Pallant House Gallery, Chichester

2 November 2019 – 23 February 2020

by NICOLA HOMER

Light and colour play across a French landscape, an image of a dancer captures a sense of freedom, an abstract composition is cast in shadow, and a self-portrait evokes a Grecian statue. This modernist author gives the impression of a sense of humour and a knowing look, but she is not widely known. Like many female artists, Jessica Dismorr (1885-1939) has largely been written out of the male-dominated narrative of art history. A contributory factor was her tragic death just before the second world war. After that, her work was put into storage, and there was little energy for a retrospective. Now, 80 years later, the Pallant House Gallery, which specialises in modern British art from 1900 to the present day, is holding the first museum exhibition to focus on the artist: Radical Women: Jessica Dismorr and her Contemporaries. While the museum has opened this exhibition, a paperback that includes some of her outstanding poetry in London Notes (1915), The Penguin Book of the Prose Poem, has been published. This fittingly suggests the Horatian maxim of Ut picture poesis, the notion of the sister arts.

[image8]

While sisterhood is part of the exhibition, which explores the friendships among the artist and her contemporaries, such as Helen Saunders, the guiding spine is the presence of Dismorr. Organised in three rooms, where sightlines connect early and late works, the show traces Dismorr’s journey as she progresses through avant-garde movements, and key moments of modernism, from rhythm to vorticism to postwar figuration and 1930s abstraction. The exhibition situates her work in relation to the times in which she lived, framed by issues of two world wars, the theme of women’s roles and the radical politics of the early 20th century. Dismorr and Saunders were signatories of the manifesto of vorticism, a literary and visual arts movement, founded by Wyndham Lewis and Ezra Pound, drawing connections between art and industrialisation. Like contemporaries featured in the show, such as Paule Vézelay, Dismorr studied at the Slade School of Fine Art and then arrived in Paris. There she met Scottish colourist JD Fergusson, before joining the rhythm group of Anglo-American fauves, to which he belonged, along with SJ Peploe and Anne Estelle Rice. The group was notable for its democratic impulse and significant involvement of female artists.

[image7]

