Jos Tilson. Photo: Nick Howard.

by JANET McKENZIE

Most people with an interest in 20th-century British art will know the work of Joe Tilson (b1928, London). Since the 1950s, he and his wife, Jos, have lived between England and Italy and have maintained intensely productive careers. The work of Jos Tilson is comparatively little known, although she has exhibited her immediately recognisable ceramic sculptures, pots and weavings in London, Venice and Siena. Friend and art historian Marco Livingstone had known Joe’s work for two decades before experiencing Jos’s work at an exhibition at the Berkeley Square Gallery, where he bought two sculptures. He describes her work as “shaped by perceptive sideways glances at the world around her – especially in Tuscany and Venice – and by a highly poetic and subtle sensibility”.

An appreciation of architecture and modern art was instilled in Jos through her childhood. She was born in 1934 in Edinburgh, the daughter of Flavia Birrell and Alastair Morton, who ran his family business, Edinburgh Weavers, a firm that had operated for three generations, using works by William Morris and CFA Voysey for furnishing fabrics. Edinburgh Weavers was one of the most important textile companies of the 20th century. When Alastair ran the company, he invited Paul Nash, Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson to supply designs. Alastair was a gifted artist, textile designer and weaver in his own right, with a passion for art and architecture: he commissioned Leslie Martin and Sadie Speight to design a modernist house for his family in 1936.

At the outbreak of war, Flavia took the children to the US, returning in 1943. After she and Alastair divorced, Flavia moved to the village of Bishopthorpe in York. Jos attended York College for Girls and then The Mount, a Quaker school, until she was 17. Her father encouraged her to attend the Bath Academy of Art at Corsham, where she started in 1951. Her teachers included William Scott, Peter Lanyon, Kenneth Armitage and Bernard Meadows, and she recalls that the school gave equal value to music, sculpture, painting, printmaking and poetry.

After Corsham, in 1955, Jos went to study sculpture under Marino Marini at the Brera Academy in Milan, on an Italian travelling scholarship. With the help of the British Council, she transferred to Rome, where she met Joe Tilson, who was at the British School at Rome. Joe wanted her to see the Byzantine mosaics in Sicily, which he had seen in 1949. They lived and worked in Sicily for three months and were married in Venice in 1956.

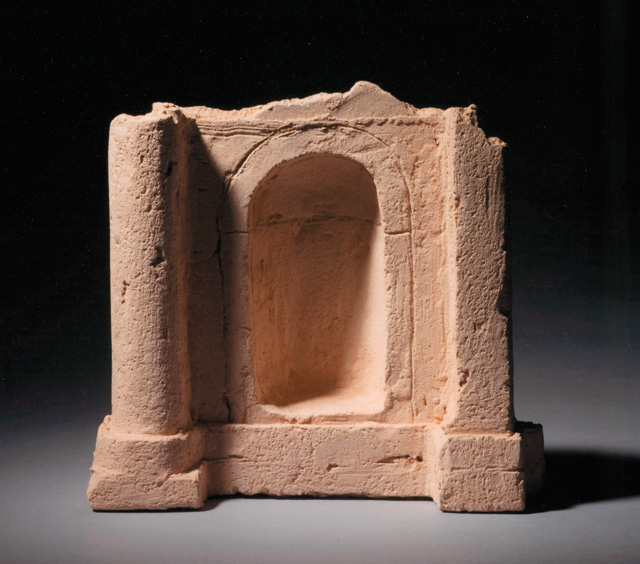

Jos Tilson. Pantheon, Rome, 1956. Plaster, 61(h) cm. Photo: Jake Tilson.

It was in Italy that Jos’s passion for architecture was fuelled and where she started to make small sculptures of buildings such as, Pantheon, Rome (1956) and Piazza san Marco, Venice (1956). Her Italian studies set in place the exploratory and single-minded creative practice that continues to this day. In the 60s, the Tilsons visited Italy every summer and, in 1970, they bought a farmhouse near Cortona, in Tuscany, where they have since spent part of each year living and working. They have three children, born in 1958, 1959 and 1965. In England, they moved to Wiltshire and immersed themselves in the environmental movement, organic food and self-sufficiency, planting thousands of trees and hedgerows and an extensive kitchen garden. Until the youngest child started school, Jos was a full-time mother. When she returned to studio practice, she made ceramics and later exquisite small-scale “pictorial weavings”. In 1982, she studied ceramics with the potter Nino Caruso, in Anacapri, Italy. She has exhibited these works in London and Italy.

Visiting Jos Tilson in London soon after the Anni Albers exhibition at Tate Modern seemed fortuitous, their careers representing many of the same preoccupations. Like Albers, since the 50s, Tilson has combined the ancient craft of hand-weaving with the language of modern art alongside an obsessive approach to sculptures in clay.

