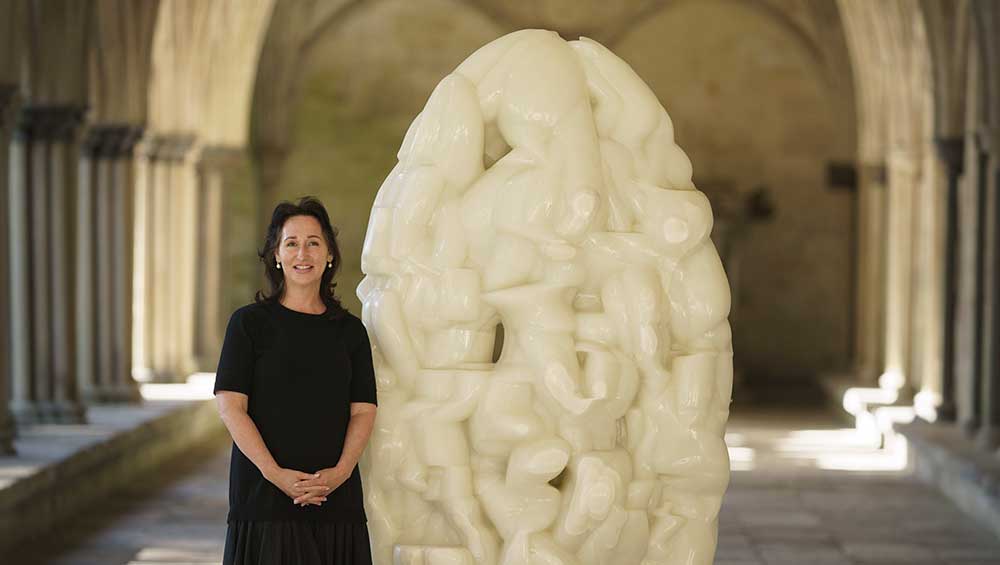

Jacquiline Creswell portrait. Photo: Ash Mills. Sculpture: Sail, 2016 by Tony Cragg, White Onyx 220 x 114 x 34 cm. Courtsey of the artist and Lisson Gallery.

by DAVID TRIGG

For 12 years Jacquiline Creswell (b1965, London) was the driving force behind Salisbury Cathedral’s pioneering visual arts programme, which saw world-class art exhibited in and around the 13th-century place of worship. Between 2009 and 2021 she organised more than 45 exhibitions at Salisbury, Ely and Chichester cathedrals, presenting enthralling installations and uplifting exhibitions that reflected on our shared humanity, encouraged spiritual responses and demonstrated art’s power to transform and renew. In this interview for Studio International she reflects on the role that art can play in sacred spaces, discusses some of her most memorable projects and picks out highlights from Together We Rise, her new group exhibition at Chichester Cathedral with artists from the Royal Society of Sculptors.

Raised in South Africa in a Jewish family, Creswell studied art and graphic design in Johannesburg, specialising in sculpture. Earlier in her career she worked for several advertising agencies, ran a successful textile design business, travelled all over the world and practised as a sculptor before the demands of motherhood intervened. Returning to art in the 2000s, she began stone carving with two stonemasons who had worked at Salisbury Cathedral. “I’m a great believer in things happening for a reason,” she says, reflecting on her journey. “I feel that all the steps in my life were leading me on a specific path that I was meant to take.”

It was through working with the stonemasons and helping a friend with a fundraiser at the cathedral that she was first drawn to the awe-inspiring space, but it was seeing Emily Young’s Angel Heads exhibition there in 2008 that really piqued her interest in the intersection of art and faith. “Young’s Purbeck stone angel heads made me see the cathedral in such a different way,” Creswell explains. “The exhibition attracted the congregation, but also people from outside the community, such as myself, a practising Jewess. I noticed how the works sparked discussions because of the context, how the building was altered by the sculptures and how the cathedral altered perceptions of the sculptures. Sacred spaces are places for reflection and contemplation; all the senses are set to slightly different frequencies in them.”

Sean Henry, Conflux installation view, Salisbury Cathedral 2011. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Ash Mills.

“I was a practising artist at that time and I got talking about these things to Canon Mark Bonney, who had seen some of my sculptures. Soon after, he called me in to discuss the possibility of running an art programme at Salisbury.” Having agreed to becoming Salisbury Cathedral’s visual arts adviser and curator, Creswell was immediately racked with apprehension. “In those days there was no such thing as a rolling art programme in churches and cathedrals, there wasn’t a curating in cathedrals course you could do, and there wasn’t a plethora of people who’d done this before that I could approach for guidance.”

