Guggenheim Bilbao

22 March – 9 September 2019

by VERONICA SIMPSON

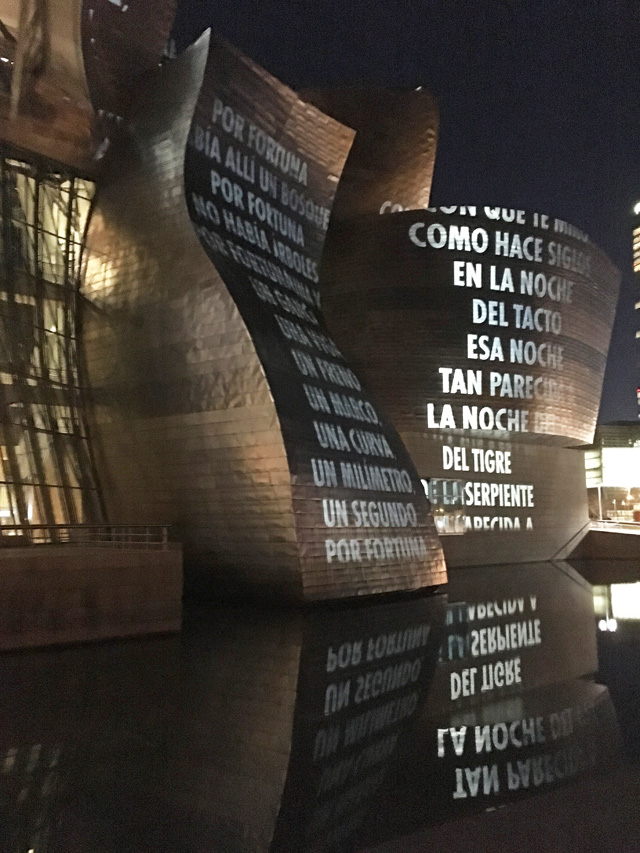

For an activist artist, there can be few more exciting prospects than broadcasting your message across an entire building. Not that Jenny Holzer hasn’t done this before: she has been throwing light and poetry on to buildings since 1991; more than 50 buildings in cities around the globe, to date. But if you are going to pick a building as a canvas, there are few more seductive than the Guggenheim Bilbao. Just picture it: one of the most iconic cultural landmarks in the world with the words of the wounded and the dying scrolling up its voluptuous contours.

[image2]

Because, of course, that is what Holzer has chosen for her text: there is poetry as well as witness accounts from refugees from the world’s war zones caressing the titanium tiles: each word shining, silvery white against the bronze evening tones of the Guggenheim. Not that anyone is paying attention on the preliminary test night when I am privileged with a preview: for the most part, the riverside promenade is full of Bilbao folks going about their usual evening business – walking their dogs, jogging, having a quick smoke, while words of poetry and pain slide slowly, meditatively up the sides of the Guggenheim. The poems are needed along with these witness accounts of death, devastation and destruction, says Holzer, to “offer solace, tenderness”, a balance between hideous truths and truths that are “sustaining”. “I wouldn’t want to have only love or only war,” she tells the assembled crowd at the following morning’s press conference.

At a time when the art world is finally, fully, celebrating the female talent that has been operating – usually below the radar – for the past few decades, the Guggenheim Bilbao can comfort itself with the fact that it “got” Holzer early: she created one of the inaugural pieces for the museum’s opening in 1997; the nine LED columns are still there, still articulating the testimonials of those affected in some way by Aids up the 12-metre light work, in English, Spanish and Basque (Installation for Bilbao, 1997).

[image14]

But this is the first time that so many elements of the words and worlds that Holzer has broadcast - both borrowed and created - over 40 years as an artist activist have been assembled as a full retrospective.

There are representations of pretty much all her different moods and movements here, from printed slogans on T-shirts and condom-wrappers to LED and kinetic sculptures. There are, however, new kinetic works and paintings to enrich the mix, as well as a whole gallery given over to those fellow artists who have provoked and moved her over the decades; her “Inspiration Room”.

What Holzer (b1950, Ohio) offered as one of a band of protest/activist artists, operating out of squatted lofts in 1970s New York, is a sense of closeness to the street. She made work that was irreverent, improvised, extemporary, angry: her message and her medium (posters) designed for mass exposure and ease of reproduction (in the age before Twitter) rather than self-aggrandisement. It was honesty without self-regard: the point of her works was not that she had made them, but that they said something that needed to be expressed, exposing something grimy and nasty (whether racist or misogynist attitudes or just generally brutish behaviour) to prod and poke at the prevailing veneer of cultural complacency and rampant consumerism.

