The Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia

19 June – 4 September 2022

by LILLY WEI

The five, glimmering, free-standing screens of Once Again … (Statues Never Die), the eminent Black British artist Isaac Julien’s recent film, are strategically placed around the Barnes Foundation’s principal gallery for temporary exhibitions, the walls panelled in silvery polystyrene to create a salon of mirrors, of illusions, and wavered, obscured doublings. In adjacent spaces flanking the main room, as part of the installation, several regal West African works from the Barnes’s celebrated collection – that is, celebrated for its priceless modernist masterpieces – are on display. The bias that comes down hard on the side of European art at the expense of African art is one of the main themes of this exhibition, with its circling debates about museum histories and policies, and the renewed demands for the restitution of the plundered heritage of others.

[image3]

There are also three bronzes by the sculptor Richmond Barthé (1901-89), an artist of Harlem Renaissance renown, creator of sleekly elegant images of the New Negro, and a character in Julien’s film, played by Devon Terrell (Barack Obama in Barry). Additionally, there are five translucent resin blocks by Matthew Angelo Harrison (b1989, Detroit) in which tourist carvings of African art are embedded, a further critique on colonialism and cultural valuation. All three parts of the exhibit raise thorny issues regarding the Black and white divide spanning a century in which Negro (and a less polite epithet) gives way to African American to Black – with (some) corresponding changes in attitudes, but not enough. Homoeroticism, homophobia and queer identity are also rolled into Julien’s project, one that encompasses a spectrum of ambiguities and complexities.

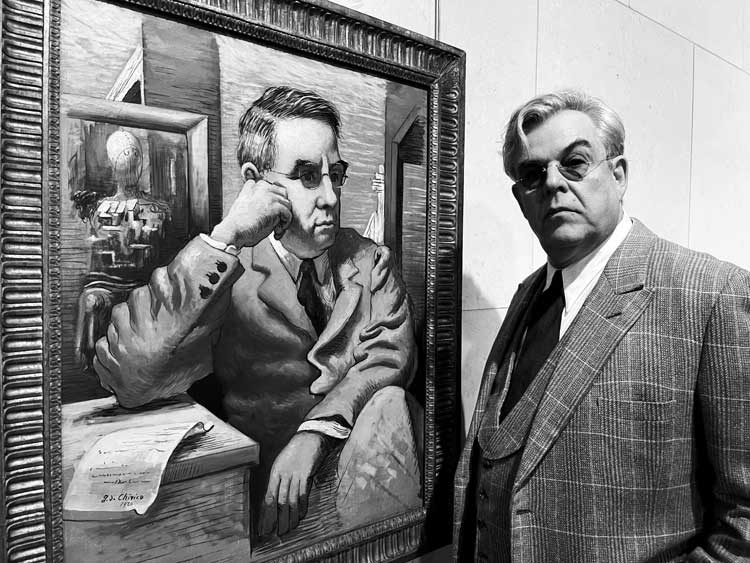

The roughly half-hour film was commissioned by the Barnes Foundation with the support of the Ford Foundation to commemorate the former’s centenary and was curated by its executive director and president, Thom Collins. Alain Locke, played by André Holland (Moonlight and Passing), is at the heart of this project, the African American author, critic, philosopher, teacher and aesthete, who was discreetly, but admittedly gay. Often acclaimed as the father of the Harlem Renaissance, he published his influential essay, Enter the New Negro, and the anthology he edited, The New Negro, in 1925. He is paired with the pharmaceutical magnate Dr Alfred C Barnes, played by Danny Huston (Succession and 30 Days of Night); look for the doppelgänger moment when Huston stands next to a portrait of Barnes). Barnes was an impassioned and eccentric collector of singular vision whose keen support of African and African American culture was capped, when he died in 1951, by his unexpectedly and controversially leaving the oversight of his collection to Lincoln University, a small, little known, historically Black institution with no previous expertise in art stewardship.

[image2]

Julien, who dived deeply into the Barnes’ archives, centres the film on an invented dialogue between Locke and Barnes, trading points of view based on their writings, backgrounded by white privilege, and a history persistently threaded by fetishisation, racism, homophobia, humiliation and far worse. It was Barnes who introduced Locke to African art, somewhat ironically, fascinated as he was by its relationship to modernism and to the works of the artists he collected – Picasso, for one. Barnes says, speaking to Locke in the film: “The work of the young painters such as Picasso, Modigliani, Soutine, for example, is to a certain extent, the work of the African emotion in a new setting. In the same way the sculpture of Archipenko, Lipchitz and of Epstein is impregnated with Africanism.”

Locke, in turn, gave Barnes access to contemporary Black artists and writers, and states elsewhere in their fictive conversations tweaking that comment that perhaps: “The most important effect of interpretations like these is to break the invidious distinction between art with a capital A for European forms of expression and “exotic” and “primitive for the art expressions of other peoples.”

