Institute of Contemporary Arts, London

21 September – 13 November 2016

by CELIA WHITE

Welsh artist James Richards (b1983) is known for using sound and moving image, whether created or appropriated, as sculptural tools to construct immersive and emotive digital installations. With his latest offering, Richard stages a multisensory triptych in the ICA’s three large exhibition spaces, with the intention of forming visual and aural resonances across the works installed there: the sound piece Crumb Mahogany (2016), the film and audio work Radio at Night (2015) and the slide installation Rushes Minotaur (2016).

Despite his evident skill at weaving familiar motifs that repeat themselves throughout the three spaces, Richards’s ambition of creating his own internal language, or even logic, across the triptych could be construed as narcissistic and perhaps even alienating for viewers. The three rooms offer possible interpretations and experiences that the search for Richards’s preconceived patterns might restrict. The lower gallery’s sound piece, Crumb Mahogany, for instance, features complex strata of sounds that oscillate between noise as stressor and as calmative: rumbling tyres, soft bonging, whispers, screeches, the clacking of a typewriter – many electronically warped such that they play on different emotions when received by different ears.

What is not encouraged in Crumb Mahogany is narrative and order, and there is a curious, though vague, etiquette for being in and around the piece. Once in the room, the audience gathers awkwardly in a central seating area surrounded by the speakers: there is nothing to look at and the lighting is stark, preventing the form of solipsism that is usually provided by the black box, and it is amusing to see new people enter and approach the pen of visitors with trepidation. Unfortunately, this “penning in” and the provision of benches discourages visitors from walking around the room, as if these erratic sounds were to be absorbed passively, as at a concert. Moving around, in fact, makes the noises come alive; from this aural sculpture can be chiselled new planes and indents if the ears actively shift between the sheets of sound.

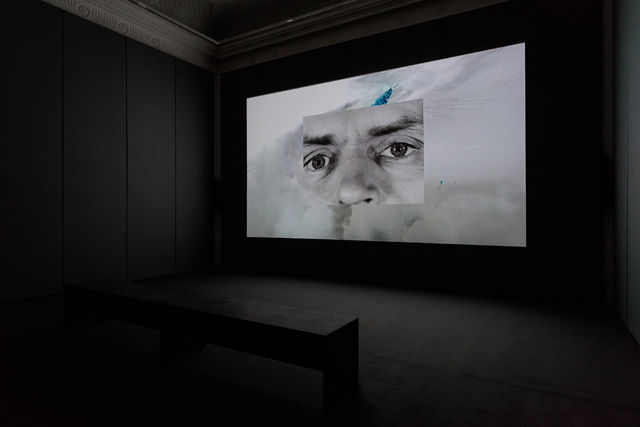

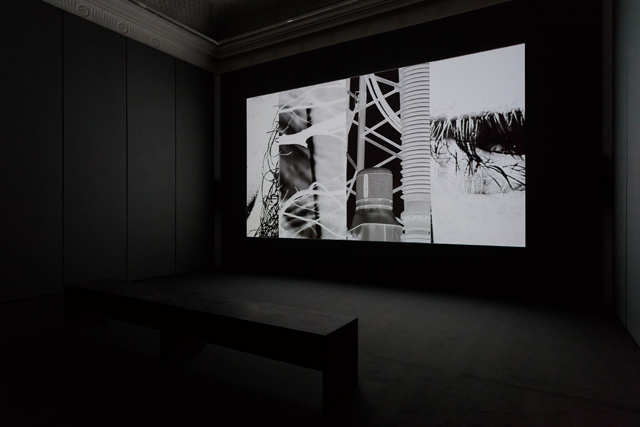

In the upper gallery, the video and sound piece Radio at Night seems to privilege style over substance. A sequence formed of found footage parades across the screen: Richards uses the reversal of black and white, the coloured inking of parts of a monochrome scene, and darkroom techniques such as solarisation, to coax an unlikely beauty from frames showing surgeons at work, dead pigs hanging from hooks, and microscopic images of hairs. A long sequence of home movie-style footage of elegantly dressed people at a masquerade ball, accompanied by a sweet, breathy vocal soundtrack, creates an eerie feeling of peering into an undated time capsule.

Though captivating, Radio at Night seems to offer little more than a visual feast. Could the many references to eyeballs, eyelashes, lenses and shifting irises be a reflection on the act of looking and, more specifically, on visual attention, focus and distraction? If so, these remain undeveloped, as if a token gesture has been proffered in the general direction of an idea or theme, but with its sophistication ultimately sidelined.

One of the few resonances that can be found between the works that make up this tripartite show appear between Radio at Night and its neighbour, Rushes Minotaur. In the latter, panels of light projected on the walls with still imagery sliding through them reconjure the laboratorial aesthetic of the video work next door. The slow encroachment of one photograph across the breadth of another also evokes a sense of the artist’s hand: leafing through film footage, making formal choices through experimental overlaps and image edits. This brings to light the forensic approach that is involved in cutting together disparate imagery and sound, and therefore credits Richards’s creative process more than the works themselves, experienced as artworks proper, seemed to do.

While certainly evocative, Richards’s show treads the razor-thin line between the elliptical and the vacuous. This can leave it feeling unremarkable and a little pretentious, even where it delights. It is unsurprising that Richards was shortlisted for the Turner Prize in 2014, when the penchant for film work comprised of found footage was just past its peak, but whatever he produces when he represents Wales at the 2017 Venice Biennale, it will no doubt work well in the small and dedicated space of a pavilion. What his ICA show lacks in ideas it makes up for in beauty, such that his work could provide a welcome breather for the addled biennale-goer.