[image8]

So it is fitting that the exhibition opens with a whole room pasted in her Inflammatory Essays series. The Inflammatory Essays (1979-82) are still powerful – channelling extremist attitudes in multiple colours. Distilling the sentiments presented by manifestos, political philosophies and radical philosophical books, she pasted these 100-word diatribes all over the streets of New York. They seem weirdly prescient now, in the age of Twitter. They still have weight, but it is a different kind of weight. If anything, contemporary context enriches it. When the words have permanence, when they stay on the wall in front of you rather than vanish in the flow of an ever-renewing verbal torrent, you really weigh and consider: “What kind of person would say that?”

[image15]

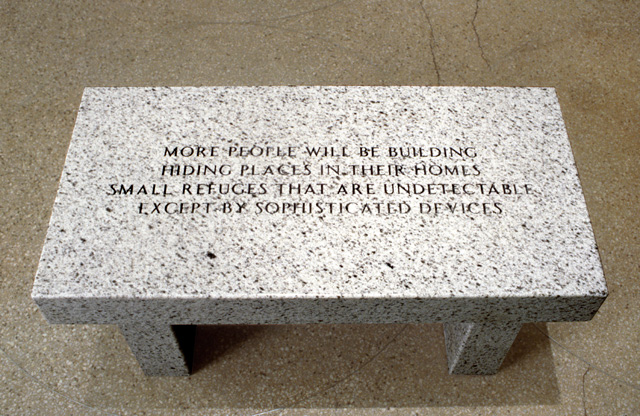

Her Truisms (1977-79) began as an art-school project, gathering nearly 300 pithy one-liners, whether commonplace sayings, cliches and maxims, or condensed philosophical treatises, and printing them cheaply on to posters. Her trick was to co-opt the graphic, headline stylings of contemporary advertising and broadsheet newspapers; capitalised, shouty, emphatic. She went on to print these Truisms on condoms, disposable cups, T-shirts, babygrows, bracelets and silver spoons (presented further on in this exhibition within a biographical corridor, Didaktika), before discovering that these worked just as well – if not better – on slim, LED signs, of the kind you can still find above every corner shop. There are a few of the latter in the exhibition, but more of her later, Laments series (1989). For this she co-opted the material and engraved graphic treatment of the memorial to bear witness to those who were dying of Aids due to prejudice, ignorance and “bad politics”, as she said at the time: the 13 texts she used convey the last thoughts of 13 real individuals, 10 adults, two children and an infant, whose deaths were both unnecessary and preventable.

[image10]

In this gallery we also have two stone sarcophagi, one made from red Ankara marble and the other from Nubian black granite. There is a third sarcophagus made from Breccia Medicea marble that features lines from the Polish author Anna Świrszczyńska’s poem Still Life, documenting the horrors of war. (Świrszczyńska served as a volunteer nurse during the second world war.) Holzer has said: “I appreciate and depend on the ephemeral and disembodied – and on solid rocks. I arrived at stone as a material when I started to do gallery shows. I didn’t want people to have to stand to read my texts on electronic signs. I wanted people to be comfortable, and to take time to look. So I thought to provide benches, and it came to me that I could put writing on the seating, and the benches should be stone … When words are carved in stone, they can be touched, they can be read with the hand; they might be perceived differently than when on the page.”

[image3]

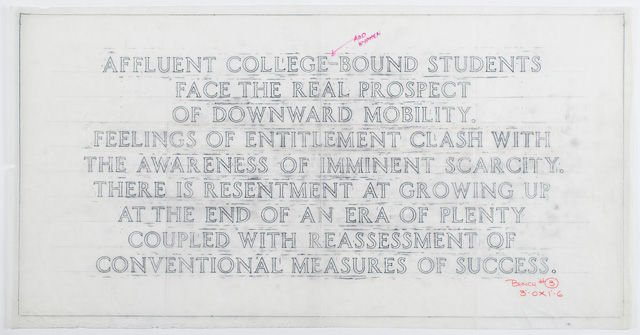

There are more benches in the next gallery, as well as drawings she made on tracing paper to prepare the lettering for the benches, before the process became digitised. These flimsy, ghostly records of her process are mixed in with hand-painted metal and electronic signs, including texts from her Living series (1980-82), which adopts a practical, journalistic tone, and her Survival series (1983-85), which questions the individual’s response to the prevailing political, social, psychological and personal issues of the day; one of her most famous slogans is: “Protect Me from What I Want.”

The third gallery in this opening sequence – the seeming end point through the previous two large gallery’s open doorways – provides a marked shift in tone. Set in semi-darkness, four benches and sarcophagi are placed around the edges of the room and spotlit. A further grouping of seemingly broken or ruined marble benches is placed in a circle at the centre of the room, and around their circumference a kinetic work rotates, menacingly, swinging from a robotic assembly that hangs from the ceiling: There Was a War (2018), is a four-sided vertical LED sign, for which Holzer pieces together elements from 131 eyewitness accounts from Syrian refugees, collected between 2011 and 2016 by Human Rights Watch and Save the Children. As the work moves, towards and away from the viewer, the narrative becomes a physical presence as well as a verbal one.

