by Anton Kutter, in which lay historians discuss the possibility that the Egyptian pyramids were of Germanic origin.

LW: And the relationship of Hoetger’s two projects to each other – how are they similar and different?

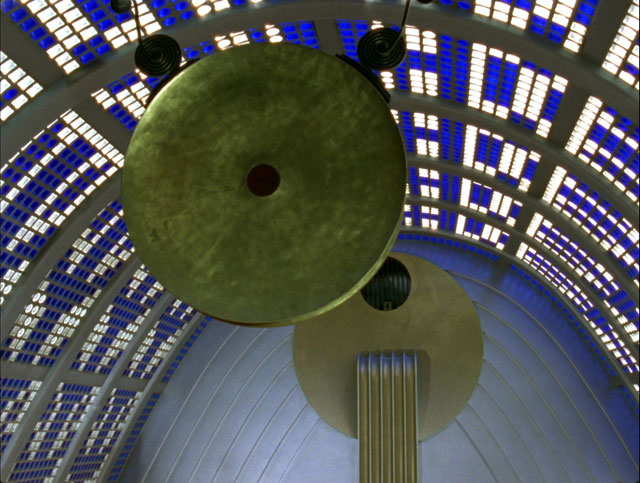

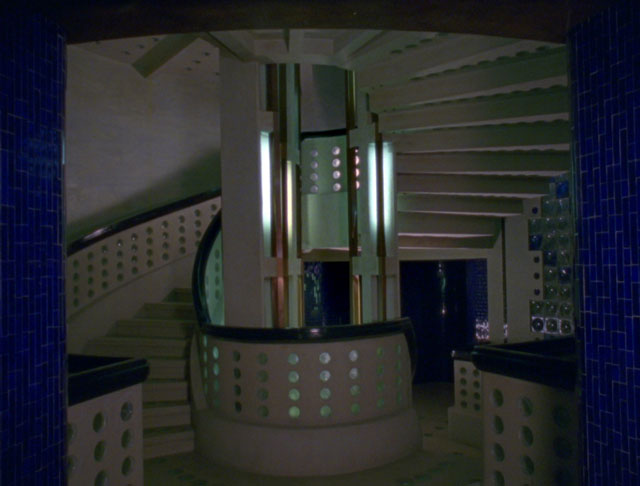

KR: Hoetger spent his life tirelessly seeking inspiration in different cultures and traditions – Asian, Egyptian, pagan and primitive. TET-Stadt was an unfruitful attempt to build such an amalgam for the machine age. In Haus Atlantis, however, all these disparate artistic motives finally appear to unify: on its facade, Hoetger incorporates the pagan tree of life, which he has already included in previous designs. Now he combines it with a crucified figure within a wheel of life. The ultramodern stairwell, built with blue glass bricks and concrete, leads up to the Himmelssaal (hall of heaven) – a futuristic sprung-arch construction with a solar disc on its front face, which, in its pure abstraction, recalls the sun symbols of the Egyptian “heretic Pharaoh” Akhenaten.

But TET-Stadt was particularly impressive to me for its sheer ambition. Both Roselius and Bahlsen were wealthy businessmen who tried to use the power of cultural archetypes to effect social consciousness. I found it amazing how ideas that looked seemingly harmless in 1917 (albeit deluded and ridiculous in their grandiosity), were transformed within 20 years to form a dangerous ideology.

LW: Would you talk about the philosophical implications of that architecture at the time, its propagandistic functions and how it bolstered the idea of Aryan supremacy?

KR: TET-Stadt’s design was influenced by a wave of Egyptian revival architecture, art, and design that swept Germany in the beginning of the 20th century, and Hoetger was influenced by all of this. Added to the revival was the notion of utopia. Some German expressionists were drawn to a search for rural utopias. Many others, however, saw utopias in the growth of cities, and great potential in new building techniques based on steel and glass. TET-Stadt was part of such a movement, a utopia that could be constructed in culture rather than discovered in nature. Bahlsen’s business model of enlightened industrialism combined technological innovations with a conviction that the world of art should “spiritualise” commercial life. TET-Stadt was designed in a time when utopian enthusiasms had not yet hardened into political ideologies.

Haus Atlantis, on the other hand, was designed nearly 15 years later and many things had changed by then. The brainchild of Roselius, the developer of decaffeinated coffee and the founder of Kaffee Hag, he dedicated his fortune to supporting German art and culture. To promote his ideas and display his collection of prehistoric artefacts (he dreamed of a Vaterkunde museum [a museum of ancestral history], which would help to restore the self-esteem of the German people by displaying the great art made by their ancestors), Roselius undertook the reconstruction of the Böttcherstrasse in the old section of Bremen. By 1928, his philosophy was much influenced by Herman Wirth, the racist/nationalist writer and theoretician. Wirth’s notion that the explanation for Nordic superiority was because they were descendants of the inhabitants of the lost Atlantis had a special appeal to Roselius.

LW: What were some of the architectural highlights of the building?

