Museum Brandhorst, Munich

18 May – 21 October 2018

by KRISTIAN VISTRUP MADSEN

Tour de Madame is truly a painting show. That might seem like an odd decision for anyone familiar with Jutta Koether’s work – she is an artist who has never not had a performative, musical or textual element to her practice. But the first important thing to say about Koether’s paintings is that they are distinctly “after” painting, in a way that is not cynical, tentative, nostalgic, self-effacing or conservative. Rather, I mean “after” in the sense of “more”, and “more” not meaning “better”, but simply “other” - something after, more and other than painting. Jutta Koether: Tour de Madame starts from here and just leaps onwards.

[image11]

What Museum Brandhorst has mounted is a fairly classic survey; dividing the last thirty-plus years of Koether’s career into reasonable chapters based on colour, style, location and influence. There is not much to mind about this, however, since it in no way obscures the rock’n’roll factor of the works themselves, and the familiar structure allows us to listen for, and discover, their tune for ourselves.

[image2]

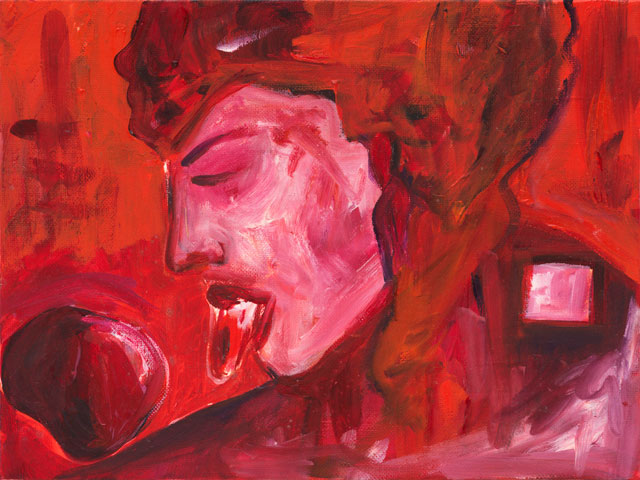

The first room features rarely (if ever before) exhibited small canvases from the early 80s in a dramatic pallet that shows the artist’s fondness for red was already established. In Straight Girl (1984), a bulky body with two perfectly round suns for breasts takes up most of the frame, while a frail face pokes out at the top. She looks almost like a rocket launching, but she is tiny (little more than A4-sized) and seems even more so surrounded, as she is, by ample white space. Across from her, a whole group of such modest proportions have ganged up – the straight girl is alone. Picasso (1983) depicts the mouth of a vacuum cleaner approaching a viscous pool of eyeballs. At the height of Cologne’s neo-expressionist turn, without gallery representation or as much wind in her sails as her peers, Koether (b1958, Berlin) used painting and the modernist legacy as a private playground. It had to be: like all its previous iterations, and as even its protagonists Albert Oehlen and Martin Kippenberger openly thematised, the return of painting to the Rhineland was strictly a male game. The works are small because they were hung in living rooms. And because Koether was busy doing other things while the oil on canvas sausage fest rode itself out.

[image3]

