Petit Palais, Paris

11 December 2018 — 17 March 2019

by JOE LLOYD

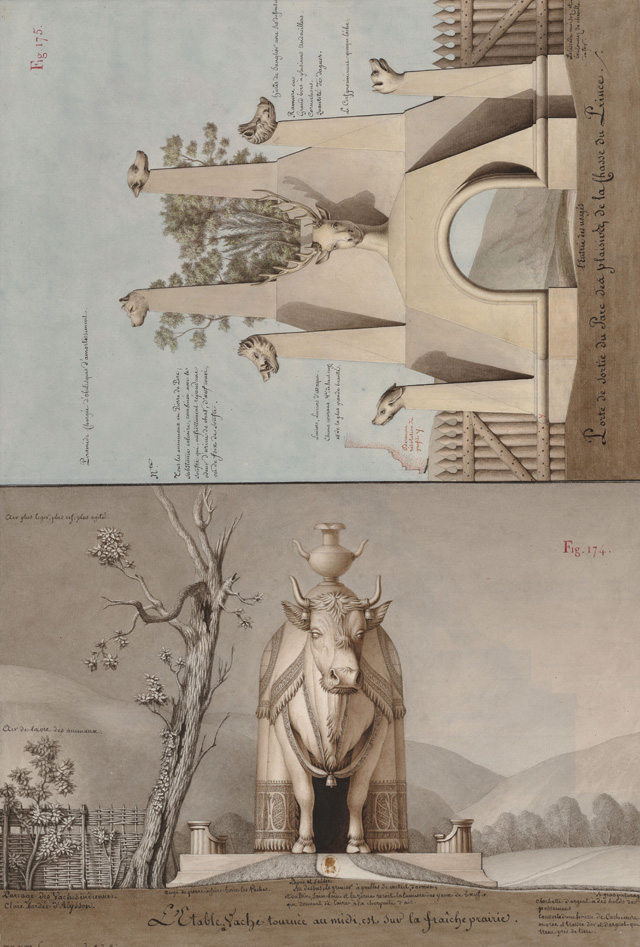

The architecture of Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757-1826) defies easy categorisation. The French draughtsman drew buildings so removed from architectural convention that they appear to have emerged from a feverish dream. He drew stupendous monuments, overloaded with so much decorative detail that, if executed, they would soon collapse under their own weight. He combined influences from the far east, ancient Egypt, Greek, Roman and Etruscan antiquity, medieval romance and the theatricality of the rococo. He designed a cattle barn in the shape of a giant bull, an Indian-inflected glass pleasure pavilion to be sunk underwater and accessed only through secret passages, and a temple of the sun with spiky stone rays, built to crown a mountain range. It is little wonder that nothing he put to paper was ever built.

[image3]

Ignored for decades after his death, when Lequeu did re-emerge in the 20th century it was as an eccentric analogue to the visionary architecture of his older contemporaries Étienne-Louis Boullée (1728-1799) and Claude Nicolas Ledoux (1736-1806). But whereas Boullée and Ledoux attempted to take neoclassicism to a heightened enormity and heroic austerity, Lequeu seemed a frivolous figure, caught up flights of fancy with no discernible schema. He can seem a long way away from the rationalist spirit of the Enlightenment.

A new exhibition at the Petit Palais in Paris, which packs in around 150 of Lequeu’s drawings, provides a welcome reassessment. Based on the holdings of the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF) – to whose predecessor, the Bibliothèque royale, Lequeu donated more than 800 drawings in 1825, after repeatedly failing to find a buyer for them – it spans the full scope of his curious practice. It makes clear that Lequeu was, among many other things, a man of his time. His ideas and attitude owed something to the ethos of the Encyclopédie (1751-1772), Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d’Alembert’s heroic attempt to gather together the world’s knowledge. However, whereas the Encyclopédistes used text as their medium, Lequeu used architectural drawing.