Janet McKenzie: Coming into your house and seeing hundreds of sculptures, remarkable ceramic vases and pots of all descriptions, and pictorial weavings, I realise that your creative process and your engagement with art, architecture and design must have been forged by the Bauhaus.

Jos Tilson: I have made many weavings of architectural forms. I have some weavings that are about nature, but I don’t think they are as good as the architectural ones.

Jos Tilson studio. Photo: Nick Howard.

JMcK: The recent Anni Albers exhibition at Tate Modern encapsulated the use of traditional craft techniques. All your work is handmade and tactile. In your student days, if you went to a museum show or exhibition, can you remember what you would have found exciting?

JT: I didn’t go to museums at that stage of my life. My first encounter was when I first travelled to Milan and Rome in 1955 on an Italian travelling scholarship, after completing my course at Bath Academy of Art at Corsham. A number of people have observed that my student work was influenced by Marino Marini, but I had not seen his work as early as that. I studied with Marini in Milan before transferring my scholarship to Rome.

JMcK: Your career is unconventional. You have immersed yourself in a creative career in the visual arts since the age of 17 and have produced a great many sculptures and ceramic works and many weavings. You have achieved a level of excellence and have an original vision, yet have exhibited only occasionally. No real interpretation of your work has been made.

JT: That doesn’t worry me, I just continue working. I didn’t care about not having a lot of attention. I just kept working. I was looking at some photos the other day and I realised what a lot of work I had done.

JMcK: Louise Bourgeois said in her 80s that she was glad that she had been critically ignored for 60 years because it enabled her to create a proper body of work. Your house and studio are filled with small sculptures of buildings in clay. Did you ever want to be an architect?

JT: No, but I was always fascinated by architecture.

Jos Tilson. Carità, Venice, 2007. Terracotta, 18.5 x 20 x 7 cm. Photo: Alan Tabor.

JMcK: You grew up in a Leslie Martin house in Cumberland?

JT: We were there for just a year when I was five and six, and then for a bit when I was 10. Our life there was interrupted by the war and my mother took us to America. Then, when we came back, my parents divorced, so I lived with my mother and siblings in York. My father was absolutely connected to abstract art. He was a painter and ran the Edinburgh Weavers and was passionate about architecture, so I think he must have passed it on to me.

JMcK: You have an almost obsessive work ethic?

JT: Oh, absolutely – possibly because Joe has as well, so if we’re not sitting here having a meal or listening to the radio, we are working. We were very social earlier in our lives, in London, Wiltshire and in Italy and we travelled a lot. Our life was centred on art and artists, art politics and green politics. It was the 60s, a vibrant time and there was a great belief in the future. Part of the reason we moved to the country was due to the pervasive fear of nuclear war. We were concerned with how we would eat if that happened. So we moved to the country and created a very good vegetable garden. It was still a very social existence because we had a lot of great artist friends, who also moved to the countryside around Bath. It was very hard work in the garden, and making art, but we felt very lucky to be able to determine our life to such an extent, a rare thing.

JMcK: We are surrounded by hundreds of small sculptures here in your studio and one of the recurring elements is the arch. Tennyson wrote: “All experience is an arch”; and I see them as portals to the unknown. Why are you drawn to the arch?

JT: Since 2002, we have had a studio in Dorsoduro, Venice. When I am there, I am reminded of my long love of arches. In both Tuscany and Venice, I find myself so aware of the arches everywhere and of the light coming through them: a magical osmosis occurs. They are all about light: the light leading a way through the arches – or through apertures in arches; light forming shapes of columns or bulky sides of buildings; light moving up the steps of the canals of Venice; light exaggerating the darkness of the interiors of small buildings; light making shadows from the sun shining on the campaniles. In contrast, the weavings are translations of light on to forms; they are in black and white.

Jos Tilson. Italian architecture terracottas, London studio, 2005. Photo: Jake Tilson.

JMcK: One of the immediate responses to your weavings is whether you make weavings from life as in drawings? I suppose one has to go back to the various stages involved in making weavings and how you conceive of them?

JT: When I first started weaving, I had no idea what to weave and so I used to start by making copies of paintings by Joe and other artist friends – Howard Hodgkin, Patrick Caulfield, John Hoyland and Stephen Buckley. I made a whole lot of those and, when I finished with those, I began doing landscape weavings in Tuscany – landscapes and skies. A lot of my weavings were of sky and trees. We visited Venice a lot, so I made weavings of water, the canal and architecture. That was my main source of subject and inspiration then and I've continued doing it to the present time. Yes, architecture with nature, but mostly just architecture.

JMcK: You use photography for the images rather than drawing from life?

JT: I mostly work from photographs or I weave directly at the window – it provides the framing device for the weaving.

JMcK: We have spoken before about the notion of female work: sewing, knitting, weaving within the home and within our roles as mothers (before manufacturing made cheap clothing readily available), so it makes me think that the group of large pots on the floor here by the kitchen table are, in fact, a metaphoric group of people and that one wants to hold them, to embrace them physically. They appear to me to be an extension of the female body.

