by CHRISTIANA SPENS

From her abstract expressionist paintings in the 1970s, evolving into figurative work that confronts and subverts mainstream representations of the female body, Joan Semmel (b1932, New York) has produced a fascinating and defiant body of work over her lifetime. Now 89, her latest paintings continue to chart her self-reflective exploration of existing in a world that fetishises and distorts the female figure. Empowering, celebratory and inspiring, her work shifts the viewpoint and the conversation, speaking for herself and, in doing so, opening up the world for other women and especially artists to take control of their own perspectives, narratives and bodies.

[image2]

With a retrospective, Skin in the Game, at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) until April, which spans 60 years of Semmel’s paintings, and ahead of her presence this month at Frieze Los Angeles with Alexander Gray Associates, she talked to Studio International about her latest work.

Christiana Spens: To depict the ageing female body and one’s own experience and shifting perception of it seems to me the ultimate rebellion in a society obsessed with youth and specific appearances of young female bodies, and also to reveal the perversity of this norm. What are your views on the representation of ageing and older bodies in art today, and has anyone in particular inspired you to focus your attention on these issues and this aspect of your own experience?

Joan Semmel: I never started out with the idea of specialising in ageing bodies or using it as a theme. I merely was using my own body as model over the years and, of course, the usual metamorphosis was taking place. When I was doing the Locker Room Series, there were people of all sizes and shapes as well as age. I was simply not excluding those who did not conform to any preconceived notions of beauty. Of course, I realised that this was untrodden ground and was therefore glad to explore it with a fresh eye. I am not aware of others, except perhaps John Coplans, who worked with photos a little after my early self-images were being shown.

[image3]

CS: Reclaiming the gaze of the female nude and, inherently, its sexuality is still clearly hugely important, despite some social progress and the attention given to more female painters than in the past. How does your work continue to respond to the mainstream media and porn-influenced treatment of the female figure?

JS: When I began to work with representations of the figure, there were not yet the formulations of the critical discourse such as “the male gaze”, but I was, of course, addressing precisely that cultural phenomenon by insisting on and prioritising my own point of view. That aspect of my work is self-evident at this time.

The pervasiveness of exploitative images and narratives of women continues to be instrumental in distorting people’s perceptions and aspirations. By using my own body without adjusting its imperfections to idealise or aestheticise it, I tried to undercut those distortions.

I continue to try to allow my work to respond to my own personal place in time and space and respond accordingly, trusting that the larger cultural issues will also be present in my art as they are in my life. Any art object in the end is about itself, regardless of the motivation or the rationalisation that triggered that response.

[image4]

CS: How have you avoided fetishisation of the female body, and instead found ways to validate the female, embodied experience?

JS: Avoiding fetishisation is a tall order in this environment. The whole genre of the nude in art history and the more modern and contemporary mass media and film industries that have extended the practices by eroticising segments of the body makes it very difficult to do so.

I don’t have a formula that necessarily works. However, I think that a sensitivity to the implications of an image in respect to its emphasis and use is important. I think the full body of my work, as it can be seen at the PAFA retrospective currently on view in Philadelphia shows some of the ways that have worked for me.

[image5]

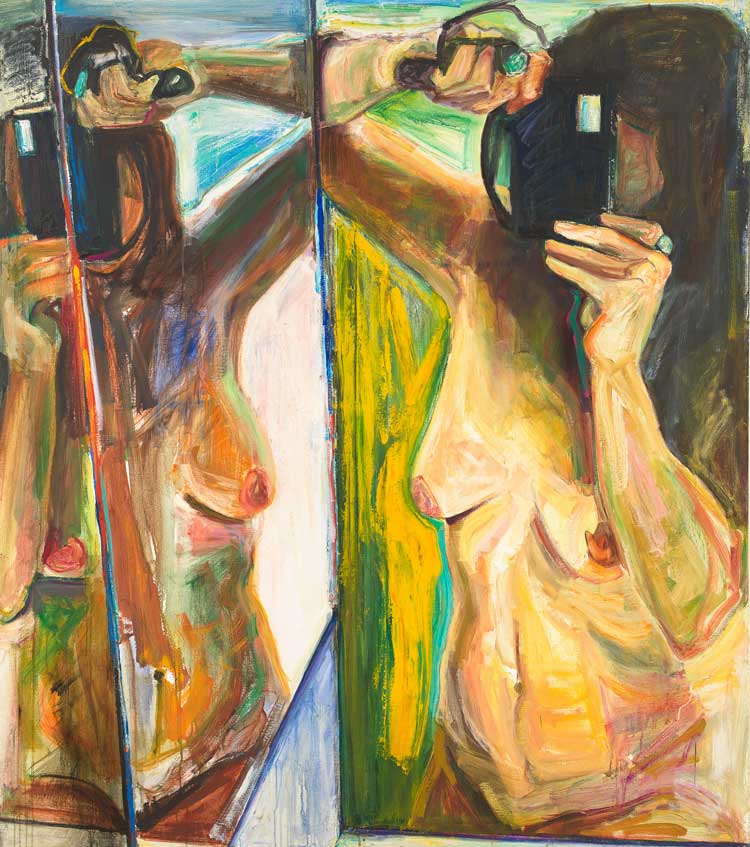

CS: The overlapping figures at times suggest movement and at other times memory, and perhaps overlapping fragmented memory. I also think of a visual conversation between yourself and your body. Could you explain your own ideas behind this overlapping?