[image6]

With these LED works, I am struck by how effective the slow pacing of the words is. I like the fact that you read them silently to yourself rather than hear anyone say them aloud. It means that they take up space in your head in a way that a page of text wouldn’t. You can’t skip ahead. You can’t skim.

To the right of this gallery – and again in darkness – is one new kinetic work – I Woke Up Naked (2018), a large metal LED sign swinging violently, albeit slowly, on what looks like a zip wire, from one end of the room to the other. Its subject is domestic violence against women and, for this commission, Holzer gathered testimony from international aid workers as well as records of abuses gathered by local social services workers in the Basque region. I find myself wondering about the purpose of the zip wire. Then it dawns on me: the motion is like the slap of a hand, the whack of a body against a wall.

[image7]

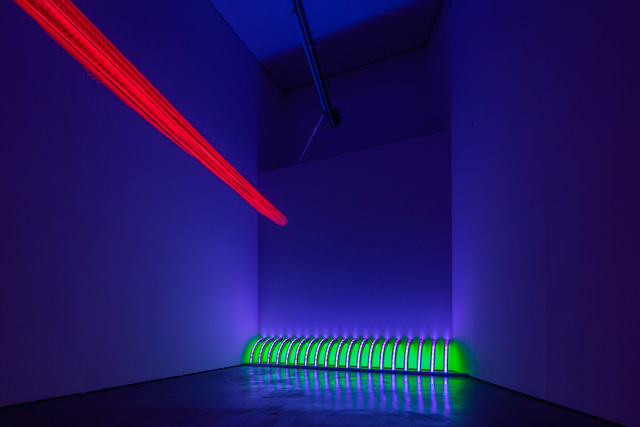

At the far end is Purple (2008), a 19-element array of curved LED signs intended to evoke human ribs, which also documents abuse of women, but this time gathering perspectives of perpetrators, victims and observers of violent sexual encounters from the war in the former Yugoslavia.

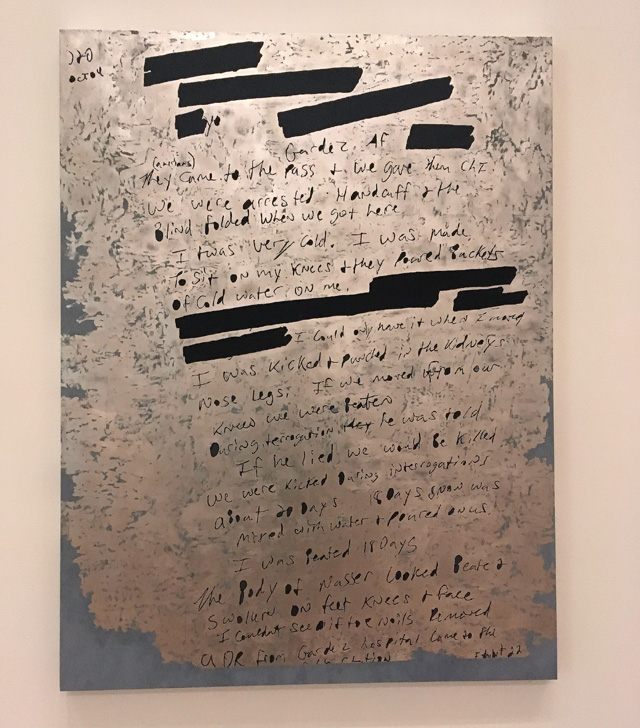

After choosing to immerse herself in the horrors of the world, it is perhaps not surprising that Holzer has abstracted content to the point of beauty in a new sequence of paintings and watercolours. Both series take as their inspiration the many redacted government documents she has been unearthing since the early 2000s, initially investigating Bush-era material about the US military invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, but then widening her search to FBI documents about terrorist threats and cyber intelligence. While the watercolours offer segments of documents stained and dribbled with dense, inky streaks, the paintings transform the material into something remarkable: reminiscent of works by Agnes Martin, Ad Reinhardt and even Kazimir Malevich, these semi-abstract, colour-block paintings are stunning.

[image16]

They take the redacted documents as a starting point, but convert them into pattern: there is a compelling, obliterating rhythm to the thick, matt black, redacted lines – that which cannot be revealed – and a real poetry to the way Holzer coats the remaining area in silver or gold, scratching visible words into their surfaces, revealing the treasure of what remains on the page, asking questions of what is valued and why. I am particularly moved by the canvases that contain one huge handprint, rendering these abuses and abductions personal: the owner of the hand’s name is scratched at the top of the painting.

