MASSIMODECARLO, London

11 October – 17 November 2021

by ELIZABETH FULLERTON

Tenderness pervades Jordan Casteel’s painting show There is a Season, at Massimo de Carlo gallery in London. It’s not that the works, all painted in 2021, are sentimental, but the New York-based artist treats her subjects with a care that is palpable in the paintings. Sometimes these are strangers she has photographed on public transport, in which case she averts their eyes from ours, allowing them to retain their privacy; others are friends and acquaintances, who look trustingly out of the canvas. “For me, the gaze always starts with their engagement with me. That is what you see first, my relationship with them,” said Casteel, who was in London for the opening. “The beauty of this practice is that it allows you [the viewer] to enter a vulnerable moment that you wouldn't have been able to be a part of perhaps otherwise.”

[image4]

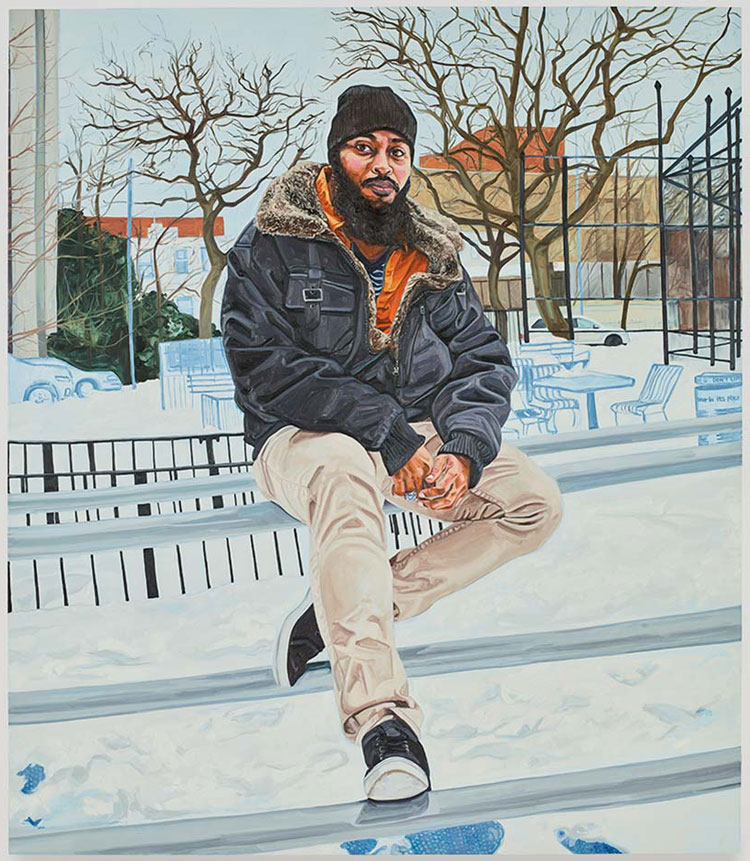

The artist, who is part of a new generation of figurative painters focusing on portraiture, came to prominence after graduating from her MFA at Yale with a series of humane portraits exploring black male subjectivity. Recent paintings have included mostly black male and female subjects, many of whom she has met in Harlem, where she lived prior to moving to upstate New York this year. Casteel dignifies her subjects with monumental paintings in which they often take centre stage. “I like to think that there’s a little room that is required for these, that people have to make room for the bodies that are represented from often marginalised communities, that there’s a commitment to get to know and spend time with them,” she said.

[image5]

