Joan Mitchell at the Baltimore Museum of Art, March 2022. Photo by Mitro Hood.

Baltimore Museum of Art

6 March – 14 August 2022

by ELIZABETH BUHE

Joan Mitchell at the Baltimore Museum of Art is a symphony, a feast, and a fiercely confident assertion of Mitchell’s tremendous power as an artist. The show contains 54 paintings on canvas, a handful of works on paper, and several sketchbooks. It treats us to the unfolding of a Herculean career of a profoundly dedicated painter whose skill sharpened visibly over time as she grew into the arc of her own gesture. This is the show’s great strength: it allows for the methodical study and subjective experience of the full span of Mitchell’s career. It does so from Lyric, an early abstract canvas of 1951, to Untitled from 1992, the year of her death, with each three- to five-year period in between weighted equally. (Six works on canvas included in the show’s original iteration at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art are excluded here, replaced by drawings.)

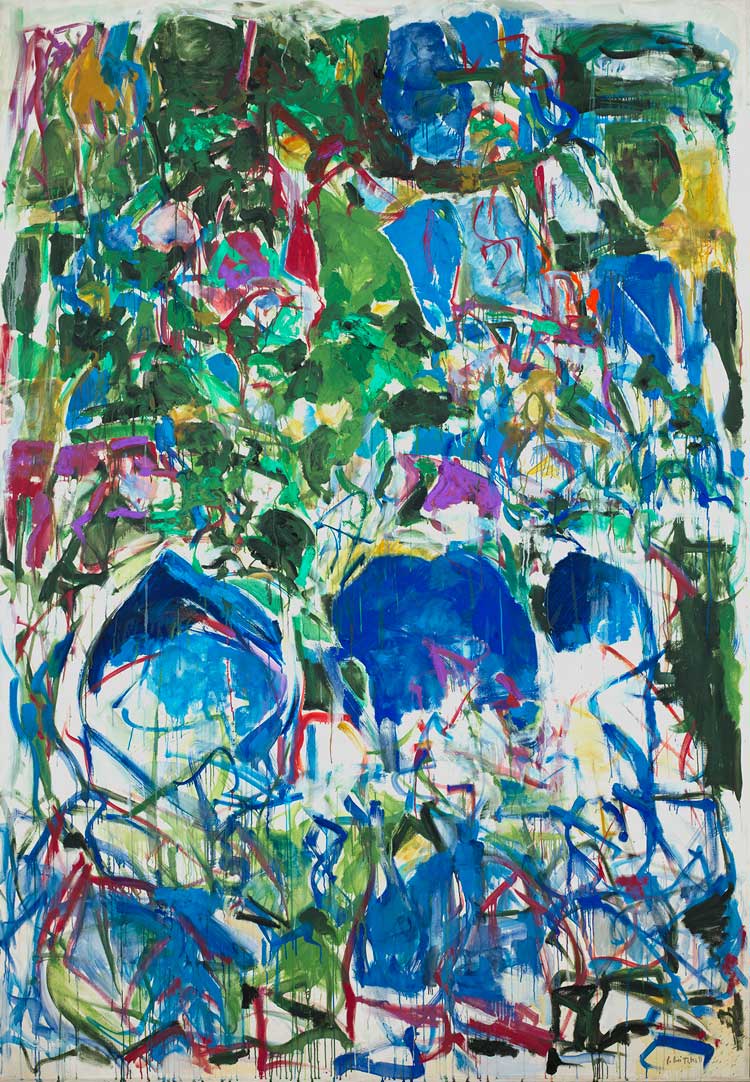

Joan Mitchell. Untitled, 1992. Komal Shah and Gaurav Garg Collection. © Estate of Joan Mitchell.

At Baltimore, the paintings are not always shown to their best effect: the canvases seem cramped, especially at gallery corners and due to floating central walls, the lighting is uneven, and the room containing paintings from 1970-75 is inexplicably out of chronological order. But these are minor objections for a show that permits us to absorb so many Mitchells, particularly since the majority of works hail from private collections and, even more so, because Mitchell’s work demands to be seen in person. Indeed, the show achieves the apparent goal of placing Mitchell within the pantheons of gestural abstraction and American painting through the sheer strength of her painting and the rigour of the curatorial team’s archival work.