There is also a welcome opportunity to step back and reflect on Holzer’s sources, with the aforementioned Inspiration Room; Louise Bourgeois is here, as is Paul Thek, Alice Neel, Keith Haring, George Grosz and Kiki Smith. I admire the honesty with which Holzer shares these original sources; it enriches the sense of who she is and why she does what she does. I love, in particular, the fragility of Smith’s deer drawing (Untitled, 1999) exquisitely rendered in ink on a large crumpled piece of brown paper that has clearly been folded and refolded. There are many such wonderful drawings – a discipline that Holzer has described as a form of “thinking and knowing”.

[image20]

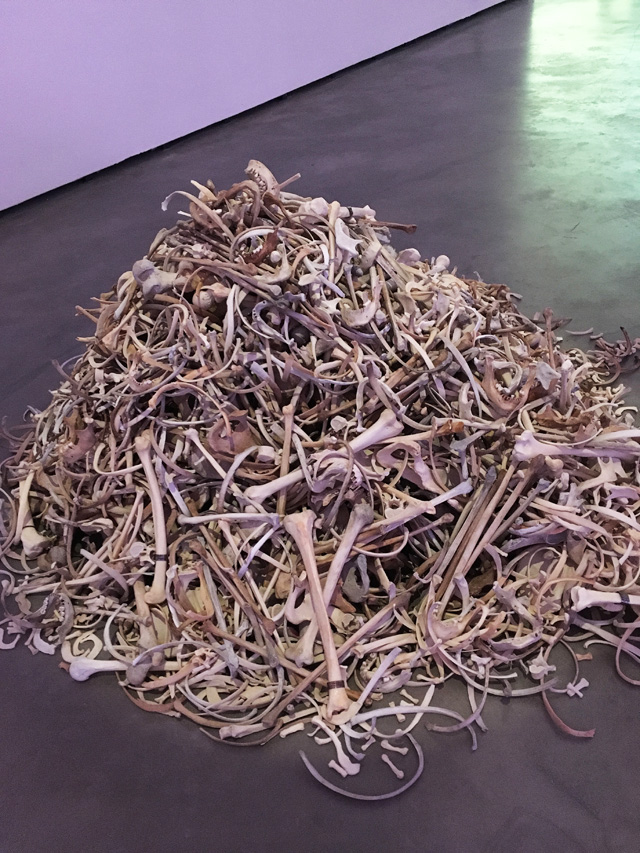

After this welcome light relief, we encounter the grimness of the last works of hers: Sworn Statement (2018) and Ram (2016). Sworn Statement hangs from the ceiling, blurting out abuses by US military personnel and their staff in the Afghanistan war, while its lofty position highlights the impunity they usually enjoy. Ram, in contrast, lies on the floor, undulating physically back and forth into the corner of the room – a movement that implies both battering rams and sex. A rainbow-tinted parade of letters that blip up at the end and march along its length are words taken from a selection of poems from Świrszczyńska’s 1974 book Building the Barricade. Sprinkled around this work is a ghostly selection of human shoulder bones – Holzer has been slowly acquiring ethically sourced human bones to use in her works since the 1990s. I find the practice slightly questionable: a great pile of them – including leg bones – has been fashioned into a mound nearby, serving what purpose I’m not sure, except to horrify.

[image13]

Holzer asks the journalists, during her opening press conference, for thoughts on what exactly this exhibition’s “Thing Indescribable” is? I suggest compassion, clarity, a willingness to listen, to bear witness. But a disquieting thought pops into my head on the curator’s tour as we reach the crumpled marble benches in the third gallery and I listen to the curator, Petra Joos, discussing the humanitarian workers whose efforts to help – and the testimonies of those they have helped – being engraved on the marble. I look at these priceless, undoubtedly expensive, artworks and the phrase “profiting from other people’s misery” wafts into view.

I put this question to Holzer – as respectfully as possible - while she stands answering journalists’ questions in the gallery. I say: “As a person of great conscience and compassion, how do you reconcile the fact that these works, inspired by so much human misery, will end up being monetised. Especially these marble benches?”

She answers: “It’s not possible to resolve entirely. I don’t know whether this is a defensive answer. It makes it possible to work. It keeps me on the straight and narrow that my prices are nothing like my male peers’ prices. I guess I can feel good about that. (laughs) I don’t have a couple of townhouses and those accessories. Anne Carson (the poet) and I have talked a little about this. She’s militant on the subject and she helps me keep my compass at least slightly right. When in doubt talk to Anne Carson.”

Did Holzer just dodge a bullet?

_1997.jpg)