Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin

29 March – 1 September 2019

by MATTHEW RUDMAN

How to represent Prince as an abstract image? What about Louise Bourgeois, BB King, or Stanley Kubrick? Pictures might come rushing up to the surface, but spend some time with it: what does their life and work mean – to you specifically and to society as a whole? It is a deeply personal exercise, one that can reveal as much about the individual as the subject. American artist Jack Whitten understood this: his “memorial” paintings – a generous selection of which are on show this summer at the Hamburger Bahnhof – are extraordinary not just in their beauty and artistic rigour, but also in their ability to communicate so much at once about both subject and artist.

[image7]

Jack’s Jacks may be too small to be called a retrospective, but it certainly marks an important moment. This is the first solo exhibition of Whitten’s artwork at a major European institution, and was curated in close collaboration with him. Whitten died in 2018 at the age of 78, a few months before a major exhibition at the Met Breuer in New York City that debuted his decades-long, but previously unseen, sculptural practice. The works on show at Jack’s Jacks are drawn from a career that spanned almost 50 years, and often seem more like sculptural works than traditional paintings, embellished with sparkling gemstones and richly coloured tiles. As the title suggests, these are personal paintings for Whitten: the majority of them were created as a “gift” to honour the memory of a recently departed major cultural figure.

[image4]

Whitten was born in 1939, in Bessemer, Alabama, and grew up in a time and place steeped in racial segregation and institutionalised bigotry. This upbringing shaped a keen interest in politics, civil rights and African American culture that stayed with him for life. He met Martin Luther King while attending a bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama, marking his death with the frenzied King’s Wish (Martin Luther’s Dream) (1968). Even late in life, Whitten remained engaged with the triumphs and tribulations of his nation, with paintings on show honouring President Obama and memorialising the victims of the Sandy Hook elementary school shooting.

[image5]

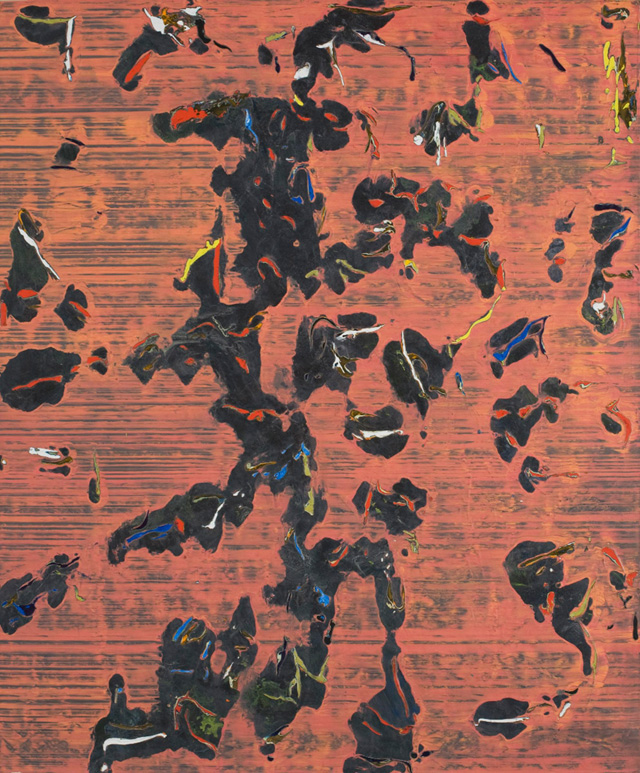

In 1960, Whitten relocated from Alabama to New York City, where he studied at Cooper Union. Abstract expressionism was the dominant style at the time, and Whitten learned from some of the most celebrated artists of the period: he was mentored by Willem de Kooning and Norman Lewis, and was acquainted with Franz Kline, Barnett Newman, Romare Bearden and Jacob Lawrence. Early paintings in the exhibition demonstrate Whitten’s indebtedness to the abstract expressionists. Zulu Tea Parlor (1973) is an archipelago of black oily slicks on a salmon-pink backdrop, its colours luscious and inviting. With Delacroix’s Palette (1974), we see Whitten experimenting with gesture, smearing the paint horizontally across the canvas, the resultant image resembling a Delacroix hurled through a category-5 hurricane.