In glamorous retro black and white – Julien can always be counted on for ravishing production values – in addition to archival images, he intercuts Once Again with footage from his breakout film, Looking for Langston (1989), adding quotes from Hughes as well as from Aimé Césaire, the Martinican poet and political activist whose Discourse on Colonialism is considered by many the standard text for anti-colonialism, and others throughout the film. The film also channels Chris Marker and Alain Resnais’ Statues Also Die (1953), a cult classic that was banned soon after its release in France for its condemnation of French colonialism and the looting of African cultural icons. The 1897 expedition of British troops that destroyed the ancient Kingdom of Benin is also referred to, reminding us how its magnificent bronzes ended up in the British Museum. There is also the recent discovery of archival footage from the film You Hide Me (1970) by the Ghanaian film-maker Nii Kwate Owoo that shows boxes of such lootings stored unseen in the vaults of the British Museum.

[image5]

The Curator, played by Sharlene Whyte (Small Axe and Lessons of the Hour), looks at it from another point of view and another point in time as we watch her stride purposefully through vast rooms (in the footsteps of Locke who preceded her) filled with endless vitrines of African art and artefacts. That turns out to be the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, England, much of its archaeological and ethnographical holdings the deracinated spoils of empire acquired under questionable circumstances. She says (the quote from Césaire): “And what of the museums, of which Europe is so proud? It would have been better, all things considered, if it had never been necessary to open them. Better if the Europeans had allowed the civilisations beyond the Continent of Europe to live alongside them, dynamic and prosperous, whole and unmutilated … Racism, no matter if it is declared or undeclared, drains all empathy away. No, in the scales of knowledge the mass of all the museums in the world could never outweigh a lone spark of human empathy.”

That these questions are presented through the lens of a Black artist, a Black point of view also matters. As Locke wrote in the foreword to his anthology: “So far as he is culturally articulate, we shall let the Negro speak for himself.” And more and more are, even if more voices are needed. As for the conversations about restitution, “they have been going on for a very long time,” Julien said. But he thinks the context is different now, and he is guardedly optimistic.

[image6]

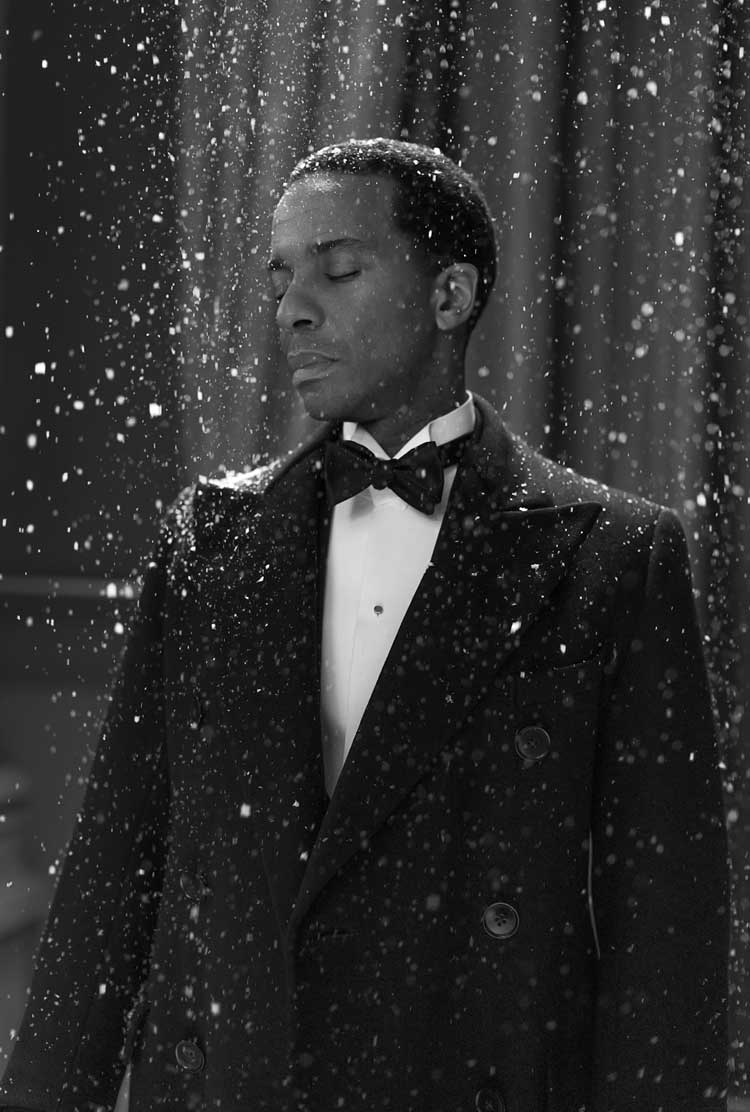

As Once Again nears its end, there is a nocturnal scene of snow gently falling. Locke, formally attired, is standing in it impassively. One of the last lines in the film, spoken by Locke, is credited to bell hooks: “… a culture of infinite possibility is ready to receive us. This is artistic freedom as pure and unsullied as falling snow.” This snow, however, when looking more closely, seems to be falling upwards as if in defiance of gravity and of space and time, as a harbinger, perhaps, of a new future, and new realities. It is not certain, but let us hope so.

[video1]

.jpg)