JS: The overlapping of bodies does suggest those meanings. When I make the photos from which I work, I usually have several that are almost the same but move slightly in space. When seen together it suggests the movement not only in space but in time, the overlapping brings in memory, the way we can be thinking of something past while doing something present. Film-makers have played with these ideas, but I was interested also in breaking down the static nature of the painted object. The use of overlapping also gives me the possibility of using transparency of paint and the illusion of space created by the layers and not by the rules of perspective. Painting is always for me a conversation between myself and the canvas, you make a mark and it speaks to you. You then respond and make another mark, or erase or modify. It is that process that engages me. The fact that I am working from a representation of my body is not the primary impulse.

[image6]

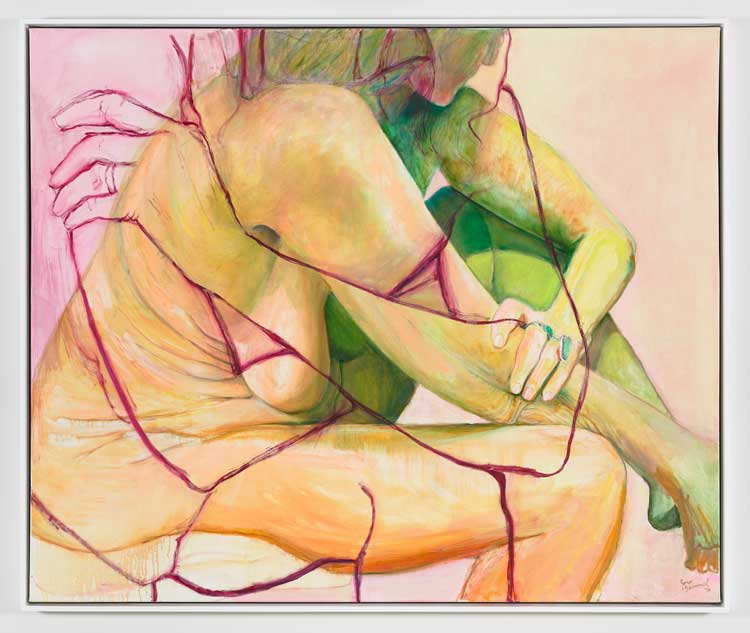

CS: The colours, which are not “realistic”, imply a brightness and almost a transcendence that takes you out of the fully embodied experience, implying an emotional or intellectual flight, or a sensuality beyond the physical. What were your reasons for choosing these colours and for expanding beyond the clearly realistic in this way?

JS: I began as an abstract expressionist and always loved using colour with complete freedom. I did not want to give up that freedom just because I was then returning to representation, so I looked for ways to make the colour function for me spatially rather than locally. The emotional content and connection of the paint and process to the bodily experience connected the colour to the content of the work.

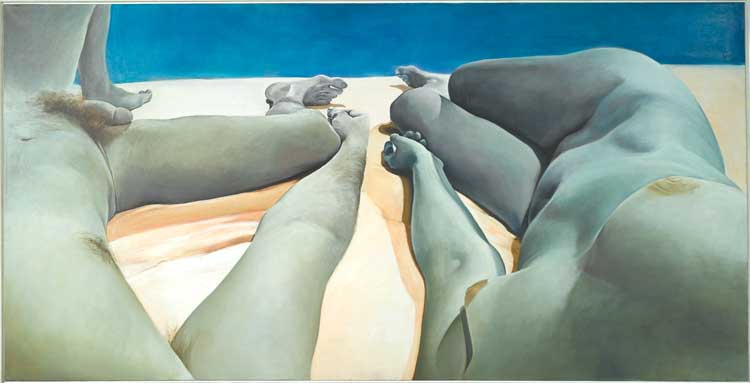

CS: Why have you painted your figures to be larger than life?

JS: I needed the scale to allow for the process. The gesture and speed of the mark is important. I also wanted the figure to achieve monumentality, to be an icon rather than a narrative.

[image7]

CS: Can you tell me a little about your views on the importance of personal assertion and reflection as part of the wider feminist movement, and the necessity of counting the individual within the collective?

JS: I feel that I should not be imposing my views on current generations. I am gratified that my work seems to speak to young people today. On the other hand, I hope that they can frame some of their issues, which can be different from those of my time.

I have always felt that the best work comes from the individual who is strong enough to follow her own inclinations regardless of what is promoted or prohibited. It is necessary for us as feminists to allow for deviance of all kinds. We each need to find our own voice and then work together to affect change.

[image8]

CS: By painting your own body, you have disrupted the boundaries between artist and model, viewer and subject, since you are all of these. In your own life, which memories stand out as inspiring your work across these “roles”, and do you ever feel any conflict or ambivalence about putting yourself as central in your work, on all these levels?

JS: Putting myself central was, and is never, a problem. We were always told that art was about self-expression, so what I took that idea to its logical conclusion. The use of nudity and sexuality were the problem areas around which the element of shame came into play and so I had to deal with how that figured in to how my work was received and how I could deal with it in terms of my own life. I don’t think I ever regretted taking the positions I did.

CS: Which is your favourite among your paintings to be on show at Frieze Los Angeles?

JS: I love all of my children equally, but I usually think the last thing I did is the best. In this case the latest piece of those shown is Spaced Out (2019).

Joan Semmel: Skin in the Game is at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts until 3 April 2022.

[image9]

.jpg)

_1971.jpg)

.jpg)