[image5]

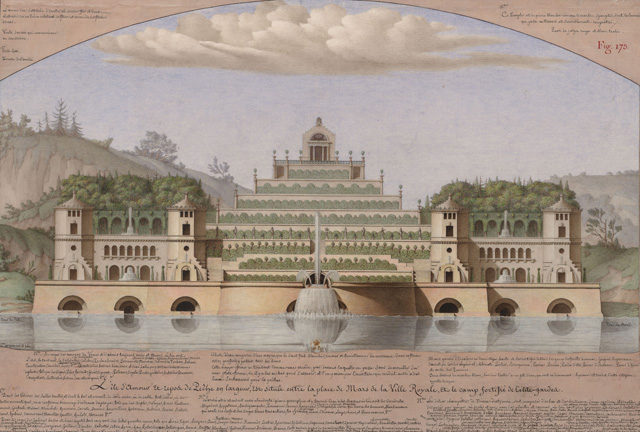

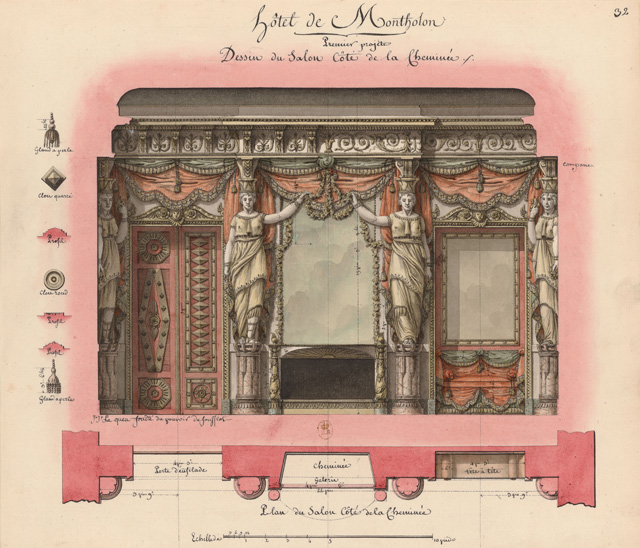

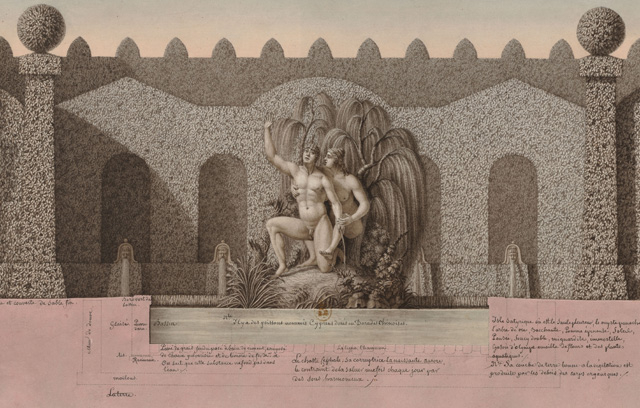

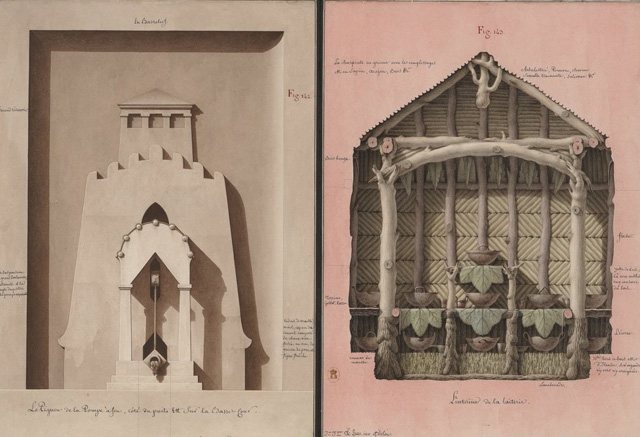

The ripest fruits of this exploration are collected in Architecture Civile, an unpublished portfolio of drawings, probably begun in the early 1780s and added to over the subsequent decades. It collects dozens of bizarre buildings, monuments and horticultural fantasias, often juxtaposing them in almost equally bizarre ways. One plate, for instance, features a Chinese-style pavilion, the featureless wall of a factory and a rustic hermitage; another places a menacing Castel Sant’Angelo-esque fortress at night above a windmill at the break of dawn.

Throughout, Lequeu adds notes, mostly meticulously descriptive, but some mystical: “the flesh-eater,” reads one especially bizarre example, “firmly divided into three graves, is covered by slabs of marble.” The sensation of scent, whether good or bad, is a particular obsession. One of his most compellingly odd designs, for a hunting lodge mounted with the heads of dogs, boars and deer, he specified the use of “lapis foetidus,” a stone Lequeu claimed bore the odour of cat urine . Textual references – to Ovid and Plutarch, the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili and, on rare occasions, the Bible – turn some of his buildings into staging posts for particular monuments of narrative. All are distinguished by Lequeu’s formidable skill with India ink and watercolour. He was a meticulous draughtsman, with obsessively precise lines and vivid shading.