KR: The visitor to Haus Atlantis was invited to climb up a spectacular steel and glass spiral staircase to the upper floors. Light breaking in through blue and white glass created a haunting semblance of an underwater world – a metaphor for Wirth’s theory about the rise of the Nordic race. The staircase was designed to lead the visitor through a spiritual journey, from the dark depths of the sea, where the ruins of Atlantis lay, towards the glass-roofed Himmelssaal, a performance space where light streamed in through rune-shaped blue glass patterns symbolising life and resurrection.

The facade had, as its centrepiece, the most controversial of Hoetger’s totems. In a great wheel crucifix stands a gigantic, monstrous, primitive-looking wooden sculpture of Odin, the pagan god of war, hung from the Tree of Life. Social conflict, industrialisation and war were the burdens borne by the figure, a martyr to the cause of German regeneration and promising redemption from the cataclysms of modernity. Adorned with runes, and other cosmic pagan symbols of an ancient religion, it reflected the social utopianism of expressionism in religious terms. In his choice of Hoetger to design Haus Atlantis, Roselius found a kindred spirit who shared his ideas of Germanness in the arts.

LW: What were some of your formal decisions in making the films? For instance, your use of black and white and colour in Haus Atlantis? How did that signify different eras? Is colour more present, black and white more distancing, abstract? And TET-Stadt – was the reconstruction all white?

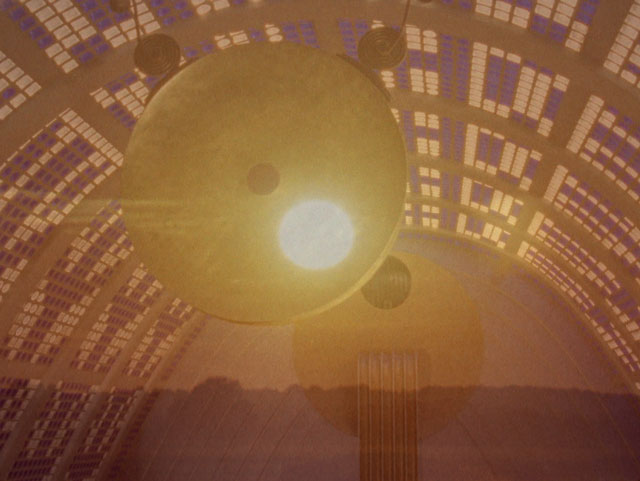

KR: In Haus Atlantis, the movement between the long-forgotten past and the far-off future (and a desire to fix or arrest that movement) forms the core of the film. You may also say that the film tries to embody it formally. It is echoed in the projected vision for the building, its present appearance (a Radisson hotel), and the striking visual dynamic of the marshes – which, albeit controlled, is an area that still exudes mystery and uncertainty. Remnants of the past also appear through documentations of prehistorical artefacts from the Roselius Collection (which was exhibited at Haus Atlantis until 1970 and is now stored at the Landesmuseum Schleswig-Holstein). Shots such as the “relic hunters” around the Niedersachsenstein monument, the abandoned landscapes of the moors, and prehistorical artefacts from Roselius’s collection were shot in black and white. In a sense, they are all materials that are ingrained in the past (a monument commemorating those who died in the first world war, prehistorical artefacts and primordial landscapes) but I used them to describe a distant future. So the use of black and white helped to unify materials from different eras and to construct a new storyline set in the future, with the artefacts and some of the landscape appearing as flashes of collective unconsciousness. I’ve always liked the idea of making films that were somehow outside of time, or at least tricky to pin down to a contemporaneous moment.

From the very beginning, I wanted to film Haus Atlantis in colour and use its blue light motif as a theme. I wanted it to be experienced as this otherworldly shrine (which together with the narration can also be understood to be the “sub-aquatic centre”). So the use of black and white helped me shape the state of the deteriorating world outside of this strange hub and build tension between inside and outside. I also find that black-and-white film helps to bring information together into a hermetic world, as there is already an inherent rhythm in it.

LW: And TET-Stadt was filmed entirely in black and white.

KR: Yes. The reconstruction was all done in white in a similar way to the original. I wanted to film it quite dramatically and use one big light source that would give it a mysterious feeling, as if it were filmed at night. I also had to think about how to film the new footage in a way that would correspond to the archival footage of Germanen gegen Pharaonen from 1939. In a sense, you can say that both films are attempting to create mythical spaces of the future; at least, that’s how I see it. They invite the viewers to reflect on the power of the cultural archetype in a contemporary context, and examine the state of a social consciousness in transit between past and future.

LW: Are you pessimistic or optimistic? Escape is suggested, but through, it seems, the destruction, maybe transformation, of all that we know?

KR: It seems impossible in our world today to not think about massive collapses, from technological disasters to natural disasters. I think my interest in post-apocalyptic narratives is related to a longing for optimism due to my ingrained pessimism. Our civilisation has developed a severe attention deficit disorder. We have lost our ability to think in the long-term, and our perception of time is so narrow that it prevents us from being socially productive. I wish western society would begin embracing projects that get people thinking beyond the mental barrier of an ever-shortening future. Long-term thinking is tied not only to a view of a better future, but also to artistic practice that encourages and rewards slow creative processes.