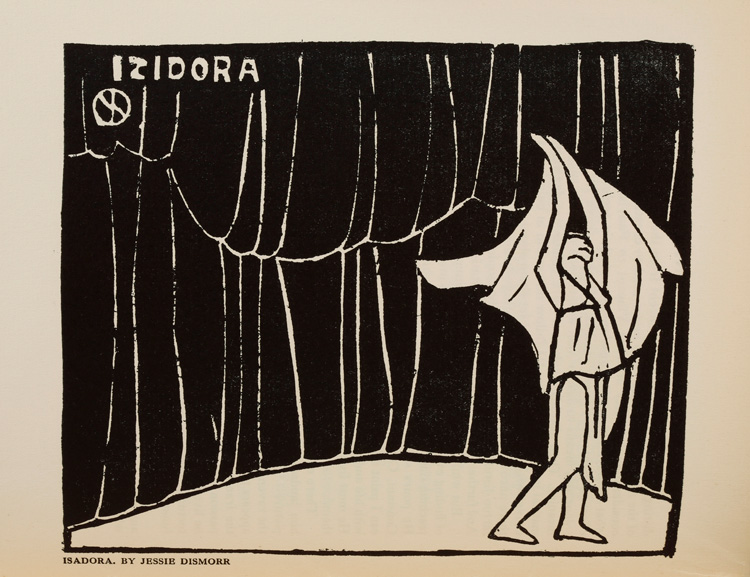

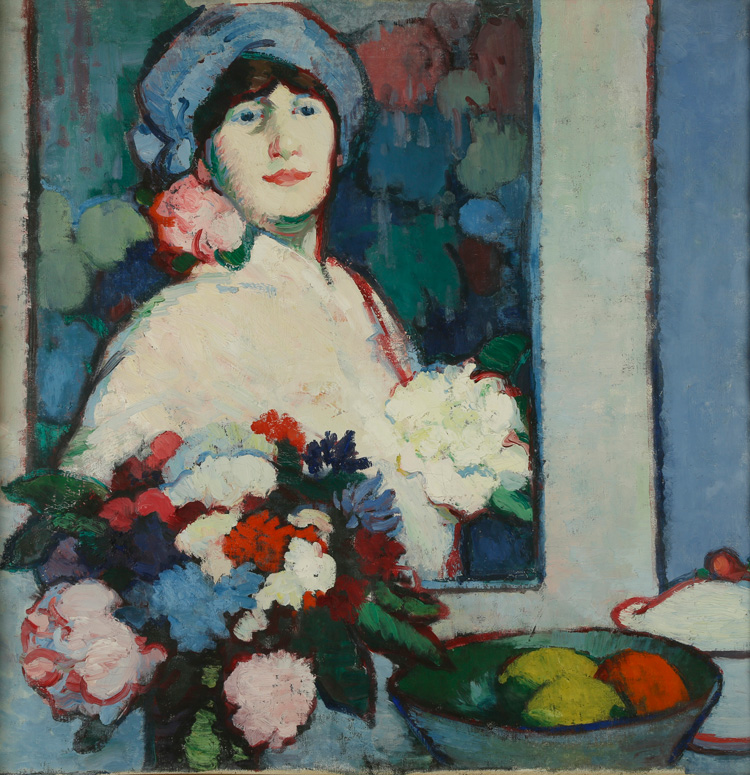

At the beginning you can see an image of Dismorr’s Izidora (1911), from a journal published under the auspices of the literary magazine Rhythm and edited by the short-story writer Katherine Mansfield and her partner, the literary critic John Middleton Murry. A self-portrait by Rice channels the spontaneous colour of Henri Matisse’s fauvism in the shape of Henri Bergson’s philosophy with a vibrant style, illustrating why she was recognised by contemporary critics as equal in standing to Fergusson. Alongside Dismorr, Rice participated in the only exhibition of the rhythm group at the Stafford Gallery, London. J Taylor wrote a review in the Studio, describing it as “very effective” and representing the “English wing of the Post-Impressionist School”. Standing tall is an elegant figure by a piano in a portrait by rhythm artist Ethel Wright. This pictures a radical suffragette, Una Dugdale Duval, who was a campaigner for Christabel Pankhurst, one of the leaders of the women’s suffrage movement in Britain. Duval refused to use the word “obey” in her marriage vows and published a polemical pamphlet on the topic. Evidence of her importance emerges in the vorticists’ journal Blast, listing the suffragette as one of the people they considered blessed. An activist position is seen in Saunders’s Untitled Drawing (c1913), which art historian Lisa Tickner has noted is “the closest to a feminist painting to be made by a member of the avant garde before the war”.1

[image5]

The curator of Radical Women, Alicia Foster, says: “At the moment at which rhythm was at its most powerful, this painting was at the centre of that exhibition. We thought that was fascinating in terms of what Dismorr’s relationship was with politics and modernism, in that all the choices she made after that seemed to also have this engagement with what was happening with the politics of the time.”

[image11]