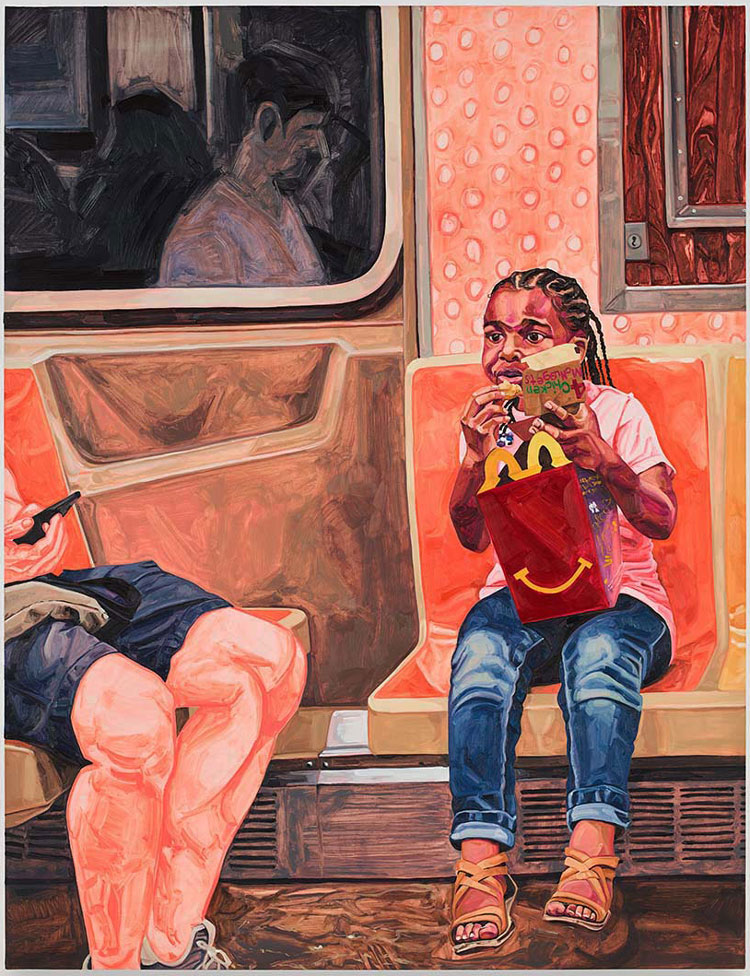

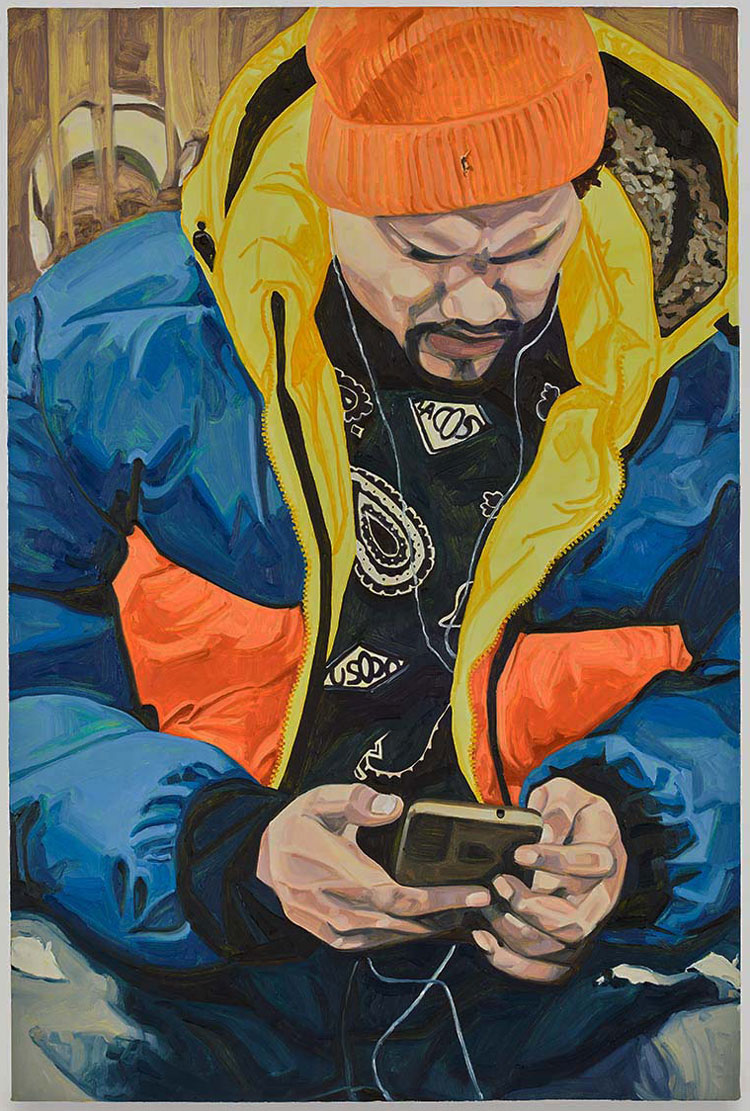

The size of Casteel’s subjects puts them on a level with the viewer; it feels almost as though they are present in our space. That sense of intimacy is further heightened because Casteel invites us into what has been her world over the past couple of years: we meet Noor and Adam, a couple who live near the artist and her husband, her best friend Wayde, and Andres the garage parking attendant. We see people she has observed on the subway, such as a man engulfed in a bright puffy jacket, who is focused on his phone, oblivious to the presence of the artist, playfully painted in behind him, and a little girl with cornrows, equally lost in concentration as she eats a “Happy Meal”, her feet dangling above the train floor. “I just love the freedom she evokes, the Happy Meal, her contentment. But also her independence, the maturity she has to have as she sits on the chair by herself,” said Casteel.

