by JANET McKENZIE

One of Australia’s leading artists, Janet Laurence, has, since the 1990s, addressed the critical issues facing the environment in the epoch of the Anthropocene. She creates visually immersive environments, imploring us to address the mutability of nature, science and memory and the human destruction of the natural world. “The ecological crisis demands us to shift our focus from a human-centred perspective to a broader multi-species, environmental approach,” she says. In 1986, when Studio International published an Australian issue, her work as a flying artist was reported. Viewing the land from the air and visiting remote Indigenous settlements enabled her to identify that, just as colonial artists since 1788 had perceived the alien landscape through the eyes of Europeans, colonial farmers had introduced farming methods that have, over time, wreaked havoc on the environment. In response, her work seeks to encourage an ability to listen to nature, to immerse oneself in the exquisite and unique environment of Australia.

[image16]

The conceptual language of Joseph Beuys inspired Laurence, now 73, to develop her own language. His Vitrines works are key for Laurence in enabling matter to be transformed into meaning, where nature can be transfigured into cultural manifestations. Beuys’s dedication to environmental issues in his collaborative planting of 7,000 oak trees, instigated at Documenta 7, in 1982, came to be synonymous with the green movement. His project symbolised a grand vision beyond the confines of conventional art space; his artistic and ecological intervention inspiring generations to follow.

In this context, Laurence’s impassioned plea can be positioned in the vanguard of the climate change debate. Her indefatigable spirit has resulted in a wide range of exhibitions since 2010, when Studio International reviewed her Sydney Biennale exhibition Waiting – A Medicinal Garden for Ailing Plants, at the city’s Botanical Gardens. Then, she explained that alchemy is central to her conceptual approach and to the processes employed in her art practice: “As a philosophy, I was drawn to its holistic nature, its connecting of the body, psyche, and the elements. This was particularly important as a woman artist searching for another language, from the dominance of the western separation of man from nature. As an artist wanting to reconnect with nature, it offered avenues, in both action and symbols.”

[image5]

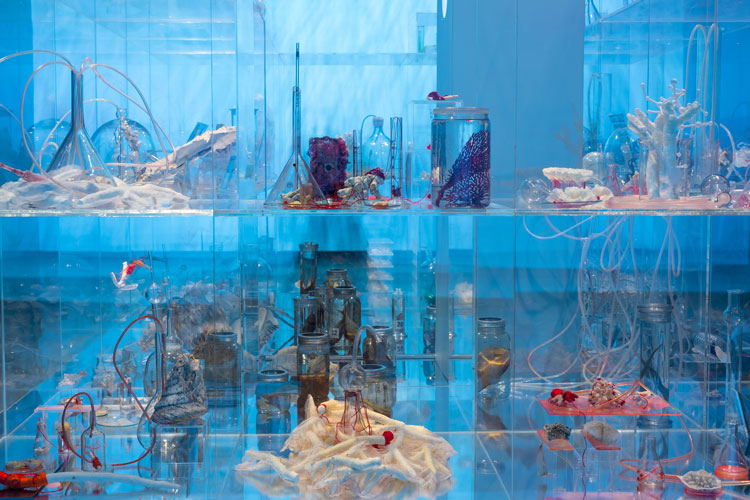

In 2015, Laurence presented Deep Breathing: Resuscitation for the Reef, for the Paris Climate Change Conference and the Paris International Contemporary Art Fair, followed in 2016 by the installation Deep Breathing at the Australian Museum, Sydney.

Her major survey exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia last year, Janet Laurence: After Nature, encompassed 30 years of her remarkable practice, including works such as: Vanishing, Forensic Sublime, Birdsong, Deep Breathing and Cellular Gardens in parallel with Theatre of Trees at the University of Sydney. As she explains: “I create elemental and fugitive spaces that express ephemerality through a language of veiling, transparency and translucency to form enmeshed environments, slowed spaces that express porosity and fluidity and a fusion with the environment. There are no boundaries, but membranes.”

[image4]

In Bonn, in October 2019, Laurence collaborated with the Zoological Research Museum Alexander Koenig for Nach der Natur, an exhibition designed to allow an encounter between life sciences, ethics and art. In Shanghai (2019-20), she exhibited in a group exhibition on sustainability, Continuous Regeneration, with 30 artists and designers, to address the issue of environmental protection. Her solo exhibition The Entangled Garden of Plant Memory, which opens this month at the Yu-Hsiu Museum of Art in Taiwan, presents a garden designed to bridge art and science. The show includes installations of suspended glass and plant matter, photographic and video works, seeds, specimens, ore, soil and objects from the historical botanical collection from the National University of Taipei.

Laurence was the artist I felt compelled to call as bushfires raged in Australia, creating apocalyptic scenes and unprecedented terror, with the loss of unique flora and more than a billion animals. In an attempt to comprehend the nation’s loss, and the ramifications internationally, one also questions what artists can do to accelerate the process to bring about change.

[image9]

Janet McKenzie: What a terrifying summer Australia has experienced. Your art practice has addressed environmental issues since the 1990s. Can you describe the state of the nation in the aftermath of this disaster?

