Two Temple Place, London

26 January – 22 April 2019

by ANNA McNAY

With the bicentenary of his birth on 8 February this year, there is, deservedly, a renewed interest in the Victorian polymath, John Ruskin: a writer, whose collected publications run to 38 volumes; an art critic; an artist; a teacher; a social commentator; a collector; and, importantly, a supporter of artists. His anniversary is being marked by a plethora of exhibitions around the country, including several at Brantwood (his final home in the Lake District); Ruskin, Turner & the Storm Cloud: Watercolours and Drawings, which is touring from York Art Gallery (29 March – 23 June) to Abbot Hall Art Gallery, in Kendal, on the edge of the Lakes (12 July – 5 October); and John Ruskin: Art & Wonder at the Millennium Gallery, Sheffield (29 May – 15 September). The latter is a further iteration of the exhibition, John Ruskin: The Power of Seeing, currently on display in the neo-gothic mansion, Two Temple Place, on the Embankment, London, which celebrates primarily Ruskin’s intentional legacy, the Guild of St George.

[image3]

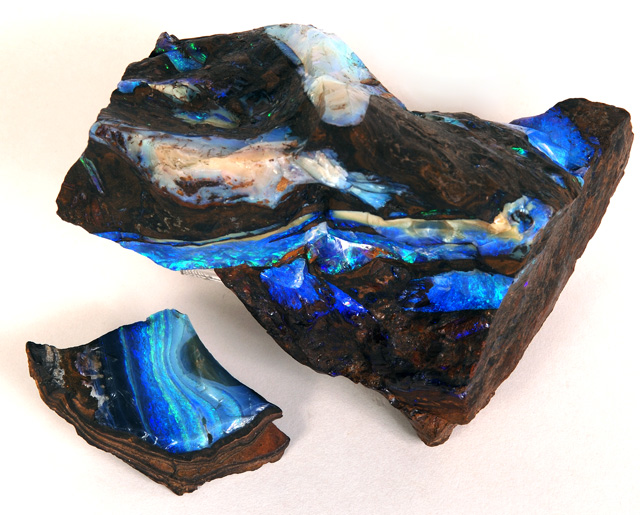

Ruskin established the Guild in 1871 as a society aimed at promoting improved systems of education and agricultural management. In 1875, he opened St George’s Museum in a cottage in Walkley, on the north-east edge of Sheffield (now a suburb of the city), as a venue to showcase the Guild’s collection. Amassed by Ruskin himself, it was what one might call idiosyncratic, ranging from copies of early Renaissance paintings to studies of medieval architecture and decoration, engravings and mezzotints after JMW Turner, coins and medallions, rocks and minerals, and a large library of books and illuminated manuscripts. The location of the museum required visitors to walk up a hill out of town and, in so doing, Ruskin hoped they might breathe in some fresh country air and observe the views back down over the city and the Loxley and Rivelin Valleys. He very much wanted to open visitors’ eyes – not just to the artefacts themselves, but, through these, and through their time out at the museum, to life and nature at large. He held a strong belief that education, beauty and nature should be accessible to all, and key to the collection was the idea that beauty could help people improve their understanding of the world around them. “To see clearly,” he wrote, “is poetry, prophecy, and religion – all in one”. The museum was open seven days a week, until late, so that locals could visit after work. It was staffed by a live-in curator and Ruskin protégé, Henry Swan. Today, the Guild is an educational charity and the collection is now cared for by Museums Sheffield.

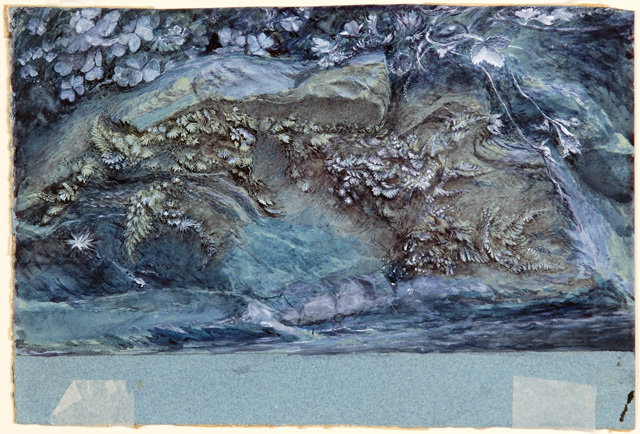

Amply filling the two floors of Two Temple Place, the artworks and objects on show from the collection are accompanied by loans from various other institutions, including the Ashmolean, Tate and the V&A. Upstairs, one room has been laid out to replicate the Walkley museum, with a domestic feel to it, and vitrines containing examples from Ruskin’s collection of rocks and minerals, which, back in the day, “well-behaved”, regular visitors to Walkley were occasionally allowed to handle. As a child, Ruskin dearly longed to become a geologist. His father, however, had other ideas, intending his son to become a bishop.