For Sean Henry’s Conflux exhibition in 2011, Creswell sited 25 of the artist’s painted bronze figures on vacant plinths, tombs and open spaces inside and outside the cathedral. “You can’t exactly drill a hole in the wall, so you need to think of creative ways of installing work,” she says. Visitors to the show encountered a barefoot, suited man reclining on a tomb, a labourer in orange overalls standing in a niche and, outside, adjacent to statues of bishops and saints on the cathedral’s west facade, a black man holding a takeaway coffee cup. “That set up a really interesting dialogue,” she recalls. “It conveyed that the cathedral is not just here for the clergy; all are welcome and we’re all equal in God’s eyes.” Henry’s figures celebrated the individuality of anonymous men and women, inviting viewers to contemplate the cathedral’s role in the 21st century, as well as the evolving nature of contemporary art in places of worship.

Nicholas Pope, The Apostles Speaking in Tongues Lit by Their Own Lamps, 2014. Terracotta, approx 13.5 x 3.8 m. Courtesy of the artist and The New Art Centre Roche Court. Installation view, Salisbury Cathedral. Photo: Ash Mills.

“Visual art transcends the limitations of language,” Creswell says. “It’s a powerful communication tool that reaches far beyond the cathedral’s walls and touches people of different communities, faiths and backgrounds.” Several projects have shown how visual art can also enhance the cathedral’s worship services, complementing the liturgy and music. This was especially true of Nicholas Pope’s The Apostles Speaking in Tongues Lit By Their Own Lamps (2014), a dramatic representation of the events narrated in the Book of Acts, when God the Holy Spirit manifested among the Apostles in the form of “tongues of fire” resting on their heads. Comprising 33 terracotta figures crowned with flickering flames, Pope’s installation was presented in the Trinity Chapel during Pentecost and accompanied by a recording of the actor Harriet Walter reading from the biblical narrative. “It just brought the whole story to life for people,” Creswell enthuses.

Bruce Munro, Star of Bethlehem, 2014. Courtesy of the Artist. Installation view Salisbury Cathedral. Photo: Ash Mills.

Another powerful counterpoint to worship was seen in Bruce Munro’s Star of Bethlehem, commissioned for Christmas 2014. Taking the form of an animation projected over the cathedral’s famous Living Water font by William Pye, the work was a literal and visual abstraction of the text from Matthew’s Gospel, telling the story of the wise men following the star to find the infant Jesus. The words were translated into Morse code, appearing as pulses of light that formed a star; bathing the font in light, the biblical text scrolled along each of its points. “It was so moving”, says Creswell. “Some of the cathedral’s volunteer guides are ex-marines and they were able to teach visitors what the words meant.”

Each exhibition presents its own challenges with many considerations, from working closely with fabric advisory committees and the clerk of works, to estates managers, transport and installation teams, engineers, health and safety officers, and even archaeologists. One of Creswell’s greatest challenges came early on at Salisbury when her activities were met with hostility and suspicion from some in the clergy, congregation and wider community. “When I first started siting art within the cathedral, I was verbally abused and, in some cases, physically abused by people who didn’t understand the art. I was told that I was turning the place into a theme park. I quickly became aware that it was really important to inform the community, so my colleagues and I decided that, before any exhibition, we would give a presentation explaining the works and what we were trying to achieve. That made an enormous difference. Several years later, these same people who had been pretty rude to me were coming up and asking: ‘What are we going to learn next?’ I felt like a proud mother when I heard them talking so confidently to visitors about the art on display.”

Michael Pendry, Les Colombes, 2018, at Salisbury Cathedral. Courtesy of the Artist. Photo: Ash Mills.

In March 2018, Salisbury became the focus of a media storm after Sergei Skripal and his daughter were found poisoned by a deadly nerve agent in the city centre. “That really shook Salisbury,” says Creswell. “It was a terrible shock. It’s quite a small community here and we had men in the centre of town dressed in hazmat suits. Everybody was terrified.” Before the poisoning, the cathedral had been preparing to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the end of the first world war with the German artist Michael Pendry’s installation Les Colombes (2018), a soaring flock of more than 2,000 white origami doves suspended along the length of the nave. “We were in a real quandary, wondering whether we should be going ahead with the exhibition at all. People weren’t coming out of their homes and all the shops were closed.

“But doves are a symbol of hope, peace and, in the context of the cathedral, the Holy Spirit. So, we thought that perhaps the installation might be a way of bringing the community back together. We started installing the doves and invited people to come and fold their own, writing their prayers, fears and thoughts inside them,” says Creswell. Many of those birds joined the main flock in the cathedral, but others were taken home and displayed around the city. “Before we knew what was what, we had schools requesting paper for folding and every window in Salisbury was covered in white doves; even the inmates at Erlestoke prison started creating birds for the flock.” The installation had a significant impact on the community. “It created this really uplifting, warm and secure environment for people, which brought the community out of their homes and back into Salisbury. A lot of people visited in the evenings, just sitting there for hours. People felt as if they weren’t alone, that they were a part of something bigger, that people cared and that there was hope.”