[image9]

Lequeu was born to a family of master carpenters in Rouen, and his talent for drawing emerged at a young age. In about 1770, aged 12 or 13, he enrolled at the Rouen School of Drawing, where he won a succession of awards. This success led him to work for the local architect Jean-Baptiste Le Brument, for whose neoclassical church Saint-Madeleine de Rouen he drew the dome. A drawing from 1775 shows Lequeu skilfully considering the feature from different perspectives and elevations. After winning a prize for a designing a monument to the glory of Louis XVI, he was granted a two-year stipend to further his career in Paris.

It all began so well: arriving in the capital in 1779, he swiftly became a draughtsman in the office of Jacques-Germaine Soufflot, then engaged with the Church of St Geneviève (now the Panthéon). His support granted Lequeu a place in the prestigious Royal Academy of Architecture. But a year later Soufflot died and, without his patronage, Lequeu found himself out of both work and the academy. For the remaining 46 years of his life, he held a succession of government posts as a draughtsman and cartographer. Such positions were seldom well-paid and, following his retirement in 1815, he lived on a meagre pension.

[image4]

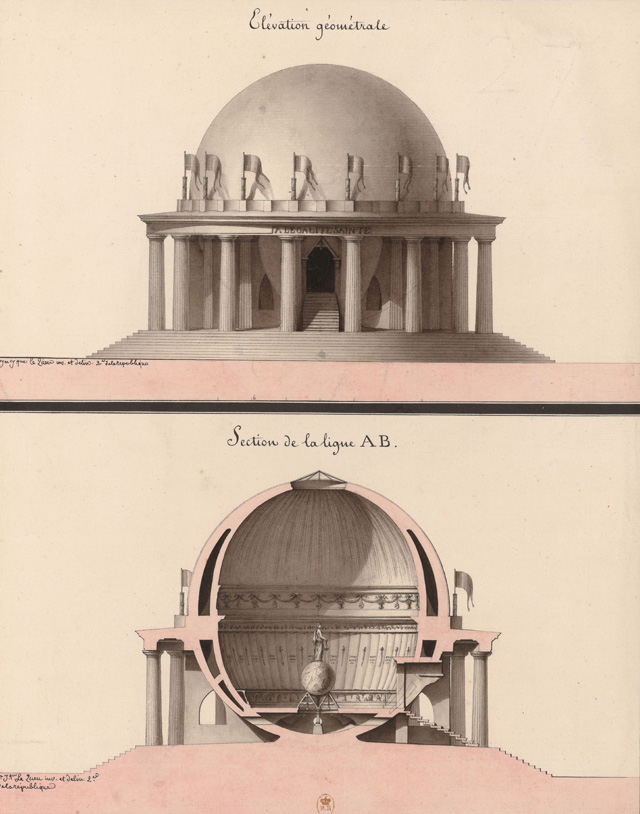

Until his bitter final years, Lequeu remained hopeful that he would one day be able to build. He entered almost every major competition. In 1794, at the height of the Reign of Terror, he submitted designs for a Revolutionary Temple of Equality, a rotunda-shaped Citizens’ Assembly and a fabulously overwrought Monument to Great Men comprising layer after layer of statuary and wreathes. Although Lequeu was a member of the Popular and Republican Society of the Arts – a hardline, Terror-supporting group – he also wrote “a drawing to save me from the guillotine” on the back of the monument, suggesting that his revolutionary engagement might have stemmed more from self-preservation than true zeal.

For Napoleon, he wished to create a triumphant palace faced with statue-bearing columns, which would meld classical, Renaissance and Egyptian features together. A few years before his death, Lequeu proposed two altars to celebrate the grandson of the restored Charles X, one of which was festooned with the heads, torsos and forelegs of seven stags. This willingness to move with the times led him to adapt some of his buildings: a 1794 design for a Temple of Supreme Wisdom was repurposed, with alterations, as a Temple for St Louis, the monarch-king, before finally becoming a Temple of the Earth, whose interior would be surmounted by glittering stars.

[image8]

This temple – a perfect globe fringed with columns – is a novel creation. Its form links Lequeu with Boullée and Ledoux, both of whom drew buildings with an orb form, albeit of an even more unbuildable magnitude. An extant contemporary parallel is found in the garden follies of the period, which, like the works of Lequeu, often drew on classical models. Designs such as the Grove of Aurora or the foreboding Porch to Pluto’s Demesne are an extension of this phenomenon. A further analogue can be found with the doomed gargantua that littered the 19th century, such as William Beckford’s Fonthill Abbey and Napoleon’s Elephant of the Bastille. The latter – a 24-metre-tall bronze pachyderm with opulent ceremonial chambers and gardens, never erected but represented for several decades by a mouldering, rat-infested plaster scale model – could have leaped right from the Architecture Civile. Lequeu was unique, but his singularities tend to stem from stretching and warping contemporary mores.