JT: Exactly, but I don’t think I consciously thought that at the time of making. It was a process that just happened. Then I thought: “Oh, my God, this is just like lifting one of the grandchildren and the little handles on the side are like their little arms.” You put your hands on the side of the pot in the same way that one puts hands underneath their arms.

Jos Tilson, textiles. Photo: Nick Howard.

JMcK: You might be seen to have another family of ceramic sculptures over there as well. I would identify some of the pots and the buildings as being family groups or couples.

JT: You’re right, there are groups, probably family groups. When they are photographed, it seems natural to present the sculptures, or the human-like pots, in pairs or in groups. They look right when they are grouped and, as a sculptor, I am intuitively thinking of the way vases or other pot forms interact with others. They become sculptures when they are grouped.

JMcK: You use terracotta clay and all your hand-built pots are rounded and substantial with uneven matt surfaces. They have holes in the bottom, so they are not functional vessels. You use an earth palette: uncoloured terracotta sometimes with red or black or rusty hues made from oxides.

JT: You have made a very precise description of my work. Thank you!

JMcK: You didn’t work on your art when your children were very young?

JT: Absolutely, I was a full-time mother. That was it and I loved it and I never thought: “Oh, I wish I were doing something else.” Then I did a bit of jewellery making and was involved in art politics, but I didn’t have a studio practice. When Sophy, the youngest, went to school, I suddenly had a whole day in which I could do what I wanted. It all evolved from there.

JMcK: Did you have any help?

JT: No, not at all.

JMcK: Do you consider that, as a mother, nurturing creative talent in one’s children is a vocation in itself?

JT: Yes, because all our children are artists. Extraordinary.

JMcK: So, motherhood is a different form of creativity?

JT: Absolutely, and one which I totally believe in.

Jos Tilson. Portrait, 2005. Terracotta, 28 x 22 cm;

Portrait, 2005. Terracotta, 29 x 23 cm. Photo: Alan Tabor.

JMcK: So, the large pots that resemble the grandchildren were made well after your three children were born?

JT: Yes. When I was in Milan and then at the British School of Rome in my early 20s, I made sculptures of architecture such as the Pantheon in Rome and of trees. When we were in Sicily, I made sculptures of chickens. It was all to do with what was around me. And then my pots started when Joe taught a summer school in Anacapri and Nino Caruso was there teaching pottery. I was in my late 40s.

JMcK: That’s an intensely creative period of one’s life.

JT: I’m amazed when I look back on the sheer volume of work I did then and it enabled me to sustain a long career.

JMcK: Is being Scottish partly the reason you have such an extraordinary work ethic?

JT: Oh, I don’t know. It’s quite interesting. My father’s family lived in Darvel and for generations they were weavers. All the eldest daughters, without thinking, weave. Not brilliantly, but they all weave. My stepsister, who lives in Shropshire, is a high-level weaver in linen, a master weaver.

JMcK: An aspect of what we traditionally call female work, whether it was sewing or knitting or weaving, was that one never stopped. There was always something on hand; there were usually several projects on the go at any given time. It wasn’t a nine-to-five job, it was not something you went to the studio to do. Women would reach towards a side table and just carry on: sewing, needlepoint, embroidery; it was therefore an extension of everyday life.

JT: Absolutely, I always weave in the afternoons without thinking. I used to have my sewing machine out and I made things all the time: children’s clothing etc.

JMcK: There’s a natural fluidity between activities that seems to have an age-old rhythm.

JT: One of the problems with the #MeToo campaign is that it is beginning to marginalise aspects of being female, abilities such as sewing and knitting and mending.

JMcK: There is a counter-reaction where craft-based art is making a comeback. Grayson Perry has done a lot to value handmade artwork. What advice would you give a young artist today?

JT: Just get on with it.

JMcK: I like looking at your drawings because they are accomplished and exploratory. I wonder if you consider your sculpture and ceramics to be a kind of spatial drawing, or do you not think about them like that?

JT: Sculpture and ceramics are not a form of drawing for me. What I’m doing now is weaving and I find that it is becoming very sculptural. Weaving for me is all about shapes. I work mostly from photographs and, once I’ve thought about what to make and how to make it, I do a drawing and then I begin weaving. My drawing is a working drawing or a pattern, with dimensions, colours and technical detail to which I refer while weaving.

JMcK: Are you deliberately leaving the gaps in the weaving for that purpose?

JT: I think a “real” weaver would join up these elements of the work. Earlier on, I would have done it “correctly”, but now I leave them with openings. A stairway here, but that, funnily enough, is a weaving of a sculpture. These are of little corners in Venice. Venice is just so beautiful, everywhere you go. I get obsessions. I tend to go on and on and on. When I work on a series I take it to its full length.