[image3]

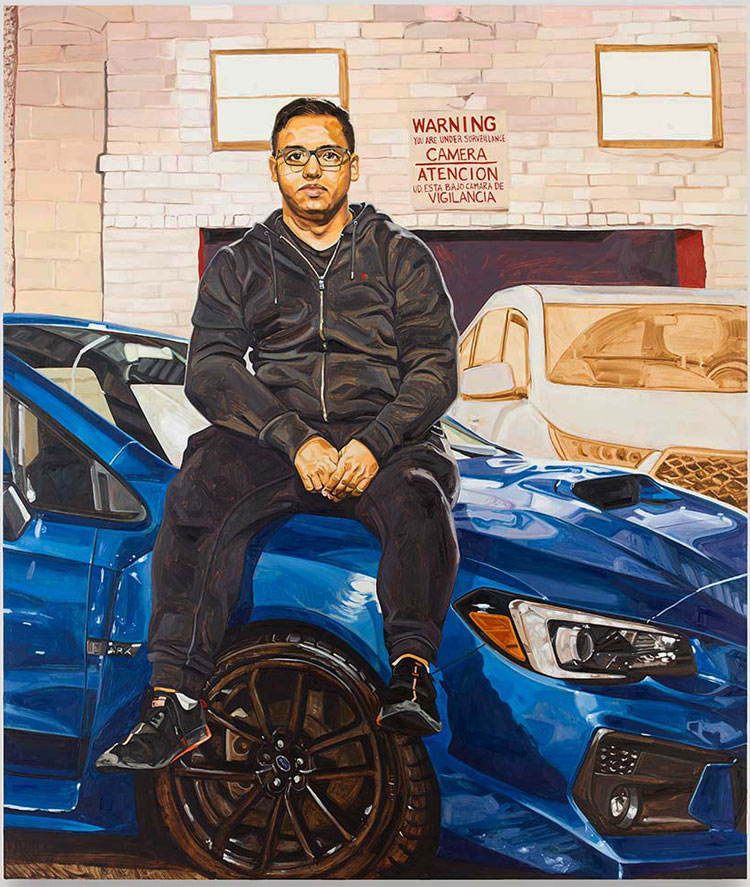

Each painting tells a story, built up through multiple details of the subjects’ environments. Andres sits proudly on an immaculate blue car in his garage; in another canvas, Direct Response, a construction worker in a hi-vis jacket slumbers, exhausted, in his subway seat next to his hard hat and bag.

For Casteel, the transit space is about moments of reflection, her “noticings” of things that feel familiar, such as a posture or expression. They allow an opportunity to investigate the abstraction that exists within these representational forms with a very topographical structure in essence, like the way that the paintings are built and the structures within them and the relationships between line and form, soft and hard.” Casteel is particularly adept at texture; you can almost feel the fur on Wayde’s jacket collar or the hard subway seat beneath the girl in Happy Meal.

[image9]