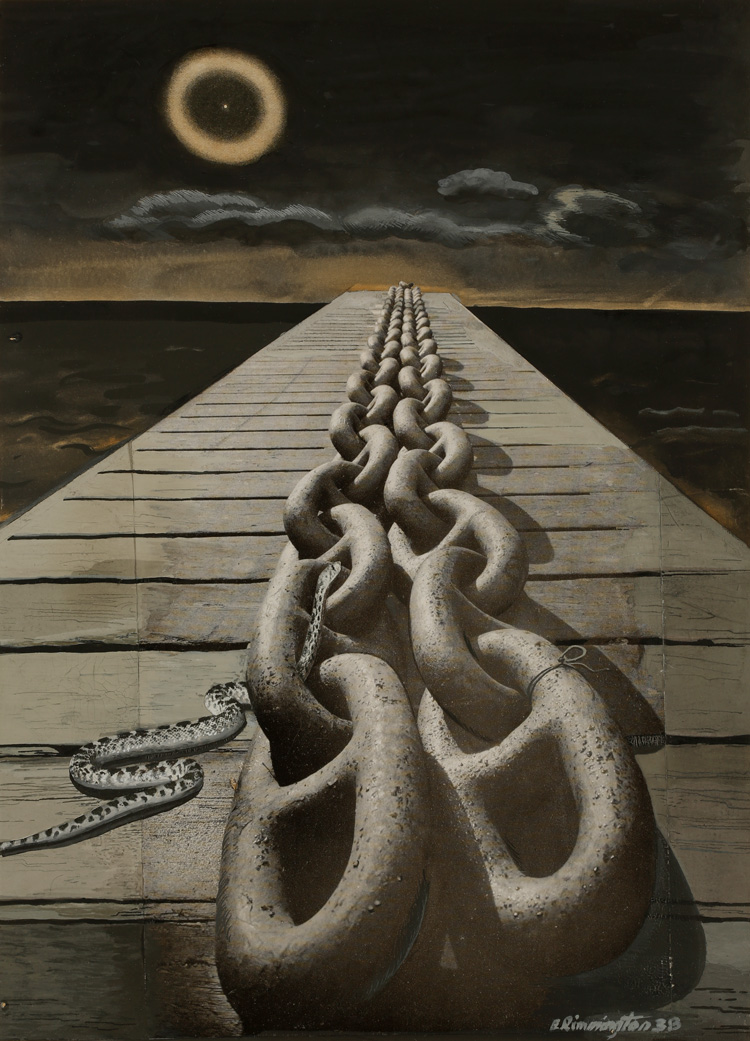

The parallel strands of modernism and politics weaving the exhibition together connect with the fractured times and political turmoil of today. Interestingly, the last UK general election to be held in December was in 1923. A comparable time of political polarisation in the country emerged before the first world war, for instance in the January 1910 election. The war brought chaos: Dismorr's experience of being a war nurse was followed by a breakdown. Yet she was encouraged to work by Lewis, in a letter dated October 1920. After engaging with abstraction in the vorticist movement, Dismorr returned to figuration in the years after the war, like many leading modernist artists, as a “call to order” gripped the avant garde. Dismorr moved towards a sense of cohesion as she made work about everyday life. Interior (1930) captures the family life of an ancient art expert, showing playful shifts of scale and psychological insights, which appear in Mansfield’s short stories. The literary theme continues with a reading of Dismorr’s funny and free-spirited prose-poem, June Night (1915), which you can listen to through headphones. This gives recognition to her fierce talent as a poet, and her witty sense of humour, which offers a touch of lightness to the dark times of the exhibition.

[image2]

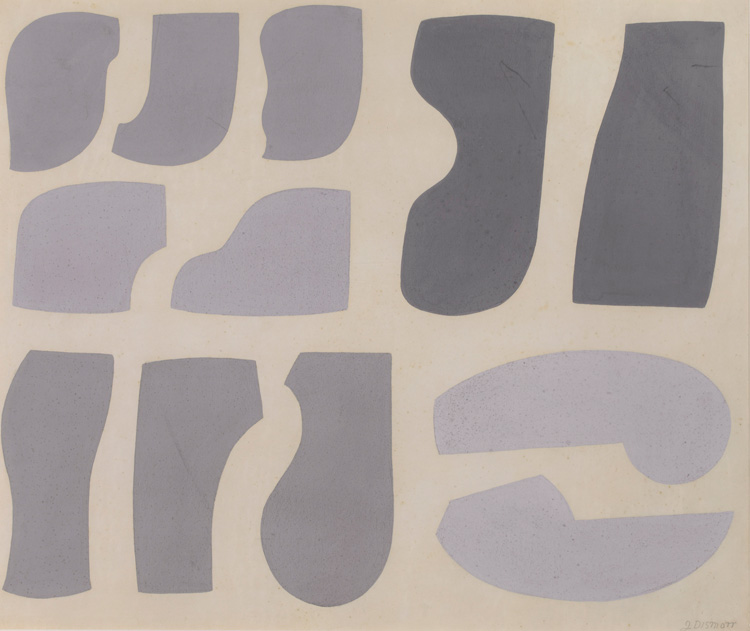

Towards the end of her life, Dismorr allied herself with the Artists International Association, whose pioneers included Betty Rea, with whom she showed work at the anti-fascist exhibition Die Olympiade onder Dictatuur, in Amsterdam, in 1936. In her visual art, she returned to a calm, beautiful and austere kind of abstraction, which embodied an internationalist spirit, in such a way that it remains prescient today. Foster says: “If you see that abstraction in the context of what is happening in culture in the 1930s, you have the rise of Soviet realism, you have Hitler’s promotion of figuration and queasily sentimental and heroic cod classicism. Then you’ve got Dismorr, who is creating art that allies itself very powerfully with internationalism, with progressive politics, with the idea that art crosses nations, that it doesn’t have a nationalist message and a nationalist agenda. So, this has been one of the excitements of the show, that through the research, this has come to light.”

Reference

1. See Radical Women: Jessica Dismorr and her Contemporaries by Alicia Foster, published by Lund Humphries, 2019, page 34.

.jpg)