Grayson Perry, Death of a Working Hero, 2016. Tapestry, 251 x 200 cm. Courtesy of the artist, Paragon Press and Osborne Samuel Gallery. Photo: Ash Mills.

The year 2020 marked 800 years since the foundation stone was laid at Salisbury Cathedral. The impact of that historic moment continues to resonate today, not only with the magnificent cathedral itself, but with the thriving city of Salisbury that grew up around it from medieval times. To commemorate the anniversary, Creswell organised Celebrating 800 Years of Spirit and Endeavour, the largest contemporary art exhibition at the cathedral for nearly two decades. “The theme of the exhibition was inspired by a poem by John Ormond called Cathedral Builders,” she explains. “It talks about the ordinary people who built the cathedral, working day and night in a spirit of faith to achieve something extraordinary.” Creswell spent three years planning the show, which through a selection of works by renowned artists – including Antony Gormley, Shirazeh Houshiary, Henry Moore, Grayson Perry, Subodh Gupta, Conrad Shawcross and Mark Wallinger – sought to explore different aspects of the human condition, demonstrating how faith, when combined with humanity’s indomitable creative spirit, can inspire great vision.

Henry Moore, Large Reclining Figure, 1983. Fibreglass, 340 × 900 × 310 cm. Photo: Ash Mills.

In March 2020, as the exhibition’s opening night approached, Covid-19 was spreading across the country. Social distancing had been introduced and galleries and museums were already closing their doors. It is no wonder that Creswell describes installing the show as the greatest challenge of her career. “We were racing against the clock to get all the pieces installed before the first lockdown. We were told that we would have to close doors and go home on 20 March; the exhibition was supposed to open on the 23rd.” Some of the works were monumental, including Moore’s nine-metre-long (29ft) Large Reclining Figure (1983). Others presented unique challenges, such as Gormley’s stainless steel figure Grip (net) (2019), which was placed high up in one of the cathedral’s scissor arches, 14 metres above the floor. Many pieces of specialist equipment were required, including cranes and a scissor lift, and it took more than 400 hours of commitment from engineers and professional installers, all carried out under the looming cloud of the national lockdown. “I felt largely out of my depth at that point,” Creswell admits, “but the team was amazing. The incredible effort that everybody made was a testament to the exhibition’s twin themes of spirit and endeavour.”

,-2019-by-Antony-Gormley.jpg)

Antony Gormley. Grip (net), 2019. 0.15 square section stainless steel bar. 193 x 48.5 x 38 cm. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Ash Mills.

Having spent three years working on the exhibition, it was a bitter blow for Creswell and her team to see the cathedral’s doors locked before the show had even opened. “When I got home, I cried for a good 48 hours,” she says. But all was not lost. Soon after, there came the suggestion to create a virtual tour of the exhibition using technology pioneered by the spatial data company Matterport. “That was a game changer. We managed to deliver the exhibition around the world to people who never would have come to visit otherwise. It’s fascinating to think that the people who built the cathedral would have had absolutely no concept of the idea that one day people would visit the space virtually from their homes.” During lockdown, the virtual tour was viewed by 19,000 people before the cathedral opened to the public again in July. The rules enabling people to leave their homes and exercise once a day meant that local people could visit the sculptures sited around the cathedral’s grounds. “The local community had, among others, a Henry Moore, an Elisabeth Frink, a Conrad Shawcross and a Barbara Hepworth to enjoy every day. People are still thanking me for that.”

Craigie Atchison, Crucifixion 8, 1985-86. Oil on canvas, 221 x 188 cm. Courtesy of Piano Nobile Gallery. Photo: Ash Mills.

Although Creswell has now left her role as Salisbury Cathedral’s visual arts adviser, she is still curating exhibitions in sacred spaces. This summer, Together We Rise opens at Chichester Cathedral, featuring the work of 26 artists based in south-west England from the Royal Society of Sculptors. Taking the pandemic as its starting point, the ambitious exhibition reflects on themes of hope and resilience in the face of human vulnerability. During lockdown, the participating sculptors all connected virtually for mutual support, meeting regularly via Zoom to find strength, encouragement and a safe space to share ideas and discuss their challenges, from self-doubt and feelings of being marginalised to anxiety about the pandemic and its impact on them and their work.