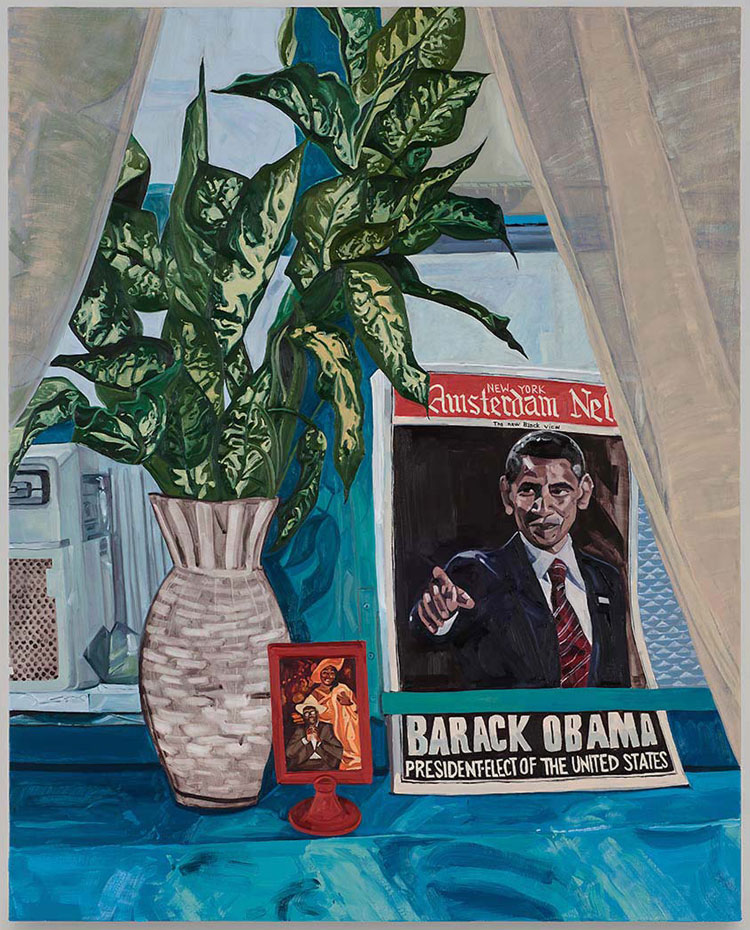

All the paintings here are effectively portraits, even those without sitters. Although ostensibly a painting of an apartment windowsill, The New Black View (Still Life with Yvonne and James) is essentially a portrait of James Boyd, a street vendor now in his 80s, whom Casteel has painted several times. The framed photo on the sill of Boyd with his late wife Yvonne, together with items she would have carefully displayed, such as a large plastic plant and a plastic-covered copy of the magazine Amsterdam Newswith Barack Obama on the front, say much about the things that mattered to Boyd. The painting captures a moment before Boyd’s home was due to be renovated by the city and would lose all Yvonne’s individual touches, Casteel explained, and there is a certain stillness to the work that conveys this sense of loss.

[image8]