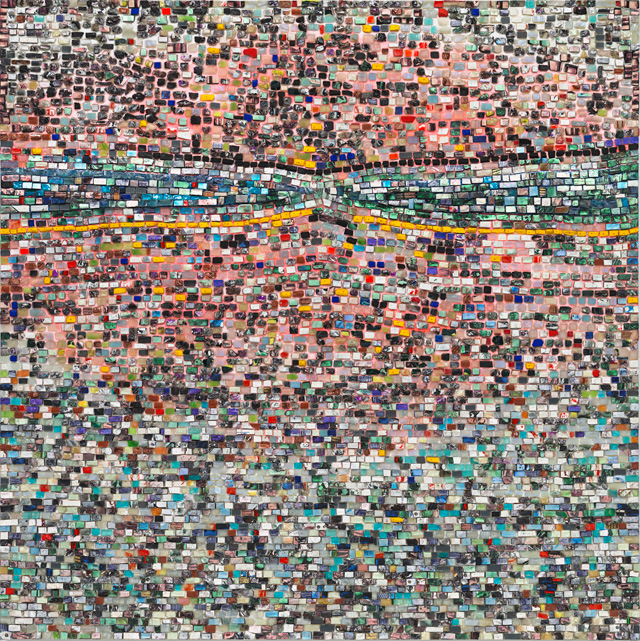

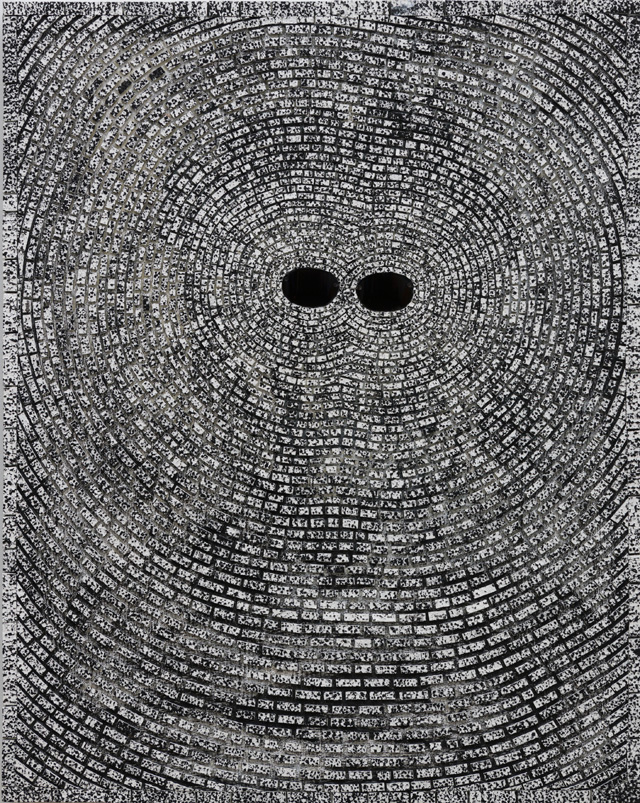

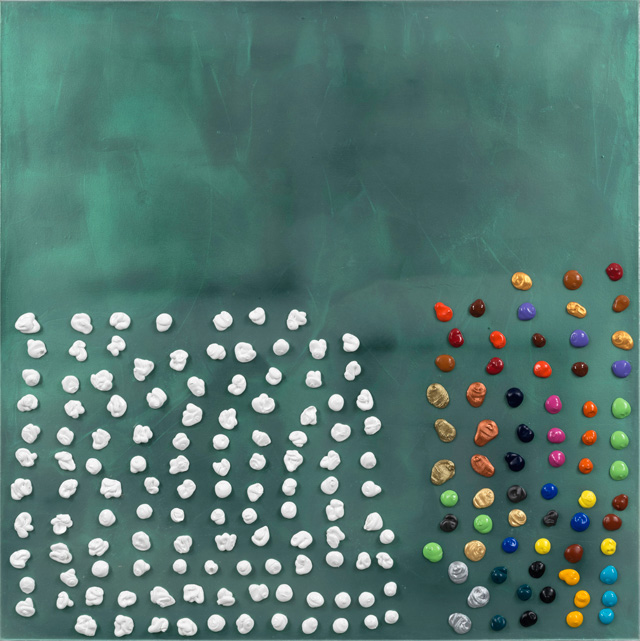

But Whitten was not one to ally himself so easily with a readymade movement. Moving deeper into the exhibition, works from the 1980s onwards see Whitten developing the distinctive style that has since become something of a calling card. He called them “tesserae” – tiles of dried acrylic paint, reacting unpredictably in the light, cut into all sorts of shapes, though never much larger than a fingernail. It was a painstaking process: each tesserae is individually fastened to the canvas support, which is itself painted in complementary tones, a dense layering of colour lending the paintings a mirage-like effect.

[image6]

In some paintings, the tesserae are uniform, arranged in tight, kaleidoscopic patterns, as with the arresting Self Portrait: Entrainment (2008), where monochromatic spackled tiles are carefully shaped to wrap around a pair of dark eyes in widening concentric rings. Other artworks are a patchwork of irregularly shaped tiles, earthy colours lending the pictures the quality of aerial photography. Quantum Wall a Gift for Prince (2016) is a standout piece, a huge, deep-blue triptych several metres wide, the precise colour is hard to pin down, subtly changing with distance and viewing angle.

[image2]

Whitten would often draw parallels between his painting style and jazz musician John Coltrane’s “sheet of sound” style, a term coined by jazz critic Ira Gitler. The liner notes of Coltrane’s album Giant Steps described these sheets as “multinote hailstorms of dense textures that sound like a simultaneous series of waterfalls”. A fitting accompaniment, then, to Whitten’s exacting paintings, which overwhelm the eye with their fragmented, staccato points of gem-like colour.

Almost every painting in this exhibition reliably delivers on an emotive one-two punch. First, the image, the colour: you notice the glistening tesserae, the luscious colour combinations, the absurdity of the sawn-off base of a wine glass upturned and painted as a bare breast. Then your eyes flick across – you note the title, the date, the person to whom this painting is dedicated, often couched within a title that takes the form of a direct address to the recently departed. Ellsworth Kelly; Arshile Gorky; Muhammad Ali. It is clear there are strong emotions at play here: these paintings are deeply personal labours.

[image9]

But part of the joy of them is how accessible they are to an outside observer: the exhibition reads like a scrapbook of great artists and musicians of the 20th century. Whitten’s paintings, while abstract, are extraordinarily expressive, with bold colours, rough surfaces, full of unexpected quirks of shape and texture. They are strangely expansive works, inviting meanings, reminiscences and interpretations, rejecting none. For while they may be Jack’s Jacks, we share these cultural touchstones with Whitten; in some small way we, too, know these people.