“I had worked with some of the artists in the past and they came to me to ask if I could organise an exhibition for them that summarised their experience of working together during the pandemic,” Creswell says. “They were quite keen on showing in a gallery, which I did explore, but then I realised that what these artists have to say would be far more profound in a sacred space.” The cathedral team were really interested in the proposal, but a lot of the artists had never worked in a religious building before and needed a little convincing. Creswell organised several visits to Chichester along with the cathedral’s visitor experience manager and chancellor, the Reverend Canon Dr Dan Inman, who injected a liturgical and theological dimension into the discussions. “We talked and walked the artists through the cathedral so that, when they left, they had a sense of the space and what happens there. Then we left them to come back with their responses. My job was to assist and advise the group to help deliver a coherent and cogent exhibition, bringing together and combining all the different threads in a way that truly expressed the potency of the collaboration in this sacred space, which is rich in history, culture and spirituality.”

,-by-Conrad-Shawcross,-2015.jpg)

17 Technicians installing Formation I (Dappled Light of the Sun), by Conrad Shawcross, 2015. Weathering steel, 792.1 x 792.1 x 475 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Victoria Miro Gallery. Photo: Ash Mills.

While the lockdown was an extremely challenging time for many in the group, its members supported and helped each other to see past these obstacles and create new, inspired works that often embraced fresh ways of working. The relevance of staging the exhibition in a religious space became fundamental to the show as the artists realised that their work could assist in the healing process of those recovering from Covid and its impact. “What’s been really important is linking the work not only to the narrative of the exhibition, but also to the context of the cathedral,” Creswell says. “The artists have already embraced a significant change in their practice during lockdown, but I wanted to challenge them to look at the sacred context, embrace it and incorporate it into their work. It’s been quite astounding how they have responded.”

Kate McDonnell, Twisted, 2022. Paper, dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist.

Among many stunning works on display is Kate McDonnell’s Twisted (2022), a flowing mass of tangled black tendrils suspended above the font. “It’s an amazing candelabra of cascading twisted paper,” says Creswell. “When she was at home in quarantine, all Kate had was this black tablecloth paper, which she started twisting in on itself, tighter and tighter, until it formed a chaotic mess. It reflects the anxiety caused by Covid; when you see it, you get a sense of that dark period which we all lived through, but at the same time it’s really beautiful.”

,-courtesy-the-artist.jpg)

Barbara Beyer, Possibilities, 2022, (Work in Progress), courtesy the artist.

A very different response is found in Barbara Beyer’s Possibilities (2021), a group of stoneware clay vessels that underwent a process of deformation during their creation, being deliberately dropped before being fired. “She has created these vessels in response to the cathedral’s shrine of St Richard,” Creswell explains. “The story goes that Richard had a goblet, which he dropped and broke, but when he picked it up, the chalice was still full of liquid and became whole again.” Beyer’s vessels may suggest a sense of loss and misadventure, but they also carry the message that healing is a possibility. “We’re going to place them all around the shrine. They’re a response to the cathedral, but also to the pandemic and how she felt during that time.”

,-2022,-courtesy-the-artist.jpg)

Dallas Collins, Resurrection, 2022 (work in progress), courtesy the artist.

In the south transept, Dallas Collins is showing Resurrection (2022), an installation responding to the stained-glass windows there. “He’s creating these beautifully coloured wooden beams, but they’re made of foam. The different colours reflect those found in the windows.” Piled in a heap on the floor, the beams evoke rubble from a demolished building, or perhaps the material from which something new can be created. “The piece refers to how the cathedral lost one of its towers many years ago, which had to be rebuilt, and he relates this story from the building’s history to the pandemic and the way in which, as a society, we’re having to rebuild something that’s been broken.”

Outside, in the cloister, is Anna Gillespie’s Fuse (2022), an 11-metre-long sculpture composed of sections of body casts taken from her fellow sculptors. It acts as a counterpoint to the extreme physical isolation that the artists felt during lockdown, taking their relationships with each other from the digital sphere into the physical. It is also a celebration of the human body. “I always like to have some art outside; it’s a hook that leads people into the cathedral to see what else is going on,” says Creswell.

As a counterpoint to the challenges of the last two years, Together We Rise embodies the artists’ perseverance and resolve to overcome their challenges. “By bringing together this group, much as other communities have come together during the pandemic to support one another, I have seen a flourishing of creativity, which demonstrates the power of shared adversity overcome by shared endeavour,” says Creswell. “The works in the exhibition echo and affirm the spirit of community and collaboration that brought the group together and the many challenges they faced. I hope that by reaching out to a wider community we might all be lifted up and inspired by their creativity.”

• Together We Rise is at Chichester Cathedral from 27 June to 6 September 2022.