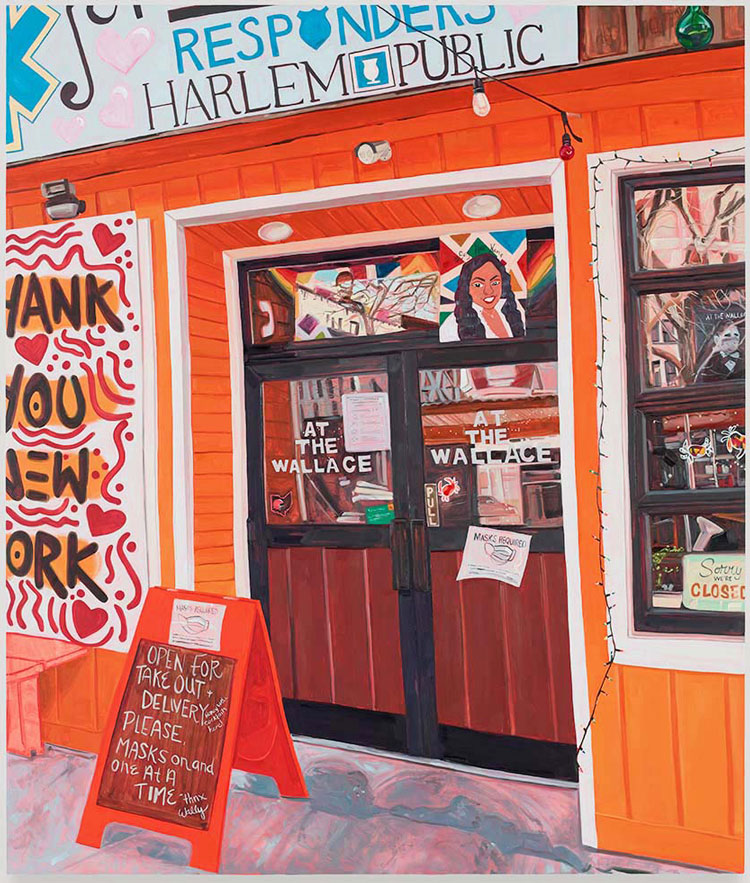

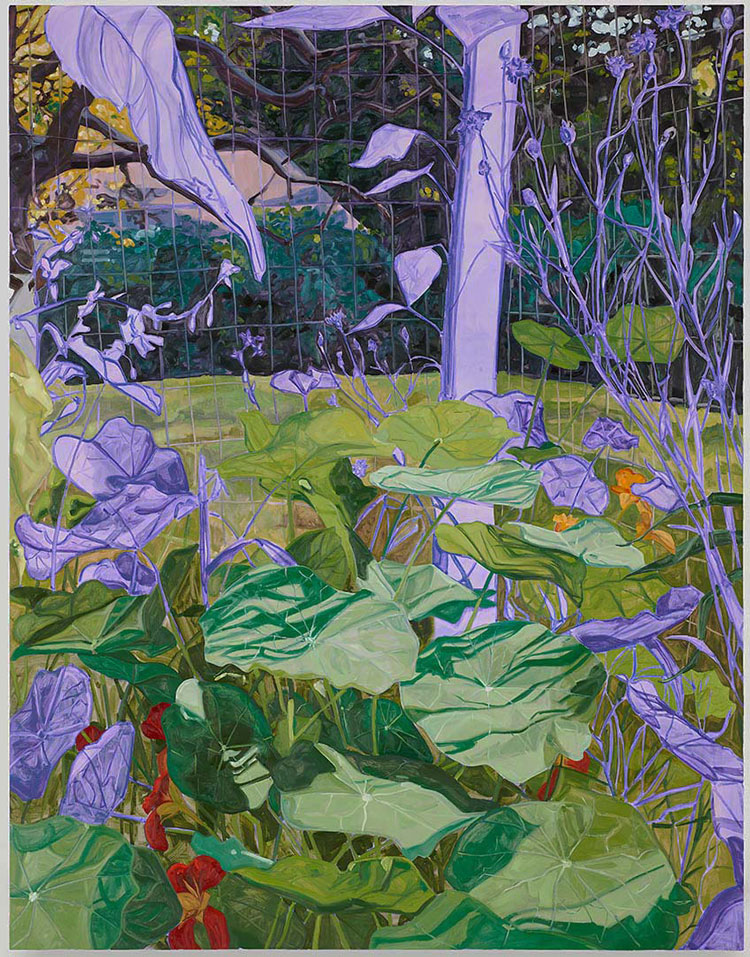

The show also includes portraits of places that hold significance for Casteel, such as her beloved garden and a Harlem cafe called At the Wallace – both of which provided solace during the pandemic. The sympathetic community character of the cafe can be gauged by the signage above its door paying tribute to first responders, artwork with hearts saying “Thank You New York”, a painting in the window of Breonna Taylor, and notices politely asking visitors to wear masks. Nasturtium, which depicts Casteel’s garden, is devoid of any figures and, interestingly, the artist says it is the closest to a self-portrait that she has done. “This is the most connected to my own sense of being and what my journey was this past year,” she said. “I put everything into this garden. I nourished it. I was spending an immense amount of time there and I just felt free and calm in a way that I haven’t for a very long time.”

Exuberantly filling the picture plane, the garden is suffused with a luscious purple that bathes everything in an alluring, ethereal light. Many of Casteel’s canvases have this singular luminosity which comes from her covering them in a single base colour that becomes like an aura – as seen with Direct Response, which seems to emit a dreamlike orange glow from within. In Nasturtium,the dominant purples and greens hold the composition with an energetic intensity. “Oftentimes the colours I choose are more aligned with the image so it’s not as jarring or as present explicitly, it’s more harmonious with the image but I wanted it to feel like it was a base of vibrant saturated playful joy,” said Casteel.

[image7]

These paintings mark time, literally. Casteel’s garden points to the lush fullness of summer. Wayde perches on railings against a backdrop of powdery snow and barren trees. Winter over, we see Noor and Adam sit tranquilly holding hands on a trunk in their garden, the spring light dappled a vivid yellow-green through the leaves, emphasising the gnarled texture of the tree bark.

The compositions are loosely derived from photographs, but details are changed, removed or added to in the course of painting so that the photos serve more as reference material. When she’s painting, Casteel works quickly, in wet-on-wet, that is without waiting for one layer of paint to dry before she applies another. “I like discovering what paint can do when it's wet and colours change and shift and I’m forced to work within a certain confine of time. It allows a certain freshness,” she said. Her practice is set up to prevent herself from overthinking, she added. “If I let my brain dictate too much what it is that I’m seeing and what it is that my subjects need, then I’m not actually capturing them in the way that I think that they deserve.”