Despite consistent showings during her lifetime, Mitchell’s reputation is not as established as the work warrants. She experienced alternating periods of fame and obscurity, due in part to the ebbs and flows of her production occasioned from personal circumstances of travel and loss, as well as to artworld misogyny, which the curators name outright. After participating in significant group exhibitions in the 1950s, such as Leo Castelli’s 9th Street show and the Jewish Museum’s Second Generation exhibition, and with sustained support from her European and New York gallerists throughout the 1960s, Mitchell earned her first major solo museum showing in 1972 in Syracuse, New York. This was followed by solo exhibitions at the Whitney organised by Marcia Tucker in 1974; in Paris, in 1982; and Ithaca, New York, in 1988.

Joan Mitchell. My Landscape II, 1967. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. David K. Anderson, Martha Jackson Memorial Collection © Estate of Joan Mitchell.

The most recent comprehensive presentation was again at the Whitney, in 2002. Therefore, this is the first opportunity for people of my generation to truly know her work. Mitchell, born in 1925, was 47 years old for the Syracuse show; by comparison Helen Frankenthaler was 32 for her first major museum show, while Lee Krasner was 57. This kind of historical context is largely absent from the show, which smartly limits itself to three cases of archival letters, poems and photographs. But it undergirds the catalogue narrative, which largely sticks to fact over interpretation. Individual chapters are authored by Katy Siegel or Sarah Roberts, the show’s co-curators, with focused thematic or single-work essays by other scholars; particularly notable is Jenni Quilter’s essay on lyric painting and lyric poetry. The book is a significant brick in the foundation of scholarship now emerging on Mitchell from which future writers will build.

Joan Mitchell. Hudson River Day Line, 1955. Oil on canvas, 79 × 83 in (200.7 × 210.8 cm). Collection of the McNay Art Museum, Museum purchase with funds from the Tobin Foundation.

In the first gallery, we see Mitchell move quickly from the fractured all-over cubist space of two late-1940s representational canvases to the abstracted view filtered through her personal perceptual lens, deployed as hazy vistas awash with non-local colour set down in scratchy, frenetic marks often organised along roughly horizontal or diagonal axes. These works read not as representations of places but as evocations of the embodied memory or affect of a situation, and as such are at one or more removes from observed reality. Mitchell called this “feeling”, as Roberts explains in the catalogue, “sensory realities and her memories of them”. Exemplifying the ontological subjectivity of this premise, the riot of squiggled marks in Hudson River Day Line (1955) conjured for me the muffled sound of a rushing river.

Joan Mitchell. City Landscape, 1955. The Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Society for Contemporary American Art, 1958.193. © Estate of Joan Mitchell.

Given the importance of subjective experience over objective referent as an interpretative rubric over Mitchell’s career, and its implications for the definition of abstraction in her case, it seems misleading that the wall text for the first abstract painting we encounter, City Landscape (1955), reproduces a photograph of a view of Lake Michigan from Mitchell’s childhood residence in Chicago, as if setting us on a journey to seek out or imagine such real-world locales in her work. In a catalogue text on The Bridge (1956), which is also on view in this gallery and is Mitchell’s first known diptych, Marin Sarvé-Tarr offers more open-ended terms, writing that the painting’s strong architectural armature and dry, sweeping red, blue and olive marks encompass “a body of transatlantic travels and experiences” and “captur[e] the importance of mobility and memory in Mitchell’s abstraction”.

Joan Mitchell. The Bridge, 1956. Oil on canvas, 46 × 70 1/4 in (116.8 × 178.4 cm). Private Collection.