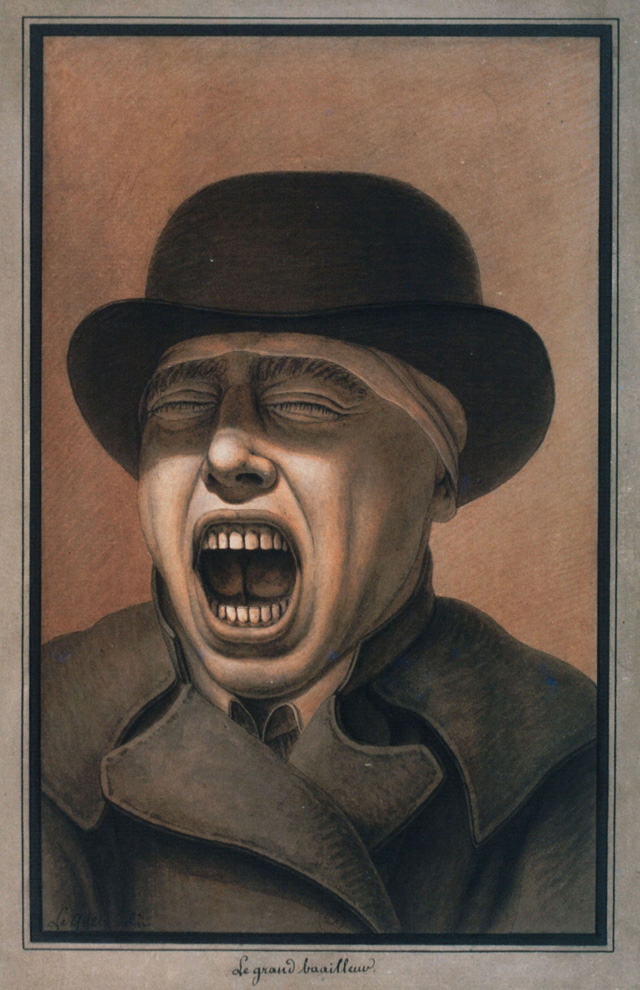

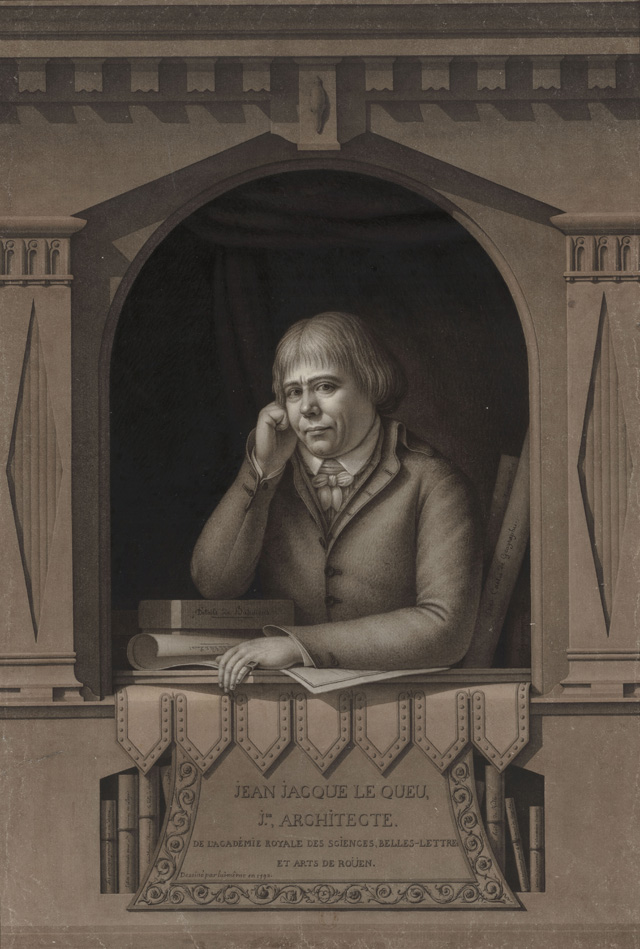

In his near-endless attitude to trying out different architectural styles, Lequeu could be considered a visual essayist. This method might also apply to a series of drawings with a rather different subject: himself. The exhibition at the Petit Palais includes a sequence of respectable self-portraits and a series of character sketches in which he adopts outrageous poses and outlandish garb. For one, Pouting Man, he appears topless, dressed in ragged headgear and with his lips puckered; in another, The Great Lessor, he appears in an overcoat and wide-brimmed hat, eyes closed and mouth agape in either a yawn or a scream. They are redolent of the contemporary work of the German sculptor Franz Xaver Messerschmidt, who claimed to derive his nightmarish forms from encounters with infernal spirits.

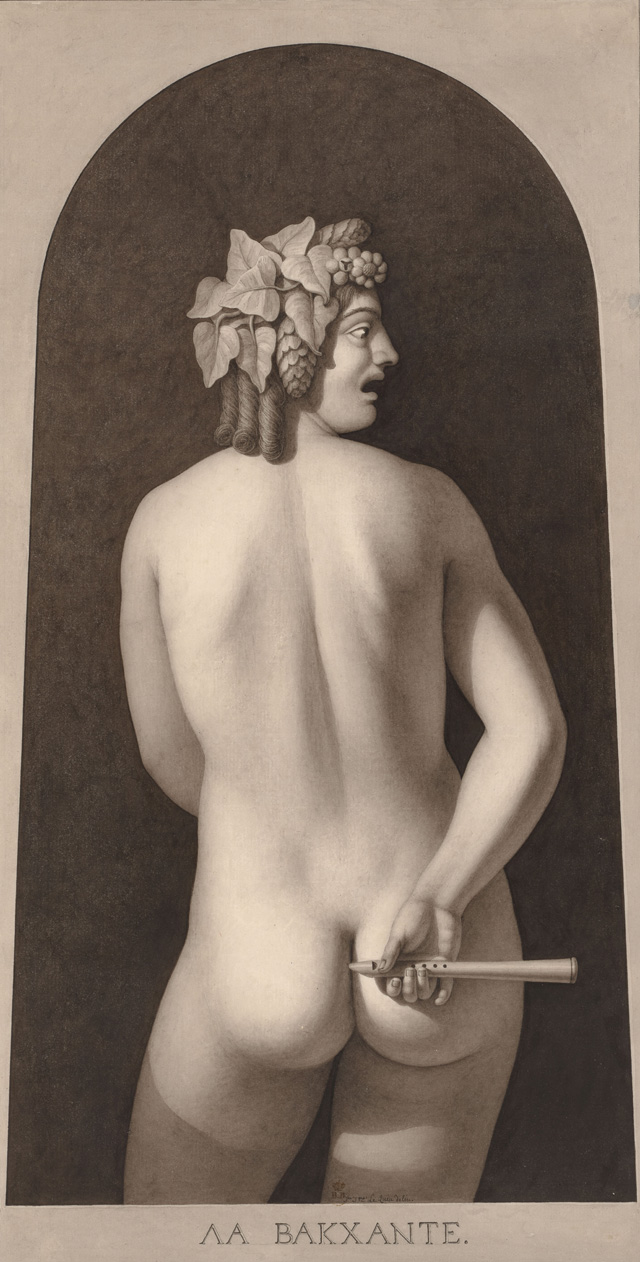

Often interpreted as a sign of mania, these pieces could equally be said to serve as parodies of physiognomy, or to bring Lequeu’s encyclopedic instinct to bear on his own flesh, or both. A more sinister manifestation of this work appears in the profusion of erotic imagery he drew, held in the BnF’s notorious department named L’Enfer (Hell). Lequeu drew dozens of female nudes, some mythologically inspired and others rendered matter-of-factly from life; there has been speculation that he lived above a brothel. He also drew genitalia. One drawing, which depicts a minutely detailed penis atop a male torso, is drolly entitled The God Priapus, after the recently discovered phallic deity. More unpleasant are a series of anatomically correct drawings of adolescent vaginas, which stand at the knife edge between knowledge-seeking Enlightenment and frustrated depravity.

Lequeu’s true purposes here, as elsewhere in his work, remain essentially enigmatic. We are able, thanks to the effort of the Petit Palais’ curators, to build his foundations and walls, but it is still difficult to know exactly what lies inside. This mysteriousness makes Lequeu endlessly fascinating. His failure to translate fantastical possibilities into prosaic, revealing concrete has proved to be his gift to posterity.