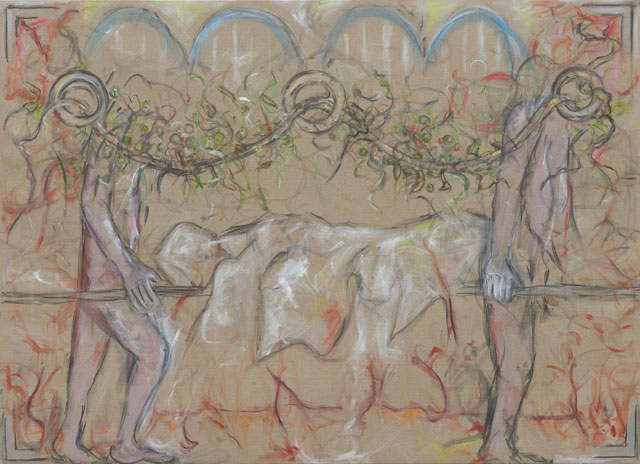

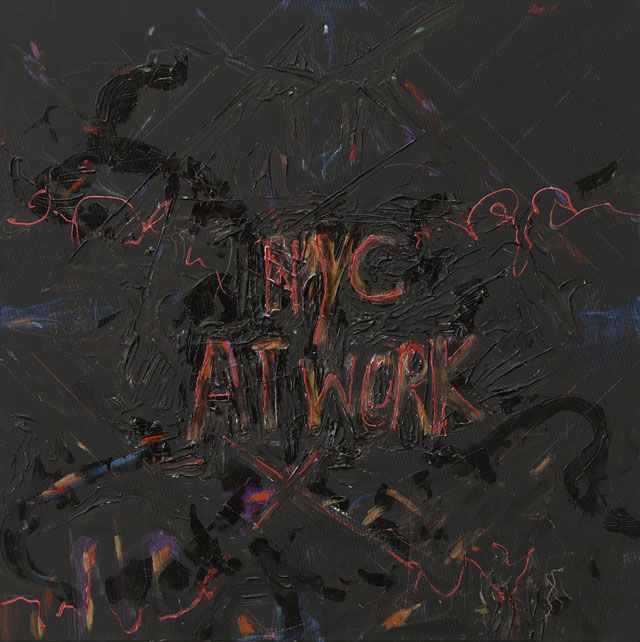

A true punk, however, Koether’s position as an outsider does not amount to victimhood, but makes up a different kind of space for creativity. In 1992, now living in New York, and again facing the lack of exhibition space available to women, she staged an Inside Job. On the floor of her Manhattan studio lay a 2 x 3 metre canvas, which she filled with swirling figures over the course of the exhibition, as she engaged with her visitors, documenting their comings and goings in a guest book. In an adjacent room, she also displayed a number of personal artefacts. By this time, Koether seems to have embraced painting in a different way – for one, the work is huge, a size that has since become her standard – and exchanged figuration for a denser, more gestural style. But similarly to the groups of small pictures of the previous decade, Inside Job does not invite a formalist reading of its surface, but a sculptural and performative one, addressing the space, time and actors involved. Here, artist and audience alike inhabit the space of the painting, which is not complete, but continuously negotiated.

[image4]

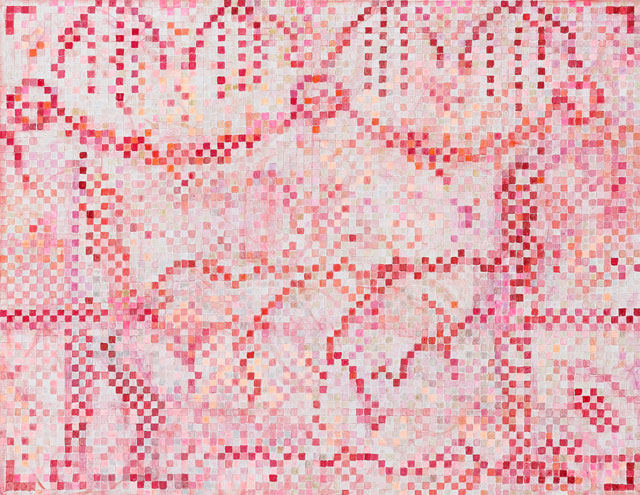

The paintings of this period want you to come up really close. Works such as 100% Malerei - Niemand ist eine Frau (1991) and the Antibody-series (1993) are saturated with green, orange and pink arabesque-like shapes, often painted over or concealing faces, bodies or even writing. If you let the composition take up your entire field of vision, the experience is one of delirious vertigo, looking through a kaleidoscope on crack. They evoke the introspective claustrophobia of Universal Wealth (1987), a suite of 86 postcard-sized paintings in deep reds hung across all six sides of a perspex box. Listing incongruent words, the backsides of the pictures face the airless atrium of the box for a cacophonous conversation with all the blabbering fever of the inside of the brain. Clearly some pressure is building up. And if what we have experienced in the upstairs galleries of the Brandhorst so far is a kind of intense chamber play or an unplugged acoustic session, what is to come is full-on stadium rock.

[image5]

In the early to mid-2000s, Koether joined Steven Parrino in the band Electrophilia, whose sound has been described as “massive slabs of electronic feedback and amplified fuzz”, attempting “to squeeze the atmosphere completely out of the room”. The paintings from this period are like the music: belt buckles, leather whips, studs, chains and cheap jewellery attached to the canvas under a layer of artificial resin, liquid glass hardened to a transparent surface. These works are too weird for me, as, most likely, would be Electrophilia’s music; they make me feel old (I’m really not). But maybe it is that track on the album you always find yourself skipping, but are somehow glad is there. Because what this body of work enacts is a breakdown and release that makes way for what follows, like fresh winds after a thunder storm – the airy works in light pinks and greens that have made Koether’s name in the past decade or so. In the series Berliner Schlüssel (2010), The Seasons (2011) and Embrace (2012), there is such jouissance, such evident ease and pleasure taken in painting, while maintaining a by-now effortless grip on the eternal “post-ness”, the self-consciousness, of her engagement with the medium. All the canvases are sprinkled with citations, frames within frames, the artist herself, and her studio. The final iteration of Berliner Schlüssel is not much more than a painted passe-partout; perfectly finished in its perpetual state of waiting for content.

[image6]

And this is how we arrive at the heart of the show: Tour de Madame (2018) is a cycle of 12 large paintings hung on a throng of monumental glass panes arranged in a semicircle in the main room of the lower-ground floor. Said to recall Cy Twombly’s Lepanto cycle (2001) – a jewel in Museum Brandhorst’s collection – Koether’s work tells an epic tale of a battle with art history and the artist-subject, packed with references from Nicolas Poussin to Cézanne and Balthus. The staircase lands in the middle of the gallery, producing an awkward shadow over the whole back of the space, and this is where the narrative concludes, with a self-portrait (inspired by Cézanne’s portrait of his wife) overwritten by Koether’s initials. Here, once again, she hammers home her point: her painting is not a surface, but a choreography, a concert, a stage. The entire room is her painting and, as ever, the artist is both omnipresent and huddled in the corner with her signature, JK.

[image7]

_2004.jpg)