Another exemplary canvas in this room, Untitled (1953-54), shows Mitchell working out problems in paint by emptying out colour, as did early analytic cubism, to focus on mark-making. This painting’s short impastoed or drippy marks in fawn-grey and blue-tinged white hatch together in a circular form and put Mitchell in dialogue with Jean Dubuffet’s textured matière or Sam Francis’s contemporaneous white scrims. In retrospect, Untitled appears a brave experiment in a new abstract idiom for an artist whose career was, at this point, by no means assured.

Joan Mitchell. Water Gate, 1960. Oil on canvas, 86 x 84 in. Private Collection, courtesy of McClain Gallery.

By the time Mitchell definitively moved to Paris in 1959 after years travelling back and forth from New York, she selected and emphasised bold colours within a single canvas, like the shock of nearly fluorescent purple in Untitled (c1961), or the gallant central sidelong swipe of royal blue in Water Gate (1960). Her forms condensed and began to stand alone, shrinking from the edges. Still, she responded to a canvas’s external limits with practiced intuition: at the lower bound of Water Gate, a white mark in the shape of a cursive J crooks downward after a rightward sweep, then swings back to the left. About halfway, the white becomes black, perhaps the rotation of a brush loaded with the two colours, or simply the addition of a second mark, a characteristic technique of tracing and extending that painter David Reed refers to in the catalogue as “doubling”. It is extraordinary to follow in this exhibition the flicks of Mitchell’s wrist and elongating reach of her arm over time, to see her searching, testing, learning and changing. As a painter with whom I viewed the show noted, even when Mitchell did not land a mark that she set out to make, she pivoted it to her advantage into something else, like a well-practised athlete. The evidently confident stretch of Mitchell’s brushwork culminated, for me, in a painting made in dialogue with Mitchell’s friend, the composer Gisèle Barreau: the wall-sized, magisterial diptych Two Pianos (1980), in which the up-down strokes in lavender near the right panel’s top evidence an artist in absolute command of her materials.

Moving through the galleries, it becomes clear that Mitchell was methodically building systems of colour, structure and gesture. In Russian Easter (1967), Mitchell achieved sparkling chromatic texture by deftly placing prickly blooming passages in deep red, bright white, forest green and mustard brown alongside other colours, seeking the different tonal effects occasioned by adjacency. In this canvas, we also see Mitchell systematically couple colours; forest green, for instance, often tops lapis blue. Like many of Mitchell’s works, Russian Easter is imperfectly symmetrical or chiral, a term that implicates the body via its prime example of a person’s two hands. Mitchell’s juxtaposition of demarcated passages means that the paintings elicit a perceptual process whereby we carry an optical impression of one thing (or painted passage) into the next, making the paintings seem self-conscious interrogations of perception itself.

Joan Mitchell. Ode to Joy (A Poem by Frank O’Hara), 1970-1971. Oil on canvas, 110 1/2 × 197 1/4 in (280.7 × 501 cm). University at Buffalo Art Galleries: Gift of Rebecca Anderson, 1988. Photo by Mitro Hood.

Mitchell further sharpened this abutment of discrete yet interlocked forms in the early 1970s, when rectangular offset blocks of colour swell to a canvas’s edges. I found Ode to Joy (A Poem by Frank O’Hara) (1970-71) particularly affecting; for several seconds, it became dimensional, iridescent, its patchy passages lifting from the canvas, hovering. In this moment, I stopped registering ambient noise. If true that Mitchell was a colour-grapheme synesthete (as am I) as the catalogue suggests, then sensory crossings would be normalised for her. This could sanction colour-note associations, too, rendering Ode to Joy akin to a score. Synaesthesia returns us to the unverifiable realm of the subjective, and certainly Mitchell’s works are unusual in their capacity to elicit embodied, sensory, or affective response. On this point, the catalogue offers useful vocabularies: for Mara Hoberman, the artist “simulates (as opposed to merely illustrates) an evanescent life force”; for Richard Shiff, her paint colours are highly specific and eschew the generalising effect of words as signs; and for Roberts the early 1960s work is less connected to memories and the external landscape but rather displays “her sensory understanding of, and almost physical identification with, the material qualities of paint”. All this goes far in establishing a specific lexicon rooted in close-looking for the description and interpretation of her work that the Mitchell literature has largely lacked.