[image4]

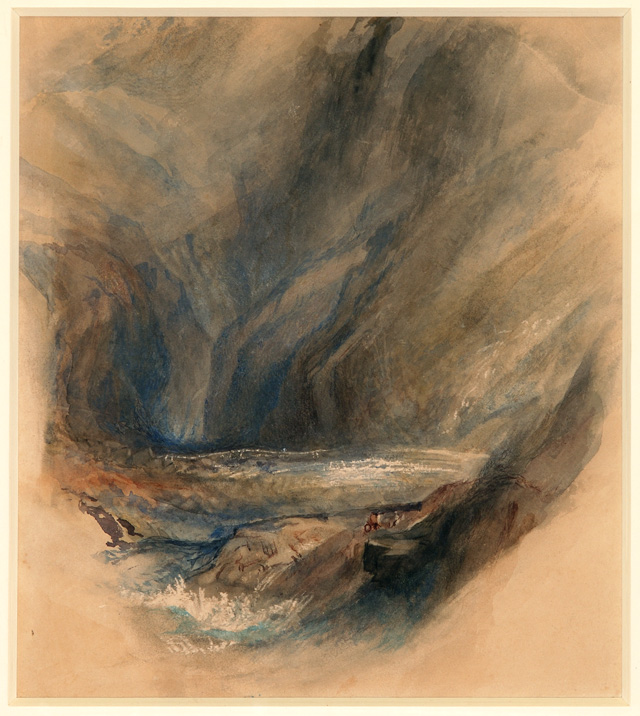

Next door, Octavia Hill’s copy of Giovanni Bellini’s Portrait of Doge Leonardo Loredan (1859) is one of numerous examples of work produced by an amateur artist tutored by Ruskin via correspondence. There are also, of course, works on show by great masters, such as JMW Turner, whom Ruskin regarded as the greatest painter of his age. Ruskin first encountered Turner’s work at the age of 13, when he was given a book-length poem illustrated with his etchings. He went on to write a solid defence of the artist in his critical work, Modern Painters. “Turner perceives at a glance,” he said, “the whole sum of visual truth open to human intelligence”. Ruskin implied that Turner’s success could largely be attributed to his initial documentation of the “clear facts” in pencil. This then allowed him to produce a more enigmatic, emotive response, further capturing and conjuring the atmosphere and personal experience. What Ruskin’s and Turner’s works share – and it is a joy to be able to see them here hanging side by side – is an incredible translucency, making the scenes at once ephemeral, yet exceptionally real; mere suggestions, but, through their subtlety, more solid than anything too finished or too laboured.

Ruskin’s other main love, Venice, is, of course, also omnipresent throughout the exhibition, with numerous sketches and pages of notes, recording feelings and responses as well as facts, for his three-volume work, The Stones of Venice (published from 1851-53). Ruskin spent many months photographing and drawing in minute detail aspects of the buildings that had previously been ignored and that were under threat of restoration. He campaigned vehemently against this work, describing a restored building as merely a corpse, and, by 1880, was successful in stopping the restoration of St Mark’s.

[image6]

Ruskin did not see himself as an artist, but used drawing as a means of connecting with the world. As Slade Professor of Fine Art at the University of Oxford, his lectures comprised far more practical application than artistic practice in and of itself. For example, he believed that the basic “character” of a tree could not be properly expressed until its “minutest extremities” had been drawn and understood. In the 1870s, he worked on what became known as the Grammars, covering the subjects of ornithology, botany and mineralogy. Examples of these – notes and plentiful sketches – are also on display.

Ruskin further wrote of his life “bottling skies” – drawing and writing about clouds and measuring the blueness of the sky with a cyanometer (a card painted with different blue tones). In Modern Painters, he described clouds as God’s “daily handiwork”, created for man’s pleasure. Light in the West, Beauvais (1845) is an enchanting small sketch on blue-grey paper, showing clouds scudding, with white light in bright rays, an absolute embodiment of the wind, and flowing water. Similarly, Cloud Study (date unknown), graphite and ink on white paper, is made up merely of basic cross-hatching with extended flowing lines, but it creates a real sense of breeze, flow and movement. In his latter years, Ruskin began to see the pollution resulting from increasing industrialisation. He noted the changes in the clouds and the colour of the sky. At the time, this was pooh-poohed by scientists – now, of course, we have the benefit of hindsight. His lecture, The Storm-Cloud of the 19th Century, detailed this pollution, but it sadly also mirrored his decline in mental health.

[image8]

A real treat is the vitrine containing Ruskin’s diary from 1835, comprising his incredibly neat handwriting and sketches. As a writer, I always experience an involuntary shudder of pleasure, delight and trespass, when being gifted such a glimpse of the direct outpouring of another writer’s hand. Visually, however, the most beautiful work on show – to my mind – is Vevey, Sunrise (date unknown), which resonates in a glorious, profound blue, with watery mountains rising out of a crystalline lake. It depicts Switzerland, but could equally be the Lake District, or, in fact, the waters of Venice. The translucent layers conjure the effect of seeing overlaid slides, or, perhaps, a daguerreotype. Ruskin captures something essential, something moving, living and breathing in this scene.

Louise Pullen, curator at Museums Sheffield, notes that, in planning their leg of the exhibition, she was “keen to keep reverence for Ruskin as an artist to a minimum”, focusing instead on his desire to bring out the artist in others. To this end, the exhibition is also accompanied by a number of new contemporary commissions, including a variety of curious clay objects by Grizedale Arts; a large-scale drawing of an oak tree by Hannah Downing; and a film by Dan Holdsworth (Acceleration Structures, 2018), which uses 3D modelling and photogrammetry to take the viewer on an impossible but enthralling journey through the layers of three Alpine glaciers above Chamonix. This final piece absolutely encapsulates Ruskin’s desire to see into things so as to fully understand them and then see them as a whole. It brings together science, understanding and sheer beauty. Thus, even if you don’t leave the exhibition primed to pick up your sketchpad and pencil, you will, at the very least, hopefully have been reminded of the primal joy of looking, learning, and envisioning – as well as of the timelessness of Ruskin’s ideas.