Janet Laurence: Shock, horror, despair, shame and anger, and the realisation that it should never have happened. Scientists have been warning us of the danger of out-of-control bushfires for years. The government reduced funding for all environmental issues from rivers to national parks and their maintenance, while continuing to support coal mining. The big concern is that government bodies won’t be able to manage regeneration because there’s a huge division between those who simplistically want to clean up damaged trees and those who recognise that there is a great deal more to achieving a well-managed environment. Australia is a dry country and subject to drought. The tragedy of this summer’s shocking fires is the astonishing loss of our native animals. At least this aspect of the disaster is a reality and a tragedy that has prompted most people to admit that Australian animals are unique and we need to care for them.

[image11]

JMcK: In November last year, you were included in the group show Continuous Regeneration in Shanghai. Can you explain how the exhibition was conceived and what it sought to achieve?

JL: The Shanghai exhibition sought to bring together a vast range of different artistic design practices, including fashion that addressed sustainability and climate change. It was a very ambitious project and the vision and responsibility of one woman, Li Yemeng, in a beautiful space in Shanghai, an ex-French club in Columbia Circle. The show included an interesting seminar and opening with themed food and drinks and performances.

[image8]

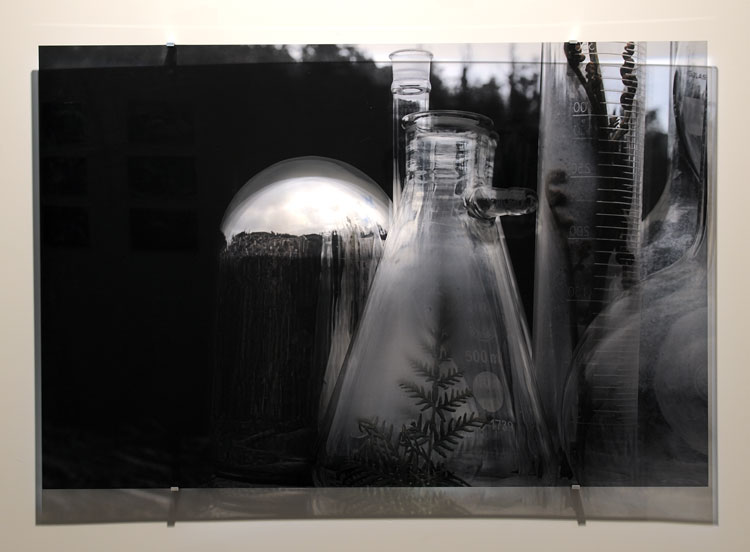

JMcK: When Continuous Regeneration opened, the bushfires had been burning for two months, very much earlier than the usual bushfire season. Your work Desire: Elixir Lab (2018-) was a prescient installation under the circumstances. Can you describe the piece?

JL: Elixir Lab is an ongoing work that evolves with each iteration and one that can be adapted to different places according to the plants and the medicines available in situ. In the case of the most recent Shanghai exhibition, it was using Chinese medicines, which made it different from previous versions. They were also put into a layout installation that resembled a glass garden. Initially, I wasn’t able to attend for the installation so I had to create and send it from my Sydney studio in order that it could be installed there without me. In the end, I attended the opening and the seminar.

[image3]

JMcK: The discordance between European agricultural practices and the Australian landscape became an issue for you in the 80s when you were a flying artist. Can you explain the unusual position and what you learned?

JL: What I learned from the flying art school was that some of the big sheep stations that I knew as a child suddenly looked like arid desert lands. They were very depleted and depressed compare with my memory of them and, of course, that change had taken place in a very short time. It prompted me to look at the question of farming practices since colonialisation and it was clear how unsustainable they were.

I realised, too, that white Australians didn’t have a way of seeing our landscape; my job as a flying artist was to travel to remote properties and to teach or encourage artists to work with what was there in front of them. I found that they did not really look at what was in front of them; instead, they were painting a version of the imitation of landscape that the first white artists to Australia in the 18th and 19th centuries produced. Early European ideas of landscape bear no resemblance to the Australian bush. It was an amazing grounding to have had.

[image18]

JMcK: After Nature, at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, was a superb exhibition and with the curator, Rachel Kent, you focused on your methodology. How it has evolved?

JL: One learns from every project.

JMcK: You have worked collaboratively with architects, scientists, farmers, poets and philosophers. In the present crisis, how do you believe this will garner support for the climate crisis?

JL: This is what I’m thinking about now doing – holding workshops and planning a requiem show to bring different thinkers together. It is necessary to share ideas and generate possibilities and this is an action that will create a space for hope.

JMcK: You were once criticised, by a Sydney newspaper journalist, for making work that appealed to a radical audience and the visitors to your pop-up water bar were described as well-hydrated communists? How far has the recognition of climate change come in Australia since then with politicians and the media?

JL: Not far enough!!

JMcK: What is your exhibition this month in Taiwan about?

JL: The Entangled Garden of Plant Memory is very much a reflection of the local landscape in Taiwan, interwoven with a lot of my other work that addresses the fragility of nature and climate change. As with most of my work, the exhibition will evolve as it is installed.

• Janet Laurence: Entangled Garden for Plant Memory opens at the Yu-Hsiu Museum of Art in Taiwan on 21 March and continues until 26 July 2020.

,-2018-19.jpg)