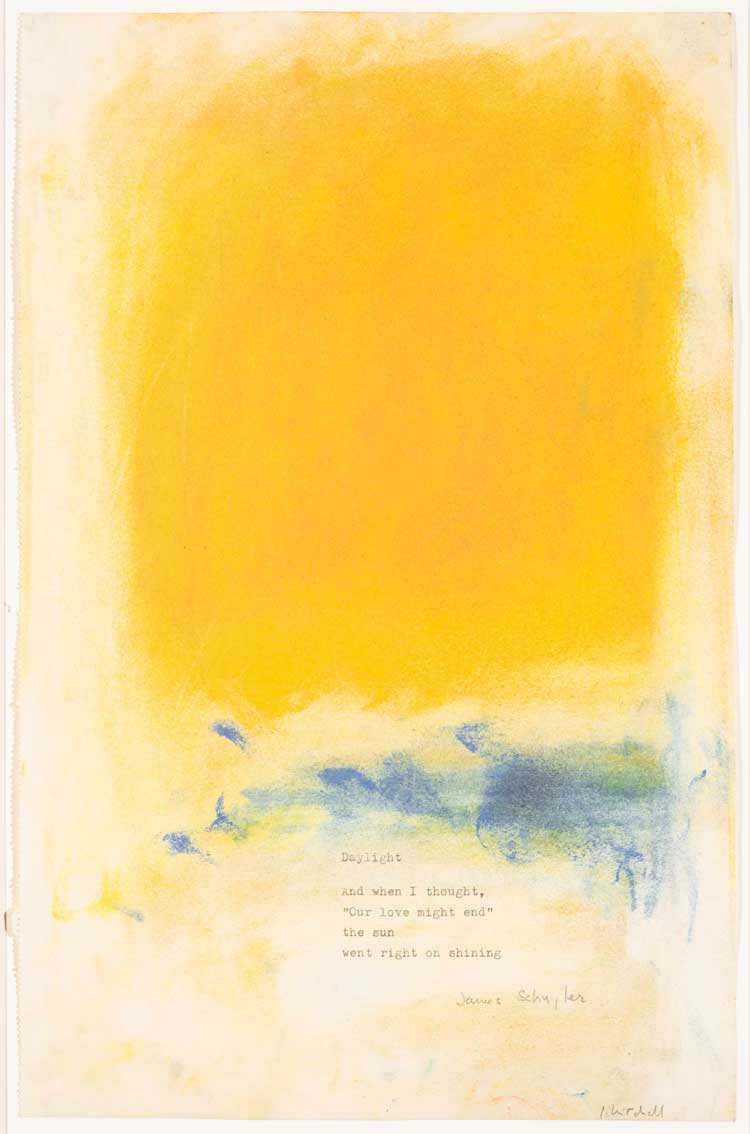

Joan Mitchell. Daylight, c1975. Collection of Nathan Kernan. © Estate of Joan Mitchell.

There are other places where work remains to be done. A catalogue raisonné is underway, which will address straightforward yet complex questions that would have been welcome on gallery labels, such as where each canvas was painted. Curatorial decisions to prioritise chronologies of making and archival evidence (inclusive of conservation research) mean that the exhibition would have benefited from a critical interrogation of key terms, such as transatlantic, landscape, abstraction, perception, “second generation”, and horizontal/vertical that concern hierarchy, power, priority, colonialism, and the subjective nature of embodiment, all of which have been deeply considered in critical theory and, by extension, art history. Doing so would have introduced an anachronism antithetical to the exhibition’s methodology, but is nonetheless vital for the writing of an inclusive art history. The straight-shooting Mitchell probably would not have liked it either, but it is, in any case, another facet of the work to be done – “working, working”, that constant through line in her own articulations. “I’m painting my ass off …”, or, when it didn’t feel so easy: “Oh merde. Anyway, I’m trying.”